A review of: Nature and Cities: The Ecological Imperative in Urban Design and Planning by Frederick R. Steiner, George F. Thompson, Armando Carbonell (eds.). 2016. ISBN 9781558443471. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Cambridge, Massachusetts. 465 pages. Buy the book.

Nature and Cities, through the conference and the book, has successfully advanced the urban nature literature—even with the high standards of a McHarg disciple like me!

Little did I know at the time as I was preparing to go to graduate school, in April 1993, a two-day international symposium was held in Tempe, Arizona entitled “Landscape Architecture: Ecology and Design” which brought together an “all-star team” to present on the practice of ecological design and planning in landscape architecture. Four years later, in 1997, the symposium resulted in the publication of Ecological Design and Planning, a volume in the Wiley Series on Sustainable Design. This publication became a seminal publication in the body of literature focused on the role of ecological design and planning in designing and enhancing urban settlements.

Fast forward to 2014, when the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, the School of Architecture at the University of Texas, and George F. Thompson Publishing essentially “brought the band back together” by co-hosting an international conference with the goal to “create a synthesis of new perspectives and projects, evolving models and even theories in landscape architecture and its ever-expanding role in improving urban settings at every human scale” (page xiv). This 2016 book is the proceedings from that event and serves as a de facto “revised edition” to Ecological Planning and Design. The book includes 16 contributed essays from conference presenters as well as an introduction and afterword from the book’s editors.

Given the topic, I knew that McHarg would be front and center in many of the essays. Little did I realize, however, that some of the chapters would become a referendum of sorts on the McHargian philosophy. In Richard Weller’s essay entitled: “The City Is Not an Egg: Western Urbanization in Relation to Changing Conceptions of Nature”, Weller identifies what I would call the “McHargian Paradox”—that is, any attempt to apply a prescriptive method to designing with nature in cities is virtually impossible given the complexity of natural systems, functions, and processes that make aspects of nature “unknowable”: “[McHarg] was showing how development can be adjusted to fit with the basic flows of landscape ecology, but, even so, the theoretical flaw in his thinking remains…Whereas McHarg tried to determine the broad-scale future form of the city predominantly through biophysical data…landscape urbanists embrace the subjectivity of the designer and attempt to integrate a diversity of data across both the sciences and the arts” (p.45). This chapter captures that essence of the ongoing tension between urban spatial planning through geographic information systems and the landscape architecture profession. Here I am, a McHarg disciple, but thanks to my primarily practitioner-based career, I did not realize the fierce debate in the academic world over his legacy.

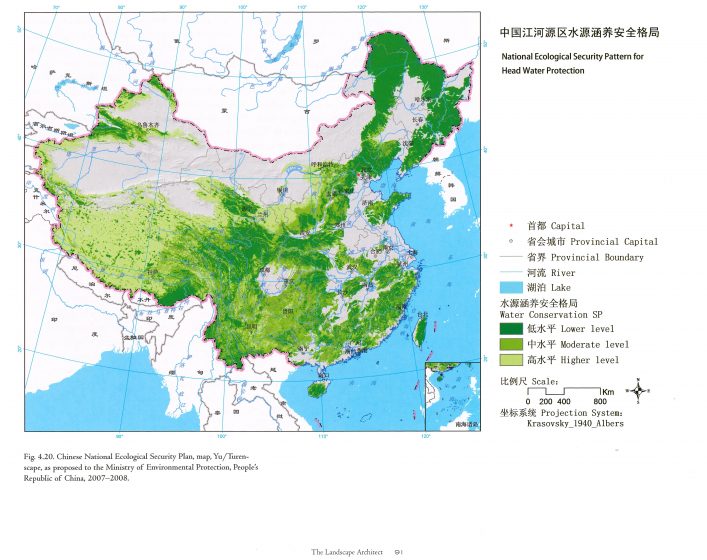

The chronicle of this paradox continues in the essay by Charles Waldheim, entitled “The Landscape Architect as Urbanist of Our Age”. Waldheim observed that McHarg’s branch of “environmentally informed regional planning…came to be perceived, rightly or not, as ultimately anti-urban” and led to “a generation of landscape architects trained as empirical advocates…that was dependent upon a robust welfare state for implementation” (p.71). Waldheim credits the recent renewal of landscape’s relevance for contemporary urbanism not to McHarg but to design culture. I find this one of the most interesting discussions in the entire volume, as it digs deeply into the role of planners and landscape architects to positively impact urban form. I am not able to do the full discussion justice in a short book review. Perhaps with a little touch of irony, however, the example at the end of this chapter on China’s National Ecological Security Pattern looks very McHargian to me.It is perhaps only fitting that the next chapter in the book is from the author of the China work in Waldheim’s chapter—Kongjian Yu—who focuses on “Creating Deep Forms in Urban Nature”. Such forms seem to embrace the best aspects of McHarg’s environmentally informed regional planning and design culture and achieve “human desires within natural processes and patterns”. This “détente” between McHargian planning and design culture continues in the next few chapters, with the McHargian “layer cake” method being acknowledged as a valuable tool to understand a site’s capacity but sustainable landscape design being acknowledged as an essential “systems approach” that leads to creative design solutions. Elizabeth K. Meyer focuses on aesthetics and sustainability that delivers a “manifesto for sustaining beauty”, while José Almiñana and Carol Franklin discuss “creative fitting”, an alternative design practice and theory that attempts to provide a new framework for an “Ecological Aesthetic”.

At about this time in the book, the tone starts to shift away from being a referendum on McHarg to more of an emphasis on defining and developing an operational framework for the concept of resiliency. Intellectually, this is one of the best contributions of this publication. The word resilience gets thrown around a lot in planning circles these days, and the authors tackle this subject very effectively from their unique perspectives. Meyer, for instance, points out that resilience, adaptation and disturbance are becoming operative words in ecosystem studies. Almiñana and Carol Franklin list resilience, biophilia, and regenerative design as three key elements of a new alternative design practice and theory.

The focus on resilience continues in Forster Ndubisi’s chapter entitled: “Adaptation and Regeneration: A Pathway to New Urban Places”. In this chapter fundamentals of resilience theory—the adaptive cycle of ecological systems—are first introduced in detail: growth, consolidation, collapse, and renewal. This leads to a commonly accepted definition of resilience from Pickett et al, 2004[i], which is “the ability of a landscape to absorb change or disturbance, without modifying its underlying structure and functionality or transforming it into a new state” (p.197). Ndubisi lays out seven aspirational yet pragmatic concepts for spatial planning and design and principles for creating and maintaining resilient and regenerative urban landscapes: (1) designing for change and uncertainty, (2) conservation of ecosystem services, (3) adapting and mitigating impacts of climate change, (4) embracing regeneration, (5) affirming regional thinking and action, (6) collaborative processes, practices, and learning, and (7) maintaining places.

Most of the remaining chapters in the book address strategies for implementing these best practices for creating resilient and regenerative urban landscapes. Susannah Drake offers an infrastructure-based approach—a Works Progress Administration 2.0—in which green and gray infrastructure work together to create a “new natural infrastructure system”. As a planner who has practiced green infrastructure planning at multiple scales over the past 20 years, this philosophy resonated with me, and Drake provides some excellent implementation examples from her work, including the Gowanus Canal Sponge Park and the Highway Overpass Landscape Detention (HOLD) System to collect and filter stormwater from highway downspouts. Tim Beatley points out that 40 percent of the world’s population lives within 40 miles of a coastline, so he discusses biophilic cities and strategic elements of “blue urbanism” that would certainly support regional thinking and action in urban coastal cities if his recommendations were implemented.

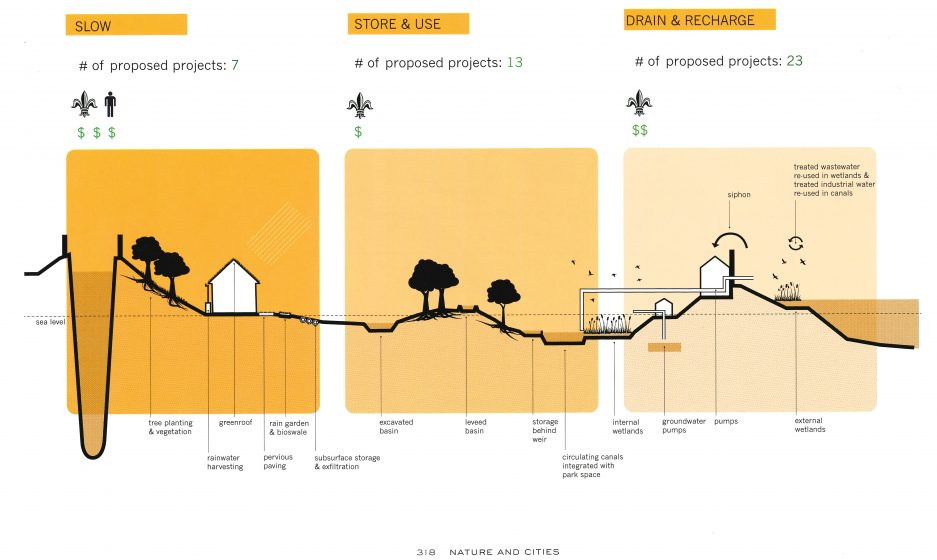

Nina-Marie E. Lister digs deep into implementation with “Resilience Beyond Rhetoric in Urban Landscape Planning and Design”. She provides cross-section diagrams developed by University of Toronto Landscape Studio students that demonstrate resilience opportunities in the Greater New Orleans Water Plan and Toronto’s Wet Weather Flow Master Plan (pages 318-319). Laurie Olin’s essay on “Water, Urban Nature, and the Art of Landscape Design” showcases best practice examples from Philadelphia, Cleveland, New York, and New Jersey where water is a central design aspect that positively promotes urban nature.

As I reached the end of the book, I began to ponder whether the co-editors’ achieved their goal: to create a new synthesis of ideas. My first thought was that it did achieve an objective that Ignacio Bunster-Ossa points out in the back cover quote: that ecology is at the center of an urban future and provides “a systemic way of thinking toward building a healthy and resilient future”. But after absorbing so much information from 16 nationally acclaimed experts on urban nature, I still felt some of the frustrations that were identified by Anne Whiston Spirn way back in Chapter 3, in “The Granite Garden: Where Do We Stand Today?” Spirn argues there is a “crisis of comprehension and synthesis” in research on cities and nature: “edited volumes…are valuable, but they are not comprehensive and they do not offer a synthesis”. Her solution is a combination of literature reviews, teams to review the state of research, and clearinghouses that provide models of practice. I absolutely agree, but in order to do effective “meta-analysis” of these important urban nature concepts, there needs to be first-class applied research and publications and high-quality forums to share the work. Nature and Cities: The Ecological Imperative in Urban Design and Planning, through the conference and the book, has successfully advanced the urban nature literature—even with the high standards of a McHarg disciple like me!

Will Allen

Chapel Hill

[i] Pickett, Steward, Mary Candenasso, and J. Morgan Grove, “Resilient Cities: Meaning, Models, and Metaphors for Integrating the Ecological Socio-Economic, and Planning Realms,” Landscape and Urban Planning, Vol. 69, No. 4 (October 2004): 369-84.

To buy the book, click on the image below. Part of the proceeds return to TNOC.

Leave a Reply