The city landscape, because of the holistic nature of city-forming factors and urban community, is like a book in which the various characteristics of the city and its citizens are visible: values and norms, economic conditions, tastes and aesthetic criteria, commitment to the living environment, and so on. Throughout history, the city, as a dynamic system, is a result of the interaction between city-forming factors and the urban community. It has a powerful and significant impact on the cultural, economic, aesthetic aspects of its citizens’ lifestyle.

This article addresses the human interventions in the selection of plant species in green spaces of Tehran, and the cultural, social and lifestyle roots of these interventions.

Plant selection models and abundance of non-native species in Tehran’s green areas

Today, Tehran is in critical condition ecologically. Tehran’s water sources are alarmingly declining. The effects of global warming are clearly visible on weather conditions, rainfall and the annual maximum and minimum temperatures of the city. The problems of air pollution and groundwater pollution are growing. In this situation, thoughtful design based on a set of ecological values is key. Unfortunately, what is going on is the complete opposite.

Plants are an important and effective element for environmental designers and landscape architects to create one of the most important soft parts of the landscapes—the greenery. Although it may be appealing to be innovative in design and in the choice of materials and tools, to create a new atmosphere and the perception of a unique space it is prudent to be cautious. When plants play the key role of the in creating a new space, decisions about the other design features should be made rationally. There must be considerations beyond the morphological expression and aesthetic features such as texture and color, and the visual and sensual attraction that they can add to space. Ecologically, botanically, and biochemically they have a specific quality which must be elevated above any other design element.

The invasion of exotic and non-native plant species into urban areas and private gardens is the result of neglecting these very important ecological aspects of plants. This can lead to the extinction of native species and a disturbance in the ecological balance of the floristic community of an area. “Today, many native wildlife and plant species struggle to compete with exotic, invasive horticultural and anthropogenically related non-native species for survival. Aggressive species with no natural predators are, in many areas, replacing native plants and animals at an alarming rate.” (Kevin Songer, TNOC Roundtable, August 12, 2015).

For more than two decades, the use of exotic and non-native plant species which are not ecologically adapted to the climate in Tehran has resulted in high maintenance costs. The expense is the result of the lack of effort among designers to create innovative aesthetic combinations of native species.

Recently, in many of the world’s most important and beautiful cities, such as London or New York, planting designers have been choosing native species with low input maintenance, and that are climatically and ecologically adapted to the region. Researchers such as Professor Nigel Dunnett and designers such as Piet Oudolf and many others have been successful in this regard. The spaces they have created are very impressive, soulful, aesthetically eye-catching, biodiverse and sustainable, and in harmony with the ecosystem. The methods of meadow-like, low input planting, the reuse of forgotten, resident species in creative combinations, and the simultaneous screening out of invasive species are important achievements of these designs. All of these efforts are being made because of the growing demand for more sustainable development, especially in cities like Tehran, with severe climatic conditions and limited natural resources.

If the use of non-native exotic plants, especially water-loving species, with high-cost maintenance, is a concern in a city like London, it is ecologically critical in Tehran. The use of creative combinations of native and resident plants is more necessary in Tehran than London.

Grass in Tehran urban green areas

Grass in Tehran urban green areas

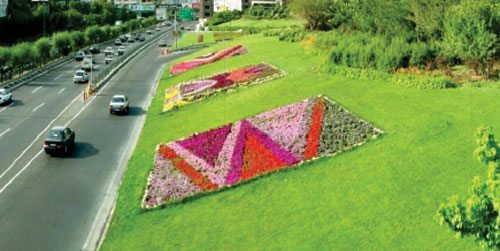

Currently, grass is one of the main plantings in public and private green areas in Tehran. Despite the various municipal and environmental organizations’ declarations to prohibit the use of this plant, it is still used because of the rapid growth and rapid greening of flat lands, in vast areas like highway corridors, neighborhoods, and extended flat areas in city parks. The most important reason for using grass as a ground cover in cities with adapted climates is its ability to tolerate trampling and providing a leisure space for citizens.

In Tehran, there are many spaces such as highway corridors that are not accessible by citizens and pedestrians, which are covered by grass. Why? In parks and green spaces, areas that ought to be accessible to pedestrians, citizen access is limited due to the severe vulnerability of this grass in the semi-arid climate. Entrance barrier signs are installed in the lawn, preventing people from using parks and green spaces as they are intended. In both of these situations, the use of grass as ground cover seems ridiculous.

The very shallow depth of the grass roots, in comparison to the other meadow-like and ground cover species, increases the need for irrigation several times in semi-arid climates like Tehran, due to high evaporation and rapid outflow of water from the grass root. The reliance on grass as a ground cover, whether in highway corridors or parks imposes significant damage to water resources, the ecosystem and the economy of the city, and yet most important feature of this plant—its ability to withstand foot traffic—is not used.

In such a situation, the use of native meadow-like species seems a very good idea. Some of them, such as Taraxacum officinale (dandelion), red Kan poppy (Kan is a green lush mountainous region in the west neighborhood of Tehran), Achillea millefolium (yarrow), Berberis thunbergii, Origanum vulgare, Mentha pulegium, Ferula gummosa and other species can be used to create aesthetically eye catching ecological mixes. Drought resistant species such as Sedum are another solution. As is a species of the perennial herb Frankenia salina that is native to the desert regions of Iran, beautiful in different seasons, and is very tolerant of severe climates.

Use of evergreen non-native exotic species in Tehran

Living organisms and biodiversity have naturally reached a degree of equilibrium and adaptation so that in some cases small inappropriate changes may cause great stresses in a region. The plant community diversity and floristic composition of Tehran is no exception to this general principle. The invasion of non-native exotic species has caused many ecological problems in recent years and has been costly in terms of natural and economic resources, such as reduced groundwater levels, and losses of soil quality from both macro and micro features.

For example, the excessive planting of inappropriate and non-native varieties of cedar and pine species has led to a change in the nutrients and acidity of the soil, which has led to the disappearance of many native species such as Platanus and Populus. The problem of water and air pollution are the main reasons for increased use of some non-native species such as Arizona cypress (Cupressus arizonica ) and other needle-leaved evergreens in recent decades.

In addition to their ability to withstand pollution, evergreens, due to their novelty in shape and aesthetic aspects, are very popular with people and plant designers in private and medium-scale public green areas. And so, at a very high rate of speed, these non-native, ecologically incompatible and climatologically inappropriate species made their way into construction areas and now fill the city’s public and private green space. Acer palmatum, Buxus semperviren, Cycas, Thuja occidentalis, Chamaecyparis lawsoniana, Myrtus communis, Juniperus excelsa and others are found in Tehran’s public and private green spaces. And annually, hundreds of such species disappear because of winter and summer drying. Vast sums of money are spent on the costly purchase and maintenance of these plants, which in many cases are not long-lasting.

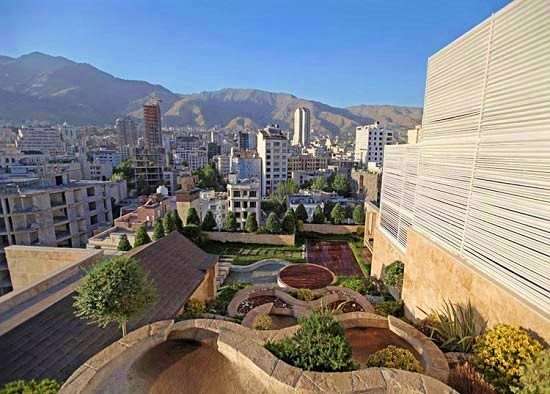

Tehran has been a city under construction for many years. In any part of the city if you stand on the roof, with a 360° degree view, five or more tower cranes, are visible. This permanent state of construction, with the its associated damage to the resident trees during the construction process, has destroyed the precious, and original native green areas of the city.

On the other hand, because of the heavy cash fines the municipality receives from owners due to the loss of the original trees, there is no incentive to re-plant. If the new tree dies, the owner will be subject to yet another heavy fine. Perhaps a better solution for municipal associations would be to require project owners, in lieu of cash fines, to plant native and high-tolerance trees in urban areas and city green belts in large numbers.

The prevalence of planting styles related to humanism

In some periods of the world’s garden design history, due to the historical and social conditions of that era, the designers used the plants in a very formal and pruned way. They created harmony with symmetrical plans, and were in keeping with the humanistic values of the time. The art of topiary, rooted in ancient Greek gardens, once again climbed into to the green spaces. The garden was arranged in a logical way and was filled with manmade features meant to display the power of humans over nature and the whole of the universe, and to maximize enjoyment for the landowner. The glory of this style is seen in the Italian Renaissance garden.

Contrary to this trend, one of the most important features of Iranian traditional gardens is naturalism, and avoidance of non-practical decorations and non-productive plant species. Optimization and the use of indigenous materials is one of the main features of Iranian architecture and gardening. No species in the traditional Persian garden was planted solely for decorative purposes. Water was used as a very valuable element, with great caution and skill, throughout the garden for both dramatic and irrigation purposes. In traditional Persian-style gardens, nature is the dominant element due to cultural beliefs and climate demands.

Nature as a bracing and divine element has always been a special interest of Iranians rooted in both religious belief and life-style. Green areas were greatly valued in this semi-arid land. The courtyard (Hayaat), the site for planting trees and placing the Persian traditional water pond (houz), is the most important part of the traditional Iranian house plan. All parts of the house are visually and locationally arranged around it and based on its axes. The tradition has always been to plant native species with the highest tolerance and lowest maintenance. When studying historic examples of traditional houses in Iran, from north to south, you can see the climate adapted changes in plant choice.

With such a historic and cultural background, the current trend in creating planting designs for Tehran landscaping projects is to be more contemplative and strange.

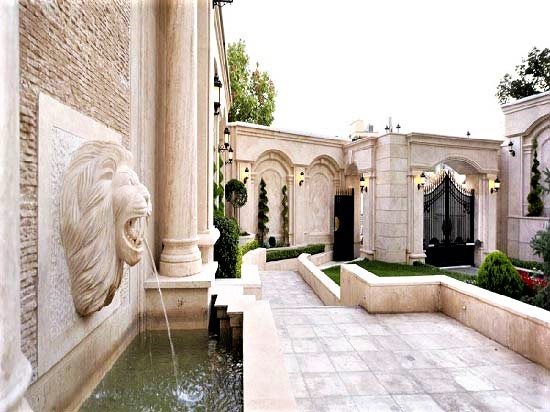

It seems that the new trends ignore the traditional patterns and achievements in general. Not of course in the direction of improving natural environment and quality of life for citizens, but only for the purpose of demonstrating luxuries and inappropriate temporary modes. For many years, the overwhelming influx of imported, non-traditional, and eclectic architecture style has changed the face of Tehran into a combination of super-luxe neo classic style informed by Arabian taste.

However, in recent years, many efforts have been made by contemporary architects and municipality organizations to reduce and correct this trend with greater emphasis on indigenous materials and prototypes of Iranian traditional architecture. Unfortunately, tastes of investors, builders and owners still trend toward super-luxe and costly architectural styles from beyond the region.

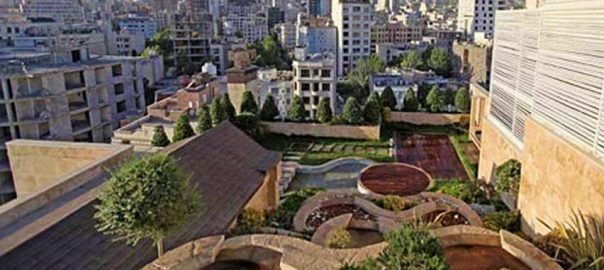

Lands that were once covered with native mature trees, are converted into “luxury” buildings with low-depth planters filled with exotic non-native species, small green areas and decorative roof gardens which with the slightest neglect of the gardener, or sudden changes in the weather during winter or the hot drought days of summer could be lost. Suddenly, these “luxurious” buildings with their decorative “green” spaces, in both public and private areas, will not be appealing to buyers.

This trend has already been exported to other major cities in Iran. Not only private spaces, but also small-scale urban areas have been affected. The use of resident native species of Tehran such as Nerium oleander, Syringa vulgiris, Chimonanthus, Alcea, Forsythia, Cercis canadensis, Spiraea vanhouttei, Fraxinus excelsior, Ulmus, Platanus and others are almost obsolete. The planting style that fits the luxury, neo-classical architecture has become widespread. Inexpensive native plants are not used due to the lack of attractiveness for buyers of these properties, and formal and sculptural looking plants are so popular, that only the most apparent characteristics of species are considered. Plant nurseries are also reluctant to produce better samples of native species, preferring exotic imported ones with high sales profits.

The “green” roofs associated with this neo-classical construction has also become an epidemic luxury element. These roofs are for appearance only, having nothing at all to do with the ecological goals of creating a green roof. Elements such as a roof top swimming pool, water features, antique pots and expensive stone sculptures and other decorative elements are the featured elements of these green roofs. The plants are just decorative, contributing no more than the hardscape.

In summary, both the public’s taste, and prevailing popular cultural trends on how to design and create urban and private constructed environments has had a damaging direct impact on Tehran’s ecosystem, floristic composition and diversity. It has led to the vanishing of native species and changed the greenscape of the city as a whole. The visual impact of these changes on the landscape, and the tendency for Iranian middle-class culture to follow the predominant style, unfortunately means that these anthropogenic interventions and their after-effects will continue to increase over time.

Maryam Akbarian

Tehran

Add a Comment

Join our conversation