Beginning operation in 1977, the 885 megawatt facility was named for New York’s 46th Governor Charles Poletti. If there is anything in a name, the Poletti facility had an auspicious one. Charles Poletti graduated from Harvard Law School, served on the New York State Supreme Court, and been elected New York’s Lieutenant Governor alongside Governor Herbert H. Lehman. Poletti had the distinction of being the first Italian-American governor in the United States (albeit serving only 29 days to complete Lehman’s term after Lehman joined the World War II effort). During World War II, Lieutenant-Colonel Poletti was in charge of restoring essential public services in occupied Italy. After the war, New York Governor Averell Harrimann appointed Poletti to the New York State Power Authority. So, when the Astoria generating facility was named in his honor, it had a lot to live up to. Sadly, the facility was far less impressive than its namesake. Indeed, by the time Charles Poletti died in 2002, New York Power Authority was mired in litigation with angry neighbors bent on shutting the dirty, polluting facility.

Beginning operation in 1977, the 885 megawatt facility was named for New York’s 46th Governor Charles Poletti. If there is anything in a name, the Poletti facility had an auspicious one. Charles Poletti graduated from Harvard Law School, served on the New York State Supreme Court, and been elected New York’s Lieutenant Governor alongside Governor Herbert H. Lehman. Poletti had the distinction of being the first Italian-American governor in the United States (albeit serving only 29 days to complete Lehman’s term after Lehman joined the World War II effort). During World War II, Lieutenant-Colonel Poletti was in charge of restoring essential public services in occupied Italy. After the war, New York Governor Averell Harrimann appointed Poletti to the New York State Power Authority. So, when the Astoria generating facility was named in his honor, it had a lot to live up to. Sadly, the facility was far less impressive than its namesake. Indeed, by the time Charles Poletti died in 2002, New York Power Authority was mired in litigation with angry neighbors bent on shutting the dirty, polluting facility.

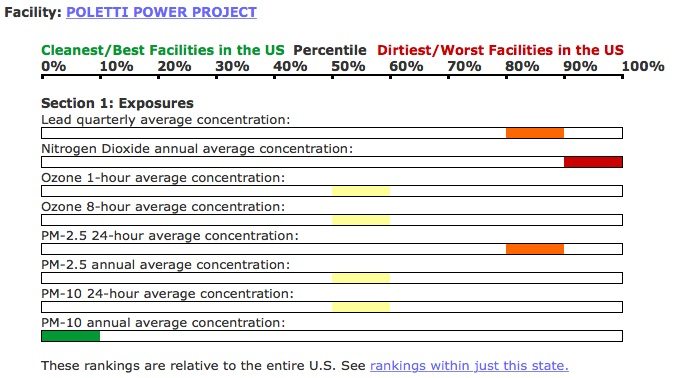

The Poletti plant served the state and local government; generating electricity to run schools, public hospitals, government offices and New York’s extensive subway and electric commuter train system. However, the toll it imposed on the surrounding community of Astoria was immense. The Poletti Plant ranked among the dirtiest plants in the United States.

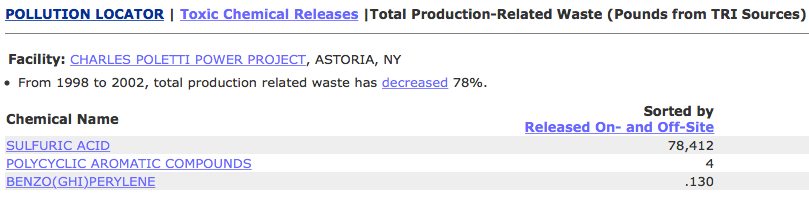

In 2002, the year NYPA agreed to shutter the facility, the Poletti emitted more than 78,000 pounds of sulfuric acid, and that was a 78% decrease from 1998 when the plant emitted more than 358,000 pounds of pollutants.

That year, the Poletti also released 38 tons of small particulates (PM2.5), 44 tons of larger particulates (PM10) 1311 tons of sufur dioxide, 78 tons of volatile organic compounds, and over 2000 tons of nitrous oxides.

Despite this immense pollution load, New York Power Authority proposed to add a new 500 MW facility alongside the Poletti plant. Astoria was already home to 60% of New York City’s generating capacity and the local community objected to an additional polluting facility in their neighborhood. Their legal strategy was innovative, involving a coalition between Natural Resouces Defense Council, a national environmental group, New York Public Interest Research Group, a New York environmental group, and a community NGO called the Coalition Helping Organize a Kleaner Environment (CHOKE). Joining with local politicians, and public housing leaders, the coalition intervened in the administrative permitting process and challenged the issuance of a “certificate of environmental compatibility and public need”—a legal prerequisite for the new facility. The coalition argued that the community was already overburdened, and that the additional particulate pollution from the new, albeit cleaner facility would jeopardize public health and environmental safety.

While that proceeding was ongoing, another environmental justice group was attacking New York Power Authority from a different angle. In 2001, the Power Authority announced plans to install eleven additional natural gas turbine units around New York City. This plan was nominally in response to the rolling blackouts that California had suffered that summer (which were later revealed to have been caused by Enron’s market manipulations, not an actual shortage of generating capacity). Each of the proposed new units could generate 44 MW of power, and the majority of the units were to be placed in pairs at multiple sites around New York City. Thus, the paired units could together generate 88MW of power. Under New York Law at the time, any facility capable of generating 80 MW or more was deemed a “major generating facility”, a label that triggered a host of public hearings and certification requirements (called an Article X application). However, the Power Authority obtained an exception by promising that each pair would be configured to generate only 79.9 MW of electricity—just below the 80 MW threshold.

The Power Authority then concluded that there would be no negative environmental impacts from this project, and that the cumulative impacts of the proposed eleven turbines would be insignificant.

UPROSE, an environmental justice group, sued, alleging that NYPA failed to adequately consider the environmental impacts of the plan. Although UPROSE lost at the trial level, the appellate court overturned the decision, and found that there were potential environmental impacts sufficient to require an environmental impact statement. In particular, the court required NYPA to assess the impacts from PM2.5—small particulate pollution that can cause or worsen respiratory and cardiovascular disease.

The anti-Poletti coalition used the UPROSE decision to its advantage, persuading regulators to order a hearing on particulate matter associated with the Astoria facility. This administrative ruling gave the coalition leverage that they used to strike a deal. In exchange for a withdrawal of coalition objections to the new 50 MW plant, the Power Authority committed to a six to eight year timetable for shutting down the dirty Poletti Plant, converting to the cleanest fuel available, investing in the community, and reducing the Poletti’s operation during the interim. So, the dirtiest plant in New York City was replaced with a facility reputed to be “one of America’s cleanest”. Perhaps learning from poor Poletti’s tarnished name, the replacement facility was simply called Astoria I.

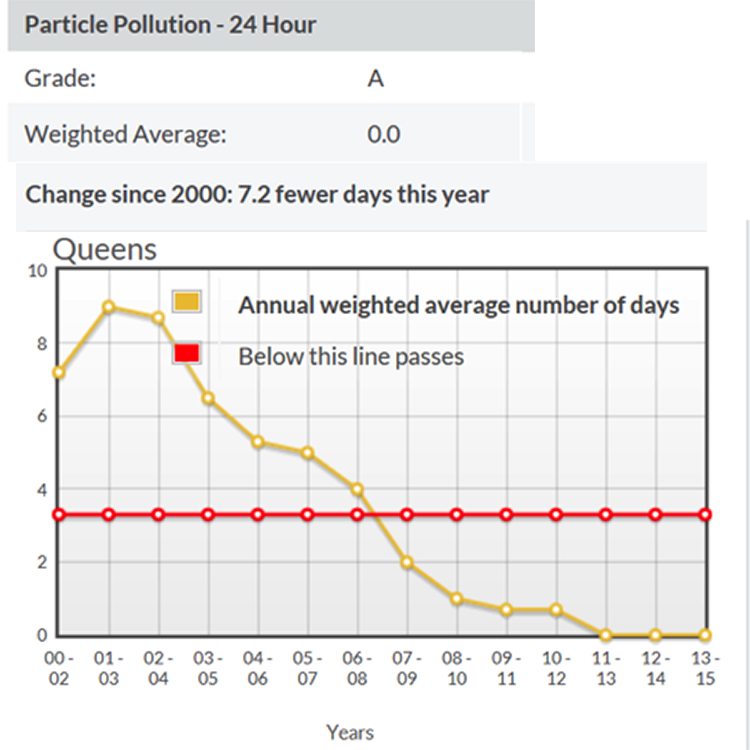

In the years since Poletti shut down, the air quality in Astoria has improved markedly. Particulate pollutants have plummeted.

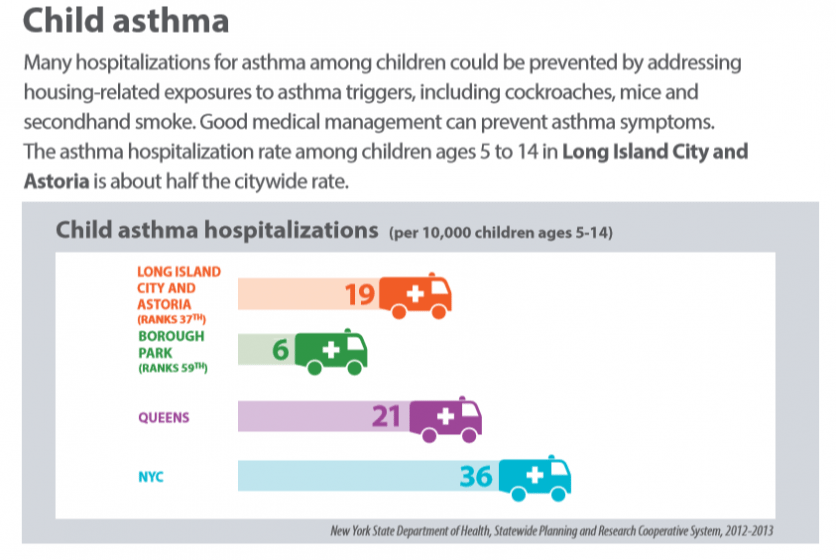

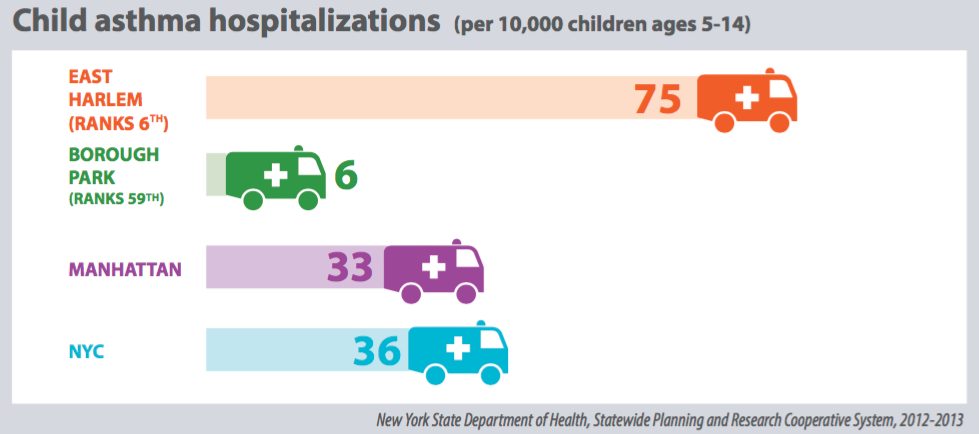

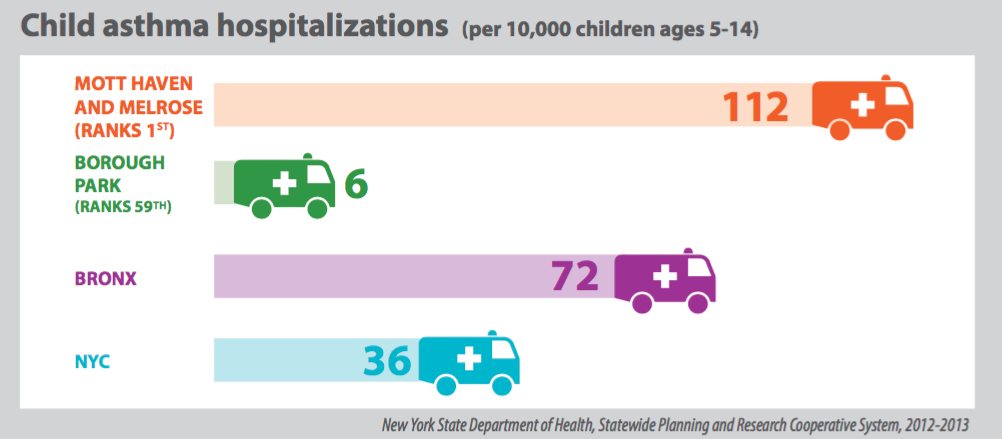

Asthma hospitalizations are down well below the average for New York City.

A cleaner environment has taken a toll on the community in a different way. Gentrification is rife, with property values increasing 75% in the years since the Poletti Plant was shuttered. Long-time residents are beginning to find themselves priced out of the neighborhood they fought to improve.

The saga for shutting down Poletti served as inspiration for Bina’s Plant, Book 2 of the Environmental Justice Chronicles soon to be released by the Center for Urban Environmental Reform.

I wish I had a brick from the Poletti. I would display it in my office as both a celebration and a reminder. Environmental justice victories are rare enough that they need to be savored, but it is vital that the benefits of those victories redound to all citizens, and that those who achieve those victories are not pushed out of their neighborhoods.

So what lessons does shutting down the Poletti offer for other similar campaigns? First, collaboration is key—local groups must lead the way, but they need resources and support from state-wide and national groups. Second, it helps when local politicians are fully on board. With the campaign to shut Poletti, elected officials joined the lawsuits, and used the platform of their office to advocate for environmental protection.

That sounds so simple. Yet, too often, institutionalized racism is a barrier to achieving the kind of cooperation that was so successful in the Poletti campaign. De facto segregation and racialized voting can leave poor and minority communities isolated in their battle against pollution in their neighborhoods. Air quality in those communities can stagnate or even decrease, even as rest of the city improves. For example, even though New York City now has the cleanest air since monitoring began, asthma rates are still unacceptably high in parts of the Bronx and Manhattan, with black and Latino/a children hardest hit.

We can and must do better. To truly learn the lessons from shutting down the Poletti, we must confront environmental injustice and replace isolation with community. Among other things, that means electing politicians committed to social justice. National environmental groups must also do their part to confront their past disengagement with issues environmental justice. Fortunately, this kind of rethinking is already starting to happen.

Rebecca Bratspies

New York

Add a Comment

Join our conversation