A review of “Palm House”, a commissioned project on view at the Edinburgh Art Festival until 27 August 2017.

In the late 19th century, Geddes proposed an interconnected network of small green spaces, acting as the ‘green lungs’ of Edinburgh’s cramped medieval-era Old Town. Many of these so-called ‘pocket parks’ continue to be used today.

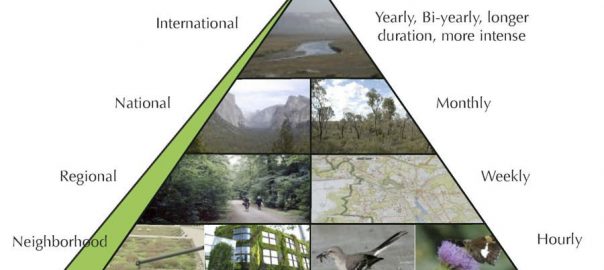

Cue Patrick Geddes, a Scottish polymath who had recently taken on a lectureship in Zoology at Edinburgh University. During these last two decades of the 19th century, Geddes would address the challenge of revitalizing Edinburgh’s infamous slums. This would set the foundations for his most seminal works in city planning, from pocket parks to early bioregionalism, which had profound influence on our sense of ecology in urban planning, and on later thinkers such as Lewis Mumford.

Rather than employing a drastic redevelopment scheme of razing the old buildings to make way for new, Geddes proposed small changes for the Old Town through a “Conservative Surgery” method. Geddes believed that this method of redevelopment would allow the Old Town to retain its character, while also improving living conditions for the area’s residents. One of the key strategies in enhancing liveability for the city’s poor was the introduction of public green spaces within the dense fabric of tenement buildings. The lack of space in the over-crowded Old Town did not hinder Geddes’ vision; the planner proposed an interconnected network of small green spaces, as this configuration would be more accessible and feasible. Acting as the “green lungs” of the city, many of these so-called “pocket parks” continue to be used today.

Johnston Terrace Wildlife Reserve is just one of Geddes’ former gardens; run by the Scottish Wildlife Trust, it is also Scotland’s smallest wildlife reserve. Nestled into a hillside in the shadows of an unyielding castle, the garden is easy to miss. The space is accessed from the steps of Castle Wynd, a busy pedestrian corridor for the millions of tourists that visit Edinburgh each year. A raised boardwalk path takes visitors through a meadow drift; paths converge at a cleared gathering space towards the rear of the site.

While the gate to the garden remains locked to the general public for most of the year, Johnston Terrace Wildlife Reserve can be visited this August during the 2017 Edinburgh Art Festival. The festival, which runs from 27 July- 27 August, features a collection of four new commissions which celebrate the centenary of Patrick Geddes’ forward-thinking work, The Making of the Future: A Manifesto and Project (1917). One of these commissions, artist Bobby Niven’s “Palm House”, resides within and responds to the context of the Johnston Terrace Wildlife Reserve.

“Palm House” is envisioned as a social sculpture, a space for the exchange of ideas and community gathering. The structure provides shelter from the elements during Edinburgh’s particularly wet month of August, but the work does not turn its back on the open-air context in which it is sited. Constructed with green oak timber framing and transparent acrylic siding, the small hut closely resembles a glasshouse, a clear artifact from the artist’s research into the glasshouses used to cultivate palm trees at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Edinburgh. The line between indoor and outdoor is blurred, due not only to the construction materials utilized but also the abundant collection of potted plants within the shelter. Sculptural elements of the structure include wooden hand-shaped supports, a recurring symbol throughout Niven’s work. The double meaning of the work’s title, “Palm House”, references both the concept of the structure as a glasshouse (i.e. a palm tree house), but also the symbolic motif of these hands.

“Palm House” will also accommodate a series of four week-long artist residences across the month of August. The artists selected for the residencies (Neil Bickerton, Alison Scott, Daisy Lafarge, and Deirdre Nelson) will have the opportunity to produce works in this ‘off-grid’ urban oasis. The intention of holding these residencies in-situ is to gather a collection of ideas and responses to the histories and environment of the site, with the structure acting as a space for growth of both plants and creative practice.

As a project, “Palm House” responds to the ecological and seasonal nature of its surrounding; the work will always be changing and evolving through the month of August, creating its own ecology of collaborative production and exchange of ideas. Within the first few days of opening, the project has already proven to be a popular refuge amid busy festival hubs and corridors. Many visitors happen across the site by chance, and the experience of both the garden and the work has been a pleasant surprise for many.

Whereas other exhibitions in the festival—and in the field of contemporary art in general—may make the visitor feel like there is an underlying message or a concept to “get” in order to truly understand the work, this project simply allows viewers to enjoy being within a space and place, and to allow their own experience to take precedence over any preconceived notion of what the work “is”.

In his pamphlet, The Making of the Future, Geddes envisioned a re-construction, re-education, and renewal of society. He advocated for a post-war society where civic life is improved in a combined interdisciplinary effort of “Art and Industry, Education and Health, Morals and Business”. These ideas of interdisciplinarity and civic participation are activated in Niven’s work, which appeals to visitors of many backgrounds and perspectives. In the instance of Palm House, the combined experience of art and nature has the powerful effect of making people stop, observe, immerse themselves, and react to something previously unnoticed.

More broadly, employing Geddes’ vision from The Making of the Future: A Manifesto and Project as a curatorial concept has bold implications. In the age of international art fairs and biennials acting as a reigning force in the contemporary art world, selecting this theme for the 2017 Edinburgh Art Festival commissions suggests an antithesis to the loud and commercialized aspects of such events. This theme, and the commissioned works that it has evoked, insinuate a worldview that leans towards anti-capitalism rather than profit, and a democratization of art rather than self-referential exclusivity.

The theme also provokes a sense of localization above globalization during a festival season that could easily be criticized for being insensitive to its context and the heritage of Edinburgh. In the month of August, multiple festivals put on thousands of shows, exhibitions, and events in Edinburgh; an ephemeral whirlwind of performers and nearly 3 million visitors from across the world gather in the UNESCO-designated World Heritage Site. The Edinburgh Art Festival’s commission concept is specific, celebrating context and locality in a way not frequently seen during Edinburgh’s festivals.

Though the choice of theme for the Edinburgh Art Festival may not seem like an immediate association for a series of contemporary art works, the fruition of projects like Palm House prove that the theories championed by Geddes maintain their cultural relevance today.

In a world of mass media and internet virality it can be quite easy to think globally.

But it takes intention and subtle confidence to act locally.

Allison Palenske

Edinburgh

Leave a Reply