The spectre of “gentrifying conservationism” and “green evictions” will increasingly haunt segregated spaces and poor communities worldwide.

From a socially critical viewpoint, environmental protection remains a dangerously vague expression, as long as the questions regarding which environment should be protected, how and for the benefit of whom are not adequately clarified. There are some socially very conservative approaches to environmental protection (represented by a heterogeneous set of statements and mottos such as “humans are nothing, nature is everything”, “environmental protection is ultimately a matter of national security” and “the free market and property rights provide the best means to protect our environment”), and among them we can find an interesting type, which I have termed “gentrifying conservationism” (Souza, 2016a, 2016b). It corresponds to a truly exclusionary kind of environmental protection.

The term “gentrification” was introduced in the mid-1960s, but the concept has become widely used only in recent decades as a result of the new waves of “urban renewal” plus displacement of poor people that we have witnessed in the context of the post-1980s (or post-1990s in some countries) neo-liberal city. Although processes of urban renewal that result in displacement of poor people have occurred for generations in many cities, as European and American (both US-American and Latin American) examples testify, gentrification as a concept tries to capture the new aspects of contemporary globalised and neo-liberal capitalism. Different aspects of gentrification have been systematically studied since the 1980s, and several authors have discussed the socio-geographical range of this phenomenon. One of the facets that we must pay attention to is the interplay between gentrification and environmental protection.

An increasing number of authors have paid attention to this interplay. Contributing to a debate in The Nature of Cities (TNOC) a few years ago around the question “What are the social justice implications of urban ecology, and how can we make sure that ‘green cities’ are not synonymous with ‘gentrified’ or ‘exclusive’ cities?,” Rebecca Bratspies warned that “without strong public-minded government oversight, ‘green’ development too often leads to exclusion and displacement” (TNOC, 2014). However, she and most other contributors seem to be too optimistic regarding the potentialities of state-led urban design and planning, overemphasising the effectiveness of tools such as inclusionary zoning. They fail to recognise both the deeper causes of gentrification and displacement (that is, the capitalist city, particularly the neo-liberal one) and the essential limits of state-led urban planning.

In the Global North, a strong link between gentrification and the designation of conservation areas has been emphasised by authors as different as, for instance, Ahlfeldt et al. (2013) and Sandberg et al. (2013). Ahlfeldt et al. (2013) do not address it from a particularly critical point of view; instead, they stress the importance of “cooperative behaviour” between homeowners and the market, observing that most buyers acknowledge and appreciate increases to their property’s value when nearby areas are designated as conservation zones. In contrast, Sandberg et al. (2013, p. 238) explore what they understand to be a “neoliberalisation of conservation” through critical lenses. For them, the exurbanites they observed in the Greater Toronto area—specifically, in the place known as Oak Ridges Moraine—“[…] leave the city in search of the ‘ideal countryside’ based on an Anglo-American countryside idea, hoping to become more closely connected to nature” (p. 110). But what Sandberg et al. actually found there was, in their words, “[…] an attempt by middle-class property interests to use the rhetoric of environmentalism to protect and further their own amenity and landscape consumption values” (p. 20). While “[e]xurbia epitomizes an individualized, private, and exclusive living in an idealized nature” (p. 20), the development industry, for its part:

has […] used the Oak Ridges Moraine brand to market housing developments. […] This aesthetic is seen in the numerous subdivisions that are named after the very same ecosystems that they have replaced. […] Ravine lots, creek lots, or lots next to woods are marketed as a premium. Housing developments are portrayed as green communities that constitute privileged opportunities to live in harmony with nature.—Sandberg et al. (2013, p. 223)

The word that seems to summarise the process—gentrification—is used only at the very end of the book (see Sandberg et al., 2013, p. 241), but the authors make it clear that they understand very well the elitist character of such a process. Indeed, the area has become “the exclusive preserve of the wealthy” (p. 241). In fact, as they say, “[o]n the Oak Ridges Moraine, combined growth and nature conservation plans promote […] an exclusive landscape defined by environmental values that accommodate residents of financial means […]” (p. 232–233).

This is an example of what I call “gentrifying conservationism”, or conservation actions that, by their very design, tend to produce gentrification. Interestingly, as this example also shows, conservationism itself is under such circumstances more often than not very limited: “[t]he current dominant policies in Ontario to preserve nature and promote growth share a common nature aesthetic that is essentially used to protect both development and nature, but in the end the system serves to maintain exclusive residential and industrial property values while excluding other interests and compromising nature in inadvertent ways” (p. 233; emphasis added), in the sense that the conservation outcomes produced in these circumstances are often very limited or even absent, by virtue of new threats. Perhaps unsurprisingly, what seemed to be the primary goal was probably little more than a convenient excuse for real estate and capitalist interests.

Business interests can very much refine and expand the strategies used to achieve capital accumulation, and this sort of “conservationism” is one of them. As Sandberg et al. (2013) put it, Oak Ridge Moraine’s story is about “the pervasiveness and mutability of the prevailing growth paradigm and the way it is not superseded but embedded in new ways of thinking about—and even selling—nature on the Moraine” (p. 235). Within this framework, an interesting alliance emerged: “[w]e documented a sustained campaign that moved beyond place-based activism to form networked coalition of rural and urban interests, homeowners, and environmentalists who organized on a regional scale and drew upon a wider anti-sprawl and environmentalist network” (p. 235).

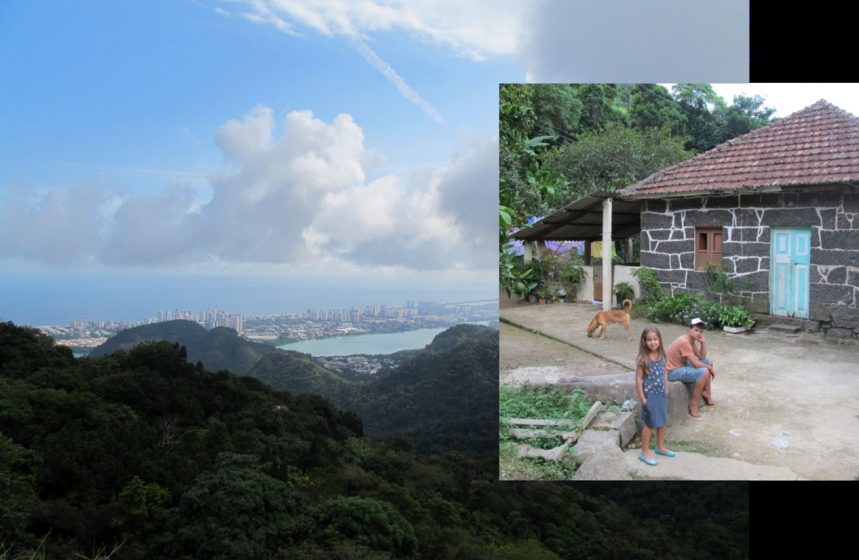

The reality that inspired me to suggest the expression “gentrifying conservationism” some time ago was in Rio de Janeiro, more specifically the tensions that have taken place in the buffer zone of the Tijuca National Park. In Rio’s case, it was a complicated alliance of groups from different movements—pro-environment, pro-growth, anti-poverty—that were different in detail from the Canadian situation studied by Sandberg et al., but with an essentially similar meaning.

In Rio de Janeiro, the pro-environment and at the same time clearly anti-popular alliance has been especially developed in last decade. Located right in the heart of the city, the slopes of the Tijuca massif influence the landscape of many neighborhoods of the city—ranging from the privileged areas of the South Zone to many favelas. Of enormous relevance is the fact that the Tijuca massif comprises the 39.5 square kilometers Tijuca National Park. Established in 1961, it is the most visited national park in Brazil. The strip of land that is the most densely populated portion of the buffer zone of the park is a perfect laboratory for watching the (geo)political instrumentalisation of the ecological discourse by agents directly or indirectly involved in the attempt to implement what could be termed a sort of non-murderous social cleansing.

A crusade has been carried out by the public prosecutor’s office (Ministério Público) for environmental and cultural heritage issues of the state of Rio de Janeiro. According to that office, the favelas located there are expanding rapidly and in aggregate form “a single spot comparable to Rocinha” (one of the largest favelas in Brazil and the largest one in Rio de Janeiro, whose population has been estimated at 200,000 inhabitants). Statements like this, as well as other comments made by public prosecutors, environmentalists, and others about the danger represented by the presence of informal settlements close to the park have been frequently published above all by Rio’s biggest newspaper, O Globo.

The corporate media has played a decisive role with regard to promoting an asymmetrical treatment of social classes by the state apparatus in Rio de Janeiro, and although the Ministério Público has been the main institutional agent of the current attempt to promote the total or partial removal of the favelas located in the Tijuca massif, it can be said that its role has not only been made public and highlighted but probably also stimulated by O Globo and other, mainstream media.

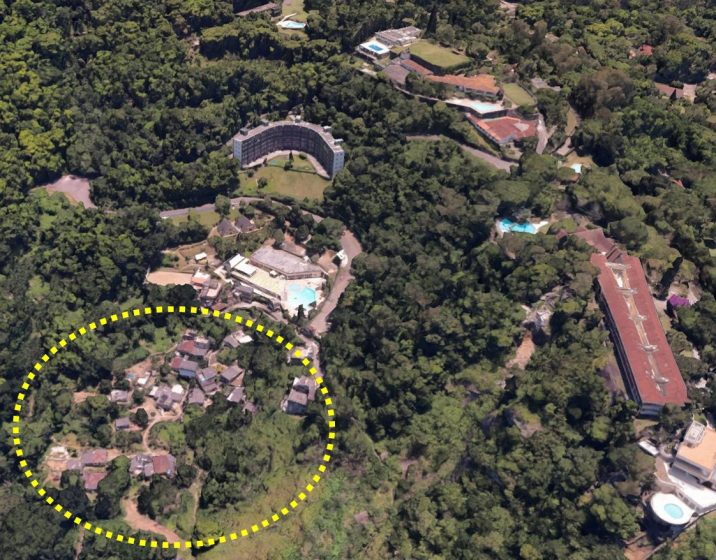

But the available data do not support the idea that the favelas of the Tijuca National Park’s buffer zone are expanding rapidly; according to reliable census data and even the municipal government’s own data, offered by the Pereira Passos Institute, this is far from being the case. Monitoring data based on satellite images from 1999-2013, carried out by Pereira Passos Institute, make clear that the spatial growth of favelas in the buffer zone ranged from nothing to very little (see Souza, 2016a, pp. 791-792). Ten years after it was proclaimed, in 2006, that the favelas around Tijuca were expanding rapidly, this statement can finally be declared false. Likewise, the contention that these mostly small favelas (see Figs. 1 and 2) are a threat to biodiversity can be declared contrary to fact. Moreover, while the Ministério Público and the corporate media continue their anti-favela crusade, residential encroachment of the buffer zone by the middle class is left undisturbed, even where it occurs close to a favela targeted for removal (see for instance Fig. 2). Clearly, the occupation of the same location by the middle class is not regarded by the state apparatus as an environmental threat. In fact, the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro has made it clear on more than one occasion how desirable would it be to increasingly attract financially well-endowed citizens to the area.

It must be explained that in Brazil, in contrast to mayors and governors, public prosecutors are not chosen through elections (as it is usually the case in the United States, for instance), but are instead civil servants who are chosen through a public tendering procedure. As a result, public prosecutors can be basically accountable only to their own conscience (although not few of them have also tried to attract media and public attention for several reasons), while a mayor or governor must take into account the feelings of potential voters directly and strongly. And favela dwellers are voters. Therefore, it is not difficult to see why in the Tijuca massif’s case the Ministério Público has recently been a more important actor than the City Hall itself as far as pressures on favelados are concerned. Curiously, the Ministério Público even pushed and prosecuted the former mayor Cesar Maia himself for (according to the prosecutor’s office) not doing enough to protect the environment from the threat represented by poor, informal settlements. Nonetheless, the fact is that the City Hall had tried to contain the expansion of favelas through highly controversial so-called “ecolimites” (fences or more usually walls surrounding the shanty-towns) since the beginning of the 2000s, allegedly for the purpose of protecting the remnants of the Atlantic Forest. The state government of Rio de Janeiro followed the same steps and its attempt to build a wall around Rocinha, Rio de Janeiro’s biggest favela, ended in what could be regarded as a media and public relations disaster for the then governor Sergio Cabral in 2009. Strong criticism came not only from Brazilian society but also from abroad, for instance the United Nations.

In a book chapter on New Delhi, Asher Ghertner used the expression “green evictions”—a happy choice of words to express a very unhappy situation. He points out the “metonymic association between slums and pollution”, what seems to justify for Indian courts “slum removal as a process of environmental improvement” (Ghertner, 2011:146, 147). If we expand the first remark a little bit—by means of including things such as environmental degradation and related ideas as part of the second term of that metonymic association—we can easily arrive at a description of Rio de Janeiro and many other, similar cases. In fact, “gentrifying conservationism” and “green evictions” (or “green displacement”, in more general terms) seem to be inextricably linked with each other, particularly (but by no means exclusively) in the Global South.

Factors such as the immediate cause or motivation, the role of specific organs of the state apparatus and of other agents (e.g. the corporate media and middle-class residents) and the way how affected poor people will react to threats of removal will obviously vary from case to case. However, one thing is certain: the spectre of “gentrifying conservationism” and “green evictions” will increasingly haunt segregated spaces and poor communities worldwide.

By way of conclusion I wish to raise a few questions, considering that ultimately the rulers (as well as their allies or funders: the media, business interests, and so on) usually try to convince us that there is a moral justification—namely to ensure the common good—for measures resulting in “gentrifying conservationism” and “green evictions”: Who defines, and on the basis of which parameters, in each particular circumstance, and in the context of specific power relations, what the “common good” is? How to justify morally the many situations in which asymmetries of treatment between rich and poor people can be observed? Where is the compelling evidence that there is a moral justification for sacrificing so often minorities in the name of the “common good”? In cases where, for reasons of safety of the affected persons themselves, a relocation of population is perhaps necessary or recommended, what has been done to adequately compensate for the material and even psychological sacrifices imposed on those who have to give up the places of residence to which they are accustomed? How can we assure that in such cases relocation takes place in a non-authoritarian way? Without persuasive answers to these questions, in the sense of consistency with strong social justice criteria, the “common good” type of explanation will be nothing but a poor excuse.

Marcelo Lopes de Souza

Rio de Janeiro

References

Ahlfeldt, G., et al. 2013. Game of Zones: The Economics of Conservation Areas. London: Spatial Economics Research Centres, London School of Economics/LSE (= SERC discussion paper 143).

Ghertner, D. A. 2011. “Green evictions: Environmental discourses of a slum-free Delhi” in Peet, R. et al. (eds.): Global Political Ecology. London and New York: Routledge.

Sandberg, L. A., et al. 2013. The Oak Ridges Moraine Battles: Development, Sprawl and Nature Conservation in the Toronto Region. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Souza, M. L. de 2016a. “Urban eco-geopolitics: Rio de Janeiro’s paradigmatic case and its global contexto”. City, 20(6), 765-785.

Souza, M. L. de 2016b. “Gentrification in Latin America: some notes on unity in diversity”. Urban Geography, 37(8), 1235-1244.

TNOC [The Nature of Cities]. 2014. Accessed November 9, 2015. https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2014/02/03/what-are-the-social-justice-implications-of-urban-ecology-and-how-can-we-make-sure-thatgreen-cities-are-not-synonymous-with-gentrified-orexclusive-cities/.

Leave a Reply