New modes of engaging with the urban landscape will not be based on superficial aesthetic concerns or sentimental rear-view thinking, but a celebration of the messy complexities and nuances of novel ecosystems, and the active role they will continue to play in the nature (and future) of our cities.

Volunteers. Exotics. Aliens. Weeds. Whatever happens to be your preferred nomenclature when describing the existence and behavior of spontaneous vegetation, it’s clear that many biases abound. We pluck, poison and mulch our landscapes to keep these decidedly untidy forces at bay. Yet have we also effectively mulched our mindsets? Have we blunted our ability to see these ubiquitous features of our everyday lives as anything other than botanical garbage? Might we benefit from taking a second, or a third glance at these novel ecosystems, perhaps even include them into our expanding definitions of “urban resilience”? A growing body of discourse and practice says yes.

First glances can be deceiving

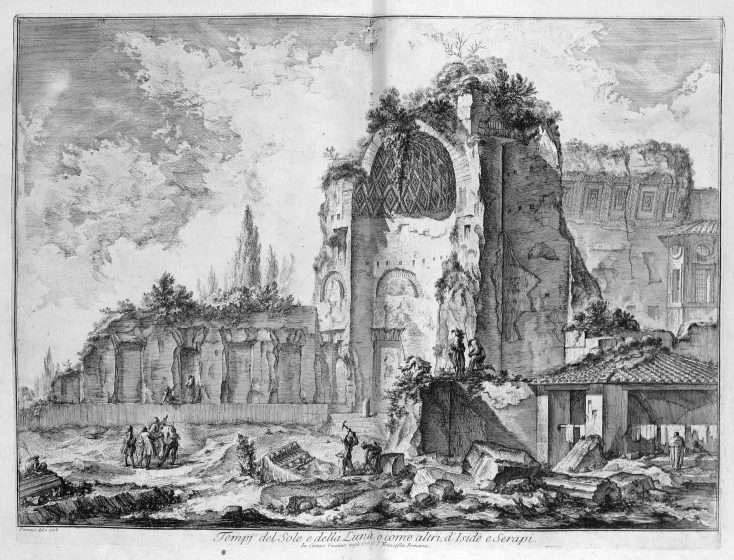

When famed Italian artist and cartographer Giovanni Battista Piranesi decided to depict the dereliction of 18th century Rome in his Vedute series, it was not by accident that he reserved amplified poetic license in expressing the ways weeds had taken over. Looking into the margins of these highly detailed etchings, one can’t help but ponder the role of common European weeds such as burdock (Arctium lappa) and common reed (Phragmites australis) emerging as central subjects, actively ravaging the skeleton of a once great city.

As they were in 18th century Rome, scenes like this have become commonplace at many scales within our human altered environments today, nibbling at the forgotten fringes of our yards and neighborhoods, teasing our ingrained notions of the natural. This is not Nature with a capital N, but rather “nature” in its more mischievous and subliminal form. The kind of nature that expresses itself in moments of self-willed ecological poetry: emerging from the shadows and cracks of the sidewalk, or in tangled masses along transportation corridors, or peeking defiantly through the tattered remains of post-industrial ruins.

It’s no wonder then that these messy “novel ecosystems” aren’t just seen as symptomatic of decline, but also symbolic of it, even contributive to it. But it’s precisely their special status as botanical boogie men that makes weeds so fascinating. At every turn, they seem to defy our instruments of control, and remind us of the chaos which lurks just beyond the veil of order.

Whether through the process of romantic imitation, clever marketing strategy, or scientific consensus, weeds have always signified the untamed, unwanted or feral aspects of our world—untidy nuisances to be disregarded, slowed, or even killed. One only needs to observe the campy television commercials for Roundup®, which typically feature an otherwise average domestic father figure temporarily transformed into a vigilante cowboy of the old west, battling a formidable band of vegetable outlaws. In place of a pistol is a spray wand containing Monsanto’s powerful glyphosate herbicide, armed and ready to chemically restore law and order to the untamed backyard frontier. Weeds in this context are often presented as anthropomorphized versions of themselves, an obvious attempt to exaggerate the pathology of their sinister intentions: thuggish thistles, dastardly dandelions and pick-pocket plantains.

But it’s not just suburban dads who vilify these common constituents of the urban ecosystem. Many professional ecologists and conservation biologists, with a longstanding disciplinary bias towards the study of native ecosystems and pristine wilderness conditions, have tended to study alien species exclusively through the lens of invasiveness. This lens has proven to be effective and arguably appropriate to understand the ways in which some botanical newcomers behave badly when introduced to a new territory—gobbling up resources, altering habitats, displacing native species, and generally wreaking havoc on the ecosystems they invade. The fact that the vast majority non-natives appear to integrate smoothly with their new neighbors is rarely emphasized.

In its third Global Biodiversity Outlook (CBO-3), the internationally funded Convention on Biological Diversity still lists the spread of exotic species as one of the biggest threats to planetary health and sustainability, citing a familiar shortlist of culprits which are laying waste to agriculture, spreading infectious disease, and so on (“Global Biodiversity Outlook 3” 2017). Emerging from this demoralizing narrative of loss and degradation is an elevated sense of threat with regard to all non-native species, and a range of land management practices that are based the continuing assumption that native is always good, and exotic is always bad.

This “green xenophobia” is powerful and pervasive, and impacts the ways we think and talk about urbanized landscapes too. Even the relatively nascent field of urban ecology to date has tended to direct much of it’s focus on more charismatic urban megaflora and “restorative” design solutions rather than fostering a deeper understanding of the feral and the funky. Driven by the desire to reconcile the (false) binary of “City” and “Nature”, these management and design strategies tend to disregard or supplant that which may already be thriving as an impediment to the establishment of “healthier” seeming ecosystems.

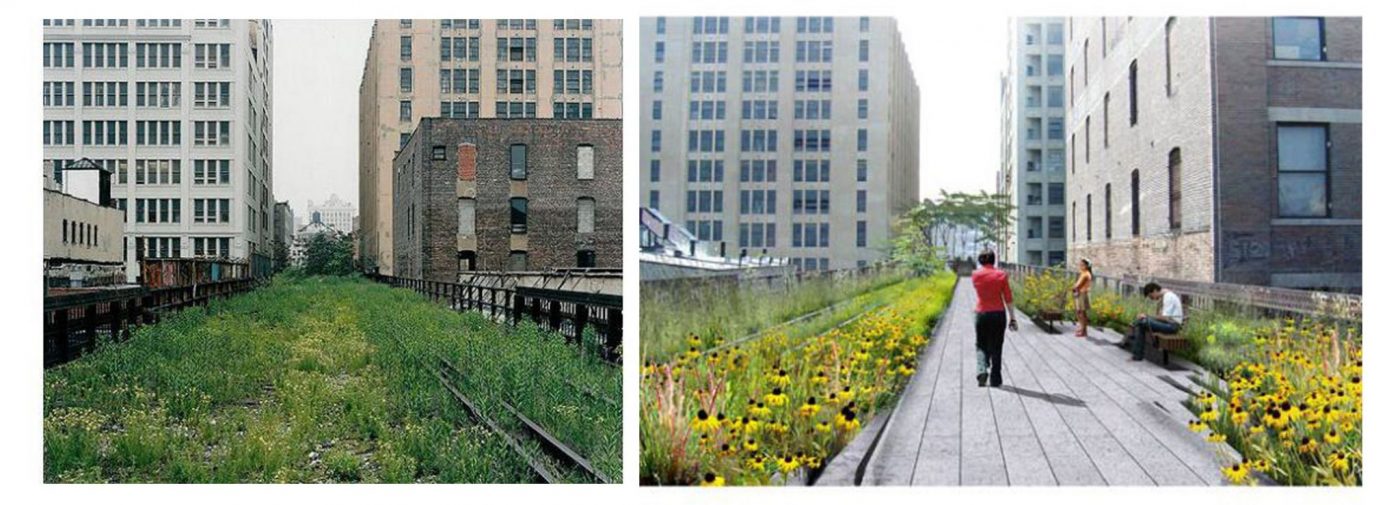

This phenomenon was recently reflected upon by Emma Marris in an apt critique she referred to as the “The Highline Problem”—in reference to New York City’s now iconic landscape darling designed by James Corner’s Field Operations. In its former condition as a spontaneous urban meadow on a defunct elevated railway in Chelsea, The Highline likely boasted a range of common weedy species such as tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima), fleabane (Erigeron canadensis), and mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris)—all of which are conspicuously absent from the plant palette in its formalized condition today. While noting the project as a gorgeous piece of green infrastructure, Marris questions the costs of this new arrangement in both biological and financial terms, noting the irony that a space which started as a self-willed cosmopolitan urban meadow with an effective operating cost of zero, now boasts the highest maintenance bill of any park in the city (“The Last Word On Nothing | Urban Wilderness and the ‘High Line Problem’ ” 2017).

Second glances as a call to arms

Because they’re less charming than their ornamental counterparts, and seemingly less trustworthy than their native counterparts, the odds are overwhelmingly stacked against the acceptance of weeds as a welcome expression of nature in our cities and in our everyday lives. Yet a growing body of contemporary creative practice and emerging research suggests that despite their unseemly appearance and dubious provenance, spontaneous urban vegetation may actually represent an unlikely expression of urban resilience, worthy of at least a second glance.

New nature writers such as the previously mentioned Emma Marris, Richard Mabey, and Fred Pierce, examine the deep and complex lives of these plants through lenses as far flung as history and folklore, to invasion biology and climate change (Pearce 2014; Marris 2010; Mabey 2010). In the space of academic ecology, researchers such as Peter Del Tredici, Ingo Kowarik, and Norbert Kuhn have dedicated their careers to understanding the dynamics of urban vegetation in all its forms. Del Tredici’s Wild Urban Plants of the Northeast: A Field Guide has been a staple reference for landscape and ecology students since it’s original publication in 2010.

A unifying theme in the work of these contemporary thinkers is the suspension of disbelief and judgment about non-native species to consider their potential merits as much as their potential risks. Their diverse modes of inquiry are not informed by typical knee-jerk presumptions of guilt, or mythologies of good vs. evil, but by observation and curiosity. Instead of judging species by their origins or aesthetics, they challenge us to consider their actual behavior and contextualize their role in the ecosystems they’ve become a part of.

Take, for example recent phytoremediation research suggesting that many ruderal species are highly effective “bioaccumulators”, capable of drawing up heavy metals like nickel and cadmium from post-industrial brownfield sites at prodigious rates (Kennen and Kirkwood, n.d.). Common plantains (Plantago major) seem particularly adept at plucking particulate pollution right from the air in the roadside environments they tend to inhabit (Weber, Kowarik, and Säumel 2014). Even dandelions (perhaps the most iconic among the uncharismatic urban microflora) have been studied as a vital early source of spring nectar to thirsty urban pollinators (“Urban Pollinators: Dandelion, Taraxacum officinale agg., 2017). In his groundbreaking book on the subject, Richard Mabey observes that weeds exhibit an uncanny ability to thrive in even the most disturbed, contaminated, and abused landscapes we create, noting that “What we ignore, more perilously, is the fact that many of them may be holding the bruised parts of the planet from falling apart” (Mabey 2010).

Many creative practitioners have also taken notice. Landscape architects such as Margie Ruddick, and David Seiter are among the forerunners of innovative new approaches to urban planting design and landscape management. Ruddick’s Wild By Design: Strategies for Creating Life-Enhancing Landscapes, and Seiter’s SUP (Spontaneous Urban Plants) have recently emerged as essential compendia for exploring the cosmopolitan wilderness conditions and potentials in cities like Philadelphia, and New York City. Itinerant Artist and writer Ellie Irons evokes weeds as both artistic muse as well as powerful political metaphor, and even paints with pigments derived from wild urban plants she’s collected. The so called No-Mow Movement in the United States and elsewhere has set its sights on understanding what happens when we intentionally forego the weed-whacker in certain areas of the city and rebrand these sites in a positive light. A growing contingent of amateur urban botanists have even emerged on Instagram (Plants of Babylon, The COMMONStudio, and LocalEcologist as just a few examples) all using 21st century tools to spot, identify and share their casual encounters with common urban weeds.

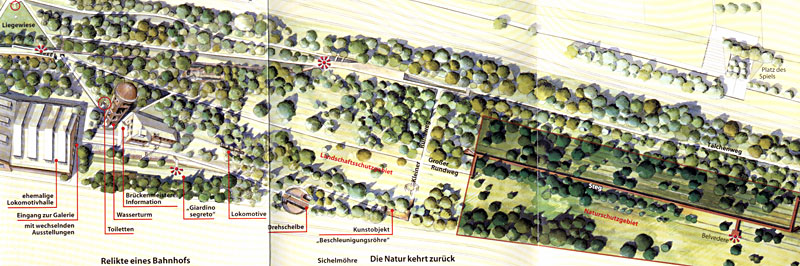

Perhaps one of the most exciting examples of formally “collaborating with chaos” can be found in Berlin’s Natur-Park Südgelände, a public park and urban nature reserve that is decades in the making. Originally used a freight rail yard, Südgelände was subsequently abandoned in 1952 and remained virtually untouched and forgotten for nearly four decades amid the economic, political and territorial disputes between East and West Berlin. When curious citizens and urban ecologists visited this territory just after the city’s re-unification in 1989, they were amazed to encounter the active processes of ecological succession playing out right under their noses in the heart of the city. In the spaces of unused railway tracks and open fields of sterile gravel, a novel and eclectic mode of nature had taken hold: Robinia trees, and extensive meadows containing ragtag mixtures of native and exotic wildflowers, dry grasslands, and shrubs (Kowarik and Langer, n.d.). Rather than erase the novel ecosystems that had emerged there, the design team conceived a plan that embraced them. Since it’s opening in 2000, this 18 hectare (44 acre) park has served as a thriving ecological sanctuary and community amenity, home to over 350 plant species, 47 fungi, 30 species of bird, 57 species of spider, as well as numerous wild bees and insects (“Natur-Park Suedgelaende, Berlin” 2017).

These second glances offer a way out of the limited conceptual traps of upholding “nativism at all costs”, and unlocks new narratives of vindication for plants and ecosystems that have been historically marginalized as “guilty by association.” In so doing, these important precedents are helping redefine what it means to live in a “post-wild” world, and challenging us to expand our outdated notions of what counts as nature—especially in our increasingly urbanized habitats.

Closer glances of the third kind

Novel urban ecosystems—and the exotic biota that inhabit them—are an unavoidable part of our ecological inheritance in the Anthropocene. Despite our best efforts to eradicate or control them, they are here to stay. And they will continue to move, colonize, spread and change. Alien species and “weeds” seem to occupy a distinct niche in our collective consciousness, marked by extreme prejudice, and narratives of loss. But might this be a by-product of our limited purview? Our first glances? A range of contemporary voices (writers, artists, scientists, and designers) are moving the needle on novel urban ecosystems, challenging us to give them at least a second glance. Yet there’s still a long road ahead to foster broader acceptance, and deeper understanding of how these messy systems work, and why they matter.

The cases and thinkers cited here should surely stand as a compelling challenge to designers, ecologists, and policy-makers to follow suit. Third glances, then, are those that are still yet to come. Imagine the stories that are yet to be told, the scientific insights yet to be made, the landscape conditions and experiences that have yet to be nurtured. Is it possible that there are latent virtues in these messy ecosystems that are still awaiting discovery? How might we better incorporate the feral aspects of urban nature into our worldview, our research, our creative practice? How might we continue to work toward better understanding, measuring and incorporating the benefits of novel ecosystems, while minimizing the risks?

It’s time to allow these seeds of possibility into our collective discourse about urban resilience, and give them time and space to grow, un-mulched. What’s at stake in these new mindsets is not just the fate and perception of “weeds” in our world, but the emergence of new modes of urban environmentalism. These new modes of engaging with the urban landscape will not be based on superficial aesthetic concerns or sentimental rear-view thinking, but a celebration of the messy complexities and nuances of these systems, and the active role they will continue to play in the nature (and future) of our cities.

Daniel Phillips

Bangalore

References

“Global Biodiversity Outlook 3.” 2017. September 3. https://www.cbd.int/gbo3/?pub=6667§ion=6700.

Kennen, K., and N. Kirkwood. n.d. “Phyto: Principles and Resources for Site Remediation and Landscape Design.” https://www.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=0b_lCAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Phyto+kirkwood&ots=rZzkKQtkPy&sig=u4ZYErg_QmbDistsWjr8P5AxqvM.

Kowarik, I., and A. Langer. n.d. “Natur-Park Südgelände: Linking Conservation and Recreation in an Abandoned Railyard in Berlin.” http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/3-540-26859-6_18.pdf.

Mabey, Richard. 2010. “Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants.” https://scholar.google.hu/scholar.ris?q=info:Zdqe_Hi2tuMJ:scholar.google.com&output=cite&scirp=0&hl=en.

Marris, E. 2010. Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World. https://www.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=NXF4AAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA173&dq=rambunctious+garden&ots=SabNFPBg7U&sig=gh0nsHkvNNv910FJyUYS5zOPON0.

“Natur-Park Suedgelaende, Berlin.” 2017. September 3. https://www.gardenvisit.com/gardens/sudgelande_nature_park.

Pearce, Fred. 2014. The New Wild: Why Invasive Species Will Be Nature’s Salvation. https://scholar.google.hu/scholar.ris?q=info:dg0ljllhCV8J:scholar.google.com&output=cite&scirp=0&hl=en.

“The Last Word On Nothing | Urban Wilderness and the ‘High Line Problem.’” 2017. September 3. http://www.lastwordonnothing.com/2017/05/01/urban-wilderness-and-the-high-line-problem/.

“Urban Pollinators: Dandelion (Taraxacum Agg.) – a Valuable Food Source Not Only for Pollinators.” 2017. September 3. http://urbanpollinators.blogspot.com/2013/12/dandelion-taraxacum-agg-valuable-food.html.

Weber, Frauke, Ingo Kowarik, and Ina Säumel. 2014. “Herbaceous Plants as Filters: Immobilization of Particulates along Urban Street Corridors.” Environmental Pollution 186 (March): 234–40. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749113006441.

Leave a Reply