What is striking in Méréville is the conjunction between the cultural creation of a “natural” landscape and the way in which this landscape has evolved. Nature has, little by little, regained its rights, thanks to the gradual abandonment of the estate in the course of its history. To an undiscerning eye, the garden now appears as a natural valley in which the meanderings of the river, the groves, rocks, caves, and other waterfalls seem to have existed from time immemorial. This soothing landscape, pleasant for walking and meditation, seems just out of a painting by Hubert Robert! http://www.essonne.fr/no-cache/diaporama/diapo/domaine-de-mereville/

Over several years of research and work on protected natural areas, especially in urban areas, I have observed how humans manage this “nature”, which is considered as wilderness. In the gardens of Méréville, I found myself faced with the same type of paradox created by human intervention on natural environments: Can a landscape that has undergone human intervention still be considered “natural”? If the resulting “cultural nature” is not less rich in native biodiversity, why would its conservation value be lessened as compared with other areas considered “wilderness”?

In the case of Méréville, man created an irregular garden in which he sought to reproduce the idea of nature, as conceived in the 18th century. This was a romantic nature, idealized and punctuated by the follies that make it so picturesque, while recalling the links of man with the natural world. Time has made the imagined landscape truer than nature itself.

Hiking in the historical garden is a bit like exploring a natural protected area. Its panoramic structure seeks to reach the great wild landscapes and create the effect of surprise and admiration on the visitor, as an explorer discovering “wild” nature. Here is a meander of river, an island, a lake; there are rocks and caves; and for the adventourous who dare advance to the bottom of the park, there is a great waterfall with rustling waters.

In the case of urban protected areas, and protected areas in general, men intervene to protect, manage and preserve a space considered as natural, in a way that recalls the gardener caring for his garden. The very fact that there is human intervention, to manage and protect biodiversity, guides the evolution of the protected area and transforms it de facto from a natural place into a cultural place, or even an artefact, into the etymological meaning of the term, “made by the hand of man”. Nature thus meets culture, which does not prevent it from enriching itself by this “fertilization”.

The conservationists will forgive me my audacity, but can we speak of a “natural area” in the case of a “domestic nature”, even in a national park with big cats? The evolution of the nature and the culture concepts opens our mind to that of “cultural nature”. It has been demonstrated in the Amazon Rainforest, which is a “garden” cultivated by the Amerindians for their needs for the centuries (Hladik, 1996); in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Mumbai, where tribals cultivate and find medical and food plants among the highest density of leopards in the world; or in the Tijuca National Park in Rio, a “cultural” forest replanted by men. The recognition of the “cultural nature” value could contribute to integration of traditional knowledge into the management actions of protected areas. The survival of the Nairobi National Park, Kenya, depends to a large extent on the traditional Maasai knowledge to maintain the seasonal wildlife migratory corridor, linking the south of the park with the Athi Kapiti Plains, the “Maasai Garden”.

The hand of the man who protects and manages a so-called “natural” area in order to conserve it does not, in any way, diminish the importance of conservation actions or the value of the landscapes and the biodiversity conserved. Rather, the growing awareness of the need for human intervention and the beneficial transformation that it can bring about should lead to fundamentally different conservation practices. For it means to recognize man as part of nature and his responsibility, both in its transformation and preservation.

In Méréville, human intervention is the basis of the landscape built. There, conservation issues of the natural and cultural heritages intertwine. Most of the large trees planted in the 18th century were replaced or simply cut out by former landowners, in particular a forestry tradesman. But in this place preserved from visitors for several years, the herbs have pushed everywhere, good and bad. The river, whose bed has been moved and traced to draw curls, to throw itself into large and small waterfalls and to cross lakes, has gradually faded and flows slowly, as if for it time had stopped. The rocks and caves, covered with vegetation and blackened by the centuries, have such a “natural” character that they would deceive the most knowledgeable climbers. Many follies of the 18th century garden were sold and exiled to Jeurre Estate, 20 km further north. The remaining follies, including the castle almost in ruins and the “Swiss farm”, accentuate the natural character of the landscape, now housing a fauna and flora so important that it is classified a “Natural Area of Ecological, Floristic and Faunistic Interest” (ZNIEFF: Zone naturelle d’intérêt écologique, floristique et faunistique; https://inpn.mnhn.fr/zone/znieff/110001587). The protection of this area was motivated by the presence of wetland habitats of patrimonial interest (wood of alders, willows and sweetgale).

The parallelism between a natural area and a cultural site is not obvious, but it allows us an interesting reflection on the different levels of intervention and the power games played in the protected sites whether natural, such as a national park, or cultural, as a heritage site. The UNPEC research program (Urban National Parks in Emerging Countries & Cities, 2012-2016) analyzed the linkages and the relationships between the multiple stakeholders interacting with this type of protected area, managed at the national level, in a local (city) and regional (state, county, region) context and whose status, particularly symbolic, is strongly influenced by the international bodies.

In 2016, the Department of Essonne, owner of the Méréville Estate, decided to reopen the gardens to the public. The project involves a slew of stakeholders from many institutions. They come from the level of the French National State (Heritage Site, Archaeological Service, Environmental Department, etc.); the Ile-de-France Region, where it is located, the Department of Essonne itself and the Méréville Municipality, but also the Agglomeration of which it is a part. In 2017, the Department of Essonne has created the “Essonne Mécénat” Foundation, to look for financial support for the conservation, restoration and improvement of the Department’s natural and cultural heritage, including the Méréville Estate (http://www.essonne.fr/le-mecenat-au-service-de-lattractivite-de-lessonne/). This new public-private partnership initiative is still quite innovative in France. As part of this logic, a call for projects was launched with the aim of establishing a public-private partnership for the restoration of the castle, the main folly of the garden, which is now almost in ruins (https://fr.calameo.com/read/003221600d33fca1193d8).

The restoration of the garden and its hydro-ecological system reveals some contradictions of environmental and heritage law. From the environmental point of view, the ecological integrity of the river must be restored and the obstacles created by man destroyed. It means destroying the waterfalls and lakes created in the 18th century. A hypothesis unimaginable from the cultural heritage point of view. The rehabilitation project of the historic paths calls for the expertise of archaeological excavations (National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research). For every path traced, every grove site, every meander of the river, every rock, was thought to build this surprising landscape. Therefore, to meet the requirements of one law, technical choices require compromises with the other.

Chris Sandbrook speaks of plural conservation in the 21st century, and proposes a fairly wide definition which encompasses the diversity of conceptions of what nature conservation can be today: “actions that are intended to establish, improve or maintain good relations with nature” (Sandbrook, 2015, p.565). This plurality could also be applied to the conservation of cultural heritage.

While conservation is now composed of multiple means and various actions for natural and cultural sites, each one, in its cultural, socioeconomic and political context must find where to position the cursor between a traditional form of conservation, and opening up to the territory as well as its actors and inhabitants.

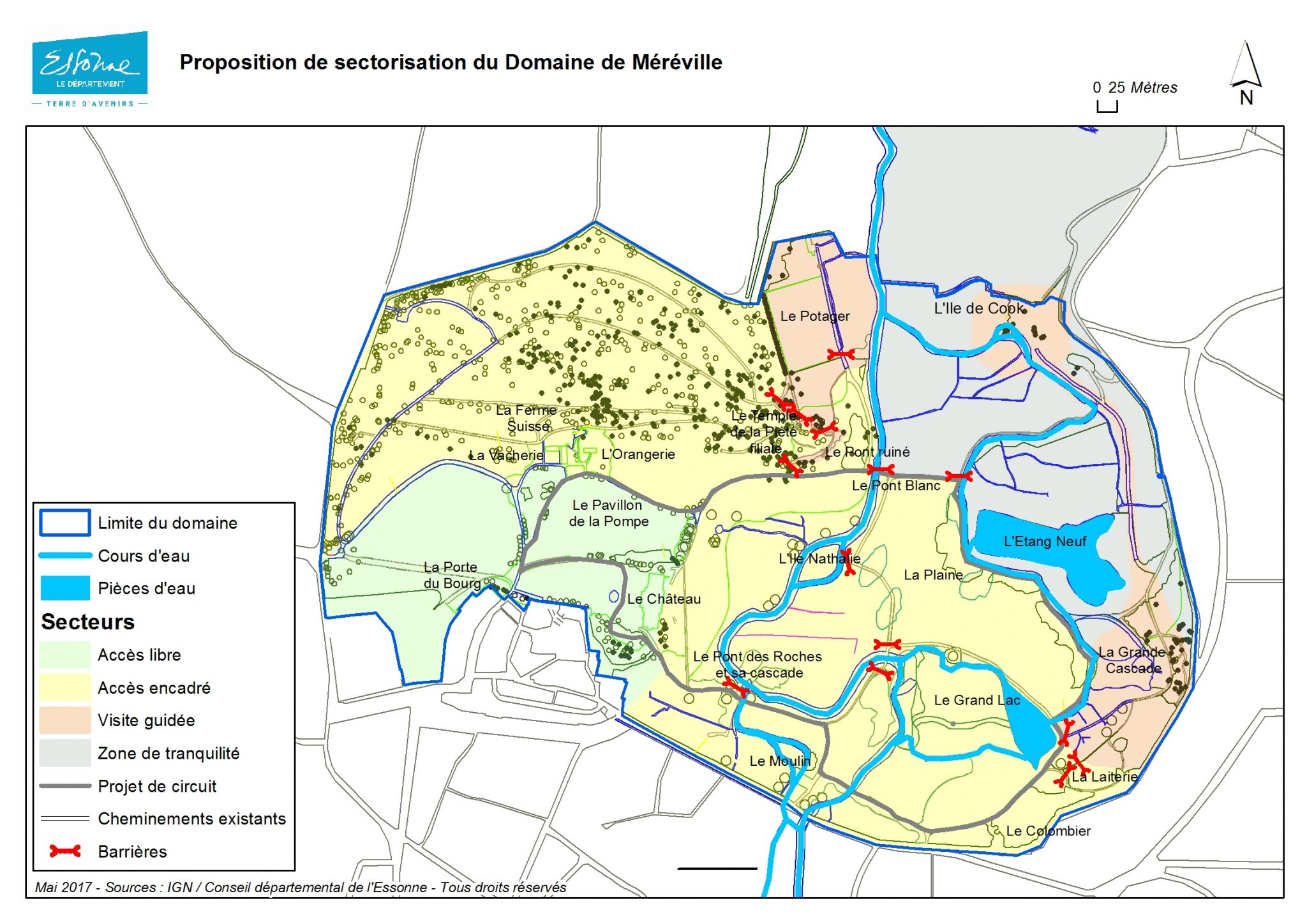

The new pond, created in Méréville in the early 20th century, is hidden discreetly in the meadow. It has become a refuge for wildlife, especially for birds such as the grey heron, looking for a secure breeding site on their migratory route. This element in particular has inspired a proposal for sectorisation of how the Méréville Estate, itself inspired by the sectors of national parks such as Table Mountain, Cape Town, and Tijuca, Rio. This system makes it possible both to regulate and secure visitation, and to protect the biodiversity of the site, including preserving certain areas from anthropogenic disturbance. The internal rules complete the protection of the natural and cultural elements of the site and the visitors.

But the park today (58 ha) is only a fragment of the 18th century property (400 ha). Beyond the walls, urbanization has come to nibble fields and forests but left in the valley floor marshes, now classified as Sensitive Natural Areas (ENS: espace naturel sensible) property of the Department of Essonne.

These natural areas follow the river for more than 2 km until the small village of Boigny. There are the stone quarries named “Carrières des Cailles”. It is one of the thirteen protected sites of the Essonne Natural Geological Reserves (http://www.reserves-naturelles.org/sites-geologiques-de-l-essonne), which are the witnesses of the last marine transgression at the Paris basin (-33.7 and – 28 million years).

This could lead to changes in the management of heritage areas, both natural and cultural, particularly in urban and peri-urban areas, and to definitively integrate the value of human intervention into a proactive conservation.

Louise-Lézy Bruno

Paris

[1] The Stampien is both an age of the geological timescale and a stage in the stratigraphic column. LOZOUET P., 2012

References

M., HLADIK A., PAGEZY H., LINARES O., KOPPERT G. et FROMENT A. dir., 1996, L’alimentation en forêt tropicale : Interactions et perspectives de développement. Paris, UNESCO, vol. I, 639 p. http://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/divers09-03/010009721.pdf

BARIDON M., 1998, Les Jardins, Paysagistes, jardiniers, poètes, Coll. Bouquins, Robert Lafon, Paris, 1260 p. http://www.bouquins.tm.fr/site/les_jardins_paysagistes_jardiniers_poetes_&100&9782221067079.html

SANDBROOK C. “What is conservation?”, Oryx, 2015, 49(4), 565-566© 2015 Fauna & Flora International. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/oryx/article/what-is-conservation/01CD7B55A1D009475B9A83ED15C78468

LOZOUET P., 2012, Stratotype Stampien, Editions Biotope, 460 p. https://www.abebooks.fr/Stratotype-Stampien-Lozouet-P/11487880954/bd

About the Writer:

Louise Lezy-Bruno

Louise is Deputy Director of the Environment in the Paris Region. An Architect-Urban Planner with a PhD in Geography, she works on the cities-nature relationship. She is a member of the IUCN-WCPA.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation