Most of the narratives on the crises of development are woven around rapid population growth in developing countries. Yes. The number of world citizens is over seven billion. The challenges that this number raises far exceeds national and intergovernmental agencies’ abilities to address them. Rapid urbanization is but one of the key challenges in the developing countries.

Many scholars and researchers grasp some understanding of the extent of the speed of urbanization in developing countries through spatially explicit or discreet models that point out some significant changes. For instance, the disappearance of open and green spaces, encroachment of buildings on watershed areas increases social and biophysical vulnerability of urban areas. Such issues and challenges are often repeated discussions between policymakers, environmentalists, planners and other stakeholders. In most cities, people look up to governments for solutions to crises and vulnerabilities. Is the public sector—through the policymakers and decision makers—always the springboard of urban resilience? Considering the multiple dimensions of urban sustainability challenges in Africa, the answer is certainly no.

Since the 1970s and 1980s the phrase “future generations” is clichéd in many environment and sustainable development circles. The unborn generations of the late 20th century were born into the world that is so much urbanized and replete with vulnerabilities, uncertainties, complexities and ambiguities that were well understood during the late 1970s through the dawn of the new millennium. This young generation of the new urban age are called millennials. There is an urbanized planet where resilience of its biophysical and cultural components is the only guarantee of its survival.

Many urban centers of African countries experience youth bulge and unprecedented youth unemployment. In many African countries the youth are marginalized and excluded from political and economic architectures in spite of their dominance in population pyramids of African countries. Indeed, a resilient city is one that promises the future of the young generation. While growing up, the young generation enrich their life-long experiences through their landscape experiences. Green areas and open spaces in many African cities provide the children with avenues for peer play and pastimes. Children gather fruits from trees, play with butterflies and insects and make some reptiles their pets. This is the ecological school that forms the life of the young generations.

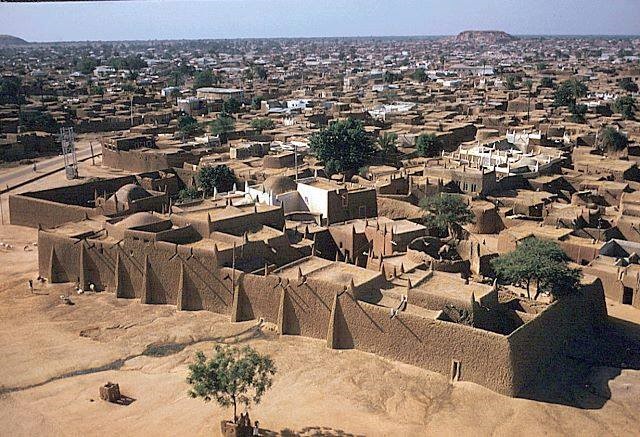

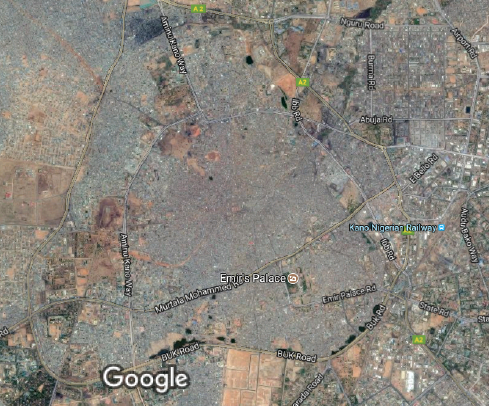

Unfortunately, rapid urbanization and poor planning institutions in many urban areas in Africa has undermined the priceless ecosystem services that urban areas offer to the young generation. The young generation are not the only losers but they could be the most severely hit by several consequences of urbanization which may be exacerbated by climate change and poverty. Kano City in Northern Nigeria is one of the ancient pre-colonial African cities whose history dates back to the 10th century. According to some historical accounts, around the 16th century Kano was the third largest city in Africa after Cairo in Egypt and Fez in Morocco (Barau et al, 2015). The city is located in the West African drylands. It is prone to droughts and famine and yet it counts as one of the most resilient cities in Africa. Land management—through agroforestry—raising of trees in farm lands and institutional management of urban open and green spaces strengthened the attributes of the city’s resilience which has only waned and collapsed towards the last quarter of the last millennium.

Prior to the two, back-to-back major international conferences, ISCC and Resilience 2017 held in Stockholm, Sweden, there was an effort to showcase innovative ideas that can support implementation of sustainable development goals (SDGs). The SDG Labs emanate from joint works of the Future Earth, Stockholm Resilience Centre and University of Tokyo.

Prior to the two, back-to-back major international conferences, ISCC and Resilience 2017 held in Stockholm, Sweden, there was an effort to showcase innovative ideas that can support implementation of sustainable development goals (SDGs). The SDG Labs emanate from joint works of the Future Earth, Stockholm Resilience Centre and University of Tokyo.

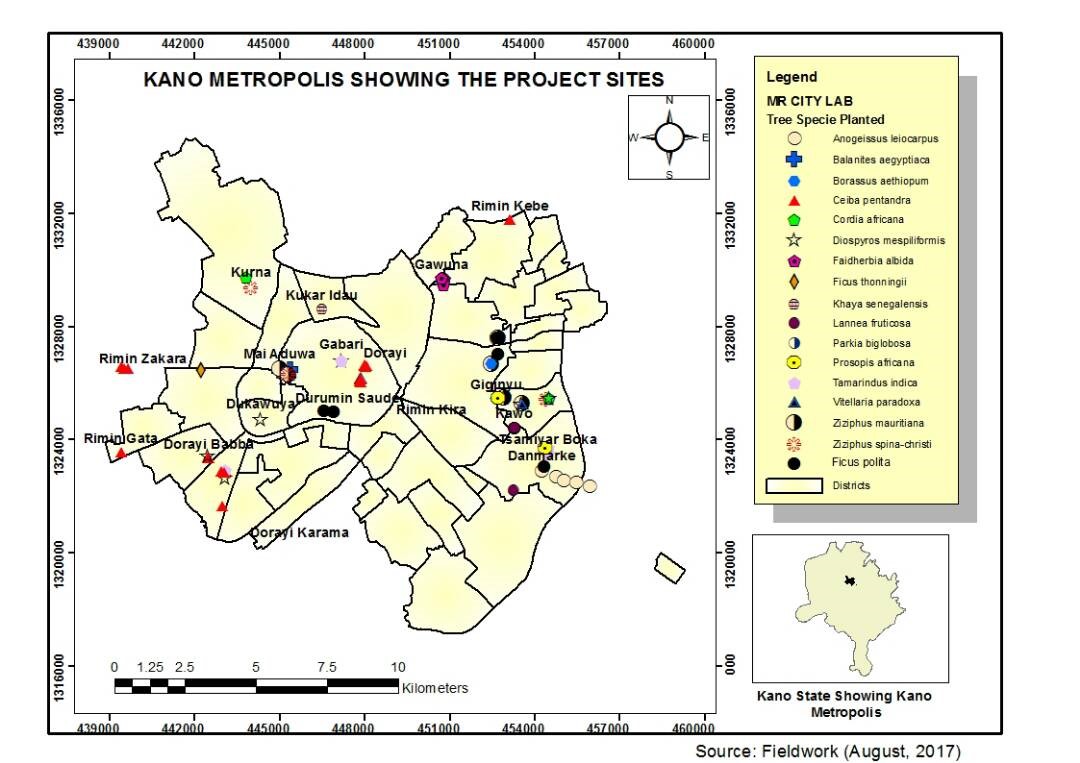

Because urban Kano is at the centre of the storm of collapsing city resilience an idea of restoring local tree species through the efforts of millennials was proposed by the city’s Bayero University Kano. The proposal is tagged as MR CITY Lab an acronym for Millennials and Resilience: Cities, Innovation, and Transformation of Youths Laboratory.

MR CITY Lab, just like other SDG Labs, was selected based on its innovative attributes, primarily its focus on the younger generations as the driving force of restoring urban resilience through restoring the local tree species of the savanna. The friendliness and affinity between people and trees in urban Kano is unique and fascinating one. Many neighborhoods in Kano are named after different indigenous tree species (see Table). Linguists called the art and practice of naming places after some phenomenon as toponym. The neighborhoods that bear tree toponyms are centuries old. Unfortunately, in most of these neighborhoods one can hardly see any of these namesake local tree species. Even worse, young urbanites would tell you that they do not know and cannot even recognize such plants.

At MR CITY Lab, we believe that trees are important in helping cities and communities to realise SDG 11–Sustainable Cities and Communities and SDG 13—Climate Action and many targets under these the two goals. Our approach is practical. We used university student millennials to make contact with communities and subsequently introduce the tree species into the neighborhoods with tree toponyms.

| S/N | Places | Tree species name | Longitude | Latitude |

| 1 | Rimi Market | Ceiba pentadra | 8.51573 | 12.0004 |

| 2 | Rimin Kebe | Ceiba pentadra | 8.55131 | 12.0456 |

| 3 | Rimin Gata | Ceiba pentadra | 8.44102 | 11.9715 |

| 4 | Durimin Iya | Ficus polita | 8.52602 | 11.9909 |

| 5 | Dorayi Babba | Parkia clapatoniana | 8.47656 | 11.9569 |

| 6 | Dorayi Karama | Parkia clapatoniana | 8.4534 | 11.9643 |

| 7 | Dorawar Yankifi | Parkia clapatoniana | 8.45558 | 11.9782 |

| 8 | Chedi | Ficus spp | 8.51911 | 12.0018 |

| 9 | Chediyar Yangurasa | Ficus spp | 8.51007 | 12.003 |

| 10 | Kukar Bulukiya | Adansonia digitate | 8.50594 | 12.0113 |

| 11 | Gawuna | Faidherbia albida | 8.55874 | 12.0328 |

| 11 | Dan Marke | Anogeissus schimperii | 8.56879 | 11.9832 |

| 13 | Mangwarori | Mangifera indica | 8.50271 | 11.9924 |

| 14 | Gabari | Acacia nilotica | 8.512625 | 12.00223 |

| 15 | Kurnar Asabe | Ziziphus spina-christi | 8.483041 | 12.05291 |

| 16 | Giginyu | Borassus aethopium | 8.577825 | 11.99117 |

| 17 | Tsamiyar Boka | Tamarindis indica | 8.568871 | 11.97791 |

| 18 | Wali Mai Aduwa | Cajanus cajan | 8.484699 | 11.98801 |

| 19 | Durumin Saude | Ficus polita | 8.514247 | 11.98523 |

| 20 | Dorayi | Parkia clapatoniana | 8.522907 | 12.00171 |

| 21 | Madatai | Khaya senegalensis | 8.514038 | 11.99687 |

Most of the trees that were restored are of immense economic importance and industrial utility. For instance, the fruits of Acacia nilotica tree are used in tanning hides and skin—one of the traditional industries in Kano. The city used to export tanned leather to Morocco and parts of Europe in the pre-colonial periods. The residue of the fruits from the tanning pits are used for fattening animals. On the other hand, the modern tanneries are powered by fossil fuels and depend on heavy toxic chemicals that pollute rivers and waterways both within and outside the city. Most of the trees that MR CITY is reintroducing to the city are beneficial to human health because their fruits, leaves and roots provide local foods, drinks and medicines.

The experiences of MR CITY attest to the power of youth in rebooting elements of urban resilience in Africa. The millennials have the capacity and energy to engage their peers, younger children and also the older generations who look up to their innovative energies, aspirations and commitment to rebooting environmental wellbeing and welfare. Thus, it is crucial for municipalities in African countries and beyond to tap into the hidden talents of millennials to achieve the SDGs.

Aliyu Barau

Kano

References

Barau, A.S. (2016) The Royal Bats of Kano City. https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2016/03/20/the-royal-bats-of-kano-city/

Barau, A. S., Maconachie, R., Ludin, A., & Abdulhamid, A. (2015). Urban morphology dynamics and environmental change in Kano, Nigeria. Land Use Policy, 42, 307-317.

Strain, D. (2017) Spotlight on SDG Labs: Trees grow in Kano. http://www.futureearth.org/blog/2017-aug-23/spotlight-sdg-labs-trees-grow-kano

Add a Comment

Join our conversation