Gaining local commitment and support was crucial to success, and remains so today.

Looking back over 50 years working as an ecologist some things stand out as real success stories. Camley Street Natural Park in London is one of these. On the day that I started work as Senior Ecologist at the Greater London Council (GLC) in 1982 I learnt that the Council had decided to convert a derelict coal yard at the back of King’s Cross railway station into an ecology park. It was in one of the most deprived areas of inner London, surrounded by post-industrial dereliction. It was up to me to make it happen, along with many other innovative projects that formed the GLC’s dynamic new programme for ecology in London during the 1980s.

The coal yard had been acquired in 1981 by the GLC to provide a parking lot for long distance coaches. But things had changed in the meantime. The Council was now a Labour administration led by Ken Livingstone who was known to have strong environmental concerns. Added to that a forceful new Controller of Development, Audrey Lees, brought a wealth of experience in ecological planning. There was also a new pressure group, the London Wildlife Trust, formed to protect areas of value for wildlife. It was a group of local residents affiliated with this new body who had successfully lobbied the GLC to turn the coal yard into an ecological park.

I quickly found that life as an urban ecologist was remarkably varied; dealing with everything from overall strategic plans of bodies like the Corporation of the City of London to detailed consideration of individual sites with local community groups, often in some of the most deprived parts of the capital. So it was in the case of Camley Street Park, when I found myself going straight from a formal session in the Guildhall to a meeting with residents of Somers Town, at that time a district of rather ill-repute. My job was to explain how the Greater London Council intended to convert the derelict coal yard into an ecology park. But I was well aware that in this neighbourhood the whole idea could be easily ridiculed. People were far more likely to be concerned about homes and jobs. I arrived feeling out of place in a city suit and quickly removed my jacket and tie, walking into the community centre with shirt-sleeves rolled up.

I wanted to show images of the kind of place that might be created. There were very few examples to draw on but I had some shots of the William Curtis Ecology Park at Tower Bridge with children pond-dipping. A wetland theme seemed appropriate as the coal-yard lay beside the Regents Canal, so I really needed some good photos of wetlands. I ended up using photos of National Nature Reserves that I was familiar with. They were a far cry from central London, but I had to risk it. When the lights came on there was a long silence and my heart sank. Then there came a deep chuckle from the depths of an armchair and a lady said “Do you know, this is the first beautiful thing that has happened to us here”.

I knew from that moment we had local residents on our side. The next step was to ensure that some of them were on the management committee. They were delighted to be asked and some were intimately involved for many years. I soon realised that they were crucial to success of the whole venture. Within the GLC it was called community liaison, but that doesn’t do it justice. Engagement might have been a better word but it went much further than that. We recognised the need not just to engage with the local community but to have local residents involved in every aspect of the project. When we excavated to make the ponds we found a Victorian rubbish dump full of bottles and broken pottery. People fell upon them with glee and nearby houses are still full of these artefacts. Children from local schools made a mural from the fragments. As each stage in creating the park was completed we celebrated with a barbecue or other festivity. Jacqui Stearn, the first full-time project officer worked with local people whilst the park was being created. Her role was crucial to our success. She was one of the locals who lobbied to get the place protected as an ecology park. Later she brought national attention to the project when she won the annual Kenneth Allsop Literary Prize with an essay about Camley Street published in the Sunday Times in 1984.

At that time the concept of an ecology park was still very new. People had very different views on what might be achieved. Some of those who had lobbied for retention of the overgrown coal yard wanted to keep it as it was, as an example of natural colonisation. I took a different view, arguing that the park would have much greater potential for environmental education if it was designed with that in mind. I could also see great advantages in developing a wetland theme. During 1982 GLC landscape designers and ecologists worked together to draw up plans for the park, in consultation with the local wildlife group. Fergus Carnegie was assigned to the job of landscape designer, but he freely admitted that he knew very little about ecology. My knowledge of landscape design was equally lacking. But between us we came up with a workable plan. Indeed the result was a great credit to Fergus who managed to create a remarkably intimate and natural feel within the confines of a very small site. The fact that it is still there today is largely due to the effectiveness of the original design and the considerable care that went into its construction. The GLC was used to doing much bigger construction projects. A capital budget of over £300,000 allowed this high profile venture to be done well.

Ensuring that we got the ecology right was another matter. It was my job to select suitable plants. That’s easy in theory but we soon ran up against problems of obtaining native species from horticultural suppliers. Deliveries of even the commonest wetland species such as purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), ragged robin (Lychnis flos-cuculi) and marsh marigold (Caltha palustris) all turned out to be cultivars. At that time there seemed to be no way of obtaining commercial supplies of common reed (Phragmites australis) or bulrush (Typha latifolia). That was early 1984. Thirty years later the situation is totally different with many suppliers providing native stock for a wide variety of habitats. With these early frustrations overcome the landscaping was completed very quickly and like many other newly created wetland habitats the whole place had a remarkably natural feel within only eighteen months. I remember an excited phone call from the resident teacher telling me that a heron had arrived. It was standing precisely as portrayed by the artist in our publicity brochure. It seemed we had its stamp of approval.

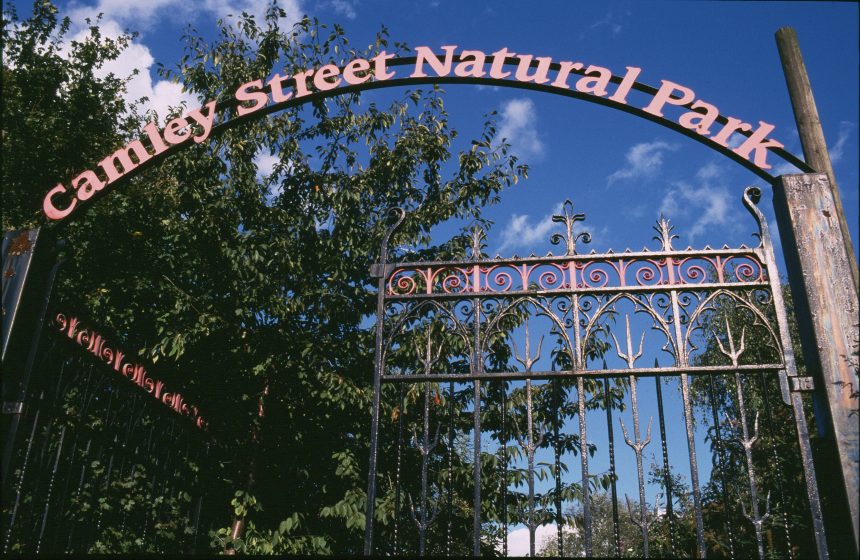

The park was opened by Ken Livingstone, with great celebration by the local community, in May 1985 and it became an immediate success. With abolition of the GLC in 1986 it was leased to the London Wildlife Trust and quickly became one of their flagship nature centres. The main purpose of the park was to provide an opportunity for children in central London to have direct contact with nature. It was soon booked solid by local schools, attracting 10,000 schoolchildren every year by 1990. The park also attracted visitors from far and wide as a demonstration project. As interest in urban nature grew worldwide Camley Street achieved a certain fame among practitioners and brought an endless stream of visitors from Europe, Japan, South Africa, North America and more recently from China. But it was also popular with local people of Camden and Islington as a place of peace and quiet at weekends. The local community has continued to be closely involved. Volunteers have ensured that the park is kept open on weekends and there has been a succession of environmental festivals and other events for local people. Some of the young children who were involved at the beginning continued to take an interest as teenagers, and I remember one incident where a youngster confronted others saying, “Don’t you touch those trees. I planted those!”

Camley Street Natural Park is still there today despite a succession of planning proposals threatening its existence, including the extension of St. Pancras Station for the Channel Tunnel rail link. Local people who recognise that they have something very special have fought them all off. So what was it that made it so special? In essence it was having nature on the doorstep. For people living in one of the most deprived neighbourhoods of inner London it provided a remarkable link with the natural world. In the early days I met a family there one Sunday evening. They were totally engrossed in pond dipping. The children, who had already visited the park with their school, had taken their parents and grandparents to share the experience. By the end of the evening their grandfather was extremely proud to tell me that he had identified four species of dragonfly and he had never set eyes on one before. He was entering a new world.

Creating Camley Street Natural Park taught me many things. Gaining commitment and support from local people was crucial to its success and remains so today. That depended on a vision that local residents could embrace—“The first beautiful thing that has happened to us here”. But it also needed a sound philosophy that would work, crossing boundaries between ecology, nature, poetry and art that together provide a very special experience. It made me realise that much can be achieved through cooperation between ecologists and landscape designers, who are so often working poles apart. As in any major undertaking finance was crucial to success. Camley Street Natural Park was not constructed on a shoestring budget. The GLC ensured that the landscaping was built to last, and so it has. Then there was the politics. Having strong political backing was perhaps the most critical factor. It gave the whole project kudos way beyond its scale. This tiny park is acknowledged for its success all around the world. I am proud to have played a part in the story.

David Goode

Bath

A shorter and less detailed version of this story was contained in Nature in Towns and Cities David Goode 2014 published by Harper Collins.

Leave a Reply