A review of The Lost Rivers of London, by Nicholas Barton and Stephen Myers, 2016. ISBN:1905286511. Historical Publications Ltd . 224 pages. Buy The Lost Rivers of London.

…and London’s Lost Rivers, by Paul Talling. ISBN: 184794597X. Random House UK. 192 pages. Buy London’s Lost Rivers.

Beautifully written with a wealth of detail, The Lost Rivers of London, by Barton and Myers, provides an invaluable historical perspective on the fate of many small rivers that still flow beneath the streets of London. The course of each river has been identified from historical records, paintings, photographs and maps, including one of the earliest maps of London dated 1559.

Beautifully written with a wealth of detail, The Lost Rivers of London, by Barton and Myers, provides an invaluable historical perspective on the fate of many small rivers that still flow beneath the streets of London. The course of each river has been identified from historical records, paintings, photographs and maps, including one of the earliest maps of London dated 1559.

But the book is far more than a history of the rivers. It tells the story of London through the treatment of its rivers; how development and expansion of the city depended on availability of fresh water; how the rivers were modified and canalised to provide water for many different purposes including defence, navigation, agriculture, fishing, mill-power and industry.

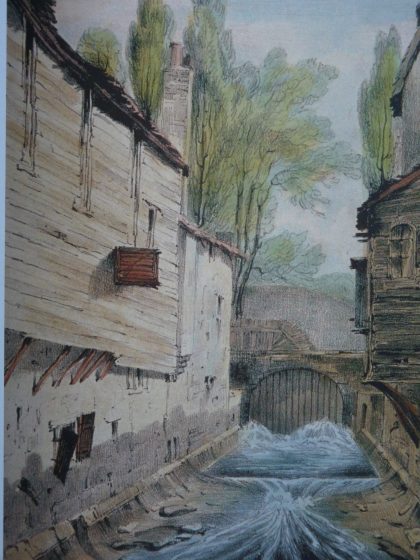

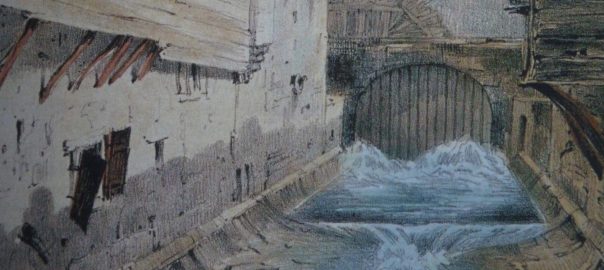

The book paints a picture of great changes overwhelming the rural landscape as London became an industrial metropolis. Clear bubbling streams and rivers, with numerous wells serving local communities, were replaced by urban squalor. As the city grew the rivers were progressively covered over and converted to subterranean conduits, lost from view. Out of view, out of mind. With the impact of industrialisation and rapid population growth the rivers became sewers. What had been some of London’s greatest assets were allowed to become so polluted that they became a major hazard to public health. Abuse of the rivers was one of the greatest failures in London’s evolution as a great metropolis.

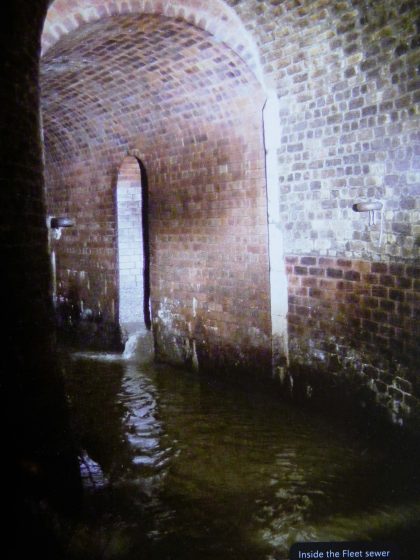

Creation of the great Victorian sewer system for London by Joseph Bazalgette in the 1860s was seen as a great success and his system of building sewers along the contours to intercept the natural drainage pattern was copied across the world. But most of the lost rivers of London are still there today. The book brings us right up to date with a discussion of problems associated with increased frequency of severe rainfall events, almost certainly due to climate change, when localized severe flooding overwhelms the so called “combined-sewers”, resulting in discharge of raw sewage into the River Thames. We learn that a massive new sewer, the Thames Tideway Tunnel, is currently being constructed to cope with these new conditions. It will be 25 km long running mostly under the tidal section of the River Thames through central London. The tunnel has a diameter of 7.2m, and is designed to provide capture, storage and conveyance of almost all the combined raw sewage and rainwater discharges that currently overflow into the river.

The Lost Rivers of London looks ahead and sees prospects for bringing back some of the hidden rivers. This has already been achieved for sections of small tributaries south of the Thames. Barton and Myers argue that it would be possible to do the same, even in the centre of London. The key to success of such a scheme is the fact that several of the lost rivers were naturally fed from unpolluted springs and streams on Hampstead Heath. At present this water is diverted straight into the local sewage system; a complete waste of a valuable asset. The authors suggest that this water could be channeled by gravity through a new pipeline into central London where it would certainly be possible to recreate short clean stretches on the courses of the Fleet, Tyburn, Westbourne and Walbrook in the very heart of the city. Now there’s a vision; the Fleet flowing again through the capital as a sparkling stream! This book is a must for anyone dealing with urban planning and design, not only in post-industrial cities, the lessons are just as valid in new cities today.

The Lost Rivers of London looks ahead and sees prospects for bringing back some of the hidden rivers. This has already been achieved for sections of small tributaries south of the Thames. Barton and Myers argue that it would be possible to do the same, even in the centre of London. The key to success of such a scheme is the fact that several of the lost rivers were naturally fed from unpolluted springs and streams on Hampstead Heath. At present this water is diverted straight into the local sewage system; a complete waste of a valuable asset. The authors suggest that this water could be channeled by gravity through a new pipeline into central London where it would certainly be possible to recreate short clean stretches on the courses of the Fleet, Tyburn, Westbourne and Walbrook in the very heart of the city. Now there’s a vision; the Fleet flowing again through the capital as a sparkling stream! This book is a must for anyone dealing with urban planning and design, not only in post-industrial cities, the lessons are just as valid in new cities today.

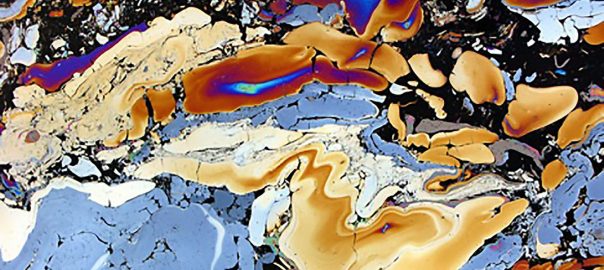

London’s Lost Rivers, by Paul Talling, is a more lighthearted take on the subject, choosing many of the oddities that are the legacy of the lost rivers. Examples include the sewage lamp nicknamed Iron Lily on Carting Lane in the West End, which was designed to burn off sewage smells from below, and the “stink pipe” performing a similar function at Stamford Brook. Other memorable features are the remains of numerous wells that once dotted the banks of the Fleet River and now grace street corners in Hampstead and Camden. It is a photojournalist’s book that provides a quick guide to London’s waterways that have disappeared, including docks, wharfs, canals and other man-made features that have little to do with lost rivers. But the sections dealing with the rivers provide an interesting perspective on the story, with magnificent photos such as the vast brick lined chambers of the Fleet Sewer built 160 years ago. The photo on page 41 says it all.

Paul Talling suggests that perhaps the most surprising thing about the hidden waterways is not that they have virtually disappeared into obscurity, but that there are so many of them. He points out that London is riddled with watery relics and clues to the past. There is abundant evidence if you know what you are looking for. His book provides an inspirational resource for schools, local historians, artists, poets, and even tourist guides. It’s a good size too; something that fits in the pocket whilst you explore the city.

Both books have a photo of the River Westbourne in its iron tube where it crosses the platforms above the underground line at Sloane Square station. How many travellers, I wonder, are aware that they have a river flowing over their heads? For me it’s one of the wonders of London.

David Goode

Bath

To buy the book, click on the images below. Some of the proceeds return to TNOC.

An excellent review! London is a great city full of charm and surprises. I will read one, possibly both, of these books. Allowing the spring fed rivers to flow naturally would also bring back wildlife and improve the quality of life immensely.