Global warming and misuse of water resources are increasingly leaving dry riverbeds in their wake. Now designers are looking for ways to safely create vital public spaces out of these open spaces while also preserving their historic hydrologic function.

In most arid regions of the world cities are growing and rivers are running dry. While rapid urbanisation has left little room for creating new public open spaces, could urban riverbeds that remain dry for an extended period of time provide potentials for new types of public parks?

Dryland settlements were historically established along flowing rivers (e.g. Mesopotamia (Tigris and Euphrates), and Egypt (Nile)), where freshwater bodies sustained the communities for centuries. But this is changing. With global warming, population growth and human-induced changes to water resources, the number of drying urban rivers has increased. Currently, drylands, including arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid regions, occupy 41.3 percent of the globe’s land area and support more than 2.1 billion of the world’s population.

It is unsettling to know that a number of permanently flowing rivers around the world including the Indus (Pakistan), Ganges (India), Amu Darya (Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan), Murray (Australia), Colorado (United States of America), Tagus (Spain) and Nile (Egypt) are now discharging very little, or no water to the sea for months during the year. Most of these rivers passing through old settlements and ancient cities, used to be the lifeline of the citizens.

A representative example of a drying urban river is the Zayandeh Roud in Isfahan, Iran. Literally meaning the “life-giving river”, Zayandeh Roud was one of the largest rivers in central Iran and a major source of water for the country. Many have memories sitting next to the flowing water, watching the glimmering lights reflecting from the Khajoo Bridge on the water surface, or picnicking in green parklands adjacent to the water edge in the midst of the city. Since the early 2010s, the lower segment of the river basin has dried out due to reduced rainfall, mismanagement and overuse of groundwater and surface water resources.

Zayandeh Roud has turned into a scar on the face of the city. Visitors can now walk and play inside the fractured dry riverbed. Some even have picnics next to the remaining waterholes where spontaneous vegetation grows, resembling oases in a desert.

The absence of water has created a different aesthetics; a landscape that reminds us of our drying climate. Meanwhile, it has also provided new and unique recreational opportunities; a meeting place for the inhabitants. The spasmodic flow of water has created a place of isolation and re-connection; when water flows, it re-connects the isolated living ecosystems adjacent to the riversides, and when dry it connects the inhabitants to the isolated riverbed. The river has become a contested space between natural flows and human activities.

Learning from arid Middle East

A closer look at some other arid cities in the Middle East shows that dry riverbeds were informally used as social spaces in the past. Wadis (the Arabic word for river valleys in drylands), acted as oases suitable for settlements and natural drainage systems for seasonal floods. They provided underground water resources, connector routes, sources of food, and shaded areas for nearby inhabitants.

Socially, the wadis had important cultural functions. In Muscat, Oman, for example, before the growth of the city as an expanding metropolis, the wadis and the riparian vegetation provided the nearby inhabitants a refuge from the hot summer weather. They were used as gathering spaces for families, tribes and villagers, by creating a microclimate of fresh and moist air with cooling effects of land-sea circulation.

Nowadays, dry riverbeds in urban areas are often composed of waste, gravel and dust, used as car parks and roads, and perceived as dumping grounds. They are over-engineered with altered morphologies, locked in concrete, or buried underground for fear of flooding and exposing the citizens to pollution accumulated over years of neglect. This has resulted in the deterioration of their natural ecology, and their disconnection from the urban context.

However, there seem to be changes in the making.

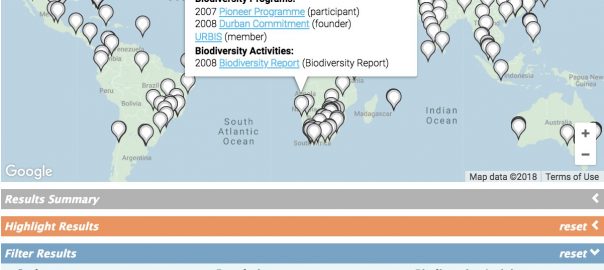

Our research shows that the role of wadis in the Middle East is shifting from junkyards to public parks, with a number of projects emerging to restore their natural and cultural values and reconnect them to urban life.

A new type of public open space in drylands?

An investigation into a number of wadi projects in the Middle East reveals that these void spaces can be transformed into public parks that provide new outlooks and forms of recreation.

The restoration of Wadi Hanifah in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, provides an example of recognising the opportunities for creating recreational uses along and inside the undeveloped riverbed when dry, while restoring ecological processes through revegetation and naturalisation. Designed by Canadian Landscape Architects, Moriyama and Teshima Planners, and UK based engineers from Buro Happold, the new walking trails and picnic areas proposed along and inside the dry segment of the wadi has created a new type of public open space; a large linear thin park previously unknown to the citizens.

Similarly, a number of wadi park projects have been commissioned in Muscat, Oman, where international designers were asked to create safe access to the wadi beds, and provide walking promenades, green spaces, playgrounds, and sport fields for users to reconnect them with these underutilized spaces.

Wadi Azeiba, designed by Atelier Jacqueline Osty & Associés, is the first completed wadi park project in Muscat. Field observations showed that the newly created park has successfully encouraged many nearby residents, particularly women, to walk more and interact with their neighbours, while their kids play in the open areas.

The wadi park acts as a hybrid space, which can be flooded when it rains, and transformed into a public park when it’s dry. However, questions of safety persist in the use of these dry riverbeds, which are at risk of flash flooding and turning into giant flood drains.

In the design of the Wadi Adai pedestrian bridge in Muscat, the Norwegian landscape designers, Snøhetta, took a creative approach to tackle safety issues. The descending ramp designed in the middle of the new pedestrian bridge, enables access to the dry wadi bed, while providing an option for quick evacuation from the wadi bed in times of sudden flash flooding, minimising the risks to users. With minimal design interventions and keeping the wadi bed free from building development, the designers aimed to retain the wadi’s hydrological function.

Looking forward

Can these projects provide a model for the transformation of other drying urban rivers into spaces of public use? Can these models be replicated in other cities? And what are the long-term impacts of this transformation on the rivers’ ecosystem, the local ecology and public life? These are important questions that require longitudinal studies of the ecological and social impacts of these new spaces. A data-driven design approach is required to ensure the solutions are responsive to the specific hydro-ecological and cultural characteristics of the context. This needs a multidisciplinary approach to design, where designers work closely with engineers, hydrologists and ecologists, as well as the local communities to understand how these transformations can achieve best performative outcomes.

Nevertheless, it is clear that with the advent of global warming and the number of urban rivers drying up, it is time we think about how to turn these scars into living spaces.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Dr Margaret Grose and Dr Jillian Walliss at the University of Melbourne for their support, help and guidance during this research.

Sareh Moosavi

Melbourne

Leave a Reply