In the weeks prior to the writing of this article, the city of Bengaluru was reeling under the onslaught of torrential rainfall, the likes of which it had not witnessed in decades. Effects of this downpour were felt in many ways—flash floods in several parts of the city, trees uprooted, lives lost, and gnarly traffic standstills. Viral visuals also surfaced showing the city’s main bus station, its prominent indoor stadium, and several other parts of the city knee deep in water. Several lakes breached their banks, while minor rivers like the Vrishabhavati, which have not held water within city limits for decades, came back to life.

It was also this rain that made people realize the faulty infrastructural planning of the city. Images of flyovers draining floodwaters into roads below like mini waterfalls, further contributing to floods, went viral in several circles (Image 1). Reports surfaced of citizens unable to go about their daily lives owing to rising water levels inside homes, and forced to explore outside the box ideas to combat these issues. One woman invested in a rowboat to navigate floodwaters (in land locked Bengaluru!) and ferry her children and those of her neighbours to their after-school tutoring.

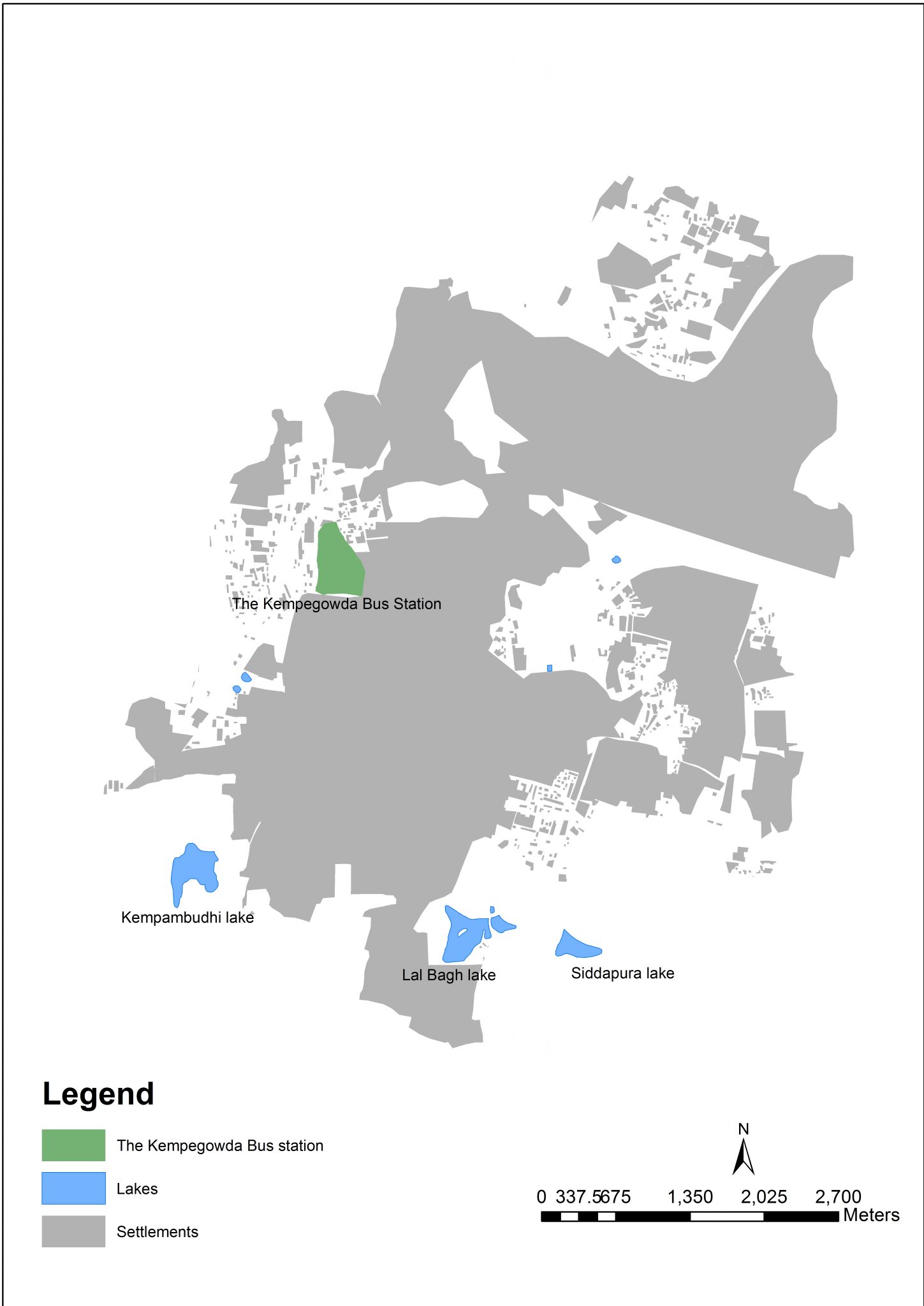

In addition to human suffering and infrastructural challenges, these events have another common thread running through them—that of a vanished waterscape brought to life in unexpected ways when nature decided to pay a call. The city’s present struggles with water are linked to its past, when the intimate relationship between the urban landscape and the waterscape was manipulated over several centuries, leading to its eventual loss. Flash floods, such as Bengaluru recently witnessed, jog memories and nostalgia surrounding Bengaluru’s lost lakes, channels, and streams. Several areas that were flooded in these rains were—for obvious reasons—locations of former lakebeds, storm water channels, and lake wetlands. The Kanteerava Stadium (formerly Sampangi lake), Majestic bus terminus (formerly Dharmambudhi lake), National Games Village (formerly Koramangala tank) and several others were recalled by popular media and cited as examples of bad urban planning by civic bodies.

Why did flooding at such a scale occur in a land locked city that is geographically prone to aridity and does not have a major river flowing through it? The answer to these questions requires one to revisit the city’s past. Early settlers and rulers, recognizing the geophysical constraints imposed by Bengaluru’s topography, exploited natural depressions in the land to engineer a series of networked, cascading water bodies connected by numerous channels. Filled seasonally by monsoon rainfall, water from one lake would overflow into the next across gradients of elevation, creating a flowing waterscape that met the water requirements of its early inhabitants. Water thus harvested and stored was supplemented through massive open wells that tapped into shallow aquifers recharged by lakes, thus ensuring further water security. Why and how did this all-important waterscape disappear across the centuries? Moreover, what does this mean for contemporary urban planning?

Any visitor to Bengaluru city traveling either by train or by bus cannot miss the sprawling Kempegowda bus station, the city’s central bus terminus. The area welcomes visitors and residents with a strong flavour of old Bengaluru—narrow streets, with colourful shops selling all manners of clothes, cheap plastic toys, bangles, vegetables, fruits, and flowers; traditional musical instruments, and old-style homes, juxtaposed to create a cacophony of noise and colour in this space. This is what remains of the Pete: the agricultural and industrial hub of colonial Bengaluru, which was separated from the anglicized cantonment, complete with parks, boulevards, and bungalows. Dharmambudhi lake in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, together with three other minor water bodies in the vicinity served to meet the water requirements of the Pete through the diversion of lake water into strategically placed stone troughs that enabled the collection of water. Sluice gates around the lake also enabled the provision of water for agriculture. The banks of storm water channels were used for a variety of domestic activities including washing clothes, swimming, and bathing. Access to pasturage was, however, regulated through tenders and public auctions. A lake deity on the banks of the lake provided the cultural and spiritual connection to the water body and was worshipped through an annual boat festival.

Dharmambudhi was further connected by means of several manmade channels to several other lakes in the vicinity—the Millers tanks, Sankey tank, and the Sampangi tank being the most prominent. Of these many tanks, today, only the Sankey tank survives in a shrunken form. The channels connecting the Dharmambudhi to these other lakes proved to be a source of conflict and were instrumental in catalysing large-scale change to the lake system. Several channels from this lake were diverted into other water bodies or were closed up and built over for several decades before the effects of these activities were perceptible. The lake was considered to be in decline as far back as 1877, and this decline exacerbated conditions of famine in Bengaluru between the autumn of 1876 and March 1877. The main channels connecting this lake with the Sampangi lake (Image 2) were diverted to a newer lake up north (presumably the Sankey), thereby reducing the water flow to the Dharmambudhi. This diversion was meant to clear the way for new railway lines connecting the city. By the October of 1882, the lake had dried up completely, an event linked to a loss of water for farming, and inflation in the prices of food grain.

The effects of a disrupted channel system began to be felt in other lakes of this network by 1883, causing communities dependent on water for livelihoods such as horticulturists to rise up in revolt. Restoring the channel became an issue of contention between the Mysore kings and the British administrators. A number of technological solutions were proposed, ranging from restoration of the channel to digging a tunnel under the railway line to channel water. None of these proposals were however taken up. All this while, other channels connecting the lake were also disrupted for various purposes, further reducing the inflow of water into this lake and rendering it completely dry by 1892. The city started receiving piped water from distant sources by this time, rendering activities to restore the Dharmambudhi redundant. By 1935, most of the lake was completely dry (Image 3) and the land began to be utilized for a playground. One swampy marsh, where little water was left, was considered too dangerous to negotiate. As with other lakes in the city, the attention of planners was focused on making “use” of this land, by converting it into a playground or a school. Rallies for Indian independence, cattle fairs, exhibitions, and circuses were held on this land, transforming its identity.

Together with a strategic renaming of the landscape into Subhashnagar (in honour of an Indian freedom fighter) after Indian independence, the former waterscape was relegated to the realm of hazy memories, soon to die out and be replaced by others.

The present-day bus station (Image 4) was conceptualized and built on the land by the late 1980s—a brainchild of the then Chief Minister, who was inspired by bus terminals during his tour of New York. Today’s generation of inhabitants around the area, have few memories of its former existence as Dharmambudhi lake. Remnants of the past remain however: a portion of the sluice gate overwhelmed by roads and debris, a single storm water channel today transporting sewage (permeating the air with its unique stench) and flooding the landscape periodically, and temple of the former lake deity, who now occupies a rather privileged position in the middle of a busy road (Images 5 & 6). Otherwise, it is only during rains such as the one Bengaluru witnessed this autumn, when the bus terminal fills up with water that memories are jogged and one remembers the past.

The loss of connectivity in this waterscape resulted in the destruction of not just one but several lakes along the chain, which then began to be built over with malls, residential layouts, sports arenas, and other structures. The city expanded phenomenally, began to attract immigrants, and sourced water from a river (the Cauvery) almost 100 km away. Ecological memory persisted, however: the floodplains recalled their original functions despite being unrecognizable from the past, and water continued to flow along the elevation gradient and filled up naturally occurring depressions of the landscape in accordance with the engineering design of long ago.

The floods of 2017 serve as a stark reminder of this lost waterscape, occurring predominantly in converted beds of former lakes, or along channels converted long ago and the serious implications of destroying floodplain connectivity. Effects of such disruption are not limited to the famines and drought resulting from immediate disruption, but can manifest themselves centuries later, such as through the floods in Bengaluru. This ecological history provides potential lessons to upcoming cities of the global south that follow similar trajectories of urbanization, to be aware of the complexities of their waterscapes and plan cities accordingly. Cities need to focus efforts on not encroaching or otherwise destroying the floodplains, while at the same time investing efforts to sustain their existing water infrastructure. This even while sourcing water from elsewhere for meeting rising demands. This will ensure better urban flood mitigation strategies while also creating a secondary dependable water source for the city to fall back on, in case of adverse conditions. Planning strategies of this nature therefore necessarily needs looking to the past in order to create a more resilient and sustainable urban future.

Hita Unnikrishnan and Harini Nagendra

Bangalore

About the Writer:

Harini Nagendra

Harini Nagendra is a Professor of Sustainability at Azim Premji University, Bangalore, India. She uses social and ecological approaches to examine the factors shaping the sustainability of forests and cities in the south Asian context. Her books include “Cities and Canopies: Trees of Indian Cities” and "Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India's Cities" (Penguin India, 2023) (with Seema Mundoli), and “The Bangalore Detectives Club” historical mystery series set in 1920s colonial India.

About the Writer:

Hita Unnikrishnan

Dr. Hita Unnikrishnan is an Assistant Professor at The Institute for Global Sustainable Development, The University of Warwick. Hita’s research interests lie in the interface of urban ecology, systems thinking, resilience, urban environmental history, public health discourses, and urban political ecology as it relates to the evolution, governance, and management of common pool resources in cities of the global south.

Glad to hear this, Sahana. Best wishes, Harini

THANK YOU SIR .These are the great links which helped me out for my study.

Thanks Arun. These are great links. It is ironic indeed that we don’t teach high school students their local histories, but focus instead on a distant rulers and distant battles. A few years ago, the Pollution Control Board held a public event to raise awareness about the importance of lakes at the Kanteerava stadium – but none of the students who had been shanghaied into attending knew that the stadium was itself a lake. All this while they were listening to presentations and viewing exhibits on the importance of water. It is strange, but sadly not surprising that you don’t remember any of this being taught at school… we need to collectively work to change this in the coming years

The old lakes of Bengaluru have been such a fascination for me since a research project in my design class had me knocking on the doors of CES/IISc for more information and finding out about the history of Majestic bus stand and the realization that every waterbody is connected. Strangely I don’t recall this important concept being ever taught in school.

Two more maps to share for those interested:

– An interactive map of old tanks and streams of Bangalore (1920) by Gubbi labs https://gubbilabs.github.io/bengaluru-streams/

– A global map of rivers and streams with their flow directions from OpenStreetMap Project https://api.mapbox.com/styles/v1/planemad/cj8ul75i275p52rogvewe4xiu.html?fresh=true&title=true&access_token=pk.eyJ1IjoicGxhbmVtYWQiLCJhIjoiemdYSVVLRSJ9.g3lbg_eN0kztmsfIPxa9MQ#13.37/12.9714/77.5966