The end of Zika doesn’t begin with the eradication of a mosquito: it requires a systemic, intersectional analysis to help identify how social, economic, urban, health and other structures shape women’s lives, power, and their vulnerability to climate impacts and access to resources.

Almost exactly two years ago, South America was swept up in a public health crisis that affected hundreds of thousands of women across the continent. In Brazil, more than 2,600 children were born with the microcephaly and other health complications resulting from the viral infection Zika. Brazilians quickly became accustomed to the unfamiliar name of the disease, which spread fast across the North East of the country and across borders to Colombia and Venezuela. By February 2016, the World Health Organisation had declared the Zika epidemic a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC)—the fourth PHEIC it had made after the swine flu (2009), polio (2014), and ebola (2014). Zika, a mosquito-borne viral disease that emerged in South America in 2015, is carried by the mosquito Aedis aegypti and can also be transmitted sexually.

As someone who works with climate change adaptation, I was particularly struck by the climatic and systemic elements of the epidemic. In the North East of Brazil, the area most affected by Zika, droughts are not uncommon and are intensifying with climate change. Many households, particularly among the poor, store water to deal with shortages that result from inefficiencies in urban water supply. Struck by abnormally high temperatures in the region, the combination of heat, stored water, and poor urban infrastructure provided fertile breeding ground for mosquitoes. Studies published since the crisis have helped establish that the El Niño contributed to unusually high temperatures in the region and that climate change is a contributing factor to Zika.

Another element which affected me was the evident gender inequality that marked the health crisis. As a middle-class white woman living in São Paulo, I felt far removed from the Zika crisis despite the incessant national and international media coverage and messages of concern from my friends abroad. Even Olympic athletes were considering not coming to Brazil and made elaborate plans to protect themselves. I was not concerned with my exposure to Zika. I do not, however, live close to informal settlements or suffer from water shortages or poor urban development, and neither am I stuck in poverty.

Six percent of Brazil’s population—almost 12 million people—live in informal settlements known as favelas. Amongst this population of slum dwellers, roughly half, or 6 million people, are women. The gender disparity of the crisis is emphasised by the law professor Debora Diniz in her New York Times article: “Lost in the panic about Zika is an important fact: The epidemic mirrors the social inequality of Brazilian society. It is concentrated among young, poor, black and brown women, a vast majority of them living in the country’s least-developed regions.” Many of the urban regions affected by Zika lack basic public services, such as water supply or waste treatment. In 13 of the 27 state capital cities in Brazil, less than half the population has access to municipal with sewage collection services. On average, only 42 percent of cities have installed appropriate municipal sewage treatment services.

The most devastating impact of the Zika crisis was the impact on women’s human rights and the sheer lack of power, access to resources and information, and control they had over their bodies. In Brazil abortions are illegal; 20 percent of all pregnancies are in teenagers and half of pregnancies are unplanned. Access to family planning and reproductive information is limited. Throughout the Zika crisis, women infected with the virus were not granted abortions, and initial government response to the crisis focussed on advising women only to withhold from sex and delay pregnancy. The onus to prevent Zika or minimise risks of infecting was shouldered onto women.

As the crisis unfolded, I found myself trying to gather insights into how Zika affected women from public health, racial injustice, water security, climate change, gender inequality, abortion, urban development, and human rights perspectives. I developed a sense of urgency that the epidemic afforded us an opportunity to understand and gain insights into how potential climate change impacts in cities must be understood from a systemic and intersectional approach. Climate change impacts are distributed locally and unevenly in cities, both spatially and socially. Given projected urban growth and climate change, how can cities ensure their most vulnerable citizens are protected from and prepared for climate change? More importantly, how can cities account for the varying impacts on climate change across diverse groups of people, identities, and individuals?

Two years on, and there seems to a collective memory loss about Zika in Brazil. Many articles in Portuguese have appeared referring to the forgotten state of the women affected by Zika. Many women have been abondanoned by the fathers of their children with microcephaly, receive no government support to deal with rising healthcare costs, and are unable to effectively cope with caring for a child who has special needs and uphold a full-time job. Urban services such as public transportation is often limited, which means that mothers have to travel long distances to reach medical and support services. The burden to prevent, cope and recover from Zika thus lies with these women who live in informal housing, tend to be brown or black, and poor.

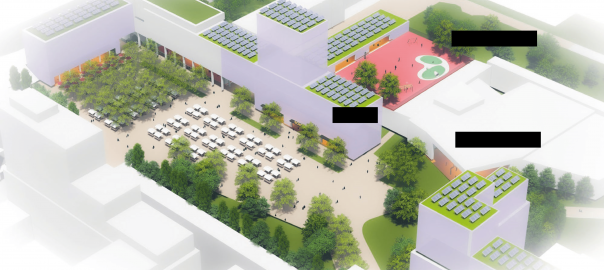

In the English-language world, the recent and excellent report “Neglected and Unprotected: The Impact of the Zika Outbreak on Women and Girls in Northeastern Brazil”, published in July by the Human Rights Watch, analyses the long-term impacts of the Zika epidemic on women, with far-reaching analysis that goes beyond climate change and gender inequality. For example, the report looks at how public healthcare, abortion laws, and urban development structure women’s lives and realities and therefore influence the impact that Zika had on them. To prevent and reduce the impacts from future outbreaks, the Human Rights Watch report makes technical recommendations that address public health emergency response, access to health information, education and awareness raising, child support, people’s rights to water security and sanitation, sexual and reproductive healthcare, decriminalisation of abortion, climate change adaptation policy, and urban development amongst others. In short, the end of Zika doesn’t begin with the eradication of a mosquito: it requires a systemic, intersectional analysis to help identify how social, economic, urban, health and other structures shape women’s lives, access to resources, power, and their vulnerability to climate impacts such as Zika. Such an analysis should inform appropriate urban planning.

The term intersectionality was coined by critical race theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw and is defined as “the interaction between gender, race and other categories of difference in individuals lives, social practices, institutional arrangements, and cultural ideologies and the outcomes of these intersections in terms of power.” Whilst Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality within the field of critical race theory, it serves as a relevant lense through which to analyse climate change impacts in cities. As researchers Anna Kaijser and Annica Kronsell point out, “since the effects of climate change are mediated through social, cultural, and economic structures and processes, the need for social analyses in relation to the issue has become more recognised”. Yet gender-responsive and intersectional analysis remain largely absent from urban climate change adaptation planning. Literature and research on climate resilience, in particular, has been critiqued for not addressing enough issues of power and inequality. For example, a study from 2015 analysed 123 papers and looked at how gender is incorporated into adaptation, resilience and vulnerability (ARV) studies published in the peer-reviewed literature. The research concludes that whilst gender is increasing in focus in ARV research, it is still marginal.

Adopting intersectional approaches can help reveal otherwise hidden information about groups of people or individuals that are useful for climate change adaptation planning and extreme weather events. Natalie Osborne notes that in disasters risk management research, for instance, intersectionality helped develop understanding that although vulnerability to extreme weather events is gendered, it is “also shaped by ability, family type, cultural/racial group, and class.” This type of knowledge can lead to more effective interventions to minimise vulnerability. As Osborne also writes in her paper ”

Intersectionality and Kyriarchy: a framework for approaching power and social justice in planning and climage change”, “there is a lot of data to suggest that today’s marginality is tomorrow’s vulnerability to the impacts of climate change and peak oil”.

Here are some practical questions developed by Matsuda that city managers should consider when working on urban adaptation planning:

“When I see something that looks sexist, I ask, ‘Where is the heterosexism in this?’ When I see smoething that looks homophobic, I ask, ‘Where is the class interests in this?”

Asking such questions can help internalise a method for analysis and planning that can generate more nuanced understandings of people’s vulnerability to climate change impacts.

At this given moment, cities in Brazil are being dramtically impacted by climate change-driven weather extremes, such as droughts and flooding. Currently, the country’s capital, Brasília, is going through a historical drought and households have been subjected to a water rationing scheme whereby two days a week water supply to households is limited. As cities prepare to build capacity to plan for and manage climate change impacts, this process should ensure it is accountable to individuals’ and groups’ different needs, life experiences, power, access to resources and vulnerability. The Zika epidemic demonstrates how particular groups of women are more exposed to the outbreak and long-term consequences due to a set of social norms, institutional arrangements and physical structures over which they have little control. With a better grasp of the realities that poor, black and brown young women face, urban planners could have better identified the need to reduce the risks of mosquito proliferation and developed longe-term support structures to help mothers care for their children with microcephaly.

City managers and planners need to internalise and promote awareness of intersecting structures to identify particular needs and vulnerabilities that aren’t at first obvious and develop plans accordingly. Solutions to climate change will come through better governance, planning, and efforts to increase participation and social inclusion. It is crucial to derive lessons from the Zika epidemic that could benefit and improve urban climate change planning and adaptation in Brazil.

Katerina Elias

São Paulo

Leave a Reply