Managing the tension between biodiversity and livability on Melbourne’s volcanic plains grasslands is possible, using scientific evidence to support tree selection and habitat design, balanced with an understanding of the biological, social and cultural needs of people.

What to do when biodiversity ideals conflict with livability imperatives for a city? A fascinating example of this tension is the western suburbs of Melbourne, the capital of Victoria, Australia. The greater metropolitan area of Melbourne lies on several bioregions. Most of the northern, southern, and eastern suburbs lie on the Gippsland Plain and Highlands-Southern Fall bioregions, with small areas within the Otway Plain, Central Victorian Uplands, and Highlands-Northern Fall. In contrast, the western suburbs lie on the Victorian Volcanic Plain.

The vegetation communities of these bioregions vary greatly, and therein lies the tension: the indigenous landscapes of the Victorian Volcanic Plain are largely treeless, predominantly grasslands. Yet, livability dictates the inclusion of a tree canopy for shade, aesthetic value, sustainable water management, connection with nature, etc. Nevertheless, requirements for biodiversity can be reconciled with requirements for livability. It just requires a flexible approach and evidence-based design.

The Western Volcanic Plain extends as a belt 100 km wide from the Yarra River where it passes through the inner-eastern suburbs of Melbourne to 350 km west. With an area of approximately 20,000 square kilometers, it is the third largest volcanic plain in the world. There are many ecological vegetation classes (EVC) in this bioregion, some of which include trees. Overwhelmingly, though, it is plains grassland that is thought to have covered most of the area now being settled to the west of Melbourne. It is to this EVC that environmental officers would look when establishing public open space.

Victoria has embraced the need for sustainable and resilient development, which must include addressing urban heat island and sustainable water management issues. Inevitably, trees are an important element in these approaches. There are three tiers of government in Australia and all have policies that affect biodiversity in our cities and the presence of trees.

At the national level, Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 is the Australian Government’s key piece of environmental legislation, supported by a set of regulations. Commencing in July 2000, the EPBC Act provides the framework for a national scheme of biodiversity conservation (as well as environment and heritage protection). Responsibilities are split between the national and state and local governments, depending on the level of environmental significance, i.e., national, state or local.

The EPBC Act enables the Australian Government to join with the States and Territories in providing a truly national scheme of environment and heritage protection and biodiversity conservation. The EPBC Act focuses Australian Government interests on the protection of matters of national environmental significance, with the States and Territories having responsibility for matters of state and local significance. Amongst the objectives of the legislation particularly relevant to cities are the conservation of Australian biodiversity and promotion of ecologically sustainable development through the conservation of natural resources.

At the State level, Victoria has developed a plan—Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037—“to stop the decline of our native plants and animals and improve our natural environment so it is healthy, valued and actively cared for”. The plan addresses biodiversity on private land, on public land and in conservation reserves. Working with the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act and native vegetation clearing regulations, the plan provides a mechanism to protect and manage Victoria’s biodiversity. Relevant aspects of the plan to protect biodiversity in Victoria’s cities relate to more effective management of threats “across the landscape to ensure that species and ecosystems are conserved, and to give biodiversity the best chance to adapt to the effects of climate change and human population growth”. Importantly, the plan notes that the system of conservation reserves should be reviewed periodically “to ensure that permanent protection of biodiversity is as effective as possible under changing climate conditions and land uses”.

There are 79 local councils in Victoria, of which 31 lie within greater Melbourne. Each council operates independently. An elected group of councilors sets the agenda for the municipality, and professional members of staff fulfill various roles to achieve the council’s objectives. Although biodiversity objectives of local councils must align with the state’s objectives, each council can set its own priorities. In an interesting study, Peter Morison found that commitment of local Melbourne municipalities to water-sensitive urban design (WSUD) varied with “environmental values, demographic and socio-economic status, local organized environmentalism, municipal environmental messages, and intergovernmental disposition” (p. 83). Commitment to WSUD was greatest in those local councils closest to the coast or with more than 50 percent cover with natural vegetation. It would not be surprising to find that support for biodiversity conservation varied similarly. Thus, local councils might be expected to differ in their policies on biodiversity and their management of it in response to the demand for more livable cities as populations grow and the suburban fringe expands.

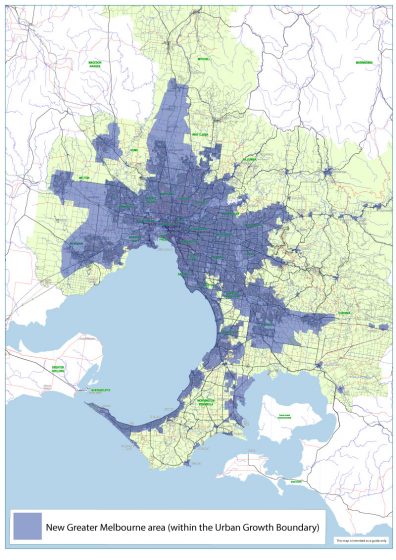

The Victorian government has established an Urban Growth Boundary to manage the expansion of greater Melbourne. The intent is to direct Melbourne’s growth toward land that can be readily supplied with infrastructure and services and to protect valuable peri-urban land and environmental features from urban development. There are many threatened ecological communities in greater Melbourne, but the natural temperate grassland and grassy eucalypt woodland on the Victorian Volcanic Plains to the west of Melbourne are especially pressured by urban development.

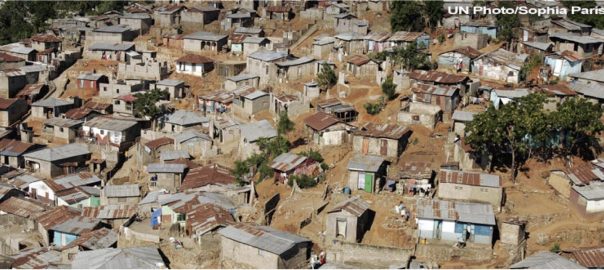

Each of the local councils responsible for management of biodiversity within their municipalities has biodiversity strategies and/or plans, recognizing that “the conservation of native biodiversity in close proximity to a large and dense human population is a challenge that relies on planning and active management” (p. 13). These councils also recognize that open space available for biodiversity management includes not just remnant native habitat but also parks and gardens, recreational areas and constructed landscapes. Thus, many councils have developed urban forest strategies and broader environmental strategies. Ideally, these strategies and plans, at different scales and with different focuses, are complementary and mutually supportive.

Let’s look at the approach of one council in particular, out on the western edge of Melbourne’s urban growth boundary. This area is experiencing rapid population growth, accompanied by development of residential estates. The challenge is to conserve the remnant biodiversity of the volcanic plains grasslands and yet create livable sustainable communities. Wyndham Council has developed a Biodiversity Policy 2014, an Environment and Sustainability Strategy 2016-2040, and a (draft) City Forest and Habitat Strategy 2018-2040, amongst others. Within a framework established by the Environment and Sustainability Strategy, the Biodiversity Policy commits the council “to:

- Enhance: Local flora, fauna and ecosystems make an important contribution to life in our community. Wyndham City is committed to ongoing, high quality management and improvement of its own natural assets.

- Plan: Wyndham City has a responsibility to lead by example and influence the protection of biodiversity on behalf of the community, with a focus on strategic conservation gains in planning and decision making and long term resilience of biodiversity in a changing environment and climate.

- Educate: An educated and engaged community will value, support and protect the conservation of local biodiversity.

- Partner: Sustained partnerships will maximise conservation outcomes within Wyndham and the wider region.

- Monitor, Learn and Adapt: Monitoring, Evaluation, Reporting and Improvement (MERI) is integral to ensure that management regimes are effective and benefiting biodiversity.”

The (draft) City Forest and Habitat Strategy then provides specific actions to ensure that “the right tree in the right place” is achieved. To manage the tension between biodiversity objectives associated with the largely treeless plains grassland and the desire to increase canopy cover in the municipality, tree selection criteria varies with location. For example, locally indigenous trees should be used in streets, depending on street character and habitat zones. If the median strip is wide enough, such trees should be chosen for attributes that will provide habitat for local wildlife. Suitable indigenous trees are limited, though. So, native Victorian trees might be used instead. Unfortunately, suitable native Victorian trees are also limited, in which case native Australian trees are suggested, with flowering trees preferred as a food source in habitat zones and invasive species to be avoided. Use of exotic (overseas) trees is to be limited in habitat zones, again with a preference for trees with flowers. In contrast, along rural roads, trees are to be selected to match existing plantings. Grassland quality along roads should be assessed before planting trees, which should be spaced widely to reduce their impact on the adjacent native grasslands. Trees along drainage lines and general reserves should be selected from indigenous and native Victorian species where the trees can contribute to a contiguous habitat. Native Australian trees should be used in such locations to match existing character and to create habitat. Exotic trees should only be used to maintain existing character. In natural waterways or wetlands, indigenous trees should be used in most cases. In constructed parks and around ornamental waterbodies, park character determines the choice of tree species; if exotic trees are to be used, flowering forms are preferred, to contribute to habitat. Wyndham Council aims to increase the tree canopy cover in its open space, excluding grasslands, from 4.3 percent in 2017 to 35 percent in 2040.

In addition, BOBITS are proposed. These “bits of bush in the suburbs” would provide patches of habitat within a matrix of residential development. Ideally, such patches would also form corridors for wildlife movement between patches.

In choosing the right tree for the right place, aesthetic considerations are less important than the ability of the tree to grow in the location and to provide the most benefits for the community. Life expectancy and maintenance requirements are also important, as is choosing a tree with the largest canopy possible.

In applying these selection criteria, Wyndham Council is practising the principles identified by American landscape architects Garrett Eckbo, Dan Kiley and James Rose, in 1939 and 1940 in three articles titled “Landscape design in the urban environment”, “Landscape design in the rural environment” and “Landscape design in the primeval environment”, in the Architectural Record. Their message can be summed up quite easily: any place should be designed for the needs of its primary inhabitants. In their words: “The design principles underlying the planning of the urban, rural, and primeval environments are identical: use of the best available means to provide for the specific needs of the specific inhabitants; this results in specific forms”. Thus, urban areas should be designed bearing in mind primarily the needs of its human residents. However, Eckbo, Kiley and Rose continue: “None of these environments stands alone. Every factor in one has its definite influence on the inhabitants of the other, and the necessity of establishing an equilibrium emerges. To be in harmony with the natural forces of renewal and exhaustion, this equilibrium must be dynamic, constantly changing and balancing within the complete environment. It is this fact that makes arbitrary design sterile and meaningless—a negation of science. The real problem is the redesign of man’s environments, making them flexible in use, adaptable in form, economical in effort and productive in bringing to individuals an enlarged horizon of cultural, scientific, and social integrity”.

Managing the tension between biodiversity and livability on the volcanic plains grasslands is possible, using scientific evidence to support tree selection and habitat design, balanced with an understanding of the biological, social and cultural needs of the place’s primary inhabitants, the humans. Wyndham Council has demonstrated how balance can be achieved between environmental preferences for indigenous landscapes and social preferences for treed landscapes in our suburbs. In contrast, primeval landscapes, such as remnant grasslands, should be managed for their primary inhabitants, the indigenous flora and fauna. This doesn’t mean that such grasslands have no place in suburban landscapes, nor that they do not contribute to livability, but that is a topic for another post.

Meredith Dobbie

Victoria

Leave a Reply