Cleanup of Great Lakes pollution hot spots has not been easy, and required networks focused on gathering stakeholders, coordinating efforts, and ensuring that the results promote the public interest. Even with the compelling case of the Great Lakes being a continentally- and globally-significant natural resource, it has proven incredibly challenging. For those working in the trenches of ecosystem-based and watershed management, it is best described as a challenging puzzle requiring a marathoner’s discipline and perseverance.

The Great Lakes are freshwater seas that contain nearly one-fifth of the standing freshwater on the Earth’s surface. They are also a shared resource between Canada and the United States. Approximately 34 million people in the U.S. and Canada live in the Great Lakes Basin. Both countries depend on the Great Lakes for drinking water, transportation, economic opportunities, power, and recreation. For example, 48 million people in the U.S. and Canada get their drinking water from the Great Lakes. Cargo shipments on the Great Lakes St. Lawrence Seaway system generate $US 34.6 billion of economic activity and 227,000 jobs in Canada and the U.S. The Great Lakes directly generate more than 1.5 million jobs and $60 billion in wages annually and provide the backbone for a $5 trillion regional economy that would be one of the largest in the world if it stood alone as a country. Recreation on the Great Lakes—including boating, hunting, fishing, and birding opportunities—generates more than $52 billion annually for the region. Commercial, recreational, and tribal fisheries in the Great Lakes alone are collectively valued at more than $7 billion annually and support more than 75,000 jobs.

Given the level of population density, and commercial and industrial development, it is not surprising there have been considerable environmental impacts. From extirpation of beaver during the fur trade, to sedimentation and loss of habitat during the logging era, to waterborne disease epidemics in the early 1900s, to cultural eutrophication starting in the 1950s and continuing to the present, to toxic contamination as a result of the industrial revolution, to the introduction of exotic species, and climate change in more recent years, the Great Lakes have experienced substantial human use and abuse.

Canada and the U.S. have worked together for over a century to resolve problems along their common border. For example, the 1909 U.S.-Canada Boundary Waters Treaty provides the principles and mechanisms for preventing and resolving disputes concerning water quantity and quality along the entire border. Far ahead of its time, the Boundary Waters Treaty also states that waters shall not be polluted on either side of the boundary to the injury of health or property on the other side. As such, this treaty is often described as the world’s first environmental agreement. The International Joint Commission (IJC) was established under the Boundary Waters Treaty to foster binational cooperation in resolving trans-boundary environmental issues.

The IJC is an independent and objective advisor to the U.S. and Canada, and works for the common good of both countries in preventing and resolving any disputes regarding boundary water management issues. The IJC uses experts, serving in their personal and professional capacities, to undertake independent fact-finding and to provide independent advice for problem resolution. Its processes have compiled agreed-upon and trusted scientific and socioeconomic data, and have interpreted these data in a public fashion to build broad-based understanding and support for action. More recently, IJC processes have fostered use of a systematic and comprehensive ecosystem approach.

The Canada-U.S. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement was initially signed in 1972 and revised in 1978, 1987, and 2012. As such, this agreement is described as an evolving instrument for ecosystem-based management. It represents a commitment between the U.S. and Canada to restore and protect the waters of the Great Lakes and provides a framework for identifying binational priorities and implementing actions that improve water quality and ecosystem health. Canada and the U.S. are responsible for final decision-making under the agreement and for the involvement and participation of state and provincial governments, tribal governments, and other stakeholders.

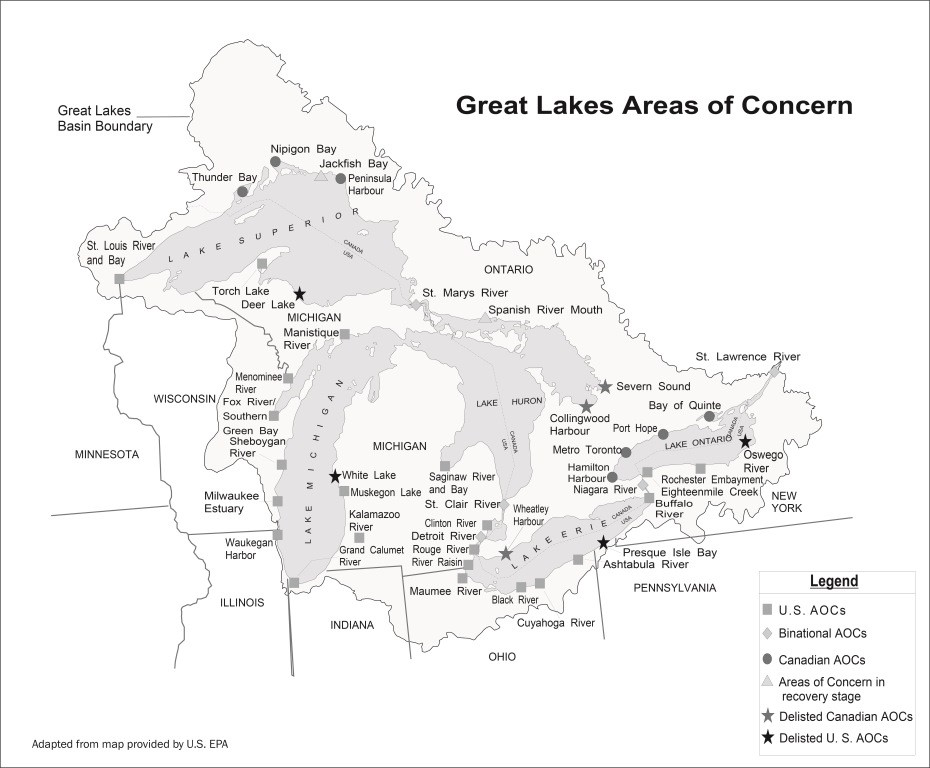

Since 1973, the IJC’s Great Lakes Water Quality Board, the principal advisor to the IJC on matters about the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, has periodically assessed the state of the Great Lakes. As part of these assessments, the Great Lakes Water Quality Board identified specific harbors, embayments, river mouths, and connecting channels where one of more jurisdictional standards or general or specific water quality objectives of the agreement were not being met. Initially termed “problem areas”, they were later called “Area(s) of Concern” (AOCs).

The list of AOCs changed over time due to the implementation of remedial and preventive programs and improvements in water quality, and the emergence of new problems and/or reinterpretation of the significance of earlier reports. The major problems identified also changed in response to the evolution of scientific understanding of ecosystem problems, improved ability to detect and measure problems, and progress in environmental cleanup and ecological restoration.

Despite progress in abating bacterial and phosphorus pollution in many AOCs, the Great Lakes Water Quality Board reported in 1985 that progress had been stalled in 42 AOCs where general or specific objectives of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement were not being met. This failure had caused or had likely caused impairment of beneficial use or of the area’s ability to support aquatic life. A 43rd AOC was identified in 1991 (i.e., Presque Isle Bay, Erie, Pennsylvania). Impairment of beneficial use means a change in the chemical, physical, or biological integrity of the Great Lakes ecosystem sufficient to cause any of the following:

- Restrictions of fish and wildlife consumption;

- Tainting of fish and wildlife flavor;

- Degradation of fish and wildlife populations;

- Fish tumors or other deformities;

- Bird or animal deformities or reproductive problems;

- Degradation of benthos;

- Restrictions on dredging activities;

- Eutrophication or undesirable algae;

- Restrictions on drinking water consumption, or taste and odor problems;

- Beach closings;

- Degradation of aesthetics;

- Added costs to agriculture or industry;

- Degradation of phytoplankton or zooplankton populations; or

- Loss of fish and wildlife habitat.

As a result of the recommendation of the Great Lakes Water Quality Board, the eight Great Lakes states and the Province of Ontario, with support from the federal governments of the U.S. and Canada, committed in 1985 to developing and implementing a remedial action plan (RAP) to restore all beneficial uses in each AOC within their political boundaries. This RAP commitment was then codified in the 1987 Protocol to the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.

Each RAP identified the use impairments and causes, the remedial and preventive actions needed to restore use impairments, the agencies or organizations responsible for implementing the actions, and the timeframe for implementation to increase accountability. Further, RAPs adopted an ecosystem approach that accounts for the interrelationships among air, water, land, and all living things, including humans, and involves all user groups in management. RAPs have been implemented in an adaptive management fashion where assessments are made, priorities set, and actions taken in an iterative fashion for continuous improvement.

Since the commitment to RAPs in 1985, it is fair to say that there were 43 locally-designed ecosystem approaches to use restoration in AOCs (Figure 1). In total, as of 2016, seven AOCs have been delisted, two AOCs have been designated as Areas of Recovery, 18 AOCs have implemented all remedial actions deemed necessary for use restoration, 65 of 146 known use impairments identified in Canadian AOCs have been eliminated, and 62 of 255 known use impairments in U.S. AOCs have been eliminated. Although much has been accomplished, much remains to be done to restore all impaired uses and delist all AOCs.

Overall, it is fair to say that progress has been challenging and slow. However, it took over a century to create these problems, and it should not be surprising that restoration would be a long-term process. In such urban, environmental restoration work, benefits assessments have proven to be an important tool to help make the case for restoration and requisite funding, sustain momentum over decades, and manifest return on investment. Further, such economic benefits studies have attracted considerable backing in support of sustaining seed funding from governments to finish the job of cleaning up AOCs that has helped leverage money. Selected examples of benefits assessments are presented below.

Detroit River

During the 1960s, the Detroit River was one of the most polluted rivers in the Great Lakes Basin. Considerable remediation has occurred in and along the Detroit River resulting in substantial ecological recovery, including the return of bald eagles, peregrine falcons, osprey, lake sturgeon, lake whitefish, walleye, mayflies, wild celery, and more. This restoration has laid the foundation for the revitalization of the riverfront with the building of the Detroit RiverWalk for all (Figure 2). The Detroit RiverWalk is now one of the largest, by scale (5.5 miles in downtown Detroit), urban waterfront redevelopment projects in the United States, resulting in over $1 billion in economic benefits in the first ten years. The Detroit RiverWalk has utilized democratic design to achieve benefits for all. The Detroit RiverWalk has also helped reconnect citizens to continentally-significant natural resources and has helped Detroit become an urban getaway for outdoor recreation.

Hamilton Harbour

Hamilton Harbour lies at the western tip of Lake Ontario near the cities of Hamilton and Burlington, Ontario, Canada. Hamilton is considered the “steel capital” of Canada. Contaminated sediments are a major problem. Located in the harbor is Randle Reef, a 148-acre contaminated sediment hotspot where sediment remediation is underway (Figure 3). The cost of sediment remediation of Randle Reef is $138.9-million. Local businesses are projected to realize about $600 million in gross accumulated benefits with full sediment remediation. Likewise, recreational users are projected to realize about $500 million in gross accumulated benefits with full remediation.

Figure 3. Sediment remediation underway at Randle Reef in Hamilton Harbour, Ontario, Canada. Photo: Environment and Climate Change Canada

Muskegon Lake

Muskegon Lake is an over 4,000-acre inland coastal lake along the eastern shoreline of Lake Michigan. It has over a 100-year history of anthropogenic impacts from lumbering, industry, and urbanization. Considerable restoration has occurred, including remediation of contaminated sediment and restoration of habitats. A considerable portion of the shoreline that was once natural wetlands had been filled in with foundry materials. A $10 million shoreline restoration project was implemented to soften the shoreline and restore wetland habitats. An economic benefits study has shown that this $10 million shoreline restoration project on Muskegon Lake will generate more than $66 million in economic benefits, resulting in a 6-to-1 return on investment.

Kinnickinnic River

The Milwaukee Estuary in Wisconsin was designated an AOC primarily due to contaminated sediments and loss of habitat. In 2009, a Great Lakes Legacy Act project dredged a 0.4-mile section of the Kinnickinnic River on the south side of Milwaukee. In total, 158,000 yd3 of contaminated sediment were removed and disposed at a cost of $22.4 million. Milwaukee literally transformed this former toxic hot spot into a waterfront destination for businesses, recreation, and tourism. Direct benefits to Milwaukee from this sediment remediation included: adding more than 100 jobs; supporting more than $1 million in wages for new workers; increasing revenues along the Kinnickinnic River, realizing more than a 30 percent increase when Pier Milwaukee reopened alone; and creating and restoring 26 boat slips, with 23 more planned in the future, yielding the potential for increased revenue from slip rentals and tourism.

Buffalo River

The Buffalo River caught on fire in 1968 and has long suffered from considerable water pollution. The Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper has worked for decades with all stakeholders to leverage $48.5 million from the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative for cleanup of the river. Considerable environmental improvement has transformed a derelict industrial waterfront into a nautical playground with over $200 million of private sector investment (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Buffalo River restoration has been a catalyst for creating waterfront public spaces in Buffalo that have generated considerable economic benefits. Photo: Joe Cascio

Concluding thoughts

The cleanup of pollution hot spots in the Great Lakes has proven difficult and has spanned many decades. Such restoration work has helped reconnect people to their waterfronts in ways that enhance community well-being. Indeed, the cleanup of such legacy pollution has become a springboard for local communities to convert areas that were once a detriment to economic growth into valuable community and economic assets for all. Economic benefits assessments have proven to be important tools to: sustain long-term momentum in urban environmental restoration work; manifest return on investment; and attract champions and advocates for sustaining funding from governments, foundations, and businesses to help finish the job of cleaning up AOCs. Other key lessons include:

- establish a compelling vision that can be carried in the hearts and minds of all stakeholders;

- recruit a well-respected champion;

- establish networks with broad support from key stakeholder groups;

- establish core delivery team, focused on outcomes and success;

- build trust and ensure cooperative learning;

- secure seed funding for projects that will attract other funding partners;

- evoke a sense of place in all projects;

- measure and celebrate successes to sustain momentum; and

- recruit and train sustainability change agents and facilitators.

John Hartig

Detroit

I agree with what this article says as far as it goes. However, there is a serious problem of phosphorous loadings into Lake Erie which is getting worse. The most cost effective way to reverse this problem is to plant vegetative buffers around streams. Less however, is being accomplished in this regards than the situation in the earlier 1990s, before the closing of public tree nurseries.