To endure in the coming century, cities like Dubai will have to lead the world in innovation for sustainability.

We step off the plane at Dubai International Airport—the third busiest in the world—and the surroundings are familiar: faux granite, glass, stainless steel, arrival/departure screens, duty-free shops, food courts, escalators, the usual. Maybe a bit grander than most, but familiar. We move through customs, hit the duty-free for a few bottles of wine (we’ll want them; it takes about a month to get your alcohol-buying license).

Then we step outside with our host, and it hits us. Slams us, really. It’s 7 pm and 45 degrees C (113 degrees F). The concrete is still releasing heat. It’s so ridiculously hot; we laugh because we’ve been told that it will be ridiculously hot. We didn’t believe it. We’ve lived in hot, dry places. We’ve been through the Mohave, Phoenix, the Great Basin. This is different. We were warned.

We’ve heard stories of people coming to live in Dubai fleeing after a few months, or even weeks, as the heat was just too much. Literally leaving all their belongings, driving to the airport, abandoning their car, and getting on a plane. Every place has its apocryphal stories.We push our luggage to our host’s SUV, load up, and notice a late model white Lexus parked next to us. It’s coated with several months of fine ochre desert powder—abandoned. Someone has finger-scrawled on the windshield a single word: “Coward!”

We’ve arrived in Dubai during the hottest month of the year, the middle of August. My wife has taken a job here. I’m along for the ride. I want to learn as much about this place as I can in a few weeks. I’ve heard a lot about Dubai: Instant city. Growing skyscrapers like weeds (I count hundreds of active construction cranes). A stunning skyline. Las Vegas of the Middle East. Winter playground. Huge per capita ecological footprint. And also, few natural resources—little energy, water or arable land. What’s going on here?

The contrasts between this desert kingdom/metropolis and my squeaky green hometown of Portland, Oregon, are stark. Hot versus cool. Dry versus wet. Car-focused versus bike-dominant. Fast paced versus laid back. Dishdasha versus flannel. A recent commitment to sustainability versus a half-century of green planning. And some similarities: an excellent food scene, five months of perfect outdoor weather, and tourists flocking to shop and play (Dubai) versus chill and play (Portland).In the next few weeks, I’ll visit the Dubai Design District, the Dubai Desert Conservation Reserve, the Emirates Wildlife Society, NYU Abu Dhabi, and the Masdar Institute for Sustainability. I’ll talk with new acquaintances, and visit a dozen malls (Dubai has 71), souks, and warehouses to help furnish our apartment and learn my way around. What follows are first impressions of a fascinating place. First impressions are important (people and cities alike strive for good ones), sometimes insightful (our eyes are often open widest in novel environments), but also incomplete (we often don’t know to look for).

I’m coming in with assumptions. Dubai and its oil-rich neighbor, Abu Dhabi are growing at breakneck speed, in one of the hottest, driest environments on earth. How will Dubai’s 2.8 million residents endure in the long run with virtually no natural water or energy resources, and six months of daily high temperatures exceeding 38 degrees C (100 F)? Dubai’s only significant food crop is dates. Despite ambitious public transportation plans, the city is designed for automobiles (as was Portland, ca. 1960), with urban development spread across the desert in patches. The combination of high temperatures and urban patches makes the city un-walkable. Contrast this scene with contemporary Portland: planned growth, ample water, fertile soils, hydropower, bike-able and walkable.

Everyone says you need a car in Dubai. It’s true. For now. Modern Dubai rose from a modest regional port of 40,000 in 1960, centered on Dubai Creek (a lagoon, not a creek), to a sprawling metropolis of 2.8 million today. Unless you live in one of the high rises near the Dubai Metro rail, which runs a mile back and parallel to the coast, you’ll be driving. Even if you live along the Metro, you’ll probably be driving. Public transportation is present, even ample, but waiting for a bus in 45-degree C heat makes an air-conditioned car an attractive option. If you live in one of the dozens of developments southeast of the main strip, you’ll definitely be driving.

Here’s the reason. Dubai’s basic transportation infrastructure—massive freeways, complex cloverleafs, self-contained subdivisions, malls clustered toward the coast—was designed for the automobile. I’m told that Dubai’s leadership is moving to re-engineer transportation systems. But roads are the skeleton of any city. This will take a while. (On the other hand, things happen quickly here: just mix concrete, steel, asphalt, and money, and voila!)

In the meantime, there’s one feature of Dubai’s road system that really stands out to a new driver: U-turns. Whoever designed the road system had an affinity for U-turns. They’re everywhere. You often have to drive a mile or more past your destination, and then U-turn back to your target. I want to know how this pattern emerged.

Here’s another wayfinding challenge: Emiratis don’t use addresses to navigate; they use landmarks. If you give your native Emirati Uber diver an address, they may get lost. But if you say, “go inland, just past the race track, and then turn right at the Spinney’s Market”—they’ll know exactly where to go.

One thing long-term residents tell me repeatedly is, “When I got here, there was nothing west of Old Dubai. We used to drive 15 miles west through the desert to hit the Hard Rock Café.” The 25 kilometers of skyscrapers along the coast that give Dubai its iconic skyline—that was desert 20 years ago.

Dubai’s unique development, wayfinding, and U-turn dependency trip me up the moment I pull away in my rental car on the west end of the city—and lead to an arresting sight. The city ends abruptly in a confusing nest of freeway cloverleaf interchanges—some still under construction—spilling me out onto the road to Abu Dhabi, and to my right, along the coast, the biggest power plant I’ve ever seen. I later learn that the DEWA Jebel Ali a 10-gigawatt natural gas plant powers most of the city and desalinates the equivalent of 200 Olympic pools of water per day. Dubai makes no small plans. Since I missed my U-turn, I’ll be driving past several exits for the largest deep-water port in the Middle East, until I can back-track.

OK so “driving Dubai” is a new experience, kind of like driving Los Angeles if all the freeways had been built since O.J. Simpson’s famous hejira. Time to try public transportation.

I leave my car at Emirates Mall in “mid-town” Dubai, which is connected to the elevated Dubai Metro train. It’s efficient and fast and offers commanding views of the linear strip of coast and high rises, suburbs in the middle distance, and finally, desert fading into the morning haze. Twenty minutes later I’m walking along Dubai Creek (lagoon), visiting the historic district, wandering through the textile souk, and stopping at the historic home of Sheikh Saeed Al Maktoum, ruler of Dubai from 1912 until his death in 1958. The home’s courtyard is quiet, modest, and offers cool shade against the morning heat. Traditional Ecological Knowledge is at work here. It feels familiar—the courtyard plan, the shade, the small exterior windows, the cooling wind towers—this Arabic architecture traveled to Spain with the Moors over a thousand years ago giving rise to the haciendas in the arid western Americas.

So this is “Old Dubai” and Deira (on the east side of the lagoon) a modest historic pearling and gold trading port. It’s easy to envision the city 50 years ago: this, and then desert. You can tell where the edge of town was from the jumbo jets just clearing buildings 4 km away. Dubai/Deira rapidly enveloped the airport, built on the edge of town in 1960. Now the edge of town is 20 km past the airport.

I’ll drive another the 40 km past that to reach the Dubai Desert Conservation Reserve. On the way, I pass an abandoned camel racing track now surrounded by suburbs, and later on, the new Dubai Camel Racing Club. It looks like any high-end luxury horse club, just different animals. I also pass a 5-km line of slow-moving trucks waiting to exit near a large escarpment. I’m puzzled. I thought the Al Hajar Mountains were further to the east. I drive on, turn off on a dirt road toward the research center, and run into an unsupervised herd of camels. They nose up to my car to see what’s up before moving on. Passing date palm plantations and other farming operations, I notice in the distance the largest shade-cloth tents I’ve ever seen: 75 meters high, maybe a hectare in area. What’s growing under those? I soon find out when I arrive at the Conservation Center: nothing.

These huge circular tents recently held hundreds of falcons, until Dubai’s head falconer convinced the emirate’s leadership, avid falconers, that Scotland would make a better mews. Peregrine and gyre falcons and their hybrids like it a bit cooler (ok, a lot cooler). The 25,500 ha Dubai Desert Conservation Reserve originated as an ecotourism site for Emirates Airlines’ Al Maha luxury resort. The initial focus was on larger charismatic wildlife, like the Arabian oryx (Al Maha), but more systemic research and conservation now includes the full biodiversity of the region. As with most arid land, much of the wildlife gathers around water. Oddly, there is abundant water here—some it only three meters below the surface, suitable only for agriculture, and non-renewable. A recent study has estimated that UAE’s groundwater may be depleted by 2030.

On my way back into the city I take a closer look at that long line of trucks. They’re all turning off near the escarpment that’s in the hazy distance, and all are climbing up a set of switchbacks on this 200-meter-high feature. Then it dawns on me. This is no escarpment; it is the approach to Dubai’s municipal landfill. As with the natural gas-fired electric/desalination plant, it’s massive. It’s the largest landfill, with the longest line of trucks I’ve ever seen (Dubai plans to shift 75 percent of its waste stream away from landfills). So now I’ve witnessed some of the core input and output sites through which Dubai’s energy and materials flow: a world-class airport, huge deepwater port, massive energy plant, a geologic-scale landfill. More opaque for a first-time visitor are the social and financial systems that drive it all.

And the products of these flows? Well, clearly the built environment—the 25-km strip of skyscrapers, the dozens of new and recent developments scattered into the desert, requiring thousands of building cranes, and connecting freeways (and U-turns). And Dubai’s attractions—71 malls, golf courses, theme parks (e.g., Ski Dubai!).

Underlying these attractions: green habitat. That is, conspicuous displays of public water opulence—artificial lakes, wetlands, fountains, vegetation. But if you look closely, drip irrigation is the standard technology, and desert-adapted species are standard—neem, acacia, native succulents, etc.

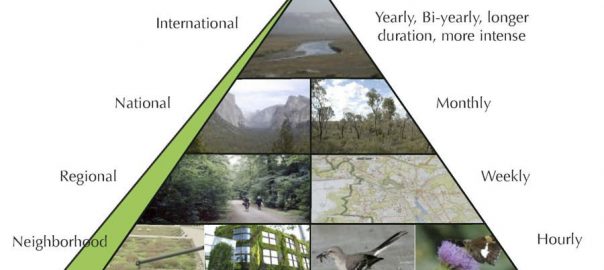

Dubai is essentially an artificial oasis. If you’re looking for wildlife, this is a good thing. The birding is excellent in Dubai’s parks, even in the hot off-season. During the fall and spring migrations, the watering and greening of the UAE desert coast vastly expand habitat for migrating birds. I’m looking forward to returning later for the fall migration.

All these visible stocks and flows of energy and materials supporting this oasis are emergent properties of perhaps a more important characteristic of Dubai: This is a trading city, a crossroads where new ideas and practices are being interwoven into a traditional culture. For the past few decades, those practices have manifested as energy, water, and infrastructure development. Now Dubai and its neighbors appear to be pouring serious money and effort into innovation for sustainability. The city’s building code for sustainability was drafted by one of Portland’s leading green architects in collaboration with Dubai’s urban planning agency.

The Dubai Design District has opened as an innovation hub, and its Institute for Design and Innovation, opening in fall 2018, will enroll 400 young designers when it is fully up and running. Further west in Abu Dhabi, the Masdar Institute for Sustainability has brought in a global faculty to design and prototype sustainable energy, water, and built-environment systems. The Masdar campus is itself a test case for high efficiency, low energy building. The exterior environment is designed to take advantage of shade and cooling winds, much like Sheikh Saeed Al Maktoum’s residence (and many others) in Old Dubai. It’s a synthesis of TEK (Traditional Ecological Knowledge) and tech.

Energy may be the easiest fix for Dubai. Solar arrays are everywhere. And massive solar farms are taking shape along the city’s outskirts. Water will be tougher. There simply isn’t any significant regional water resource. Thus, (desalinated) water availability will be energy-driven, first by natural gas, but soon enough by renewables, as gas peaks and declines. Food resources are limited as well. And even with desalinated water, massive food imports will continue. But in some ways, that’s the case for many cities. Los Angeles gets its water at great energy cost. And all cities, including wet, green Portland, have continental scale “food-sheds”. All cities are natural resource sinks by nature. Dubai, for now, is just more so.

So here’s an observation, a hypothesis, and a proposition: There are no “sustainable” cities (yet); the future of any particular city depends as much on ideas and innovation as on natural resources (unless your entire city lies at or below sea level); if this is true, global crossroads like Dubai may fare as well or better than current “greener” outposts like Portland.

Regardless of how it goes for Dubai and its UAE neighbors, the city’s ambitions may lead to potential paybacks for the rest of us. Dubai has the resources and the intention to pioneer innovative solutions for urban sustainability in arid environments. With much of the world’s population living in hot, dry climates, and with those climates getting hotter and drier, Dubai may end up being a leading sustainability adopter. The most valuable ‘product’ of Dubai may not be shopping or winter recreation or lifestyle—it may very likely be innovation for sustainability. I’m headed back to learn more.

Peter K. Schoonmaker

Portland

Leave a Reply