Any urban greenspace without a “friends group” and cadre of stewards faces an uncertain future. Guerrilla action may be necessary.

In the fall of 1970 I was sitting in a mammalogy seminar at Portland State University where I was a teaching assistant in the university’s biology department when Al Miller, a gangly, be-spectacled volunteer with the local Audubon chapter walked into the room hoping rope some naïve young biologists in the running battle between the city parks department and local conservationists to protect a neighborhood wetland.

Soon thereafter I found myself sitting in stuffy, cramped Audubon library hammering out letters to the city on an old Underwood manual typewriter, the sort where keys stick together every few strokes. That I had never set foot in Oaks Bottom was irrelevant. Our recruiter’s passionate pitch, combined with the fact that he had worked for the state fish and wildlife agency and was an Audubon emissary, was good enough for me. Trust among co-conspirators is an essential ingredient for success.

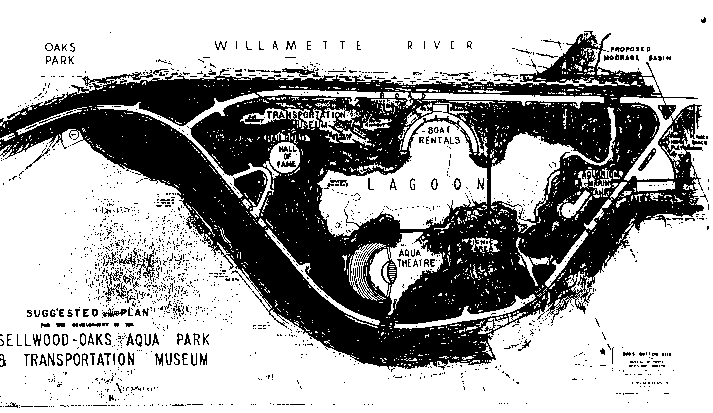

Twelve years as Audubon’s Urban Naturalist my first assignment was a resurrection of the campaign to save Oaks Bottom. The challenge by then was more about benign neglect than by earlier plans to fill the wetland for a motocross course, children’s museum, and “walk of heroes.” City parks were still resistant to designating the wetlands as a wildlife refuge, something for which the local neighborhood association, Audubon, Sierra Club, The Nature Conservancy, and local outdoor writer had long lobbied.

It’s a Sign!

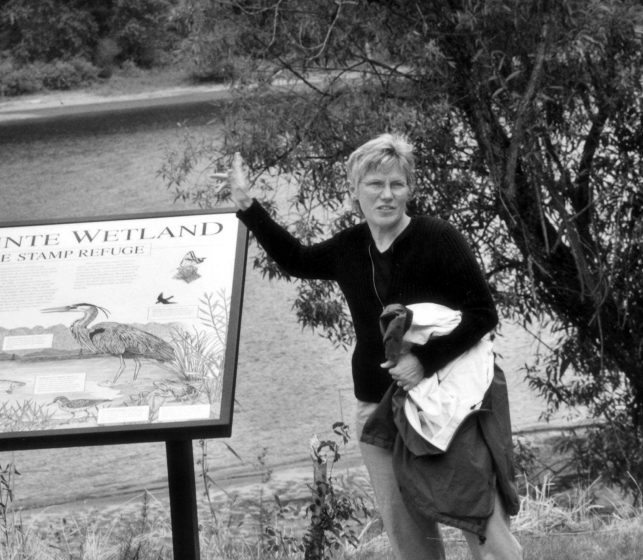

Such sustained recalcitrance demanded new, more direct action tactics. If the city would not act, we would. A sympathetic state fish and wildlife biologist was an early ally in what would be a prolonged campaign to secure the wetland’s permanent protection. Joe, the biologist, supplied us with official “wildlife refuge” signs. They were intensely bright, highly visible yellow plastic signs that would be visible from great distances. To avoid implicating the biologist, I sheared off the reference to the agency, created a stencil and spray painted “City Park”, creating a passably official looking sign that read, Wildlife Refuge, City Park.

With forty brilliantly lettered signs in tow my side-kick Jimbo Beckmann (image 6) and I toted a twelve-foot ladder, hammer, nails and, armed with a bottle of Jim Beam bourbon proceeded to nail up the signs around the wetland perimeter, thereby establishing, by fiat, that we unilaterally declared the city’s first urban wildlife refuge. Amazingly, in a short two weeks our local newspaper, The Oregonian, ran an unrelated story that a deceased person that had been found in…Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge. Not the publicity we sought, but the first-ever public recognition of the wetland’s new, guerrilla-ordained status was fine with us. From that point onward the media routinely referred to the wetland, which formerly it had derisively labeled a “bottomland swamp”, as Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge. Progress.

Rewriting history

If you want to change public policy, sometimes hearing it from officialdom is the surest, quickest route. Later that same year a city official was to give a speech commemorating the dedication of Audubon’s new Wildlife Care Center. Having worked with city staff I for some time I was on friendly enough terms that I was shown the prepared text. I asked if it would be possible to alter the text…just a tad….to insert an insignificant reference to “Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge.” The staffer, seeing no harm in making such a small change, agreed. Later that morning came the first formal reference to the wetland’s refuge status from a prominent elected official. Progress.

Bottom Watchers!

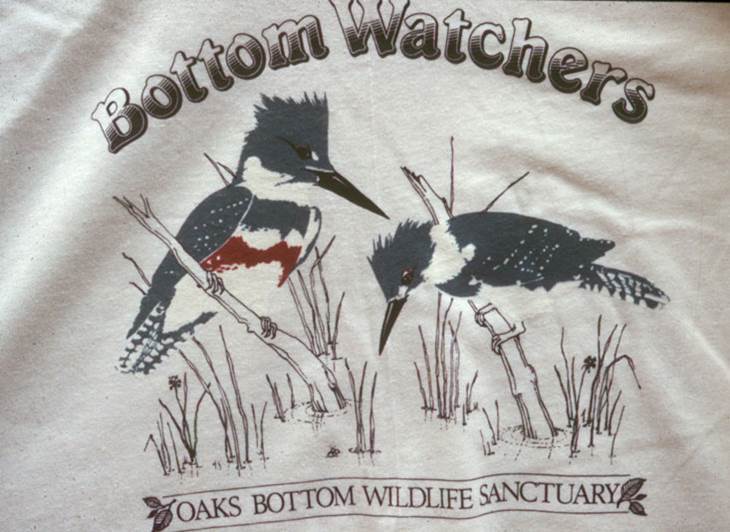

Any urban greenspace without a “friends group” and cadre of stewards faces an uncertain future. What can be done today can be undone tomorrow, through neglect or development pressure. We needed to create a movement of grassroots activists. I went to Martha Gannett, a graphic artist and Audubon volunteer, who created colorful Bottom Watchers t-shirts (image 8) with two colorful kingfishers keeping watch over the bottoms. Voila, we launched the Bottom Watchers and Friends of Oaks Bottom. With an organized group of volunteers, we reached out to the park’s volunteer coordinator and started annual clean-ups and trail maintenance crews. The Youth Conservation Corps had created an unpaved, two-mile loop trail in the early 1970s which was soon overrun with a prickly, impenetrable wall of Himalayan blackberry. The bottoms has also become a favored location for pickups to lose tons of household garbage, construction debris, and decaying animal carcasses. An annual garbage haul was instituted and signage…official this time…helped staunch the flow of garbage into the bottoms.

Getting formal

By the late 1980s, the time had come to (mainly) drop the guerrilla tactics and get more formal status from city bureaucrats. Formalization came by way of writing a wetland management plan. Working with Portland Parks and Recreation’s natural resource staff and the local Soil and Water Conservation District two other advocates, one an EPA wetland ecologist the other a local high school science teacher and I drafted an Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge Management Plan, which was promptly adopted by City Council. This came eighteen years after Al Miller’s recruiting gambit and going on thirty years earlier game, but ultimately unsuccessful, efforts. It’s no wonder I adopted another conservations motto of endless pressure, endlessly applied as my own. That mantra speaks to one of the most frequent paths to success…dogged determination.

Once the Master Plan was adopted, we were on the road to permanent protection of the wetland as the city’s first official urban wildlife refuge. However, we quickly learned a plan without funding is a hollow victory. Next came intense battles over the bureau’s natural area budget, which was perennially underfunded even though eighty-five percent of the city’s 10,000-acre portfolio were habitat parks. Once we secured additional park funding and engaged another bureau with a more robust ecological staff, the city initiated ongoing restoration efforts to manage the bottoms with an emphasis on ecological function. Public access was controlled by retention of an unpaved perimeter path while a new “rails with trails” regional path provided unfettered access on the wetland’s western edge.

Over the past twenty years, professional ecologists with Portland Parks and the city’s Bureau of Environmental Services have removed blackberry, English ivy, and other invasive species and replanted with native species. Formal interpretive signs have replaced the now disintegrated signs Jimbo and I posted over three decades ago. A massive habitat restoration plan is in the works which will re-connect the bottoms’ floodplain with the adjacent Willamette River to enhance salmonid habitat.

Art and nature

My most recent, and probably last major effort to focus public attention on the importance of Oaks Bottom to the city’s commitment to protecting urban biodiversity and providing nature nearby was the creation of what I believe is the largest hand-painted wall mural on a building in the country. This effort grew from a 1986 project with our then mayor, Bud Clark and local muralist Mark Bennett of ArtFX. Bud and I worked to declare the Great Blue Heron Portland’s official city bird, and Mark created a huge heron mural on a building overlooking Oaks Bottom. Twenty years later Mark called me and asked when we were going to finish off the entire building, the Portland Memorial Mausoleum.

The result is 55,000 square foot mosaic depicting birds and other wetland denizens. The mural is visible from across the Willamette River, more than a mile distant. Just another way to celebrate nature in the city and draw the attention of thousands of cyclists, walker, and joggers who use the regional greenway trail at the wetland’s western edge.

While Oaks Bottom is a singular story capturing the need to engage in a “by any means necessary” approach to urban conservation, there are myriad other stories, locally, nationally and internationally, all spearheaded by creative urban greenspace advocates each providing inspiring tales of preserving nature in the city, thereby contributing to the nature of cities. The Nature of Cities is dedicated to telling those stories.

Mike Houck

Portland

On The Nature of Cities

Mike Houck is Executive Director of the Urban Greenspaces Institute and continues in his role of Urban Naturalist at the Audubon Society of Portland and serves on the board of The Nature of Cities.

Leave a Reply