For better or worse, 2017 was a historic year for both Mexico and Mexico City. This can be summed up in two numbers: 100 and 32. The first number celebrates the one hundredth anniversary of Mexico’s Constitution, approved on 5 February 1917, and renowned as the first Constitution in the world to incorporate social rights. The second number, 32, marks the remembrance of the deadly earthquake that killed more than 30,000 people and devastated Mexico City on 19 September 1985. Two very different anniversaries, of course. One, but distant and hardly provoking any popular emotion; the other one random and unforeseen, but still very present in the memories of at least three generations.

Mexico is a country fiercely proud of its history and traditions. Mexico City’s current Mayor (or, more precisely, its Jefe de Gobierno—Head of Government), Miguel Ángel Mancera, enacted and officially presented the first local Constitution on the same day the country commemorated the first century of the national one (although, legally, it goes into effect on 15 September 2018). Later in the year, by a tragic coincidence that challenged all probability statistics, exactly on the same day and just a few hours after the annual “mega-simulacro” (city-wide earthquake drill) had ended, another tragic tremor shook several central and southern states, leaving more than three hundred victims and thousands of buildings affected.

At first glance, it is certainly not evident how these two very different events are related one to another. Yet another anniversary might provide a clue for making a connection, because 2017 also memorializes two decades of the first-ever elected mayor in Mexico City, a milestone that opened the pathway for a significant transformation of the political life in the city and the country. Both the popular imagination and the academic analysis coincide in placing the spontaneous, massive, and outstanding social mobilization that followed the 1985 disaster as one of the key ingredients in the push towards a more democratic state with stronger civic participation.

Progressive movements, the Right to the City, and a new Constitution

Since then, progressive initiatives from social movements and civil society organizations have become the norm in this megacity, and policy changes are being implemented covering a broad range of issues, from housing and neighbourhood betterment programs, relevant improvements in urban mobility and sustainability, childcare and economic support for single mothers, students, and the elderly, to sexual and reproductive rights, Indigenous peoples’ and LGBTQ rights, to mention just a few.

The Mexico Charter for the Right to the City (2010) is certainly a crucial part of that legacy, as it is now the Mexico City Constitution (2017), the first one in the world to incorporate the right to the city at the local level. It is understood as a collective right that implies the “full and equitable use and usufruct of the city, based on principles of social justice, democracy, participation, equality, sustainability, as well as the respect for cultural diversity and the respect for nature and the environment”. The right to the city should guarantee “the full exercise of human rights, the social function of the city and its democratic management, assuring territorial justice, social inclusion and equitable distribution of public goods with citizen participation” (Art. 12).

Besides this definition, the groundbreaking Constitution took several other principles and elements from the Mexico City Charter, a document drafted inside a collective process that included local grassroots organizations, NGOs, activists, academics, and professionals, as well as international civil society networks and the local government—and that also had international repercussion in relevant documents, such as the Global-Charter Agenda for Human Rights in the City (2011) and the New Urban Agenda (2016), both of which explicitly recognized the right to the city.

Promoted as a Charter of Rights, the new Mexico City Constitution includes a long and detailed catalogue of internationally and nationally recognized human rights (civil, political, social, economic, and cultural rights), as well as more “original” ones. Among them, it is worth mentioning:

- the right to public space, as collectiveand participatory commons that serve political, social, educational, cultural, and recreational functions (Art. 13.D);

- the right to mobility, regarding access to an integrated multimodal and sustainable public transportation system, the protection of pedestrians and the prioritization of the non-motorized options (Art. 13.E);

- the right to free time, as a fundamental element for well-being, allowing inhabitants to enjoy rest, leisure, social, and recreational activities, as well as look after their personal care (Art. 13.F).

Most probably taking inspiration from the National Constitutions of Ecuador (2008) and Bolivia (2009), the Mexico City Constitution also incorporates the notion of nature as a collective entity with its own rights—and instructs the subsequent elaboration of an ad hoc regulatory law (Art. 13.A). The recognition of the right to a healthy environment and the right to the natural and cultural heritage for the present and future generations, as well as the rights of Indigenous people and campesinos, are all included in the text, while the capital of the country is recognized as a multilingual, multiethnic, multicultural, and welcoming dynamic territory.

The new Constitution also creates several new and complex institutions for the city, including an Integral Human Rights System and a Democratic and Prospective Planning System (that should be linked to each other and incorporate substantive citizen’s participation), a local Congress, an Economic, Social and Environmental Council and the possibility to determine ‘Municipalities’ (Alcaldías) within its territory.

To get the text ready on time, the process of elaboration was relatively short and, at least for some, a bit rushed. The federal political reform—a necessary step to allow the elaboration of the Mexico City Constitution—was approved by the Senate at the very end of 2015, after intense debate considering the details of the capital city’s new legal status, its attributions and the related institutional arrangements at federal, local and—somehow—metropolitan level.

In February 2016, the Mexico City Mayor appointed a Drafting Committee and an external Advisory Group, both integrated by a wide range of local leaders and experts on human rights, culture, urbanism, and environmental fields. By September 2016, the Constitutional Assembly was installed, and the Mayor officially delivered his draft to the deputies to work on, with the last day of January 2017 as their deadline. Finally, the first-ever Mexico City Constitution was formally enacted on 5 February 2017, marking the one hundredth anniversary of the National Constitution.

Who should pay? Who should benefit? Social contract and urban planning

As expected for any discussion of a new social contract, the process had to first overcome some challenges and heated debates on sensitive topics. Many of them were finally included, such as the medicinal use of cannabis, the option of assisted suicide for the terminally ill, living wills, abortion, recalling of elected officials (revocación de mandato), or the strengthening of direct and participatory democracy mechanisms.

But some relevant rights were left out. One of those, several observers noted, was the issue of land-value capture (known generically as captación de plusvalías in Spanish), considered by many experts and activists as a fundamental instrument for the advance of urban reform and the right to the city principles. An initial formulation was included as part of the Article 21 of Mexico City’s Draft Constitution, stating that “the increments on the land value as a result of the urbanization process will be considered part of the public wealth of the city. The law will regulate its use for restoring the ecosystems and the degraded areas of the city”.

This was not an original proposition. Similar instruments, under various names, are being used in several countries around the world and even in other Mexican provinces/states. Technically known as a density bonus, or up-zoning in return for community benefits formulas (known in Spanish as transferencia de potencialidad, contribución por mejora, derecho de edificación, etc.), these types of planning tools have been implemented for decades in Brazil, Canada, Colombia, the USA, France, the UK and in cities in many other countries.

While I’m not an urbanist or an academic in this field—nor a lawyer, by the way—in my simple words the explanation is as follows: in exchange for the authorization of new real estate projects, private investors and constructors must make monetary or in-kind contributions to the city for financing infrastructure, social housing, and other crucial needs for some specific neighbourhoods (ideally the most disadvantaged ones) or the city/metropolitan area as a whole.

It took some weeks—until the beginning of December 2016—but the proposal provoked an intense and charged public debate. In just a few days, all major national media (including print, radio, and TV) covered the issue with several dozen news articles and interviews. As a result, by the end of the month, all mention of the topic was totally removed from the proposal, and no reference to it was made in the final Constitution. Additionally, any reference to the term that was already part of the new local Housing Law, approved on those same days, was immediately removed to avoid further debate and controversy.

Does it sound like a coincidence? Of course it wasn’t. But what ignited the fire in the first place? And why did it take only a few days to impact the draft of the Constitution in such a definitive way?

The answers to these questions are, as contradictory as it sounds, both alarming and hopeful. Three elements make the case for it: 1) sincere concern from ordinary citizens regarding unclear and potentially unjust norms that are believed will affect ones personal interests and assets; 2) deliberate manipulation from some major mass media outlets searching for polarizing subjects, ideological indoctrination (presented, of course, as “common sense” and “in the general interest”) and easy popularity gains (with the business/economic benefits related to it, of course); and last but not least, 3) political calculation from the opposition sector to discredit and attack the current administration of Mexico City.

Regarding reflections and lessons learned, an in-depth, detailed review is of value.

Social mobilizations and public debates on sensitive topics

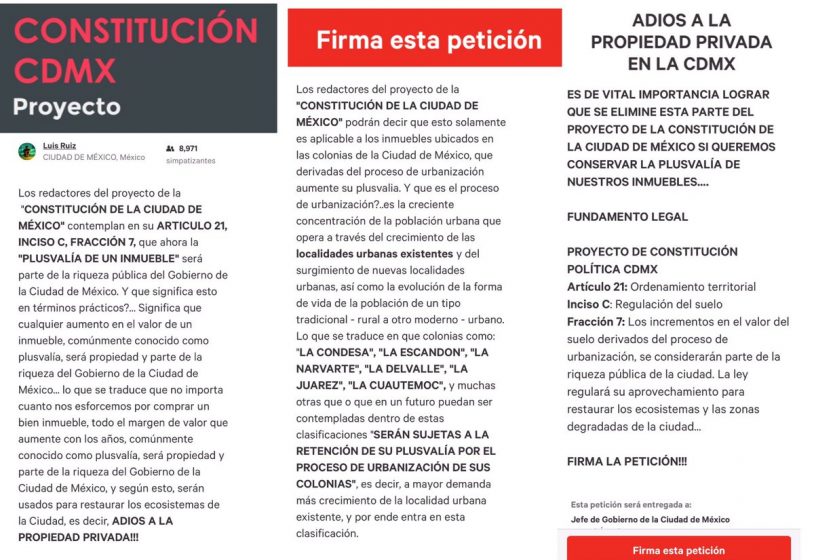

The first element of note was an online petition, initiated by a citizen indignant with the possibility of having the potential increases in the price of his property taken away by the government, as an additional and “anti-constitutional”, “hidden” property tax. Using a clearly provocative title (“Goodbye to Private Property in Mexico City”) and hashtag (#NoSeRobenMiPlusvalía, something that roughly translates into English as “Don’tStealMyLand-ValueIncrease”) the petition, started on 5 December and directly addressing the Mayor and other authorities involved in the constitutional process, sparkled intense mobilization on social media and achieved tens of thousands of signatures in less than forty eight hours. On its last update (13 December), the author claimed as a collective achievement the removal of all references to land-value capture both in the local Constitution and the local Housing Law (for more details see https://www.change.org/p/manceramiguelmx-elimina-el-articulo-165-166-y-167-del-codigo-fiscal-de-la-ciudad-de-m%C3%A9xico-para-las-personas-f%C3%ADsicas-y-el-ciudadano-com%C3%BAn).

As expected, national and local media quickly picked up the wave and, with a snowball effect, soon generated public controversy. Within the four days of publication of the petition, most major national newspapers, TV channels, and radio stations had covered the debate and arranged interviews with some of the key actors involved. Although at least sixty media pieces were produced, only a few of them offered deep and balanced analysis of the complex issues at stake (for a full compilation see here). Rather, many were deliberately partial and sensationalistic, presenting a fairly common urban development compensatory mechanism targeting corporate investors as an expropriation and confiscatory measure that would affect homeowners. Some among them went as far as launching editorials referring to “Mexico-Sovietitlán”, perversely playing with the historic Mexico-Tenochtitlán name (lugar de los Mexicas donde abundan las tunas—the place of the Mexicas were the fruit of the nopal abounds—as the Aztecs named this place more than seven hundred years ago), while at the same time openly criticizing “the Mexican Left” for being “still attached to old ideas about income redistribution that have proven their inefficiency in many countries of the world” (which certainly generated strong reactions, including an extensive one by Deliberated Democracy).

Clearly dazzled by the immediate popularity of the petition and the media attention it captured, the conservative party saw an opportunity to gain some traction and rapidly requested the removal of any proposals referring to the land-value capture from both the Constitution and the Housing Law. To the amazement of many, the rest of the political opposition immediately followed them, forcing the constituents into a reversal on this topic with almost no time for debate or to elaborate on the arguments. The Mayor and other actors emphatically denounced the situation as another move to try to harm the current city government.

Of course, many questions arose. Among those, was this occurrence merely a coincidence or an orchestrated campaign? It is hard to know. But this is not the first time controversy surrounds this topic, even if the prior examples come from well in the past. More than forty years ago, when state’s representatives were discussing the Vancouver Declaration and Action Plan as part of the first UN Conference on Human Settlements (known as Habitat I), a Canadian organization claimed that the proposed land management instruments represented “a one hundred percent confiscation of benefits”. And more or less those same terms were seen in the debates in Brazil and Colombia, some years after that. In all those cases, the contents were maintained in the proposed political and legal instruments.

In any case, there are some lessons to be learned from these examples. The confusion over terms, found valid by the majority of the voices in the Mexican case, should be taken as a wakeup call for many of us: community leaders, activists, professionals, academics, public officials, and decision-makers. How do we properly address this linguistic dimension, when the social change we are promoting is strongly linked with terms and concepts that might be totally new to the general public? And how do we react when the meaning is being intentionally manipulated to generate confusion and opposition? At the same time, how can we overcome the hyper-specialized niches in which we are trained and we develop our practice and the specific terminology associated with them, that usually makes wider dialogues—and any associated action—very difficult? What kind of urban pedagogy will be necessary to build a renewed and reloaded civic culture to collectively face current urban challenges and alternatives?

Earthquakes that shake society and politics

Almost exactly one year after the inauguration of the Mexico City Constitutional Assembly, a tragic coincidence shook everybody and everything. On 19 September 2017, just hours after the mega-simulacro, a 7.1 earthquake frightened millions of Mexicans in the central area of the country. With the epicentre only 120 km away from Mexico City, the seismic activity was of such intensity in the capital that, within seconds, several buildings were collapsing; minutes later, the situation was chaotic.

Once again, the immediate social mobilization, with young people as clear protagonists, was remarkable. The emotive and inspiring images traveled the world, with thousands of citizens trying to help as they could, and finding even the tune to sing together “Ay, ay, ay, ay, canta y no llores” (Ay, ay, ay, ay, sing and don’t cry, as part of the chorus of Cielito Lindo, the famous Mexican song) during the initial terrible hours of improvised rescue efforts.

As has become the norm, social media and the internet played a fundamental role in the self-organization of aid rapidly producing and distributing very precise maps and lists of places affected; locations of shelters and gathering centres, immediate reports outlining the specific needs at different sites, names of the missing and of volunteers ready to offer support. Bikers played a particularly crucial role, as public transportation systems and several major roads were collapsed for nearly a week after the quake.

Once again, the society was shaken, and the political regime too. Both the national and the local government were accused of being too slow and inefficient in an emergency situation, and then of actually obstructing the more effective and transparent efforts from civil society. But the repercussions of the crisis were even more relevant. The popularity of the federal authorities has since fallen probably to its lowest mark, and the Mayor of Mexico City had to postpone his resignation to be able to run as a presidential candidate in the next national election (scheduled for July 1st, 2018).

Hundreds of organizations, including several Habitat International Coalition members and allies, are involved in the reconstruction of the capital and other Mexican states. Many among them have signed important joint declarations urging the local and national government to take the appropriate measures to guarantee that dignity and human rights are respected, and the affected communities are adequately engaged. A particular call was made to avoid evictions and displacements, as well as to take into account the traditional materials and construction knowledge of the population while facilitating the social production of housing and habitat. At the same time, the public opinion urgently demanded an investigation into the legal status of the affected buildings, their compliance with the regulations and the administrative and judicial actions linked to these issues.

One year on

In this context, at the first anniversary of Mexico City’s Constitution, it is not clear how its implementation will advance. On the one hand, the legal text is a corollary of social change and political innovation of the past two decades; on the other, it represents the collective ambitions that should guide institutional actions over many decades to come. The public controversies around some of its more relevant content revealed that people are alert, ready to claim their rights and demand accountability from their representatives. At the same time, the earthquake reminded us that, as in many other places around the world, society is not sitting around waiting for the government to act.

Struggles for spatial justice, human rights, and democracy are certainly interconnected and have a long history in Mexico’s Capital City. As the previous official slogan claimed, this is a “City in Movement”. So let’s get inspired and keep going.

Lorena Zárate

Mexico City

Add a Comment

Join our conversation