Cities, like nature, consist of complex organisms that evolve. For most of natural and human history change occurred slowly enough for inhabitants to adapt without impacting the overall health and functionality of the underlying natural systems. However, with the advent of industrial-scale technology turning fossil fuels into climate-heating greenhouse gases, organisms shaped and altered by human activity have gone through such rapid transformations that to simply adapt to the changes in our environment can no longer guarantee sustained well-being for most inhabitants.

With the gap between human demand on nature and nature’s capacity to meet that demand at an all-time deficit, the effects of this imbalance are manifesting all around; from the rapid melting of polar sea ice, to the dramatic loss of coral reefs, to severe wildfire seasons such as the one that devastated California last fall. It is thus incumbent upon us, the human species, who have damaged the organisms upon which all life depends through nonrenewable energy-enabled inefficient design of our living spaces and wasteful patterns of overconsumption, to restore the life-sustaining balance of the planet’s ecological budget.

To operate on a large enough scale to reverse the unsustainable infrastructure patterns that make all of its users into unwilling ecological debtors, the most natural place to focus is the largest, most complex and populated artifacts humans have created: cities. We must do this in a way that not only reacts to a deteriorating environment but also turns our cities into engines of restoration for the bioregions within which they reside. This transformation from an extractive to a regenerative entity can only take place with the input and buy-in from as broad a coalition of stakeholders as possible. In other words, for systems to change, as many inhabitants as possible have to get in the habit of collaboratively pulling in a new direction.

This participatory approach to planning is the premise of Peer-to-Peer Urbanism, a practice that provides citizens access to accurate open-source information and knowledge about their built environments, engaging them in decision-making processes as well as in the design and implementation of local solutions. For the past five years, the model has been piloted in cities around the world through Ecocity Builders’ Urbinsight project, bringing together community leaders, local government, academia, open data, and citizens to re-envision their urban spaces.

Using participatory action research methods, GIS mapping, and urban metabolism tools, the pilots have empowered participating low- to middle-income communities to be involved in their own neighborhoods’ transformation. From the research and data collection stages all the way to implementing on-the-ground changes, the peer-to-peer process has enabled participants from Cairo to Lima and Medellín to analyze and map the material flows that are most relevant to their quality of life as well as the overall health of their local urban ecosystems.

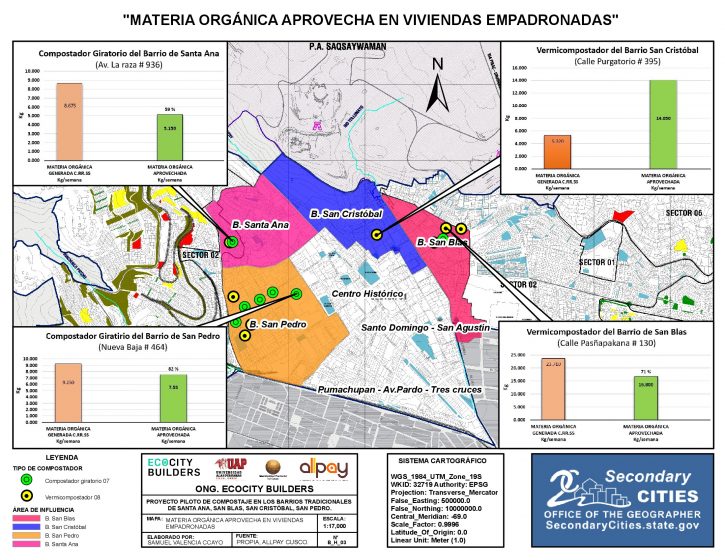

In Cusco, Peru, for example, the collaboration between Team Urbinsight and project participants has yielded new insights into and solutions for the city’s waste and consumption patterns. Implemented under the umbrella of the U.S. State Department Office of the Geographer and Global Issues’ Secondary Cities initiative, the participatory research process between residents of the city’s historic neighborhoods, local university students, and city planners provided the city with unprecedented citizen-sourced layers of data, and ultimately resulted in a composting program built for and by the communities.

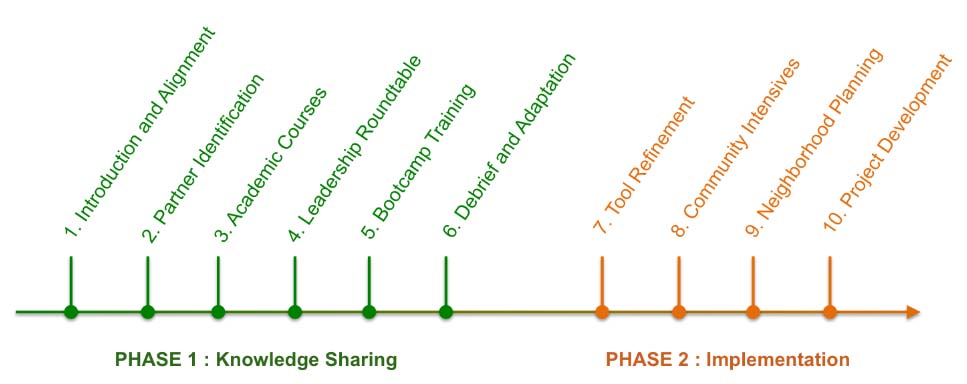

While the peer-to-peer approach does, and in fact, is designed to vary from city to city depending on each place’s unique physical and sociocultural conditions, Cusco serves as a great window into how the process can play out successfully and in tangible terms; from the knowledge sharing phase all the way to implementation, as laid out in Urbinsight’s educational compendium, the EcoCompass.

Allow me to provide an illustrated look at the chronological stages of community engagement and holistic planning that has taken place in the historical capital of Peru.

Knowledge sharing phase

Through Ecocity Builders’ previous Latin American project partnerships, developed during conferences and other collaborations, Cusco was identified as a pilot city with a diverse range of academic, government and community stakeholders interested in exploring a peer-to-peer process of urban planning. During an initial scoping tour, academic lead, Santos Mera pointed out that a big challenge the City of Cusco faces in dealing with its garbage crisis is that existing government statistics are often superficial, unclear, and outdated, with quantitative information hard to come by. This makes the proposition of obtaining neighborhood-level data, how much garbage is produced, what materials are used, and where things come from, hugely appealing.

After examining available city data and existing conditions on the ground, the partners determined that the four neighborhoods of San Pedro, San Cristóbal, San Blas, and Santa Ana in the city’s historic center are best suited for inclusion in the initial phase of the project, as they could serve as neighborhood archetypes to be replicated elsewhere at a later stage.

Through scoping sessions and word of mouth, the team was connected with neighbors and community groups to discuss citizen concerns and priorities. Partnerships were formed with community organizers like San Pedro’s Gricelda Pumayali Vengoa and Indira Reyes, who also heads Ingenio Verde, a local organization already involved in greening neighborhoods, and an important liaison with community members eager to participate in the project.

During initial resident and student-led tours of the neighborhoods to map out existing conditions and assess needs, the piles of overfilled plastic bags in streets too narrow for trash collectors to maneuver emerged as a top concern and a consensus built around using the project’s urban metabolism analysis tools to map out material flows and consumption patterns.

A series of professional workshops were held at Universidad alas Peruanas where the team introduced participating faculty, students, local officials, and planners to the ins and outs of creating a dynamic geospatial mapping platform that visualizes multiple data types, along with the tools and methods of the peer-to-peer approach to data collection. Learning the core concepts of GIS and UMIS (Urban Metabolism Information Systems) with guided tutorials, participants set up a case study of their city and neighborhoods based on UN Sustainable Development Goal 11—urban policy.

The next step in the process was to bring together the students—trained in conducting environmental audits—with residents of the neighborhoods selected for study, as part of the leadership roundtable. Since a consensus to focus on waste had been reached during previous meetings, the partners decided that the roundtable should also serve as a boot camp; in addition to discussing the community’s specific concerns and priorities, the student teams also conducted quality-of-life surveys and collected consumption and waste data from residents.

Forty-one residents attended the event and completed the surveys documenting their consumption patterns and identifying their knowledge of the materials that pass through their homes. The students came away with new ideas for trash removal and reduction, including adjustments to collection schedules and routes, centrally located collection points, and special public education programs. However, everyone agreed that the most immediate, impactful, and easy-to-implement strategy for reducing the city’s garbage volume and improving citizen’s quality of life would be a low-cost, custom-designed residential composting program.

Implementation phase

To kick off the project’s next phase, over 50 community leaders, city staff, academics, students, and citizen activists gathered for an event facilitated by Urbinsight Project Director Sydney Moss to discuss the program’s methodology and Phase II goals, timeline, and partnerships. Santos Mera recapped how the research conducted during Phase I had led to the compost pilot, and his student team was poised to start gauging interest in the composting program among community members, and to begin the education process for home owners. Luz Palomino Cori, Deputy Director of the Environmental Engineering Department of Universidad Alas Peruanas, explained how these new partnerships strengthen planning decisions for the city in the years ahead.

Fourteen of the community participants volunteered to be part of a household audit to determine the exact composition of the material flows through their homes and businesses. This participation would yield the type of detailed data needed for deeper material analysis. With the help of the students, the residents went through their solid waste, weighing and sorting materials by type—organics, plastics and glass, and paper and cardboard. The data collected showed that 90 percent of San Pedro’s waste could be recycled, with the organic—and thus compostable—rate at 50 percent.

While the need for residential composting has been on the radar throughout the project, these findings generate excitement among community members, not only about reducing waste but about creating nutrient-rich soil to use in their gardens. This is where the peer-to-peer process connects the importance of valuable data and knowledge with the broader goal of realigning human conduct in balance with nature. “Our ancestors, the Incas, used the composting method a lot, but unfortunately it was forgotten”, says Virginia Mendigure Sarmiento, one of the participants from San Pedro. “So to reclaim that knowledge and take care of nature again is very gratifying and inspiring”.

To obtain more information on spaces that could support compost models, the team conducted a second survey, including questions about the characteristics of housing construction, housing area types, and the number of inhabitants per dwelling. Coordinated with the leaders of each neighborhood, Ecocity Design Advisor Stephanie Weyer, and Ingenio Verde Director Indira Reyes and her youth go from home to home to gauge the level of commitment within the four communities. They explain to those interested what they would need to do to participate in the project and receive feedback on their preferences in modeling styles, what tools they own, and any ideas or concerns they have.

“These students did so much work”, says Weyer. “We walked around, went to all these different stores, negotiating with different people all the time to make this happen. And the communities allowed us into their homes. They let us borrow their tools”!

Based on the information gathered during the surveys, the community leaders and students gathered to design models for the composting units. They decided on two low cost, easy to build options for residents to choose from—a rotary model or vermicomposting bin. After collecting and buying the materials, joined by the residents and future composters, they assembled ten vermicompost and seven rotator units during the first round of construction.

But the work was far from done. With the units up and running, the students and members of Ingenio Verde stopped by participating households once or twice a week, checking on pH value, temperature, humidity, and size of organic matter, comparing decomposition rates for each model and saving the data for further research. They also attended various public events and street fairs to demonstrate the models and spread the word about the project throughout other communities in Cusco.

Within a week of installing the 17 composting models built in the pilot phase, community members reduced organic waste by 95 kilograms (about 200lbs). The team is proud that this 95 kg of materials will not end up in the streets or waterways, but will instead help nourish plants and gardens, and even has the potential to earn people money. They calculate that if the municipality continues to raise awareness of the composting opportunities and the project is replicated and scaled up among the 15,000 residents of Cusco’s historic neighborhoods, over 60,000 kg of organic waste each week could produce positive impacts for the community and the environment, instead of ending up in the dump or the stomachs of rats, flies, and dogs that transmit diseases.

Being able to make such projections through working with the neighborhood level material flow data generated by the household audits and environmental surveys is just one of the benefits of the peer-to-peer process. As Santos Mera points out, a less measurable yet perhaps more valuable asset of the participatory method is the synergy generated between different urban demographic groups that might pass each other by in more conventional approaches to urban planning. “Here we have citizens who know about local problems, needs, and information gaps, collaborating with academics who can help with the research and create a proposal, which is reviewed, refined and approved by city managers who have been connected to the communities and the research from the get-go”.

As for those city managers like Abel Gallegos, getting such detailed, bottom-up, crowdsourced neighborhood data is quite a treat. It enables the city to make informed decisions on where to direct its resources as well as build its capacity to integrate broader underlying parameters like ecosystems or climate change into city management.

“A fundamental outcome of the surveys was to focus our interventions on the separation of materials because that allows us to determine where to reduce, where to reuse, and where to recycle”, says Gallegos. “And knowing that 50 percent of our total stream is organic makes composting into the highest impact intervention to optimize the city’s solid waste management”.

Ultimately, for a large-scale transformation of resource management to take place, engaged citizens will need all the support they can get from their local government. As far as San Pedro composter and activist Virginia Mendigure Sarmiento is concerned, one of the key objectives of the project is to work with the provincial municipality to ultimately insert it into an ongoing process of participatory planning. “With the proof of concept we now have, the only thing we need is the political will to raise environmental awareness among aspiring civil servants and for that awareness to turn into policy at the town hall level”, Sarmiento says.

She is convinced that this kind of focus on education is the most cost-effective way to deal with Cusco’s mounting garbage problem in the long term.

“In order to scale up composting and recycling in the communities, authorities have to do more than just tell people to stop throwing away and start sorting their trash. They have to help them understand that these practices also improve the conditions of our planet”.

Sven Eberlein

Oakland

Add a Comment

Join our conversation