about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

The “smart city” is still more of an aspiration than a reality, but many cities have initiated programs and projects. The projects themselves tend to lean toward technological outcomes such as energy efficiency, traffic and pedestrian flows, and so on. The public, to the extent that it is aware of the smart city at all, probably imagines the same.

But if our goal is for better cities—cities that are better for both people and nature—what can smart cities do for us? How can the technology of smart cities be specifically directed toward the creation of ecologically sophisticated cities that serve human well-being? Can the benefits they provide be distributed justly and equitably, for everyone and not just a few? Can the services they provide be about more than just technology?

But if our goal is for better cities—cities that are better for both people and nature—what can smart cities do for us? How can the technology of smart cities be specifically directed toward the creation of ecologically sophisticated cities that serve human well-being? Can the benefits they provide be distributed justly and equitably, for everyone and not just a few? Can the services they provide be about more than just technology?

How might we create cities that are not only smart, but wise?

We asked out panel: Smart cities are coming. It is important that they be as much about nature, health, and well-being as traffic flows, crime detection, and evermore efficient provision of utilities. How will this be done?

about the writer

Eric Sanderson

Eric Sanderson is Vice President for Urban Conservation at the New York Botanical Garden, and the author of Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City. His upcoming book, Before New York: An Atlas and Gazetteer, will be released in 2026.

Eric Sanderson

What we truly need to improve the nature of cities are smart and wise people and institutions, who consciously and deliberately use data and information to create natural cities.

Like many Americans of a certain generation, I spent a portion of my misspent youth hunched around a table playing Dungeons & Dragons. One of the things I liked best about D&D is that at the beginning of each game, we would roll three dice to give our characters a set of defining attributes: strength, intelligence, wisdom, constitution, dexterity, and charisma. I thought it was brilliant that the designers of the game recognized the difference between intelligence and wisdom, which is sorely lacking in most of the 21st century world, and in particular, in the discussions around smart cities. Intelligence, smartness, information is the capacity to know facts about our cities. Wisdom, motivation, justness, is the capacity to act positively and bravely on that information to make the city better. We have many examples of intelligent people who do unwise things; we may know some of those rare people who are wise without being unusually intelligent, but what we truly need to improve the nature of cities are smart and wise people and institutions, who consciously and deliberately use data and information to create natural cities.

A natural city by definition fits seamlessly into its environment, much as forests, grasslands, and waters do; it gives as much as it takes; and it lasts for a long time.

In New York City, my colleagues and I have been trying to generate the smart, wise, natural city that we believe is essential to the future. One part of that is having a shared set of goals for the nature of the city, as Bram Gunther and I wrote about previously here. Nature in our view (and the view of over 40 other institutions) should be seen as fundamental to the functioning of the city as public safety, or education, or health. In New York we have police and fire departments to keep us safe, and departments of education and health to help us be smart and healthy, but the management of nature is scattered across agencies (NYC Parks Department, NYC Department of Environmental Protection, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, National Park Service, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, etc.), with no clear lines of responsibility that link back to a shared set of goals for the city as an integral and wise whole.

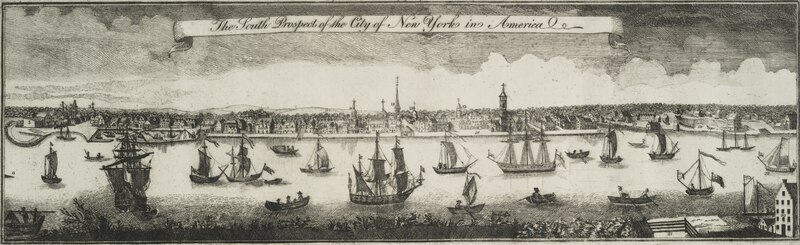

We have also been working hard to give New Yorkers tools to generate and share ideas about the city of the future. As I wrote about here, Visionmaker.nyc is a free online tool for ecological democracy. Anyone with an internet connection can zoom to a neighborhood of interest, see the ecosystems of that part of the city now as well as the historical, pre-development landscape, then reimagine the neighborhood they would like to see in the future. Those scenarios of a future can take into account climate change and/or play around with lifestyles through integrated toolsets. Each change generates a call to a set of models that give comparative and quantitative metrics about the water cycle, carbon flows, biodiversity patterns, and population density, where the user’s vision is evaluated next to that present-day neighborhood and the area as a natural landscape.

Finally, as this brief gloss on Visionmaker suggests, we have found it incredibly useful to contrast New York today with its pre-development, “wild” state, via the Mannahatta and Welikia Projects. Historical ecology provides unique perspectives that speak to wisdom even more than intelligence. Urban historical ecology reminds us that our cities have not always had their current form, despite their monumentality. The past gives us insights into the way nature shapes the land and waters where our cities are built. If the sea level rose 120 meters, as it has in New York City over the last 20,000 years, should we be shocked that it may rise another meter over the next century? Most importantly though, historical ecology inspires. Nature is beautiful and fascinating and robust in ways that speak volumes to our overcrowded and over-busy time. Sometimes one can glimpse that beauty today, in the rustle of leaves in a city park or in the motion of salt marsh grasses as the tides come in, but to realize the former vastness of this landscape and the productivity of its indigenous ecosystems is to open our hearts to the potential of the future and sting us with visions of what has been lost.

about the writer

Seema Mundoli

Seema Mundoli is an Assistant Professor at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru. Her recent co-authored books (with Harini Nagendra) include, “Cities and Canopies: Trees in Indian Cities” (Penguin India, 2019), “Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India’s Cities” (Penguin India, 2023) and the illustrated children’s book “So Many Leaves” (Pratham Books, 2020).

about the writer

Harini Nagendra

Harini Nagendra is a Professor of Sustainability at Azim Premji University, Bangalore, India. She uses social and ecological approaches to examine the factors shaping the sustainability of forests and cities in the south Asian context. Her books include “Cities and Canopies: Trees of Indian Cities” and “Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India’s Cities” (Penguin India, 2023) (with Seema Mundoli), and “The Bangalore Detectives Club” historical mystery series set in 1920s colonial India.

Seema Mundoli and Harini Nagendra

Transforming into smart cities that are aesthetically pleasing to a few, while ignoring the role of nature in cities for survival of the many urban poor is a further setback to the development of equitable cities.

Spring is in the air—for us, urban residents in the Global South, these are said to be times of plenty. Cities in India, for example, are believed to be the engines propelling economic development and employment generation. There is hardly any product that cannot be bought or service that cannot be accessed in the Indian urban market. If there is a scarcity, it seems to be of thought: thought in planning and vision for our cities. India recently launched an ambitious Smart City Mission that envisages the development of 100 smart cities across the country. Information and communication technology, and high-quality infrastructure are the pillars on which smart cities are to be developed. However, the role of nature in the smart city project to improve the quality of life of urban residents is severely limited in conception. The role of urban nature is envisioned only for the development of open spaces for recreational purposes—and a brief mention of addressing urban heat effects. This, at a time when India is reeling under a host of environmental problems.

As has now become a regular occurrence, New Delhi (India’s capital city), was blanketed with smog in the winter of 2017. Air pollution levels reached hazardous levels that warranted the closure of schools for several days. The “solutions” included short term technical fixes such as deploying water cannons to combat pollution. At the same time, a sizeable chunk of funds was allocated under the smart city project to—yes, you guessed it—to build multi-level automated parking! This beggars belief, since private vehicles contribute considerably to the pollution in the city. The smart city proposal for New Delhi makes no mention of efforts to disincentivize private transport, or increase green cover that can help mitigate air pollution, and urban heat islands.

Nature in cities of the Global South has a very important role to play in supporting livelihood and subsistence needs of urban residents, especially the impoverished. However, the budgetary focus of smart cities on ecological spaces—be it lakes, riverfronts or urban greenery—seems to be on landscaping to promote recreational use. Inequity in urban India is already high, and natural spaces in cities are essential for the resilience of urban marginalised groups who depend on a range of raw materials such as food, fuelwood, fodder, and water that they access for free. While an amount of Rs 70,000 million (approximately 1.1 billion USD) is allocated for riverfront projects and open spaces in 58 cities, there is no mention of incorporating the local needs of communities who have traditionally accessed these spaces. Transforming into smart cities that are aesthetically pleasing to a few, while ignoring the role of nature in cities for survival of the many urban poor is a further setback to the development of equitable cities.

Then there is the wave of recent urban disasters—disasters that could have been averted if we paid attention to the ecological base on which cities are built. Urban floods damaged several cities across India, because of haphazard construction that destroyed the original hydrological landscape of the city. Yet smart city projects are planned without identifying and incorporating environmental risks of disaster. Chennai experienced unprecedented rainfall in December 2015. The situation was exacerbated by large-scale construction on wetlands, and the disruption of a well-working natural drainage system, the resultant flooding caused tremendous loss of life and property. However, the smart city budget for Chennai allocates an inadequate sum of Rs 200 million (approx. 315,000 USD) for disaster management to combat flood and tsunamis.

Clearly, the vision for smart cities is in stark contrast to the reality of urban living. The very basic needs of residents met by nature that contribute to their quality of life: such as clean air for all, natural resources on which many survive, and a safe environment against disasters, are ignored, while technology and infrastructure quick-fixes are being promoted. The House of Stark’s motto “winter is coming” in the fantasy book series Game of Thrones are words of caution about difficult times that lay ahead. We would well be warned about the implications of pushing for data and tech fixes for smart cities while ignoring the less glamorous, every day, irreplaceable role of nature in contributing to the health and well-being of urban residents.

about the writer

Shaleen Singhal

Dr. Shaleen Singhal is a Professor at TERI School of Advanced Studies with 21 years of research and academic experience working on sustainable urban development issues in India and UK. He is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy, UK and a Visiting Fulbright Fellow for Yale University, US.

Shaleen Singhal

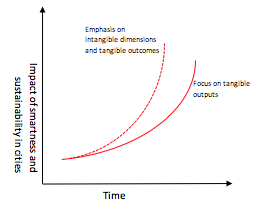

Intangibles for tangible outcomes

Smart city efforts will be futile if the current challenges of inequality, poverty, and unsustainable consumption are not addressed.

A new and enhanced comprehension of smart cities is elemental particularly in the context of cities in emerging economies that display a greater degree of complexities and barriers. Effectiveness needs to take over efficiency! Traditional indicators on outputs relating to investment and infrastructure creation require a shift towards outcomes relating to the quality of life of the city’s inhabitants including the vulnerable population of urban poor. While smartness may ascertain a city’s capacity to mobilize advance technologies including information and communication technology (ICT) in establishing sentient cities with futuristic infrastructure, it should also influence change in a city’s reach and delivery of quality services. To benefit current and future billions that are and will be living in emergent cities, leapfrogging and breakthrough in thinking, strategy, action, and evaluation are needed that must go beyond change as usual. An effective way to realise this is by engaging with young minds and to create a new cadre of professionals with systemic thinking and with an appreciation of the sustainability dimension of urban development. Institutions with a conventional outlook have demonstrated a limited capacity to adapt towards the need for upfront integration of sustainability into all tracks of city development. Globally, this is an apt time for such integration particularly by resurgent cities that are in the process of redevelopment. It is critical for cities to create synergies among smart city strategies, redevelopment strategies, and strategies for resilience to comprehensively enhance competitiveness with enduring sustainability.

For cities in emerging economies such as Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa (BRICS), and others, smart city led technological advancements need to fortify redevelopment strategies such as retrofitting of ageing building stock and upgradation of infrastructure for resource efficiency and low carbon development. Such advancements shall also promote a shift from greenfield to brownfield investments while dealing with inherent socioeconomic and environmental challenges of inner cities. Any smart city aligned progressions can be truly effective if they also augment a city’s resilience with the ability to absorb, recover and prepare for future economic, environmental and physical, social and institutional shocks.

It is evident that agile cities such as from the BRICS region are growing in terms of population and gross domestic product (GDP), emerging as important destinations for investments, adopting innovations relating to technology, research and development, and becoming economically competitive. However, these cities also witness numerous challenges such as rising income inequality, growing slum populations, unsustainable consumption patterns, increasing pollution levels, and resource scarcity. Any changes towards being a smart city will be futile without measurable contributions in addressing such challenges and positively influencing the human development index (HDI) alongside economic competitiveness. Real opportunity should not be lost or limited to just intensifying the debate on what and how smart cities should be! Moreover, it should also not just be an unwritten strategy to bail out or prop up the real estate sector! It is imperative that the smart city transformation process adopts a shift in focus from tangible assets, actions and rankings towards important intangible dimensions that are critical to enhancing living standards. Positive changes in dimensions such as but not limited to—culture and heritage sensitive urban management, scalable exemplars of rich governance, and innovative financing mechanisms such as through leveraging a city’s assets, are critical. Others dimensions, such as efficient green infrastructure and unbuilt environment, behavioral change for sustainable consumption and production practices, strategies for inclusiveness, sustainable redevelopment and resilience, connectivity, imageability, and happiness quotient of inhabitants are a few expected outcomes from smartening a city movement.

As we advance on a pathway of upgrading our select cities to smart ones, examples of a few inevitable questions are—how far has the city progressed on HDIs? Has social capital of the city increased? Has the city achieved significant improvement in access and quality of services such as education, health, security, and key environmental services? How self-reliant has the rural catchment become? Is the city footprint decreasing while increasing productivity? How in command are the local institutions to further propel the city’s smartness? How happy are citizens from the outcomes? Are outcomes further harnessing cultural uniqueness of the city, its people, assets and resources? This is evidently, a case for rephrasing smart cities as “smart sustainable cities”! This pathway should raise the significance and impact of intangible dimensions as complementary to tangible outputs for smart and sustainable cities in emerging economies.

about the writer

Huda Shaka

Huda’s experience and training combine urban planning, sustainable development and public health. She is a chartered town planner (MRTPI) and a chartered environmentalist (CEnv) with over 15 years’ experience focused on visionary master plans and city plans across the Arabian Gulf. She is passionate about influencing Arab cities towards sustainable development.

Huda Shaka

The first step in creating a smart city is to set holistic, measurable objectives that address the needs and aspirations of its residents.

While smart cities may be coming, many of the concepts, technologies, and partnerships that will make them happen are already here today. Some see commercial and property development opportunities in this new world, others see data and privacy risks. A third group is emerging who are advocating for utilizing smart technology to offer entire communities (not just paying clients) healthier, better-connected environments and wider economic opportunities. Ultimately, smart cities focused on nature, health and well-being will also need traffic flow, crime, and utilities data. The difference lies in the ownership, access to, and usage of the data to serve a higher purpose.

As an example, traffic flow data can be used to achieve both smoother vehicular traffic and safer planned pedestrian crossing conditions (location and signal timing) for improved health. As long as the wider community does not have access to this data or an understanding of how it is used, there is a risk that it will be used to maximize benefit for private interests.

To address this issue, a number of factors must be considered. The first step is to set holistic, measurable objectives for a city which address the needs and aspirations of its residents. Next is determining the type of data needed to manage and assess a city’s performance against the objectives. It is often at this step that government departments and officials stumble, as they focus on measuring and reporting what is easily measurable as opposed to what is important to be measured. For example, a public transport department may measure the total distance covered by bus trips, as opposed to the percentage of residents served by buses or the number of car trips avoided. Clearly the latter two indicators are more complex; however, they provide a much better basis for decision making as they link more directly to quality of life from a social and environmental perspective. It is likely that complex indicators may require more creative ways of measurement, including qualitative user satisfaction surveys, cooperation across government entities, participation by the private sector, and engagement with the community. This is all achievable in our age of smart cities.

Finally, there is the process of sharing this information and analysis with all city residents and users, in an accessible way—both from a technology and language perspective, amongst other factors. This a good test of the type of data being collected. Are the data telling community members what they want to know about their built and natural environment? Does it empowering them to make more informed decisions? Or are the data mostly being used to demonstrate that a government is “smart” or that a particular technology is a good investment?

The digital justice principles (access, participation, common ownership, healthy communities) provide insights into what a world of people and nature focused smart cities could look like. It is a city where data are collected and shared for the benefit of all. This is partly about what data are collected but mostly about who has access to the data and technology, and what benefit they bring to communities.

about the writer

Bernhard Scharf

Born in Salzburg, I found my way to the University of Natural Resources & Life Sciences Vienna to study landscape planning and architecture. My master thesis already dealt with ecological and economical solutions for turf areas, so called flowering turf. 2006 I started my scientific work at the Institute of Soil Bioengineering and Landscape Construction. The focus from then on was the development of technical solutions to allow the broad application of green infrastructure in the context of urban challenges. In 2014 I co-founded the Green4cities company to close the gap between research and planning praxis. Today I am senior scientist at BOKU and CTO of the G4C company. More details here.

Bernhard Scharf

The smart city community needs intensive exchange and mutual learning to find the best solutions to integrate human needs in urban planning, comprehensively and efficiently.

What is a smart city? Is it a buzzword? Sometimes this impression is created, especially when you look at various real estate projects that are advertised as “smart” because of an info screen at the entrance hall, etc. while being absolutely conventional otherwise.

Is there a clear definition what a smart city is? In the field of research “smart cities” are understood as highly diverse. Most smart city research projects focus on a set of topics relevant to the scientists involved, such as the internet of things, social sciences or new mobility concepts, green infrastructure, etc. Apart from the thematic diversity, there is a common interface to all projects: they address the needs of people today and in the future. What we can observe is a significant change of perspective in how we plan and develop our cities: a human-centered planning approach going beyond the scope of traditional planning. No longer do people have to adapt to the city. It’s the other way around. The city has to deliver what people need.

That means that urban planning and design changes dramatically. Many people, especially investors but also experts, are afraid of the change towards smart cities. They try to keep their routine and patterns. While change is perhaps the only constant there is.

So how can we proceed on this path and create smart cities? I think we have to change attitudes, traditions, patterns, and routines. But most of all the following two aspects:

More resources and time for planning processes

The planning of new urban districts or retrofitting built city areas is highly complex. Thanks to modern technologies such as building information modeling (BIM), etc. the planning is extremely efficient and allows planners to address many aspects in a short time; and almost the same time (and money) for planning as many decades ago, when things were not as complex. Developers and municipalities expect that the planning experts comply with the given time frame and regulatory framework. As a result, we see planning experts struggle to balance the scope of services, time and money, trying to achieve the best results with the available resources.

The role of planning processes, especially concerning smart cities, needs to be much more appreciated. We need to be aware of the fact, that the cities we build today will remain—thanks to high European technical standards—for many, many decades, very likely until 2100 or beyond. At that time different climatic framework conditions, urban density and age-composition of the society will be a given. A smart city needs to account for all of these changes, today. Therefore, the planning process needs to be interdisciplinary including civic participation, allowing for work on interfaces and synergies with fewer budget and time restraints. Planners have to point out their importance in such complex planning processes to define the quality of projects and security of the investment for a very long time. Researchers estimate that, regarding an average planning project, the planners budget accounts for only 3 percent of the total lifetime cost of buildings, while defining the 97 percent of lifetime cost significantly!

Understanding the city as nature

More than 70 percent of Europeans live in a city today. Every weekend people tend to “visit” a piece of nature, a park, a forest, a mountain. Why? There is no regulation or obligation to do so. As proven in many health studies nature experience helps to recreate and relax, improving health, concentration and so forth. Obviously, citizens’ lack of nature experience in their direct vicinities, the urban fabric, leaves them with great desire and demand for nature.

In the history of city development nature has been perceived as a source of danger, out of control and order. As a consequence, cities somehow banned nature or kept it “clean” and under control in pots or parks. “We need to stop war against nature”, claimed Gary Grant at the European Union Green Infrastructure Conference 2017 in Budapest. Ecosystem services reduce urban heat island effects, flash flooding, air pollutants, noise, and increase the attractiveness of the urban fabric, creating healthy and appropriate habitat conditions for people. Nature has to be understood as an essential part of forward-looking and smart cities, as partner and ally to overcome many aspects of urban deficiencies.

Smart cities are coming. There is no doubt about that. There are some remarkable projects realized in Europe, but the process is ongoing and still experimental in a way. The smart city community needs intensive exchange and mutual learning to find the best solutions to integrate human needs in urban planning comprehensively and efficiently.

about the writer

Gary Grant

Gary Grant is a Chartered Environmentalist, Fellow of the Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management, Fellow of the Leeds Sustainability Institute, and Thesis Supervisor at the Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment, University College London. He is Director of the Green Infrastructure Consultancy (http://greeninfrastructureconsultancy.com/).

Gary Grant

An adequate tranche of smart city investment should be spent on monitoring the environment, so that designers, planners, and managers can invest money to save money, restore nature, and make our cities more resilient to climate change.

Our knowledge of cities is limited. Millions of us take in the sights, but we don’t necessarily understand what we see and how it works. We take the built environment for granted and rarely take the time to analyse it or make plans to improve it. Help is needed from all-seeing and quick-thinking sensors and computer networks. We don’t have a full picture of the biodiversity that occurs in cities. There are maps which show the location and extent of habitats and various green spaces. Trees, especially street trees, are usually catalogued (take for example Singapore’s heritage trees). Knowledge of wild vegetation in cities is incomplete. Urban naturalists record birds in most cities, with specialists looking at particular species, like the swift for example, but investigations of invertebrates are uncommon. The first task for the smart city is to use cameras and sensors, working with artificial intelligence, to complete the mapping and cataloguing of natural features within our cities. This will include soils, watercourses and waterbodies, habitats (both on the ground and on buildings), as well as species. Sound, for example, is being used to identify and map wildlife. An interesting example of this is the monitoring of bat activity in real time in London’s Olympic Park. The description and cataloguing of urban nature need to be completed, so that we can see where it is missing, where it can be enhanced, and where management should be focussed, to restore nature for its own sake and for the well-being of citizens. Smart city technology can be harnessed for this purpose. It will make monitoring more affordable and more effective.

Nature affects and is affected by its physical setting. Surprisingly little is known about the various and changing microclimates in our cities. The phenomenon now known as the Urban Heat Island Effect (UHIE) was first described more than 200 years ago, however, ask city planners about how much of a problem the UHIE is in a particular precinct, chances are they will not know. The permeability of surface cover, evapotranspiration rates, and surface temperatures are inter-related, and these parameters can be measured using infra-red photography. An excess of sealed surfaces can lead to problems with surface water flooding and combined sewer overflows which pollute watercourses. Cameras and digital thermal sensors can be networked in order to monitor the whole city, looking for hot spots, where green infrastructure can be created to fix these problems.

Air quality and water quality are monitored, usually to the minimum standard required by legislation in any jurisdiction. New York City, for example, monitors air quality at 150 stations. Water quality tends to be measured in selected watercourses at particular times in the year or in response to incidents. It is well established that vegetation intercepts and absorbs air pollution, and that soil cleans water, however little is known about how particular combinations of soil and vegetation in urban settings provide these ecosystem services. As the costs of sensors that measure pollutants fall, it should be possible to monitor entire urban areas, to understand where the most serious problems are occurring and how natural features are affected and are reducing the impacts of pollution on citizens. More detailed and wider scale monitoring will reveal more about how polluted cities are but will also help city planners to prioritise expenditure and target interventions and continuing management.

We are told that there will be significant investments in smart city initiatives. 1.2 trillion dollars by 2022 according to one estimate. Without a concerted effort from those of us interested in nature, it is possible that almost all of this investment will be centred on measuring the flows of energy within wires and water within pipes, on smoothing traffic flows, detecting crime, and servicing businesses and government. This is all well and good for the most part. However, an adequate tranche of that investment should be spent on monitoring the environment, so that designers, planners, and managers can invest money to save money, restore nature and make our cities more resilient to climate change. We need to be shielded by more water, soil, and vegetation and this must be added in a smart way, which will require smart city techniques and technologies.

about the writer

Helga Fassbinder

Helga Fassbinder is an urban planner, political scientist, writer, professor emeritus of the University of Technology Eindhoven, The Netherlands, and University of Technology Hamburg, Germany. She lives in Amsterdam and Vienna. Fifteen years ago, she developed the concept of ‘Biotope City – the City as Nature’, and started the Foundation Biotope City, which is exploring new urban aesthetics and ethics. The Foundation has produced the BIOTOPE CITY JOURNAL since 2006. Meanwhile the first ‘Biotope City’ is being built in Vienna. www.biotope-city.net

Helga Fassbinder

To read this post in German see here.

A needed smart city filter: Do smart city measures contribute to a more socially fair good life, without externalising associated costs, spatially and socially?

Smart city as a social-ecological challenge

The term “smart city” is used by actors of the cities—political decision-makers, planners, administrations, companies, housing associations, etc.—in the mood for very different programs and objectives. One gets the impression that “smart” is a label which is often used only to “sell” any upcoming investment/measure, as it calls up the image of technological innovation and progress even if, in reality, the technological innovation is only marginal or its effects are questionable.

First of all, it’s about giving the concept of the smart city a definition.

We may agree that we live in times of global ecological crises, going further: in times of socio-ecological crises. By this I mean that we live in times of a multi-faceted crisis, which in many countries cause or at least intensify a social crisis by reaching or even exceeding the limits of ecological resilience. Thus, one can speak of a global social-ecological crisis. Migration flows and wars give expression to this.

That means as a consequence: if the renewal and transformation of our cities into smart cities is to have a forward-looking positive impact, then they must contribute to solving or at least mitigating these multiple socio-ecological crises rather than to exacerbate global negative ecological and social effects.

To further clarify the definition of “smart city” let’s add the following attributes: sustainable, resource efficient, ecological, nature friendly, and socially acceptable.

But what do these attributes imply in the concrete? This raises the question: How far are we going with sustainability and resource-saving, etc.?

I propose to add, as a sort of “filter” for “smart city” measures in the above sense, by asking the following questions:

- Do these measures contribute to a more socially fair good life, without externalising associated costs, spatially and socially?

- Are the smart city measures contributing to a global social-ecological transformation?

Our current Western-style life is largely based on the spatial and social externalisation of the costs of its production: costs of production in so-called low-wage countries, exploitation of natural resources in such countries, export of our waste to such countries etc. This means that our good life is based on the misery of humans and the extermination of nature (mineral resources, biodiversity, water, nature’s ability to regenerate in general, etc.) in these countries.

For this fact the German political scientists Ulrich Brand and Markus Wissen have coined the term “imperial mood of living”. A few months ago, they published a book on this subject, subtitled “The Exploitation of Man and Nature in Global Capitalism” (1) The publication has received great attention and recognition and has come on the bestseller list of the magazine “Der Spiegel”.

This great response is pleasing because it shows that many people are aware that their lifestyle is leading to overexploitation of nature and people in a global dimension. Reflecting this, they may also be aware that this “imperial mood of living” in the long run will destroy the very basis of their own well-being: it accelerates climate change worldwide, it is destroying the basis of life of more and more people in these countries and depletes natural resources (e.g., rare earths) at a speed that makes their replacement by technological innovations very questionable.

What does that mean for the concept of the smart city? What does that mean for us, who are involved as experts in the planning and implementation of so-called “smart” measures?

First of all, any measure planned under the “smart city” label should be reviewed not only for its impact on climate and nature at the regional and national level, but it should also be checked as rigorously as possible with regard to the possible global externalisation of effects and costs.

Just a few examples:

This criteria brings into question many small measures currently being touted as “smart”. For instance when small human activities, easily carried out by hand, (e.g., to switch on a light) are unnecessarily are replaced by electronic triggers, and thus now require the consumption of, among other things, rare earths.

Even the conversion of individual vehicles to electric cars, a change now propagated in many countries, and touted as sustainable, comes into question. The decision to convert to electric cars results not only the premature replacement of fossil fuel-powered cars (and thus a destruction of value), justified with gains in energy efficiency and reduced carbon emissions, but it also neglects to account for the resource consumption and carbon emissions made by the production of these new electric cars. It also does not take into account the consumption of raw materials for electric batteries, materials which perhaps do not even exist in sufficient quantities for the scale needed. What is the balance sheet?

In addition, the switch to electric vehicles also requires a new, large-scale infrastructure of charging stations, also associated with an increased consumption of resources, and rare earths.

I do not argue against electric cars in general. But for improving the flow of individual traffic, the more sustainable alternative, instead of subsidising each new electric car, is certainly to give priority to the development of the public transport network, and, for urban traffic and transport, to promote and support the use of human-powered forms of transport, such as bicycles, with safe bicycle lanes and safe parking.

On the opposite side, there are other “smart” measures which certainly do not or hardly have any negative externalised effects. This includes, for example, the comprehensive greening of buildings, urban farming, and urban gardening. These measures contribute to the strengthening of native biodiversity, they reduce summer temperatures, delay the outflow of water during prolonged heavy rain, and can support small-scale corporate structures in gardening and agriculture, with no or minimal externalisation of effects and costs.

Conclusion:

The critical review of any as “smart” planned measure concerning their global spatial and social impacts, could lead, in the end, to a checklist of the social and ecological gains and deficits of “smart measures”. Such a checklist could help planners, critical public, and decision-makers to decide whether or not to carry out what one has in mind and, with regard to minimizing the effects of externalisation of costs, could help us look for better or best alternatives.

Such a checklist would contribute to an efficient social-ecological transformation that could modify and reduce the “imperial mood of life” by transforming our cities.

Notes:

Brand, Ulrich/Wissen, Markus (2017): The Imperial Mode of Living. In: Spash, Clive (ed.): Routledge Handbook of Ecological Economics: Nature and Society. London: Routledge, 152-161.

Brand, Ulrich/Wissen, Markus (2017): Social-Ecological Transformation. In: Noel Castree, Michael Goodchild, Weidong Liu, Audrey Kobayashi, Richard Marston, Douglas Richardson

Görg, Christoph/Brand, Ulrich (lead authors)/Haberl, Helmut/Hummel, Diana/Jahn, Thomas/Liehr, Stefan (2017): Challenges for Social-Ecological Transformations: Contributions from Social and Political Ecology. In: Sustainability 9(7), 1045; doi:10.3390/su9071045

SMART CITY ALS SOZIAL-ÖKONOMISCHE HERAUSFORDERUNG

Die Bezeichnung ‘smart city’ wird von den Akteuren der Städte – politischen Entscheidungsträgern, Verwaltung, Unternehmen, Wohnungsbaugesellschaften e.a. – für höchst unterschiedliche Programme und Zielsetzungen gebraucht. Man gewinnt den Eindruck, dass es sich um ein Label handelt, mit dem vielfach lediglich jeweils anstehende Investitionen/Massnahmen ‘verkauft’ werden sollen, da es das Bild der technologischen Neuerung auch dann aufruft, wenn die technologische Neuerung nur marginal oder selbst in ihren Effekten fragwürdig ist.

Es geht also erst einmal darum, dem Begriff der smart city eine Definition zu geben.

Wir sind uns vielleicht darüber einig, dass wir in Zeiten globaler ökologischer Krisen leben, noch weiter gehend: in Zeiten sozial-ökologischer Krisen. Damit ist gemeint, wir leben in Zeiten einer multiblen Krise, die durch das Erreichen der Grenzen der ökologischen Belastbarkeit in vielen Ländern eine soziale Krise hervorruft oder zumindest verstärkt. Somit kann man von einer globalen sozial-ökologischen Krise sprechen. Migrationgsströme und Kriege geben davon Ausdruck.

Wenn also der Umbau und die Erneuerung unserer Städte zu ‘smart cities’ einen in die Zukunft weisenden positiven Sinn haben soll, dann müssten sie beitragen zur Lösung oder zumindest zur Milderung dieser vielfältigen sozial-ökologischen Krisen, anstatt sie in ihren globalen Effekten noch weiter zu verschärfen.

Fügen wir also zur näheren Bestimmung der Definition von ‘smart city’ die folgenden Attribute hinzu: nachhaltig, ressourcenschonend, ökologisch, Natur schonend, sozial verträglich. Aber was implizieren diese Attribute dann im Konkreten? Hier erhebt sich die Frage: Wie weit geht die Reichweite von ‘nachhaltig’, ressourcenschonend etc. ?

Ich schlage vor, gewissermassen als eine Art von ‘Filter’ für ‘smart-city’-Massnahmen im obigen Sinne die folgende Frage hinzuzufügen:

Tragen diese Massnahmen bei zu einem sozial gerechteren guten Leben, ohne damit verbundene Kosten räumlich und sozial zu externalisieren?

Tragen die Massnahmen bei zu einer globalen sozial-ökologischen Transformation?

Unser heutiges, von westlichen Standards geprägtes Leben ist in hohem Masse basiert auf der räumlichen und sozialen Externalisierung von Kosten seiner Herstellung: Kosten der Produktion in sog. Billiglohn-Ländern, Ausbeutung der natürlichen Ressourcen in solchen Ländern, Export unserer Abfälle in solche Länder. Das heisst: unser gutes Leben ist auf dem Elend von Menschen und der Vernichtung von Natur (Bodenschätze, Biodiversität, Regenerationsfähigkeit der Natur) in diesen Ländern begründet.

Die deutschen Ökonomen Ulrich Brand und Markus Wissen haben dafür den Begriff der ‘imperialen Lebensweise’ geprägt. Sie haben vor einigen Monaten ein Buch zu diesem Thema publiziert, das den Untertitel trägt ‘Zur Ausbeutung von Mensch und Natur im globalen Kapitalismus’. Die Publikation hat grosse Aufmerksamkeit und Anerkennung gefunden und ist auf die Bestseller-Liste des Magazins ‘der SPIEGEL’ gekommen.

Diese grosse Resonanz ist erfreulich, denn sie zeigt, dass doch vielen Menschen bewusst ist, dass mit ihrer Lebensweise Raubbau getrieben wird an Natur und Menschen in einer globalen Dimension. Es wird ihnen in der Reflexion dessen vielleicht auch bewusst, dass diese ihre ‘imperiale Lebensweise’ à la longue auch die Basis ihres eigenen Wohllebens zerstören wird: Sie beschleunigt den Klimawandel weltweit, sie entreisst immer mehr Menschen in diesem Ländern ihre Existenzgrundlage und erschöpft natürliche Ressourcen (zB seltene Erden) in einem Tempo, dass deren Ersatz durch technologische Neuerungen sehr fraglich ist.

Was heisst das nun für das Konzept der ‘Smart City’? Was heisst das für uns, die wir als Fachleute eingebunden sind in Planung und Durchführung von sog. ‘smarten’ Massnahmen?

Als erstes: Jede Massnahme, die unter dem Label ‘smart city’ geplant wird, sollte nicht nur unter der Frage ihrer Auswirkung auf das Klima und den regionalen und nationalen Naturhaushalt überprüft werden, sondern ebenso streng im Hinblick auf mögliche globale Externalisierung von Effekten und Kosten überprüft werden.

Nur einige Beispiele:

Damit werden bereits viele kleine Massnahmen fragwürdig, die als ‘smart’ angepriesen werden, z.B. überall dort, wo unnötigerweise kleine menschliche Handgriffe durch elektronische Steuerung (und damit dem Verbrauch von u.a. seltenen Erden) ersetzt werden. Auch der nun in vielen Ländern propagierte Umstieg des Individual-Verkehrs auf Elektroautos, der als nachhaltig angepriesen wird, wäre noch zu hinterfragen: Er zieht nicht nur den vorzeitigen Ersatz von fossil angetriebenen Autos (und damit eine Wertezerstörung nach sich), wobei dem energetischen und CO2-Gewinn der Ressourcenverbrauch und CO2-Ausstoss bei der Produktion der neuen Elektroautos gegenüber steht, ganz abgesehen von den für Elektrobatterien notwendigen Rohstoffen, die es in diesem Ausmass wohl garnicht in ausreichend gibt. Was ist die Bilanz? Zudem: Es bedarf auch einer grossflächigen neuen Infrastruktur mit Ladestellen, auch dieses ist mit einem gesteigerten Verbrauch von Ressourcen, u.a. den seltenen Erden, verbunden.

Die nachhaltigere Alternative, um den Verkehrsflow zu verbessern, ist wohl, dem Ausbau des Netzes von öffentlichem Verkehr Vorrang zu geben, und für den Nahverkehr den Gebrauch von Verkehrsmitteln mit ‘Menschenantrieb’, sprich Fahrrädern, mit sicheren Fahrradwegen und Unterstellplätzen zu unterstützen.

Andere ‘smarte’ Massnahmen hingegen haben deutlich keine oder kaum negative externalisierte Effekte. Dazu gehört die umfassende Begrünung von Gebäuden und Urban Farming. Sie tragen zur Stärkung der einheimischen Biodiversität bei, senken sommerliche Temperaturen, verzögern den Abfluss von Wasser bei langdauernden Starkregen und können kleinteilige Unternehmensstrukturen in Gärtnerei und Landwirtschaft unterstützen, mit keiner oder nur minimaler Externalisierung von Effekten und Kosten.

Fazit:

Die kritische Prüfung jeder als ‘smart’ geplanten Massnahme hinsichtlich ihrer globalen räumlichen und sozialen Effekte könnte zu einer Liste führen, anhand der PlanerInnen, eine kritische Öffentlichkeit und EntscheidungsträgerInnen entscheiden können, ob diese Massnahme zu verantworten ist.

Eine solche Liste wäre ein Beitrag zu einer effizienten sozial-ökologischen Transformation, die im Umbau unserer Städte den imperialen Charakter unserer Lebensweise modifizieren und verringern könnte.

Fussnoten:

Brand, Ulrich/Wissen, Markus (2017): The Imperial Mode of Living. In: Spash, Clive (ed.): Routledge Handbook of Ecological Economics: Nature and Society. London: Routledge, 152-161.

Brand, Ulrich/Wissen, Markus (2017): Social-Ecological Transformation. In: Noel Castree, Michael Goodchild, Weidong Liu, Audrey Kobayashi, Richard Marston, Douglas Richardson

Görg, Christoph/Brand, Ulrich (lead authors)/Haberl, Helmut/Hummel, Diana/Jahn, Thomas/Liehr, Stefan (2017): Challenges for Social-Ecological Transformations: Contributions from Social and Political Ecology. In: Sustainability 9(7), 1045; doi:10.3390/su9071045

about the writer

Vishal Narain

Vishal Narain is Professor, Public Policy and Governance, at the Management Development Institute Gurugram, India. His academic interests are in the inter-disciplinary analyses of public policy processes and institutions, water governance, peri-urban issues and vulnerability and adaptation to environmental change.

Vishal Narain

When we talk of a smart city, what (and whom) do we exclude and include, on what basis, and for which benefits?

Smart cities are coming indeed, but how can they be wise and sustainable? I think this requires challenging some of our commonly held views and notions. First, I find it disorienting that in this age and time, we still talk of a “city”, as if it is some well-defined entity, marked out in space and time. Implicitly, the definition of a city assumes some spatial or administrative unit marked out or posited against a boundary. Typically, we think of a city as the opposite of what is not a city; for instance, and typically of what is “rural”. In the emerging context of the Global South, the urban-rural dichotomy is fast disappearing. We need to reimagine what a city is. Focusing on the city narrowly may mean compromising the integrity of ecosystems that support it, or from which the city draws its resources.

So, when we talk of a smart city, what (and whom) do we exclude and include, and on what basis? Is this the city core, the jurisdiction boundary, or also the peripheries whose resources are guzzled by the growing city? I live in Gurugram, and my residential gated colony is right next to a village settlement area, on whose (former) agricultural land my house is built. Is that village also “city”? The institute where I work, Management Development Institute, shares a boundary wall with a village called Sukhrali, which is now under the Municipal Corporation of Gurgaon. Just as I leave the main gate of the institute, I see rural folk sitting on cots and playing cards while smoking the hookah. (Hookah is a communal pipe. Village folk collectively smoke tobacco, taking turns.) Among them are former farmers, real estate agents, potters, craftsmen, and transport operators. Is my institute located in a city or a village?

In this age and time, when rural-urban boundaries are blurring in the Global South, programmes targeting “rural” or “urban” areas mean little. I would go for “smart watersheds”, or “smart urban agglomerates”, or “smart aquifers”. We need planning entities and approaches that recognize rural-urban relationships, flows of goods and services between rural and urban areas, dynamic and ever-evolving, or the relationships between social and ecological systems.

Having said that, if smart cities are conceptualized the way that they are right now, how can they be safe and sustainable? Where is the role for technology and infrastructure?

Urban farming is a new trend catching on in modern cities. Using the biodegradable wastes of our homes to grow our own vegetables is catching on. This helps in many ways; the domestic kitchen waste is used, it helps us move towards a circular economy. We consume vegetables whose source we know, and we recognize that they are not contaminated by chemical fertilizers and pesticides. There is a great potential for technology (e.g., through Facebook) to connect people who do this, popularize kitchen gardens and inspire those who would want to be inspired. Technology can help us reduce our ecological footprint and move towards a circular economy.

If we widen the notion of the city to include the surrounds and peripheries that feed it, it may make us see the smart city in a new light. This will then translate into improving rural internet connectivity and strengthening initiatives that foster the use of technologies in rural areas to improve access to information and lower transaction costs; for instance, in the Indian context, such initiatives as e-choupals (which uses information technology to provide information to farmers about market prices). It may mean improving rural-urban connectivity (and not just widening highways and building new expressways). This will improve rural communities’ access to modern health care and education and enable better marketing of perishable produce. It will ensure the safety of rural women and widen their access to urban markets.

We should also use modern technology to generate knowledge on and create greater awareness of the extent and impact of the degradation of natural resources like water bodies that smart cities consume, the loss of forest cover, the increase in built-up area and reduction of groundwater recharge. Expanding infrastructure means creating “more of” something. More for some people usually means less for others; violating the norms of intra-generational equity.

about the writer

Pratik Mishra

Pratik Mishra is a PhD Student in Human Geography. His work pursues the urban’s ecological hinterland to find more than just the sheer quantity of resources or waste that the urban expends in its metabolism, and rather the villages and the lives that get entangled in these resource flows. He hopes that these stories will help us understand better the relations between the core and periphery of Indian cities.

Pratik Mishra

The dangers of anti-poor smartness in Indian cities

Smart city policies in India could have much value, but are also very much part of India’s post-developmental neoliberal turn in politics that portends either indifference or active harm for the urban poor.

To be honest, I was disappointed when I found out that “smart cities” existed already as a buzzword in urban governance outside of India. When our Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2015 announced the Smart Cities programme to develop 100 cities in India through better core infrastructures, more information technology solutions in governance, and cleaner, greener surroundings, I beleived he would be the one to bring this term into vogue and give it shape. He is known for inventing new terms and conflating one thing to another (This is not a criticism). Recently in celebrating the progress in Ease of Doing Business rankings, he stated that this jump in ranking also represented a growth in “ease of living” for citizens. Why wouldn’t he just use the existing Human Development Index which ranks India 131 out of 188 countries and target attention at improving there? (This is a criticism).

The Smart City programme in India is one-of-its-kind in terms of not laying down standards for “smartness” a priori. The idea was to look at the projects and ideas urban bodies would propose in their bids and then create standards tailor-made for those projects. Even that ambition was set aside as the Ministry set aside benchmark standards instead relying on a fuzzier liveability index to just rank smart cities that were already smart. To me, this attitude of fuzziness is welcome.

It’s very clear that the smart cities, which are designed as retrofitted, renewed, or greenfield satellites to existing cities, are there to attract investments. Traffic flows, crime detection and efficient utilities are the means to this, objectives biased towards certain classes of citizens. In talking about nature, health and well-being, my argument is on how smart cities could be more pro-poor without suggesting the policy be any more welfarist (in the redistributive sense, as I only wish it would be). Such policies are not new in India; very much part of its post-developmental neoliberal turn in politics portends either indifference or active harm for the urban poor. David Harvey speaks of the “spatial fix” where socio-spatial arrangements like infrastructures are reconfigured in limited geographies to reflect the imperatives of capital. Capital perpetually seeks spatial fixes that would address its crises and contradictions through geographic expansion and commodification of hitherto underdeveloped resources. Using Harvey’s analogy, smart cities provide yet another syringe for capital’s addiction to expanding its frontier across space. Niall Brenner’s writing on the rescaling of state space allows us to articulate how smart cities represent uneven legal regimes and infrastructures typical of an entrepreneurial approach to urban governance rather than a welfarist-one.

These discourses obviously deal a bad hand to the urban poor. However, within these neoliberally-oriented regimes, the academic wisdom that urban researchers repeatedly stumble upon is that the policy and practice most meaningful to the poor is often located in the interstitial and residual spaces of policy. This insight is the veritable mother lode that keeps producing high-quality academic research bringing out different versions of the poor’s complex and entangled negotiations with the state. Political society (Chatterjee), insurgent citizenship (Holston), quiet encroachment of the ordinary (Bayat), occupancy urbanism (Benjamin), etc. all state that the poor, so often unfairly finding themselves on the wrong side of legality, find flexible arrangements, negotiations with street bureaucrats and political patronage relations useful. Subverting policy serves a greater good. Obviously, the rich exploit fuzziness and commit illegalities even more ruthlessly but that is not something to get into now.

Finally, just from my fieldwork which looks at drinking and wastewater canals that service the metabolism of Gurugram city, I present a sort-of-related example. The canals chart their way across many villages as they bring water to the city or take sewage away. They are assumed to be largely inert flows with transmission loss only on account of evaporation for drinking canals, and irrigation is allowed for wastewater canals though not regulated. These flows are anything but inert though, as through seepage, irrigation and theft, they radically impact the lives and livelihoods of farmers and residents in peri-urban villages. In the absence of any laid down rules or water user associations, farmers utilize wastewater from the sewage canals drawing on local historical norms of cooperation to regulate sharing and minimize conflicts. Seepage from the drinking water canals alters the groundwater table in nearby fields, reducing productivity on low-lying adjacent lands but also creating opportunity structures for farmers farther away who benefit from the groundwater. Interestingly, farmers pumping out water helps the canal structure as it reduces pressure from the high water table. A lot of unregulated activity takes place in the backwaters of policy which is simultaneously often arbitrary and unjust but also regulative and beneficial. The smart city approach of strongly attacking transmission losses, surveying water use and imposing top-down regulations, entrusting unaccountable parastatal institutions instead of local government with responsibility is just the prescription for doing more harm than good here.

A Smart Cities Readiness Guide produced by an industry body describes a smart city as “one that knows about itself and makes itself more known to its populace”. I don’t think smart cities would necessarily produce the right kinds of knowledge in their statistics. If the harder institutional, democratic changes won’t be invested in, I hope spatial fixes like smart cities partially fail so it may allow constituency-level negotiations, flexible arrangements and limited surveillance, all of which have enabled the urban poor to exercise their democratic agency. A technocratic operationalization of smart city principles devoid of adequate human interfaces and contextual decision-making (even if such practices often appear to be corrupt) would only further limit the spaces of economic and cultural operation for those already immiserated by urban life.

Leave a Reply