By combining the benefits of structured decision-making with optimization, harnessing the power of markets, and the nuances of human behavior, we can achieve more nature in cities.

Not long ago, cities and nature were usually seen as two separate things. Thankfully nature and cities are now being acknowledged as inextricably linked, and an exciting and expanding movement is emerging to invest in green infrastructure that helps make cities sustainable, resilient, and livable.

Billions are spent annually around the world to support nature in cities. One investment strategy is to protect nature next to cities—creating defined edges or transition zones between developed areas and their surrounding natural areas and working landscapes. Another investment strategy is to integrate nature into cities—purposefully protecting and restoring green infrastructure inside urban areas, including the reuse of vacant and underutilized lands.

Despite the countless opportunities to implement each approach, very little attention has been paid to how cost-effective these investments are and whether governments and communities are getting the most “bang for their buck”. For over 10 years, Dr. Kent Messer (Unidel Howard Cosgrove Chair for the Environment at the University of Delaware and Codirector of the USDA-funded national Center for Behavioral and Experimental Agri-Environmental Research) and I have been on a journey to apply promising approaches that are commonly used in the business world, scientific inquiry, and policymaking areas outside conservation that help ensure more strategic and cost-effective outcomes. We are committed to bridging the “implementation gap” between academia and the conservation profession to use the best available tools from economics, operations research, behavioral science, decision analysis, and computer science to support cost-effective conservation and environmental stewardship of natural resources. We have successfully applied these tools in a variety of project contexts, leading to more strategic conservation, more acres protected, and shrewd use of available financial resources. Now we have completed our new book, The Science of Strategic Conservation: Protecting More with Less, as an effort to help publicize these efforts and scale the core principles of strategic conservation.

Significant advancements have been made in the theory and practice of conservation science to strategically identify the most important urban lands for biodiversity, ecosystem services, and other conservation objectives. Landscape ecology, conservation biology, and land use planning are some of the fundamental disciplines of strategic conservation planning that have been effectively applied to help achieve on-the-ground successes. We have attempted to harness these tools through the development of optimization decision support tools and applied projects that demonstrate how the comprehensive integration of these scientific disciplines into strategic conservation can help ensure the best conservation outcomes at a given level of financial investment—or, how specific conservation goals can be achieved at the lowest possible cost.

As a conservation planner, I am engaged in advancing structured decision-making tools able to quantify the benefits of potential conservation investments that result in better project selection and implementation. As a behavioral economist, Kent is engaged in cutting-edge research and outreach efforts related to efficient and effective environmental conservation. Our book highlights many of these advances in integrating these techniques into a variety of conservation contexts.

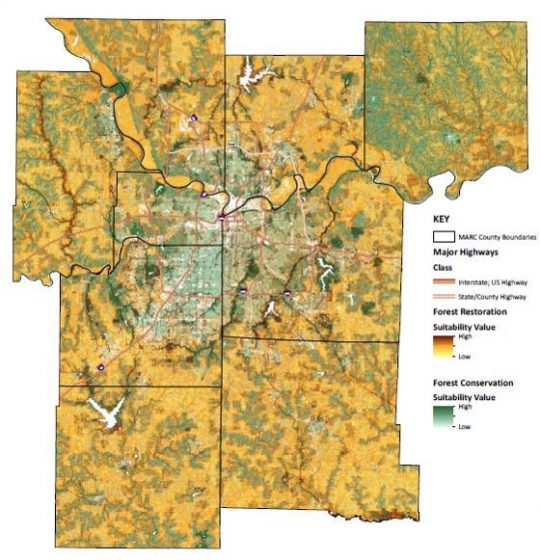

We provide examples in the book on how nature can be incorporated both “next to” and “into” cities. For instance, we showcase the development of regional forest conservation and restoration models for the Mid America Regional Council (MARC). MARC is the Metropolitan Planning Organization for the Kansas City region, so it oversees investments in transportation infrastructure. MARC was interested in forest conservation and restoration opportunities to avoid and minimize potential impacts to forested lands and to identify strategic mitigation opportunities when impacts were unavoidable. We built a GIS model that quantified the benefits of forest conservation and restoration within four categories: clean water (quality and quantity), clean air (carbon storage, pollution), quality of life (recreation, protected lands), and wildlife habitat (green infrastructure network). The resulting maps provided a spatially explicit framework for MARC and other partner organizations to optimize their investments in forest conservation and restoration projects.

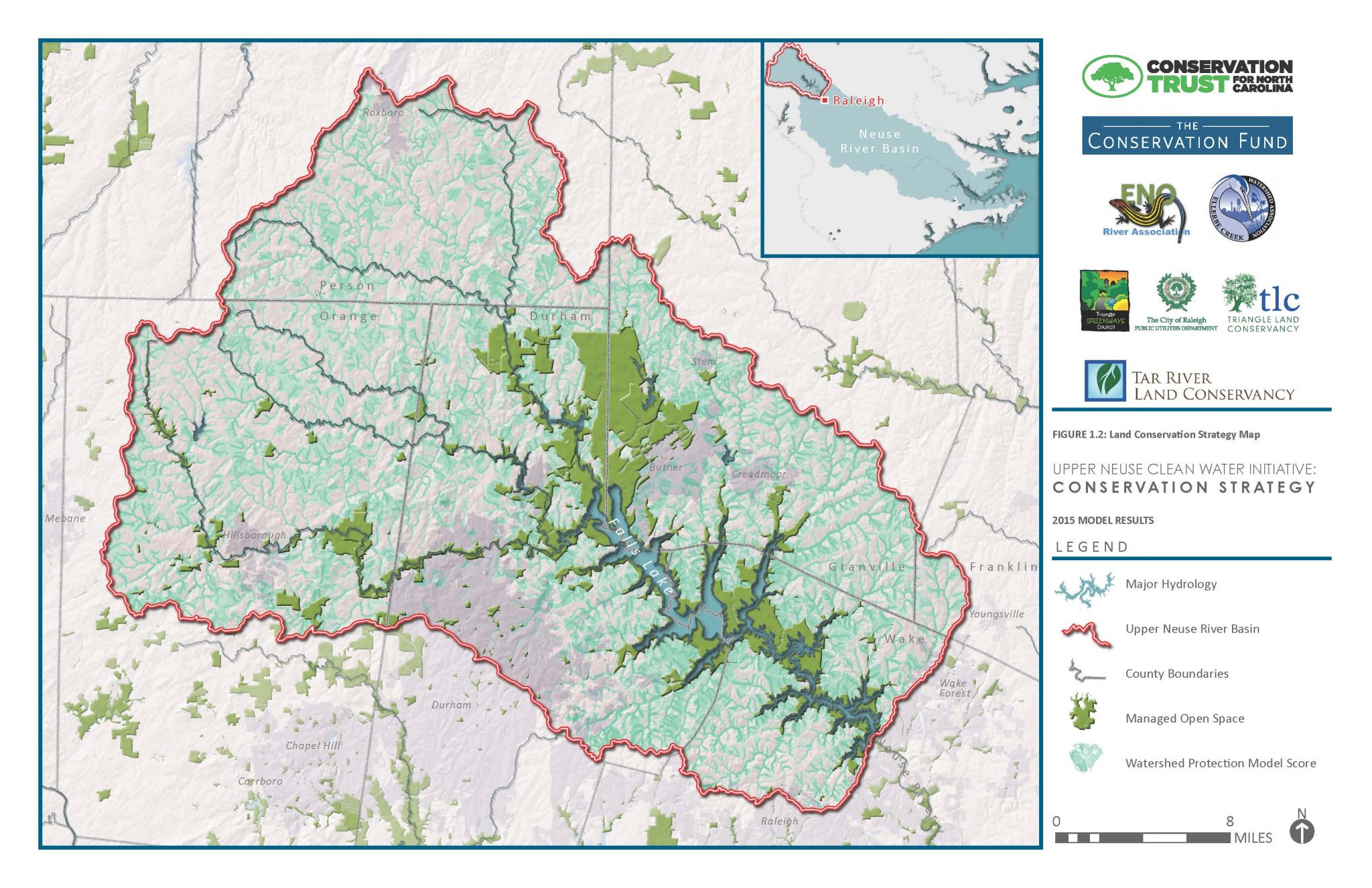

We also showcase how the Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative in North Carolina is using strategic conservation to creatively protect land parcels that support clean drinking water for the region’s municipalities. The Upper Neuse Clean Water Initiative is a collaboration by The Conservation Fund, Ellerbe Creek Watershed Association, Eno River Association, Tar River Land Conservancy, Triangle Greenways Council, Triangle Land Conservancy, local governments, and state agencies and is coordinated by the Conservation Trust for North Carolina. Together with willing landowners, these partners protect natural areas that are critical to the long-term health of drinking water from the Upper Neuse River basin by either purchasing parcels or establishing conservation easements on them. In its first 10 years, the initiative acquired ownership or an easement for 88 properties, protecting 84 miles of stream bank across 7,658 acres. In 2015, the initiative set a goal of protecting 30,000 acres over the next 30 years. We built a GIS model that examined every potential parcel in the watershed using multiple criteria and ultimately identified more than 17,000 parcels totaling more than 260,000 acres that would support the protection goal.

To protect more nature in cities using the science of strategic conservation and cost-effective conservation approaches, it is important to take a multiple benefits approach. For example, urban tree planting programs provide an array of human and natural benefits, including their value in ensuring clean air and clean water as well as providing habitat for wildlife. These ecosystem service benefits can be quantified using a variety of techniques and structured decision-making methodologies. The book illustrates numerous examples of quantifying the value of green infrastructure, including using decentralized stormwater management tools that can capture and absorb rain where it falls, thereby reducing stormwater runoff and improving the health of surrounding waterways.

More nature in cities can be accomplished on the ground by combining the benefits of structured decision making with optimization and the harnessing of the power of markets and the nuances of human behavior. By effectively developing, organizing, and prioritizing decision-making criteria in a structured and consistent way, cost-effective conservation tools can then be applied to get the most “bang for your buck” in an array of nature-based investments.

Will Allen

Chapel Hill

Leave a Reply