“For the child….it is not half as important to know as to feel. If facts are the seeds that later produce knowledge and wisdom, then the emotions and the impressions of the senses are the fertile soil in which the seeds must grow.”

—Rachel Carson, 1965, p.58.

What are the types of childhood experiences that instil a lifelong value for nature and promote stewardship behaviour later in life? It turns out that the sense of wonder that children experience in nature is a crucial factor.

In response, individuals, organisations, and governments globally are devising interventions to reduce or reverse the negative impact of human activities. Several of these interventions are focused on children—the next generation of environmental stewards who will eventually be responsible for curbing human impacts to preserve the natural world. Instilling a genuine value for the natural world during childhood has been shown to motivate environmental stewardship behaviour during adulthood.

But, what types of childhood experiences instil a lifelong value for nature and promote stewardship behaviour later in life? This question has been explored extensively by environmental psychologists and educators. Their research has found that children who experience a sense of wonder through direct contact with nature are more likely to develop a life-long respect and value for the existence of natural areas, the habitats they contain and the species they support.

A sense of wonder

The sense of wonder children experience in nature was initially articulated by Edith Cobb in her book The Ecology of the Imagination of Childhood, where she surmises,

“The child’s sense of wonder, displayed as surprise and joy, is aroused as a response to the mystery of [the] stimulus [of nature] that promises ‘more to come’ of, better still, ‘more to do’ —the power of perceptual participation in the known and unknown”

—Cobb, 1977, p.28.

A sense of wonder is not only inspired by a lush, damp, tropical rainforest bursting with birds’ songs and monkeys’ cries, or a vast savannah occupied by zebras, lions, and birds of prey. While such visions will certainly awaken a sense of wonder in most of us, many experiences closer-to-home can evoke a similar response. Think of a time when you observed a spider building its web, the individual threads glistening in the sunlight, revealing a shape of perfect symmetry. Or, the feeling evoked when witnessing an army of ants marching synchronistically across the ground, carrying more than their body’s weight in food. Or the sensation of an electric storm, the wind and rain on your skin, and the sound of lightening as it cracks across the sky. The quality of the emotions these experiences evoke in us are often inexplicable, yet they leave an impression so deep that they inspire lifelong respect for the world around us, and the existence of life beyond the human domain.

This sense of wonder can be evoked in children when granted the opportunity to experience the vastness of life beyond and despite human activity. This awareness inspires in young children respect and empathy for other species and habitats, and a desire to protect them.

What qualities of nature-based experiences inspire a sense of wonder in children?

Providing opportunities for children to experience nature “in its element” is something that is crucial to establishing a long-lasting value for it. So, how can we support children in experiencing that sense of wonder so they develop empathy, care, and respect for the natural world?

Broadly, the research has shown two qualities of experiences that inspire a sense of wonder in children.

- Quality of the experience

Three qualities of experiences are valuable in instilling a life-long value for nature.

Direct experiences: Where children can touch, see, smell, and hear the unique sensations offered by the natural world.

Autonomous experiences: Play experiences in nature, where children design and direct their activities according to their interests and curiosities is a crucial factor in instilling a lasting awareness and value for the natural world. Encounters with nature that are free of pre-conceived learning objectives and provide time and space for children to engage with nature according to their own curiosities, appear to be central to developing a personal and long-lasting connection with the natural world.

Social or solitary experiences: Interactions in nature with friends, a mentor or a parent who is knowledgeable and passionate about nature can transfer these sentiments to children. However, solitary experiences in nature, where children have unique, personal encounters are also valuable.

- Quality of the natural place

The quality of the natural place is another key determinant of a child’s experience. Children are generally drawn to natural places that contain a diversity of loose-parts and functional affordances as they support a range of play activities, including climbing, exploring, making and building. The diversity of plant and animal species is also important, and this provides children with an opportunity to see, hear, and touch other species in their natural habitat. Opportunities to find and create “special places” that are hidden from the prying eyes of adults are also important components of favourite places for children in middle childhood (8-12 years). These places are generally characterised by natural landmarks or structures that offer seclusion and privacy such as creek beds, rock formations or trees. Essentially, the less curated the natural area, the better for many children.

Interestingly, places that offer rich experiences in diverse natural environments are more likely to stimulate in children a sense of wonder or empathy for nature. Such places allow the child to express a freedom or wildness to explore and grow. Sadly, however, these factors are often missing in children’s play places in modern cities, significantly compromising their experience and appreciation of the natural world.

Child play in today’s cities

The autonomy and independent mobility of children living in cities today have declined substantially over the past few decades due to safety concerns associated with traffic and strangers, and a shift in cultural expectations. For example, in some States in Australia, it is illegal for a child under 12 years of age to roam their neighbourhood unchaperoned. Although aimed at assuaging safety concerns, this policy places considerable pressure on the ability of parents and caregivers to provide their children with opportunities for outdoor, nature-based experiences. Furthermore, where access to natural areas is possible, children are often unable to play independently due to restrictions placed on them by security-conscious adult caregivers.

Moreover, the design of natural areas available to children in cities often fails to provide engaging places for children to explore. Typically, large tracts of open grass, limitations on access to denser vegetation and limited opportunities for climbing or “risky play” make up the urban “playground” in landscaped parks and gardens.

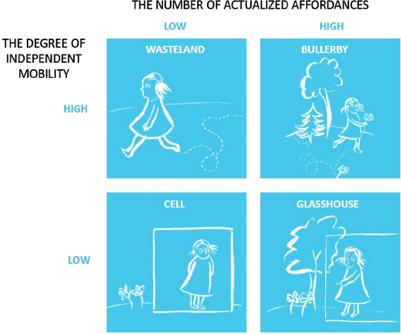

Finnish researcher Marketta Kytta’s categorisation of child-friendly places provides a useful guide to interpret the types of nature-based experiences available to children living in cities (see Figure, right). Kytta’s first category, the Cell, is a situation where children are unable to access outdoor places. In the Glasshouse, children can access an engaging natural area but are unable to engage with it independently because of restrictions placed on them by their adult caregivers. The Wasteland is when children can access an outdoor place, but the quality of the place is compromised and does not offer many opportunities for engaging interactions. The final category is the Bullerby, a Swedish term meaning “noisy village”, and depicts the ideal type of experience when children can interact with engaging outdoor places with high levels of independence.

Over 60 percent of children around the globe live in cities where they face substantial barriers to regular and direct experience of nature. In addition to the numerous implications the absence of nature-based experiences has for the health and development of children, an increasing proportion of children are exhibiting a limited understanding of common plants and animals, as well as a biophobia (“fear” or ambivalence) towards the natural world. It would appear that the future “protectors” of the natural world may be ill-equipped to deal with the challenges. By reflecting more critically on the types of experiences in nature that promote a sense of wonder, perhaps we can enhance formative nature-based experiences for children in cities, and potentially reverse this trend.

Two promising examples

Here we present two promising examples from Australia that are seeking to promote valuable child-nature experiences. The examples are drawn from two different contexts, community-based, and a school setting, to illustrate the range of opportunities available to enrich children’s experiences of nature.

Case Study 1: Parents creating informal nature-play communities

This first example is from Bronwyn Cumbo’s research with children in Sydney, Australia. Bronwyn encountered a group of parents who are taking steps to provide their children with autonomous nature-play experiences in their local neighbourhood. These parents all share a common value for nature instilled through their encounters with nature as children, and a desire to provide their children with similar nature-play experiences. However, the culture of the urban community and safety concerns prevented many of these parents from allowing their children to walk independently or with their friends to the local park to play. To address this, the parents created a regular Friday afternoon “meetup” in a local park after school. These parent meetups were centred around sharing of food and conversation with others in the group. Meanwhile, the children were allowed to roam large distances in the park, unseen by parents, and to engage in a diversity of play activities, many of them that might be considered high-risk by typical urban parents.

Bronwyn’s research revealed two key elements that enabled these rich nature-play experiences to occur. Firstly, all parents shared a common value of nature and risky play, which allowed parents to express their values and provide their children with greater independent mobility than they may in other contexts. Secondly, parents and children had established a set of rules and limitations for their behaviour within this meet-up context.

- Boundaries of independent mobility: Children and parents agreed to boundaries which defined where children could play, and parents could access. The boundaries of children’s play areas were out-of-sight, so parents were required to trust that children would play safely and respect their agreement. Similarly, parents were not allowed to approach or enter a child’s play place unless invited by a child, as a show of respect for the child’s private play activities. Children and parents were able to mingle together at the primary “base” where parents congregated with refreshments.

- Boundaries of play activities: Children were encouraged to engage in a range of risky play activities, as long as children felt comfortable that the activity was within their capacity. Children could work together to support or encourage risky activities, such as helping friends climb trees, or explore new areas, but if children were not comfortable, they were encouraged to express this and for others to respect it.

These children had each established a strong connection with certain areas in the park through their play over time and had a unique ability to collaborate together to solve problems or develop imaginary narratives through their play.

Case study 2: The My Patch Project

The second example is the My Patch Project started by Nel Smit in Tasmania, Australia. In the project, each child chooses a patch of land in a designated area within the school’s vicinity. During the course of a year, the children come to identify with their 1 m2 patch: What are its special features? What are the colors, shapes, textures, and smells? What signs of life are there? How is their patch the same or different to other patches? And how do all these elements and activities in the patch change: day to day, after a dry spell, with the seasons, over the year? The outcomes of the My Patch project are very encouraging. Children develop a strong sense of attachment and stewardship that goes beyond taking care of the land. They develop an engagement with and connectedness to “their patch”—a connectedness to nature. And, whilst adults’ and children’s agendas are packed with extracurricular activities, the patches create a feeling of rest and safety. Children mention how they perceive their patch to be a safe haven, a place to visit when they are feeling sad or need some time to think. The My Patch project demonstrates how a low-cost and easy-to-implement idea can render incredibly important benefits, in the short- and long-term, for both individual child development and as a valuable introduction to school-based nature education. Most importantly, My Patch focusses on the direct engagement of children with nature on an emotional level rather than through objective observations.

“I think I know more about my patch than anyone in the world. There is so much to discover. Every time I visit I find something new.”

—Nel Smit, My Patch (1997)

More Bullerby, please

We started with the question: what are the types of childhood experiences that instil a lifelong value for nature and promote stewardship behaviour later in life? It turns out that the sense of wonder that children experience in nature is a crucial factor. The importance of allowing children greater opportunities to independently explore and play within the wild, “in-between” places of their urban environment cannot be easily dismissed. Our case study examples show that these opportunities can be realized by parents as well as at school.

There is a clear need to make room in our cities for more of Kytta’s Bullerby places to ensure children experience interactions with nature that are outdoors, engaging and afford high levels of independent mobility. If the quality of both place and experience are high, urban children can continue to experience that sense of wonder that “wild” natural places provide.

Bronwyn Cumbo & Marthe Derkzen

Sydney & Amsterdam

about the writer

Marthe Derkzen

Dr. Marthe Derkzen is a researcher and lecturer with the Health and Society chair group. She studies urban nature from a social justice perspective with an interest in climate adaptation, local food, healthy neighborhoods and stewardship of the commons.

References

Broberg, A.K., Kytta, M., Fagerholm N., (2013) Child-friendly urban structures: Bullerby revisited. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 35 (110 – 120)

Carson, R. (1965) The Sense of Wonder, London. United Kingdom. HarperCollins.

Cobb, E. (1977) The Ecology of Imagination in Childhood. New York: Columbia University Press.

Leave a Reply