It is beginning to feel like the anticipated future under climate change is even closer than we once thought. After a particularly harsh hurricane season in North America and following another year of record high global temperatures in 2017, many people recognize that we are entering a new climate reality. Current and projected trends in extreme weather events highlight the need for fundamental and transformative change, to improve living conditions for urban residents.

It seems increasingly clear that urbanization pressures and climate change are on a collision course in cities all over the world. Cities are influenced directly by climate change as they deal with increased extreme weather events such as tropical storms, hurricanes, flooding, heat waves, and prolonged droughts. Therefore, the need for adaptation takes on a particular urgency when it comes to municipal policy. Indeed, municipal governments might be best placed to mobilize resources in the face of sluggish international government agreements and the inaction of their federal counterparts. From coast to coast, municipalities big and small are developing ambitious climate action plans. For example, New York City famously vowed to divest billions of dollars for their pension funds from companies in the fossil fuel industry; San Diego is planning to be 100 percent renewable by 2035; San Francisco announced its plan to honor the Paris Agreement through a combination of strategies to reduce waste, increase sustainable transportation, switch to renewable energy, and improve urban tree canopy; meanwhile, Miami is elevating roads, upgrading stormwater infrastructure, and building sea walls in exposed areas.

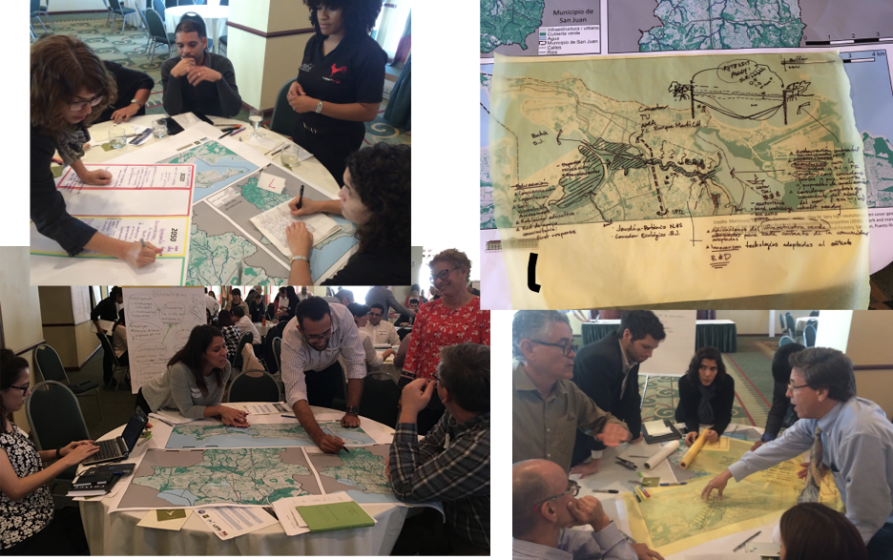

Out of this need emerged the Urban Resilience to Extreme Events Sustainability Research Network (UREx SRN), formed in 2015 with funding from the US National Science Foundation. Bringing together over 100 researchers and practitioners in ten Latin American and North American cities, the UREx SRN’s mission is to build sustainable, resilient, and equitable futures. Working with communities and residents to develop positive visions of the future is a critical component of resilience and sustainability planning, providing an opportunity to step outside the dominant dystopian narratives of our futures and to develop pathways from the present to a good Anthropocene. A keystone of the UREx SRN approach is a series of workshops in each of the network cities, in which scenarios are co-developed. The “movers and shakers” of municipal decision-making are invited, thus bringing together municipal officials, a broad spectrum of civil society groups, community leaders, and sometimes residents. Developing the workshops in partnership with municipal actors who have a pulse on the city allows us to ensure that the scenarios support ongoing processes and future planning. For instance, if a city is extending a light-rail line, we may choose to create a scenario dealing with transit and connectivity to explore the impact of alternative policies. Workshops yield rich data in a variety of formats —maps, timelines, transcripts, narratives, vignettes—from which representations of the future emerge.

We have already completed scenario workshops in San Juan (Puerto Rico), Valdivia (Chile), Harlem (New York), and Hermosillo (Mexico), where a wide variety of positive visions emerged. For example, in San Juan participants envisioned a future of food and energy self-sufficiency for the island; in Harlem residents thought of a future in which their community was resilient to increasingly severe heat waves; in Valdivia participants imagined a new paradigm of “living with water” where people embraced their wetland ecosystems. In the next two years, we will conduct additional workshops with the cities of Phoenix (Arizona), Baltimore (Maryland), Syracuse (New York), Portland (Oregon), and Miami (Florida). Being at the halfway point, it seems fitting to offer some reflection on what we have experienced and learned thus far.

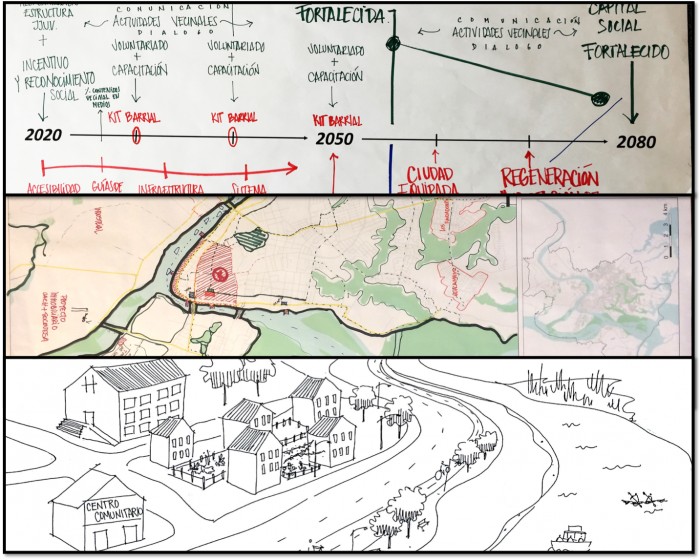

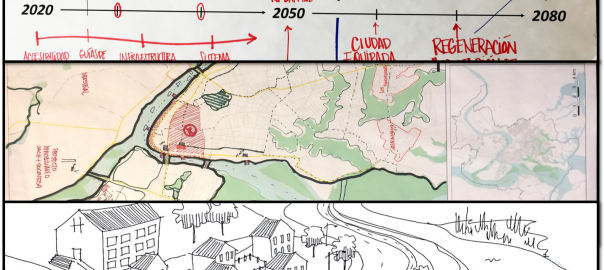

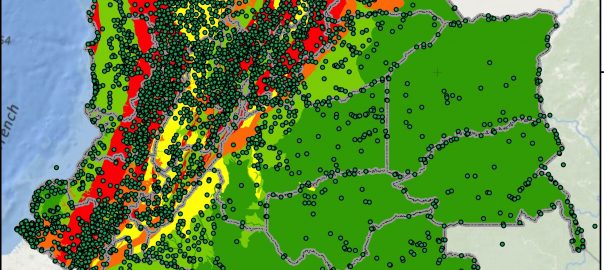

We have learned a lot about workshop design. By now, we have formalized our workflow even though we constantly adjust our activities based on feedback from facilitators. Our day starts with an exploration of historical trends and vulnerability from social, ecological, and technological perspectives. For instance, in our workshop in Hermosillo, we mapped together indicators of social vulnerability, alongside topographical analyses to identify low-lying areas, and information about the size and age of the water pipe infrastructure to show the parts of Hermosillo most vulnerable to urban flooding. Participants are assigned to tables that represent specific city imaginaries that we modify with our local team of city practitioners to make them relevant to their context. For example, the ever-popular green city imaginary might turn into the golden city imaginary for South Phoenix to reflect its desert environment and culture. The day is structured to go from formulating broad aspirations to identifying concrete strategies to developing rich narratives. Activities alternate between formal analytical and informal creative approaches to elicit different kinds of knowledge and information. Our outputs are multidimensional and complex. Building upon the participants’ stated goals and aspirations for their vision, during the workshop participants identify specific strategies to fulfill those goals, they construct timelines to determine when and how strategies will be deployed, draw maps of where they would implement strategies, outline governance actors who will be responsible or affected by the strategies, and finish up the day by creating a narrative about the future of that vision. Following the workshop, dynamic models capture the biophysical dimensions of the changes that stakeholders wish to see in their city. However, models are just one output, other products such as design renderings, vignettes, and qualitative analyses are used to explore the alternative scenario visions.

Our workshops are participatory and, by design, we invite a diverse group of municipal stakeholders to the table. This is our strength and our challenge. It is our strength in that we get a picture of the future that reflects truly interdisciplinary, rich, and nuanced points of view. However, it also presents a challenge. It is our challenge because participants do not have equal footing in the political landscape of their cities and these dynamics carry into our workshops, even when efforts are made to amplify marginalized voices. Furthermore, we recognize our privilege as researchers. Our positionality with respect to these stakeholder groups is sometimes uncomfortable as we find ourselves both confronting and participating in reproducing historical patterns of inequality. Even the very act of thinking about the long-term future can be seen as a privilege of those who have their immediate needs covered. We are also cognizant that the benefits of the workshop and the visioning exercise are likely to be unequally distributed among stakeholders in the room.

Thinking about transformational change is challenging. In our workshops, we have scenarios that are meant to address immediate challenges that cities face—e.g., flooding—and some scenarios that are intended to explore more utopian futures—e.g., a socially just city. We refer to the former as “adaptive scenarios” and the latter as “transformative scenarios”. However, even among the transformative visions, we encounter a lot of shorter-term thinking that fails to challenge the status quo. Myriad factors might explain the lack of more innovative ideas. For example, to push thinking outside of the box, people have to dare to suggest unusual things. It is indeed daring to say unusual things in front of a very diverse group of actors who may or may not know or trust one another. Having more homogenous groups can help participants feel more at ease and reduce fears of ridicule. Yet, the second ingredient of innovation has to do with the idea of “bricolage”, that is, the combining in creative ways things (methods, perspectives, problems, and interventions) that do not often go together. Finding the right mix is very much a work in progress.

So, why do we create these positive visions of the future? Fernando Birri’s[1] words on the need for utopia resonate with our purpose:

“Utopia is something that sits on the horizon. Every time you get ten steps closer, utopia seems to move ten steps further. No matter how much you walk, utopia will always be out of reach. So what’s the point of chasing utopias? Precisely that, it keeps you walking.”

We believe that societies need spaces for radical thinking to confront not only the climate-change challenges of the future but also the present-day conditions that create, reinforce, and reproduce vulnerability. While we feel that our scenario workshops can and should push the boundaries further, they nevertheless serve as spaces to produce complex, richly-described, world-building visions of a future that are full of nuance and tradeoffs. That is, we offer a model to open up the physical and mental spaces to imagine alternatives and to create a solution space where we can question critically the path that we are on. Visualizing positive futures is meant to inspire—but more importantly, it is meant to guide action and forge the necessary alliances to push for change.

Marta Berbés-Blázquez, Tempe, David M. Iwaniec, Atlanta,

Nancy B. Grimm, Phoneix & Timon McPhearson, New York City

about the writer

David Iwaniec

David Iwaniec is Assistant Professor of urban sustainability at the Urban Studies Institute and Andrew Young School of Policy Studies at Georgia State University. His research is focused on the development and application of sustainability and transitions concepts and methods, with an emphasis on urban transformation in transdisciplinary settings.

about the writer

Nancy Grimm

Nancy B. Grimm is an ecologist studying interactions of climate change, human activities, resilience, and biogeochemical processes in urban and stream ecosystems. Grimm was founding director of the Central Arizona–Phoenix LTER, co-directed the Urban Resilience to Extremes Sustainability Research Network, and now co-directs the NATURA and ESSA networks, all focused on solving problems of the Anthropocene, especially in cities. Grimm was President of the Ecological Society of America (ESA) and is a Fellow of AAAS, AGU, ESA, SFS, and a member of the NAS. She has made >200 contributions to the scientific literature with colleagues and students.

about the writer

Timon McPhearson

Dr. Timon McPhearson works with designers, planners, and local government to foster sustainable, resilient and just cities. He is Associate Professor of Urban Ecology and Director of the Urban Systems Lab at The New School and Research Fellow at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies and Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation