about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

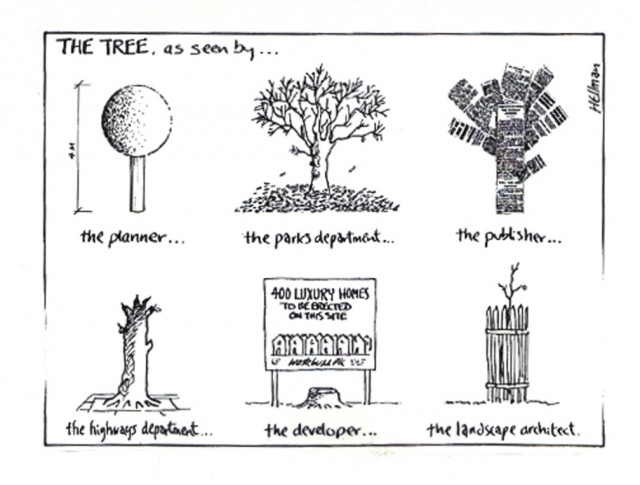

Urban planning (and the city plans that express it) is typically focused on coherently organizing city systems, flows of people and resources, where things are and should be. While parks, green and open spaces are usually part of urban plans (but there are exceptions), ecology and process are on the sidelines.

Much of the writing at TNOC addresses the essential ecological and social values that flow from ecosystem services, green spaces, and biodiversity.

So, should not a greater ecological sophistication be embedded within urban planning?

Should there not be ecologists at the center of urban planning teams in cities?

Of course this requires that ecologists get involved, learn about planning and its methods, and invest in the tradeoffs that are inevitably involved in planning something as complicated as a city.

Where are the examples ecology embedded in urban planning? How can it be done?

about the writer

Will Allen

Will is the Senior Vice President of Strategic Giving & Conservation Services at The Conservation Fund in Chapel Hill, NC. At The Conservation Fund since 1994, he formerly served as the Fund’s director strategic conservation planning and enterprise geospatial services and as an instructor for green infrastructure and conservation GIS training courses.

Will Allen

It is particularly amusing to me to talk about this idea of whether ecology “could” play a bigger role in planning, since that was the primary motivation for me wanting to attend the City and Regional Planning program at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill back in the 1990s in the first place!

My graduate school application essay focused on the concept of sustainable development, and I argued that expanding the use of ecological science into city planning was an essential element in that journey towards sustainability. In undergraduate school at Stanford University, the Urban Studies program exposed me to Ian McHarg’s iconic 1967 book Design with Nature. The book and Ian were the primary reasons that I went into the city and regional planning profession. The book seemed like the fundamental manifestation of what I thought land use and ecological planning should be, where the intrinsic suitability of the land drives the land use tradeoffs between ecology and the built environment.

My graduate studies and professional work at The Conservation Fund have focused on ecological planning with an emphasis on environmental design and sustainable development, in urban and rural environments, and at multiple scales. Inspired by McHarg’s layer cake, I have applied spatial planning using geographic information systems as my fundamental toolbox for thinking about how to protect a city’s green infrastructure and implement a strategic conservation planning approach to our work.

But, I still have a bit of lingering frustration with this topic of ecology and planning. Ian’s book is from 1967. I went to graduate school in the 1990s. It is now 2018. How far have we really come? My short answer is far, but not far enough.

I was reminded of how far we have come, and not come, when I was asked to do a review of the 2016 book entitled Nature and Cities: The Ecological Imperative in Urban Design and Planning by Frederick R. Steiner, George F. Thompson, Armando Carbonell (eds.) from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. The book focuses on the role of landscape architecture and its “ever-expanding role in improving urban settings at every human scale.”

Given the topic, I knew that McHarg would be front and center in many of the essays. Little did I realize, however, that some of the chapters would become a referendum of sorts on the McHargian philosophy. In Richard Weller’s essay entitled: “The City Is Not an Egg: Western Urbanization in Relation to Changing Conceptions of Nature”, Weller identifies what I would call the “McHargian Paradox”—that is, any attempt to apply a prescriptive method to designing with nature in cities is virtually impossible given the complexity of natural systems, functions, and processes that make aspects of nature “unknowable”. In a nutshell, while McHarg focused on biophysical data, landscape urbanists utilized a diversity of data from sciences and liberal arts. This chapter captured the essence of the ongoing tension between urban spatial planning through geographic information systems and the landscape architecture profession. Here I am, a McHarg disciple, but thanks to my primarily practitioner-based career, I did not realize the fierce debate in the academic world over his legacy.

So as I continue to think about ecology and planning with my drink in hand at this very nice bar with nine other planners and urban ecologists, I wonder how the rest of the group now feels about the words “ecology” and “planning” and wonder whether, and how much, they now incorporate concepts of green infrastructure, resiliency, adaptation, biophilia, and system approaches into their thinking, and how that might redefine how they “label” or portray themselves. Time for another round, I suppose!

about the writer

Juan Azcarate

Juan Azcárate is a research at the Humboldt Institute, Colombia, where he works with biodiversity in urban-regional environments. He is an environmental planner with a PhD degree in Land and Water Resources Engineering, and his main interest is to use strategic approaches to enhance decision making and promote pathways towards sustainability.

Juan Azcárate

Many may agree that the base for a great life is a great childhood. And, when talking about urban planning, many may also agree that cities that cater to the needs of children in their planning processes necessarily become, in the long run, livable, attractive and sustainable cities. However, in practice and despite the enormous efforts that have been invested to address the needs of children in urban planning, that is planning for and investing in accessible social infrastructure such as daycares, schools, libraries, museums, hospitals and recreational centers, various gaps and challenges remain to be tackled in this respect.

One such gap, which directly impacts the needs of children in cities, is the failure to include urban green areas and their associated ecosystem services in urban planning processes. A possible reason for this gap is that green areas and the services they provide city inhabitants, in particular children, are often undervalued in city planning processes. It’s here that urban ecology has focused its efforts, aiming to inform planning by designing tools and scientific publications that explore and explain how nature can be environmentally, socially, and economically beneficial for urban well-being and for child development. However, much of the information on the benefits of nature for urban well-being come, in general, from more developed, politically stable, and equitable societies. The relevance and application of this information in developing, more biodiverse, politically unstable and unequitable contexts, such as those typical of Latin America, can be questioned and encounter difficulties.

In this respect, ecology could contribute to urban planning by working to speak a common language and by providing context-specific solutions. This requires that ecologists be prepared to work across disciplines and in different sectors of society. Additionally, it means that they are ready to undertake the promotion and defense of urban biodiversity not only in the social and political realms, but also in the educational realm, where the focus is on developing the capacities and skills of children. Viewed in this respect, addressing cities and education becomes an excellent opportunity and common ground for planners and ecologists to speak the same language and work together to simultaneously plan for greener cities and cities that serve child education.

If this opportunity is made tangible, especially in developing countries where urban environments usually bring together a wide variety of informal capacities, values and human, natural and economic resources, these informal assets can be well planned and managed and cities turned into spaces for innovation, development, research, and education, where ideas and solutions are generated to address different challenges at different scales.

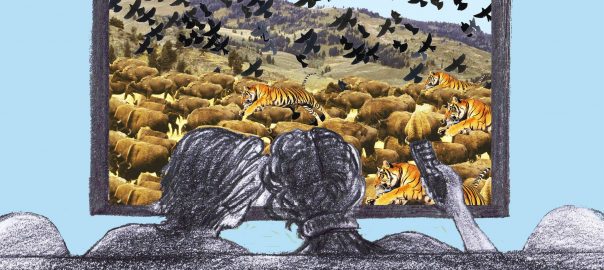

Moreover, in these contexts, it is important that cities complement the formal education that takes place in classrooms. For instance, cities offering an ample provision of urban green areas, such as parks, trees, hills, rivers, and wetlands where activities such as citizen science (e.g. bird observation and monitoring), ecological walks, urban gardening, and ecological restoration can take place, will allow children to come in direct contact with nature and reach a more relevant learning, one that is contextualized and integrated with the realities of their environments and communities.

As spaces of education and innovation, cities should also strive to contain museums of natural history, zoos, botanical gardens and other educational spaces that allow a large number of children to get in touch with and learn from urban nature. With these spaces in place and through the activities that can be developed in them, cities can act as learning rooms, bringing children closer to nature, in this way creating awareness of its importance and at the same time awareness that they are part of urban nature.

Well planned greener cities promote the construction of knowledge and learning in children through the interaction of their socio-cultural and their natural environments, complementing what they have learned passively in classrooms. This to say that cities may favor a socio-ecological learning in children that is fundamental for environmental education and sustainable development.

Despite these potential benefits of cities, the implementation of socio-ecological learning initiatives has been limited to a very local scale, lacking strategic nature, which means that it has not reached change on a scale of political incidence.

It is here where urban ecologists can make a difference in planning, by linking to networks and associations that, for example, carry out these local activities, as well as with universities and local governments who can share these experiences at other scales and with other actors at national and international levels.

In summary then, by taking a socio-ecological approach to child learning and education ecologists and planners may find common ground and an opportunity to jointly contribute to shape more sustainable cities.

about the writer

Amy Chomowicz

Amy Chomowicz is a board member of the Green Roof information Think-tank (GRiT). GRiT is a Portland non-profit that provides education and outreach to support the use of green roofs.

Amy Chomowicz

Planning is, at its core, a human-based and human-focused exercise. Protecting the environment is a priority in urban plans only if people either make the connection between the environment and human health or if people decide “nature” is intrinsically important to them in and of itself. Ecologists can play a critical role in establishing the importance of the environment and in setting a scientific foundation for environmental protection in urban plans.

An ecological framework for planning

The Portland Plan, adopted in 2012, provides a good example of using a policy framework as a building block for a citywide plan. The Portland Plan is a wide sweeping strategy that guides Portland in achieving prosperity, education, health, and equity goals. A group of equity advocates successfully argued for including an equity framework in the Plan. The result is that equity isn’t a stand-alone chapter tacked on at the end of the plan. Equity is infused throughout the entire plan, and it is reflected in the plan’s goals, objectives, and actions. We need the ecological equivalent of the equity framework for all urban plans.

An ecological framework would embed technical information about the environment and ecological processes in an urban plan. An ecological framework would identify the root causes of environmental problems, and it would establish a foundation for planning policies and goals that restore urban ecological systems. By working with ecologists, planners gain the technical understanding of the sources and causes of environmental problems, and they can use this knowledge to develop plans that improve the city’s watersheds, transportation, neighborhoods, and economy.

Another example that addresses the environment and economy comes from the Central City 2035 Plan. The City of Portland is poised to adopt a requirement for green roofs on new construction in the central city. It is doubtful that such a requirement would have made it this far without data and information that assured planners and decision-makers that adding a green roof to new construction is not cost prohibitive.

Role of ecologists

Ecologists play many roles in urban planning. In terms of developing the scientific foundation of urban plans, ecologists play two critical and active roles. First, they assemble and translate data into information that can be readily understood by planners and the general public. Planners can use this information to establish the environment as a priority in urban planning. Data by itself is not very useful to planners, but the story the data tells is critical.

Ecologists also help planners and community members understand the connections between ecological processes and human health. For example, stream hydraulics may affect flooding, property values, and human health and safety. Trees and vegetation affect urban heat island and air quality, two processes that can severely impact human health. The presence of trees is associated with improved student performance on tests and improved birth weights for newborns. Ecologists can provide the data and information that show how these ecological processes benefit or harm human health.

Role of planners

Planners are the unifying tie that brings everyone together. They can draw ecologists into the planning process and provide an avenue for them to share their data and information. Using the ecologists’ story, planners can foster an urgency to prioritize environmental health and they help embed ecological information in urban planning policies and goals.

While urban plans set a course for the future, they must also address restoring damage done by past actions. Looming environmental threats such as climate change, the arrival of invasive plant and insect species, and water scarcity threaten our quality of life. Urban planning plays an ever-increasing role in restoring our cities, and ecologists are essential to establishing the scientific foundation for urban plans.

At the outset, any planning process should establish ecology as a foundational principle on which to base the plan. Planners and ecologists can work together to form the ecological foundation for setting planning policies and goals. When they work together, planners and ecologists learn about each other and how to build on each other’s strengths, and they can help us all gain a more complex understanding of the world we inhabit. In doing so, planners and ecologists together can generate urban plans that move our communities toward greater resiliency that protects the environment and human health.

References

City of Portland, The Portland Plan, http://www.portlandonline.com/portlandplan/index.cfm?c=58776

City of Portland, 2005 Portland Watershed Management Plan

about the writer

Katie Coyne

Katie co-leads the Urban Ecology Studio at Asakura Robinson where she is a passionate advocate for design informed by studying the overlap between social and ecological systems.

Katie Coyne

Right now Austin, Texas is in the midst of an extremely contentious land use code rewrite that does not substantively take into account previous plans. Simultaneously, a number of planning processes are underway that have a direct impact on the City’s land use code and/or future fabric of our City, but there is no clear path to making sure there is synergy among all of those efforts. Because of these disconnects, the City’s Environmental Commission recently passed a resolution that recommended City staff work to align and clearly demonstrate connections and synergies between plans, initiatives, and programs across departments to maximize the collective impact of City initiatives; and, work to align and clearly demonstrate connections and synergies between the above plans and tools and the final draft of the land development code.

The following recent or ongoing planning projects and tools are at various stages of development, each shepherded by a different department or entity:

- Austin Water Forward Master Plan—Austin Water Utility

- Integrated Green Infrastructure Plan—City of Austin Watershed Protection Department

- Functional Green Program—a proposed pilot program housed in the City’s Development Services Department

- Climate Resilience Action Plan—the City’s Office of Sustainability

- Long Range Plan for Land, Facilities and Programs (Long Range Parks Plan)—the City’s Parks and Recreation Department

- Equity Tool—the City’s Equity Office

- Project Connect—CAPMETRO

- Strategic Mobility Plan—the City’s Transportation Department

- Austin Strategic Housing Blueprint—the City’s Neighborhood Housing and Community Development Department

Earlier in 2017, I was a proponent for a resolution adopted by the Austin City Council that directed the Watershed Protection Department to come up with a “plan to plan”, outlining the key items necessary to create the aforementioned Integrated Green Infrastructure Plan (IGIP) – the first of its kind in the state of Texas. At the time I was hopeful that this plan could, in the very least, begin to tie together the mess of plans listed above with existing plans like the City’s Urban Forest Plan. I have been repeatedly assured that this plan will be holistic. However, at a recent meeting a well-meaning individual referred to the IGIP as “watershed’s plan”, only affirming my fears that this will likely become too narrow in focus.

There is no formal structure or incentive in place in the City of Austin to promote inter-departmental coordination and collaboration for plans and programs. Not to say this does not happen at all—many staff members at all levels of various departments recognize this need and do what they can to work together. However, the silos that exist and have been solidified over time and result in plans that are “owned” by single departments. Differential budgets, and the resulting surplus/deficit dynamics between different departments make it even more difficult to ask departments to collaborate more. Some departments are (relatively) flush with funds that allow them to be innovative and take risks on novel projects while the for instance, the Parks and Recreation Department’s line item in the City budget does not even cover deferred maintenance of the City’s parks. There are innovative minds, teams, and leaders in PARD but when out-of-the-box ideas come up (or really, anything that does not fit into the status quo of operations) a common reaction is fear and pessimism about the result—which I can only assume is directly tied to budget anxiety. This has a direct impact on the ecological benefits we could garner from our parks system through thoughtful and innovative urban ecological design and planning.

Two questions to end with:

- Is ecology able to be meaningfully integrated into cities without synergy among plans and departments? Yes. But it takes a lot more folks who know and understand ecology spread across multiple departments to do so and the impact will never be as great compared to a collective effort.

- Could urban ecology be the glue that holds everything together? Yes. Atlanta is working on a City-wide Urban Ecology Framework that makes great strides to connect the dots. In my opinion, short of reimagining the practice of how we manage our City from the top down, an Austin Urban Ecology Framework could be part of the solution if it entailed a combination of Urban Forest, Resilience, Water Supply, Watershed Management, and Green Infrastructure Plans; and meaningfully took into account housing, transit, and equity.

So, what is the next step for planners in Austin, Texas if they are concerned with integrating ecology into planning? Speak up when you see missed opportunities for collaboration. Most of all, in this community, we need to get out of our departmental silos and find the best opportunities for collective impact where we overlap.

There is this great Ani Difranco song called Overlap that goes something like this:

’cause I know there is strength

in the differences between us

and I know there is comfort

where we overlap

I for one would feel a whole lot more comfortable if we overlapped more often.

about the writer

Georgina Cullman

Georgina Cullman, Ph.D. is an Ecologist for New York City's Department of Parks & Recreation. As part of NYC Parks Natural Resources Group, Dr. Cullman conducts research and provides advisement to protect and enhance the city's natural areas and biodiversity.

Georgina Cullman and Lauren Smalls-Mantey

To meet critical social and environmental goals, ecology must play a bigger role in urban planning. First, better integrating “ecology” in planning fulfills our obligation to protect urban biodiversity and minimize impacts on our cities’ nonhuman inhabitants. Second, incorporating ecology into planning can provide “green” solutions to common urban design challenges, including mitigating negative human health impacts from urbanization. Finally, incorporating ecology in city planning can enable city dwellers to connect to the natural world and ensure a constituency for the environment in a majority-urban world. Because ecology is about how living things connect to one another, incorporating ecology into planning necessitates coordination between different agencies. When well instituted, these approaches create robust co-benefits.

In New York City, zoning regulation is a way to conserve biodiversity through urban planning. Four Special Districts in Staten Island and the Bronx have been designated because of their unique geological and biological features. For instance, Staten Island is home to some of the largest and most-vibrant ecosystems in the city, such as the unique serpentine barrens. Currently the Department of City Planning is working with the Department of Parks & Recreation (NYC Parks) and others to revise zoning regulations for these Special Districts. The goal is to conserve existing habitat on private lands, increase connectivity, and enhance buffering of public protected areas. These regulations are still being revised, but will include minimum planting requirements, lot design rules to optimize habitat conservation, and maximum levels of impervious surface. Staten Island in particular is under increasing development pressure. These zoning regulations will be critical to conserving biodiversity on private lands.

Green infrastructure is a major component of New York City’s strategy for managing common urban problems such as stormwater management and the urban heat island effect. For stormwater management, one challenge is the city’s existing infrastructure, approximately 60 percent of which is a combined sewer and stormwater system. On rainy days, New York City’s system is often overwhelmed from the influx of stormwater. Storms release a mix of untreated stormwater and wastewater into the city’s waterways. This negatively impacts water quality and recreational opportunities. In response, New York City’s Department of Environmental Protection, in partnership with NYC Parks, has installed right-of-way rain gardens to help manage stormwater in areas prone to excessive flooding.

The urban heat island effect is an urban challenge exacerbated by climate change that acutely impacts vulnerable populations. In urban centers, increased impervious surfaces and reduced vegetated areas decrease evapotranspiration, a mechanism that leads to cooling. The reintroduction of vegetation through green infrastructure mitigates this effect by increasing the rate of evapotranspiration, increasing the permeable surface area of the city, and providing shade. The Cool Neighborhoods Initiative—a multi-agency heat mitigation plan for New York City—incorporates some of these strategies.

Finally, NYC Parks works to increase access to high-quality green spaces for all New Yorkers. Through the Community Parks Initiative, NYC Parks identified 35 neighborhood parks for targeted investment to meet the needs of a growing population and rectify past under-investment. If successfully implemented, 200,000 residences will be within a ten-minute walk of an improved green-space.

NYC Parks seeks to increase neighborhoods’ environmental stewardship through public programming. The Urban Park Rangers for example, create tailored nature experiences for school groups, families, and adults in their local parks. To encourage stewardship and advocacy at a citywide level and trigger greater investment in natural areas conservation, the Natural Areas Conservancy (NAC) launched NYC Nature Goals 2050. This initiative brought together over 60 organizations and identified 25 measurable and actionable targets under five main goals. The Parks Stewardship team engages New Yorkers through restoration events and trainings while NYC’s Partnerships for Parks provides workshops, grants, and other resources to neighborhood park groups. NYC Parks’ investment in individual volunteers, community groups, and coalition building is a strategy to enlist New Yorkers as advocates for their parks.

Multiple co-benefits flow from integrating ecology into planning. For instance, the revision of Special District zoning regulations will protect biodiversity, reduce stormwater management problems, and retain neighborhood character in the face of development. These comprehensive inter-agency initiatives provide the opportunity for “ecology” to play a central role in creating a shared infrastructure. This meets the needs of the people and biodiversity while enhancing resilience in the face of climate change.

about the writer

Lauren Smalls-Mantey

Lauren Smalls-Mantey, Ph.D is an Environmental Engineer working at the New York City’s Department of Parks and Recreation. As a part of the Division of Forestry, Horticulture, and Natural Resources, Dr. Smalls-Mantey serves as the Urban Heat Resilience Project Coordinator for the Cool Neighborhoods Initiative.

about the writer

PK Das

P.K. Das is popularly known as an Architect-Activist. With an extremely strong emphasis on participatory planning, he hopes to integrate architecture and democracy to bring about desired social changes in the country.

PK Das

Evolving a collective identity

As we have now settled down with drinks to begin our dialogue. May I suggest switching roles, the planners speaking as ecologists and the ecologists as planners? Would you agree that such an approach in our dialogue would strengthen our respect for each other and enable a robust collaborative understanding and endeavor for the achievement of a sustainable future?

Isn’t it strange, though not surprising, as to how we specialists are categorized and divided, as much as people and places are constantly divided in the neo-liberalized and privatized world. Planners and ecologists too are assumed to be two separate and independent groups with a skewed assumption that matters relating to nature and environment rest exclusively in ecologists domain and planners are outside that. Shouldn’t planning include and reflect matters relating to environment and ecology? Shouldn’t ecologists engage actively with planning ideas and practices? Haven’t we come to a stage when unification of knowledge and exclusive domains ought to be intertwined producing a paradigm shift in the way we think and understand and classify various matters pertaining to the sustainability question?

That only select individuals and groups have colonised or been trained to colonise the ecologist’s identity is a matter of concern. Similarly the planners, besides lip service, have stood far away from dealing with critical ecological and environmental concerns. The fact is that nature in all its manifestations coupled with human development needs and aspirations ought to be referred to as ecology. This ought to be our worldview and must form the basis for the constitution of a collective identity. For such de-colonisation and comprehension would contribute significantly to the success of a sustainable ecology mission. Also, such de-colonisation would help in breaking the multiple barriers between people and the dominant mindset of segregation between development demands and nature, thereby enabling the democratization of ideas, plans and actions in wider environmental interest.

So lets begin our discussion admitting that the failure to achieve sustainable ecology is a challenge to our collective capacity, capability and knowledge sharing ability across multi-sectorial concerns.

The question that then comes up before us is why just us two select groups? Why aren’t we talking to other diverse people and contributing to wider public engagement and participation, undertaking active public campaign and dialogue? How can public action be mobilized, knowing that is what deeply influences decisions that governments take? How can the idea of sustainable ecology be popular knowledge, going far beyond the short-term daily life needs and demands however important they may be? Our real challenge rests in our ability to break these multiple barriers that we have over time consistently built that have severed the intricate and intimate relationships at all levels that existed.

De-colonisation of knowledge and exclusive domains is the single most difficult task for us, the various segregated “experts” or “specialists”. It would destabilize us in many different ways—settled positions, complacence and our professional arrogance. Similarly, it is the larger phenomenon of constant division and fragmentation of towns and cities that worry us, for that too influences the expert’s individualism. It is the individualism and self-gratification that stand in the way of integration and unification of people and places. We have realized how free-markets and privatization thrust under neo-liberalization and globalization have systematically promoted individualism and self-gratification, thus compelling us to intervene in the current political trend.

Therefore, It is crucial to consider and elaborate the ideas of sustainable ecology as fundamentally being a part of social and political construct. This is to go beyond the stereotypical understanding of many governments and experts in territorializing and barricading natural elements and areas for their protection and conservation. Ecology as a complex cocktail of natural and built environments and a way forward for their integration and unification are indeed our collective priority.

Natural elements and areas have been constantly abused, attacked, damaged, and totally destroyed across vast areas. Land and environment have been damaged to an extent that they have lost their regenerative capacity. As a result, human habitat is under critical threat. Living in towns and cities are increasingly becoming unsustainable, posing a threat to health and wellbeing.

The world over, across nations, we have attempted to confront and tame nature and natural forces, exhibiting our arrogance and power, sadly to miserable defeat every time. Yet we continue with similar effort while pursuing various projects under the guise of development. Governments and the ruling classes continue to plan and implement environmentally disastrous works, be they indiscriminate landfilling, destruction of mangroves, diversion of rivers and landfilling natural river beds, depleting forests, and so on. Build more syndromes led by real estate short-term interest is aggressively pursued with active government support, in spite of those projects in no way fulfilling the larger public interest.

Our challenge is to rebuild with nature and stop defying it. This would mean to re-envision our towns and cities and a paradigm shift in the way various works or projects are conceived and implemented. This would mean that many sections of our cities and towns would have to be done away with or remodeled from their established forms and locations to new ones. We have to together work towards gradually turning around our cities. Let us as a motley group of ecologists in this bar begin our work together by undertaking the task of preparing maps of our towns and cities for a sustainable future. This along with repairing, restoring, reclaiming, conserving, and nourishing all natural areas, elements, and conditions would have to be the immediate action plan.

Natural areas along with the necessary buffer have to be collaboratively mapped and open data relating to ecological relationships, including those that existed, would have to be registered. Development works have to be planned and implemented in response to all of these natural conditions. Re-establishing the ecological networks and relationships, including new ones, would form the basis of land use planning and development works. Carefully scheduled phased implementation based in such a new imagination has to be evolved and aggressively pursued with wider public consultation. There is no alternative but the ecologists together steering a campaign towards the democratization and achievement of this objective.

about the writer

David Goode

David Goode has over 40 years experience working in both central and local government in the UK and an international reputation for environmental projects, ranging from wetland conservation to urban sustainability.

David Goode

From black hole to city metabolism: collaboration is crucial

Oh no not again! We have been through this so many times during the past fifty years. In the 1970s the UK Government led an investigation into the relationship between ecology and planning which concluded that there was a black hole between the two. The two disciplines have developed from very different roots. One is essentially a science, devoted to understanding how the natural world operates. The other is a process, aimed to fulfil people’s needs in the most effective way. In the 1970s they didn’t talk to each other very much. Planners complained that they didn’t understand ecologists because their reports were full of Latin names, with little explanation of context or significance. In fact, they each have their own language and philosophical standpoint. Ecologists found it equally difficult to know what kind of advice planners really needed. We needed to talk together far more.

In 1982 I found myself in a more productive situation when I was appointed as senior ecologist in the Greater London Council’s strategic planning team. It was my job to produce a set of ecological policies, which would form a crucial part of a revised development plan for the capital. Working with planners to produce policies that would then be implemented was very satisfying. One of the policies relating to flood alleviation stated that “…the Council will define the floodplains of the Thames and its tributaries to be safeguarded from development and London borough councils must accordingly further the protection of these areas through their local plans and in development control.” Another stated that, “there will be a presumption against development within Sites of Special Scientific Interest, statutory Local Nature Reserves and other ecologically sensitive areas.” This was at a time when there was no mention of either ecology or nature conservation in the existing London development plan.

The ecological policies needed to be defined unambiguously as a basis for strategic planning, and they needed to have strong political support. We certainly had that support and alongside it we had the benefit of a groundswell of public support for ecological issues. But I was always conscious that those of us practising as ecologists tended to be regarded as rather second rate in comparison with other land management professions. We didn’t have a Professional Institute of Ecology. Yes the UK had the first Ecological Society in the World, but that was principally an academic body for the study of ecological science. We needed an Institute equivalent to those of planners, architects and surveyors. So a few of the leading practitioners in ecology promoted the idea in the late eighties with the result that the Institute of Ecology and Environmental management was launched in 1991. It has recently gained a Royal Charter which gives practising ecologists similar standing to that of other professions.

There are still antagonisms. Many planners and developers faced with protected species on a high value development site can only see ecology as presenting problems in terms of time-scale and cost. Sadly the benefits of nature are not the first thing they see. But there are some splendid examples where a local planning department has seen an opportunity to cater for nature, rather than see it as a problem. South Cambridgeshire District Council won the best practice award from the Institute of Ecology in 2011 for a village project called Saving the Fulbourne Swifts. All they did was to require nesting boxes for swifts to be built into a large number of newly built houses. Local residents loved the result. The developers are responding too. I am told that one house builder has been so impressed by the positive effect of new natural landscapes, in terms of the public response and possibly also the increased value of the properties, that they now intend to create such landscapes for all their housing schemes.

I believe that the increased stature of ecology and ecologists through having a Royal Charter has had a very positive effect on our ability to promote ecological solutions to deal with some of the key issues facing us today. Planners can no longer be unaware of global climate change. The past twenty years has seen the production of numerous action plans to reduce the impact of climate change on big cities, especially coastal cities. Adaptation options have been considered in considerable detail and it is becoming normal practice for this to be done on a multidisciplinary basis. Ecologists, planners, economists, insurers, and climate scientists work together to find the best possible solutions, based on current scenarios. Ideas that were first promoted by ecologists during the early 1990s, and quite often ridiculed at that time, are now being applied as mainstream solutions by a new breed of ecologist, very often working in collaboration with urban designers, architects, and planners. Green roofs, vertical water gardens, and sustainable drainage schemes are all part of this new urban landscape.

The recognition that natural landscapes within towns and cities provide valuable ecosystem services has already brought ecological knowledge to the forefront in urban design, confirming the need for collaborative approaches. The benefits of natural landscapes are not restricted to ameliorating physical factors, such as ambient temperature, humidity, and flooding. The health benefits of biodiversity to city people are becoming well established, affecting both physical and mental health. The ecology of a city is becoming recognised as crucially important.

But I can also see a time when city planning as a whole will be based on ecological principles. Understanding the metabolism of a city, how materials and energy move through the system, is no different from the natural world. Ecologists are well versed in this kind of approach. It is only a small step from understanding city metabolism to utilising that knowledge in designing a truly smart city. I believe ecologists will have a major role to play in creating our future cities. The ecologists may well replace today’s planners.

I would enjoy discussing that with the planners.

about the writer

Mark Hostetler

Dr. Mark Hostetler conducts research and outreach on how urban landscapes could be designed and managed to conserve biodiversity. He conducts a national continuing education course on conserving biodiversity in subdivision development, and published a book, The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development.

Mark Hostetler

Conserving Trees and Services: Urban trees can provide many valuable services beyond just wildlife habitat. For example, trees reduce stormwater flow by intercepting a portion of the rain when it hits leaves, branches, and trunks. This can be a significant savings; for example, in the metropolitan Washington DC region, the existing 46 percent tree canopy reduces the need for stormwater retention structures by 949 million cubic feet, valued at $4.7 billion per 20-year construction cycle (based on a $5/cubic foot construction cost)[2]. Trees also benefit air quality as they remove many pollutants from the atmosphere, including nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), ozone (O2), and carbon monoxide (CO). Tree cover reduces energy costs significantly; American Forests found that tree cover in the Atlanta area saved residents approximately $2.8 million annually in reduced energy costs[3].

Natural areas provide shared green space for humans to interact and recreate. Creating green infrastructure, in terms of pocket and natural parks, creates a strong sense of place for residents by incorporating green space and walkability into their designs. This allows residents an opportunity to socialize and watch wildlife in its natural setting. A study found that a sense of place, attachment, and satisfaction were affected by not only social constructions but also the landscape attributes of the natural environment[4]. Many feel that the conventional designs, without walkable neighborhoods or green space, are counterproductive to an individual’s need to experience community[5] and urban residents really desire a sense of community[6]. Nearby natural areas are often used to educate people about their environment and human history. A recent study found that unstructured natural areas helped children, later in life; they had more positive perceptions of natural environments and outdoor recreation activities[7].

Preserved natural areas can increase property values. Most homeowners view healthy natural communities within close proximity to homes as aesthetically pleasing. This translates to an economic value of green space[8]:

-

- “The home-buyer, speaking…through the marketplace, appears to have demonstrated a greater desire for a home with access…to permanently protected land, than for one located on a bigger lot, but without the open-space amenity.”

- “Top rank of open space/parks/recreation among factors used by small businesses in choosing a new business location.”

- “Percentage of Denver residents who in 1980 said they would pay more to live near a greenbelt or park: 16 percent. Percentage who said so in 1990: 48 percent.”

Preserving natural habitats can decrease irrigation costs. Native plants have adapted to an area’s annual cycling of wet and dry seasons. By reducing the amount of formal landscaping and preserving natural areas, cities can reduce or eliminate the need for supplemental irrigation. This saves money for cities.

Interaction with natural areas promotes better human health. There is a growing body of evidence that one’s psychological and physical well-being is rooted in one’s connection to nature. Conversations about “biophilia” and “deep ecology” discuss the intricate link between nature and humans.[9] Even though many people live in urban environments, and most of their lives are spent in cars, homes, and other buildings, their emotional well-being and health depends on their ability to experience nature. The ways in which cities are built and maintained have direct and indirect consequences for natural environments and human health. People recover from stress more quickly when exposed to natural vegetation instead of urban settings[10]. It is especially important that children play outside. A 2003 Environment and Behavior article found that access to natural areas protects children from the impact of life stress[11]. Stress levels were reduced as kids spent more time playing outside, and this protective buffering intensifies with increasing stress levels within children. Furthermore, the amount of time spent in contact with nature affects a variety of human health factors, such as the level of cognitive functioning[12], the number of physical ailments[13], and the speed of recovery from illness[14].

In summary, planning goals that address healthy, livable cities naturally should include ecology and the conservation of plant and animal communities. I would wager that the diversity of plants and animals is highly correlated to the health and well-being of people within cities.

Notes:

[1] Hostetler, M. 2012. The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

[2] Source http://www.americanforests.org/resources/urbanforests/naturevalue.php

[3] Source http://www.americanforests.org/resources/urbanforests/naturevalue.php

[4] Stedman, R. C. 2003. Is it really just a social construction? The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Society & Natural Resources 16: 671-685.

[5] Benfield, K. F., Raimi, M. D., & Chen, D. D. (1999). Once there were greenfields: How urban sprawl is undermining America’s environment, economy, and social fabric. Natural Resource Defense Council.

[6] Brown, B. B., Burton, J. R., & Sweaney, A. L. (1998). Neighbors, households and front porches: New Urbanist community tool or mere nostalgia? Environment and Behavior, 30, 579-601

[7] Bixler, R.D., Floyd, M.F., and W.E. Hammitt. 2002. Environmental socialization – Quantitative tests of the childhood play hypothesis. Environment and Behavior 34(6): 795-818.

[8] Source – Trust for Public Land – https://www.tpl.org/economic-benefits-parks-and-open-space-1999#sm.000q846xjt0ucuv108o2l4few03yr

[9] Wilson, E.O., and S.R. Kellert. 1995. The Biophilia Hypothesis. Washington, DC: Island Press.

[10] Ulrich, R.S., R.F. Simons, B.D. Losito, E. Fiorito, M.A. Miles, and M. Zelson. “Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments.”Journal of Environmental Psychology 11(3): 201–230.

[11] Wells, N.M., and G.W. Evans. 2003. “Nearby nature: A buffer of life stress among rural children.” Environment and Behavior 35:311–330.

[12] Kaplan, R., and S. Kaplan. 1989. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective.New York: Cambridge University Press.

[13] Moore, E.O. 1981. “A prison environment’s effect on health care service demands.”

Journal of Environmental Systems 11:17–34.

[14] Ulrich, R.S. 1984. “View through a window may influence recovery from surgery.”

Science 224:420–421.

about the writer

Elsa Limasset

Elsa Limasset is an environmental engineer at the French national Geological survey (BRGM), based in Orléans in France. She works within the contaminated land team in the department of Environment and Ecotechnology.

Elsa Limasset

Bringing nature into urban planning, hoping to bring more benefits for people, biodiversity, or even the economy, first requires that cities make a place for nature. Indeed, to make that possible, ecologists and ecology must have a bigger role in urban planning and land use regeneration, especially in assisting in a routine assessment of these benefits.

There are already some cities that have integrated the importance of assessing the ecological and social values that come with nature-based solutions. In France, for example, the regeneration of a former military site in Anger city into a combined residential and green innovative landscape has been assessed on such grounds (Ilot Desjardins area). The city has made an effort to evaluate the new developments looking at, for example, its functionality, its accessibility, its capacity for environmental regulation (e.g., ground infiltration capacity), and ecological continuity. Some of the assessed criteria such as aesthetic and effective use were based on the appreciation of local people. Despite more and more French cities demonstrating an interest in the concept of ecosystem services and their evaluation, such considerations are not systematic and no common national framework is yet ready to be proposed. Also, one difficulty in this, is that, conflicts may appear among stakeholders, if expecting different services from the same “system”.

Another specialist that should come and support the urban ecologist is the “soil scientist”. One may forget, but cities and especially nature, or landscaped areas rely on soils. Because their genesis is a very slow process, soils are an unrenewable resource at the time scale of Human being. They are both a supporting element and an inherent component of urban sites and landscape in general. They are fully part of the environment and must be considered when trying to maintain or implant nature in cities. Indeed, soil is also the support for biodiversity, trees, and the fauna that inhabit it. However, if ecology is an afterthought, it can be difficult to create durable co-habitation. One should also have in mind that the long-term soil productivity for a specific plant can decrease with time due the progressive acidification and leaching by rainfall. This is a naturally occurring process, which oblige for example, French farmers to lime regularly the top horizon of their soils to maintain pH near neutral value. Then, soils should be considered as dynamic systems with functions that can change overtime.

Karlen et al. (1997) defined the quality of a soil as “the capacity of a specific kind of soil to function, within natural or managed ecosystem boundaries, to sustain plant and animal productivity, maintain or enhance water and air quality, and support human health and habitation.” It is only in recent years that soil scientists have been taking an interest in the (multi)functionalities of soils in urban areas (in contrast to the importance of agricultural soils that have had more attention), their quality their diversity and the use society is making from them.

Of course, soil has a fundamental role in city planning processes and “expected services” in general. Indeed, planners rely on some major soil functions such as “sealed soils” for roads, “engineering soil properties” for supporting buildings, or simply “constructed soils” for green infrastructures, such as parks, street trees…However other soil functions are becoming of interest, such as “fertility” for urban agriculture that is becoming more and more popular. Also, soil is a fundamental component of continental water cycles. It could contribute to sustainable urban drainage management by encouraging rainwater to infiltrate and recharge groundwater resources (by limiting impermeable surfaces), but also to the regulation of surface water by limiting flooding. Some cities have been rethinking water infiltration and recharge of groundwater, removing existing impermeable surfaces for the benefit of sand, gravel or grass in some areas. Another function of interest for city planners in the context of urban redevelopment, is that soils can have the capacity to retain or degrade some contaminants depending on its chemical and biological composition. Finally, soils are also a sink or a source of calories and can be used as heat exchanger, cooling or heating surrounding buildings.

Therefore, soil functions other than as a support for buildings are the foundation for maintaining or implanting nature or sustaining other services in cities. Soil scientists, urban hydrologists, geo-microbiologists, and ecologists should be definitely involved with planners to enhance soil use, and service provision by understanding, which soil functions, would be mobilised, preserved or reconstructed when feasible. This new way of co-working is fundamental and will make its way forward in cities with the understanding that soil is not a finite resource, and the need to protect its multi-functionality. In France, some cities would be really keen to integrate “soil ecosystem” services into their planning strategies, and rely on R&D to find solutions.

Of course, among all indicators that scientists and planners should define together, i.e. to help showing benefits associated with soil ecosystem services, financial cost is a major one. Also, recent Legislation (Loi ALUR 2014) is pushing for regenerating the cities and limiting urban sprawl. This steers to rethink the cities, and by doing so, to make planners, developers finally aware that if trying to get nature back in town in a sustainable way – as this is a growing demand – , they definitely need to understand and integrate soil in the picture. Efforts ought to be done for example to better quantify the gain that could be made with soil “re-functionalisation”, especially if it helps bringing back the nature in some degraded areas. Last but not least—we could go even further, hoping that in the near future urban areas would have to adapt to nature rather than nature to cities!

Suggesting readings:

2014 Plante&Cité et Val’Hor les bienfaits du vegetal en ville –etude des travaux scientifiques et méthode d’analyse.

2017 M.J. Levin, K.H.J Kim, J.L. Morel, W. Burghardt, P. Charzynksi, R.K. Shaw, IUSS Working group SUITMA Soils within cities – global approaches to their sustainable management SUITMA

about the writer

Ragene Palma

Ragene Palma is a Filipino urbanist currently studying International Planning at the University of Westminster, London, as a Chevening scholar. Follow her work at littlemissurbanite.com.

Ragene Palma

Paradise and wasteland: The importance of ecology in island planning

In an archipelago such as the Philippines, there can be no real planning without involving ecology. Let’s take an example of an island, which involves the issues of tourism, carrying capacity, waste management, and socio-economic implications: Boracay Island.

The case of Boracay

Boracay used to be one of the Philippines’ most pristine islands. Its powder white sand and clear blue waters made it a paradise to the island locals and the rest of the world. Since the island’s boom in the 1970s, Boracay rapidly drew tourists and steadily urbanized to cater to the international market.

Urbanization coupled with a lack of planning and management, especially in the case of an island with limited land and resources, leads to inevitable ecological consequences. In 1997, a glaring drop of tourist arrivals due to findings of coliform bacteria in Boracay pressured the government and private sector to establish a sewage treatment plant, a solid waste disposal system, and a potable water supply system. In the same year, Ecoplan International, Inc. provided an assessment on the island’s carrying capacity, concluding how in that year, carrying capacities had exceeded thresholds, and that trends (including physical elements, transport, tourist perceptions, etc.) were already unsustainable.

To date, in 2018—more than twenty years after the realization that Boracay was in danger, fecal coliform is still a problem, with “contaminated surface runoff” affecting the coastal waters. “Alarming” coral deterioration and excessive algae growth have also followed suit. The 25,000-person carrying capacity of the island is far exceeded by its 75,000-person tourist-inhabitant state. This is despite multi-decade efforts, such as the island’s declaration as a special tourism zone and national government control.

While efforts are now being announced to address the decades-long issues—a six-month closure of the island (that poses displacement and economic degradation), better wastewater services and sewage systems, needed legislation, and a “masterplan” following numerous other masterplans that were not implemented—we see here how glaring the presence of ecological perspective in planning and developing islands is. The New York Times, way back in 1996, phrased the debate between the economy and the environment pointedly: “…economic progress is fighting with ecology as the Philippines struggles to raise living standards for its population and catch up with booming Asian neighbors.”

Including ecology in planning, and more

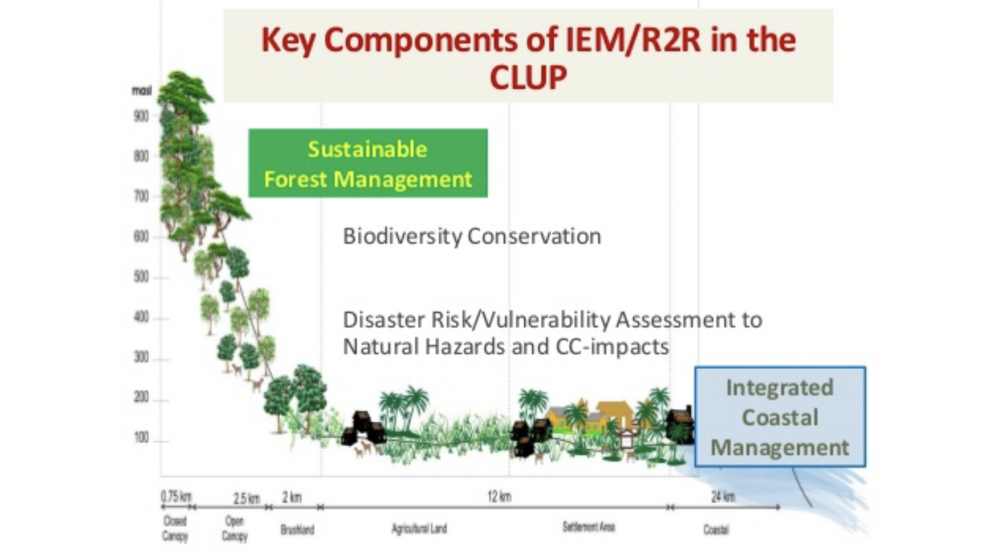

In 2014, the Housing and Land Use Regulatory Board (HLURB) issued the guidelines for land use in the Philippines, integrating ecology in the planning process for cities and municipalities. It provided for a reef-to-ridge basis, making profiles and plans inclusive of all types of ecosystems, adequate for islands and coastal areas. This has created more awareness for planners and general stakeholders to consider environmental impacts and consequences, of development, making Philippine planning closer to the upfront natural resources instead of simply conducting planning on maps and political documents.

The ecosystem-based management is a good start and has yet to be realised in the case of Boracay’s planning. Putting ecology first in environmental and urban planning is, indeed, vital to the implementation of development plans, progress, and long-term sustainability.

But it is not only in the field of urban and environmental planning that ecology should be a part. For Boracay, this opens doors for governance, legislation, and the tourism industry to truly embrace what ecological tourism (or ecotourism) really means and move away from its reality which is currently an irony. An ecological perspective towards planning has also paved the way for the Philippines to integrate climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction in environmental planning.

Ecology’s importance cannot be stressed enough in planning—it is critical to the country’s many islands in determining if, in the long-run, we would be able to retain the paradise we are blessed with or be left with wastelands.

References:

(2018, February 13). What Went Before: Boracay’s environmental issues. The Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved from http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/968277/what-went-before-boracays-environmental-issues

Palabrica, R. J. (2018, April 16). Carrying capacity of tourist sites. The Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved from http://business.inquirer.net/249238/carrying-capacity-tourist-sites#ixzz5CpKRF51a

Burgos, N. P. Jr., (2015, February 20). Boracay coliform level prompts DENR warning. The Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved from http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/674082/boracay-coliform-level-prompts-denr-warning

about the writer

Diane Pataki

Diane Pataki is a Professor of Biological Sciences, an Adjunct Professor of City & Metropolitan Planning, and Associate Vice President for Research at the University of Utah. She studies the role of urban landscaping and forestry in the socioecology of cities.]

Diane Pataki

One way that planners need to change to work with ecologists, and one way that ecologists need to change to work with planners

Ecologists can be downers: I think many early collaborations between ecologists and planners get stymied because ecologists are pretty typical scientists. We’ve been taught to focus on uncertainty and to test assumptions about how urban greenspace really works or doesn’t work for cities. The truth is that much of what we think we “know” about how urban nature can contribute to better, more livable cities is untested. And some assumptions about how nature works in cities have actually been proven to be false. For example, ecological research has shown that there are few scenarios in which urban greening programs can appreciably mitigate urban greenhouse gas emissions. The empirical evidence for using urban greening to mitigate other pollutants such as PM 2.5 is also much weaker than commonly believed. Discussions of using urban trees, for example, to sequester carbon or mitigate poor air quality are often wildly optimistic relative to our basic scientific understanding of what’s really possible.

This kind of negative feedback for urban greening planners and managers is not often well-received, in my experience, but it still has major policy implications. Together, we all need to discuss recent findings that show that urban greenspace rarely has the much-anticipated pollution mitigation effects that people were hoping for. One conclusion is that programs to reduce urban pollution need to focus on reducing emissions. This is a critical finding for highly polluted cities where air quality is a matter of life and death. (I live in such a city—Salt Lake City rivals the world’s most polluted cities for particulate pollution.) But it’s also just one example of how the sometimes less-than-sunny messages of scientists are needed to make urban policy effective.

Therefore, my first “demand” is that planners be willing to let science overturn convention when empirical data disprove deeply held assumptions. But that doesn’t mean that ecologists don’t need to change as well. There’s more potential for scientists to go beyond simply testing basic assumptions about urban nature. In fact:

Ecologists need help to be more visionary: Having that said, ecologists can get stuck in an overly “critical” mode, and it can be hard to get them unstuck, even when it might greatly benefit cities to incorporate visionary science into urban planning. Ecologists are trained to recognize problems and understand the world they see around them, but they’re not really trained to build, design, or create new things. In fact, many ecologists have an aversion to the notion of building, creating, or designing ecosystems, other than for the purpose of restoring the natural ecosystems that pre-dated cities. The result is that radical new ideas about how to make cities better don’t tend to originate in ecological science, especially right now when scientific visions of the future are not as optimistic as they once were.

So far, it’s been easier to keep ecologists out of the process than to help them transition into thinking more like planners who need to transform, and not just understand, the environment. I totally understand why that’s the case, but there could be great benefits to working with ecologists to help transition them into a more prescriptive mindset, so that they’re willing to put science to the task of envisioning and testing new and exciting outcomes for cities. In my view, we’ve only scratched the surface of how we might apply ecological knowledge to plan better cities. To think big, we’ll need answers to questions such as: what’s the maximum ecological capacity of increasing greenspace as cities densify? What specific types and configurations of nature would most benefit different communities? If we free ourselves from the constraints of current cities and think about novel configurations—extensive green roofs and green walls, corridors, terraces, or other new structural and design solutions—how can we implement these solutions at scale so that they’re not highly resource intensive? What types and magnitudes of biodiversity can they support relative to what’s needed to achieve different goals? Ecologists are not, on the whole, thinking about these questions now, but they have the tools and expertise to address them if they can work in partnership with planners.

That’s the basis for my second “demand,” which is for ecologists to embrace the possibility of using new and emerging science to help envision new scales and configurations of urban nature that we haven’t ever seen before.

So, if planners are willing to embrace uncertainty and negative results, and ecologists are willing to put science to the challenge of envisioning and testing bold new configurations of nature, can we make a joint effort work? What do you think?

about the writer

Gil Penha-Lopes

Gil is a Portuguese transformative action-researcher on integral sustainability and nature-based design. He is a father, a PhD program lecturer and co-founder of ECOLISE (http://www.ecolise.eu/) a European platform of Community-led initiatives towards a Sustainable Europe.

Gil Penha-Lopes

Urban territories as thriving Natural ecosystems

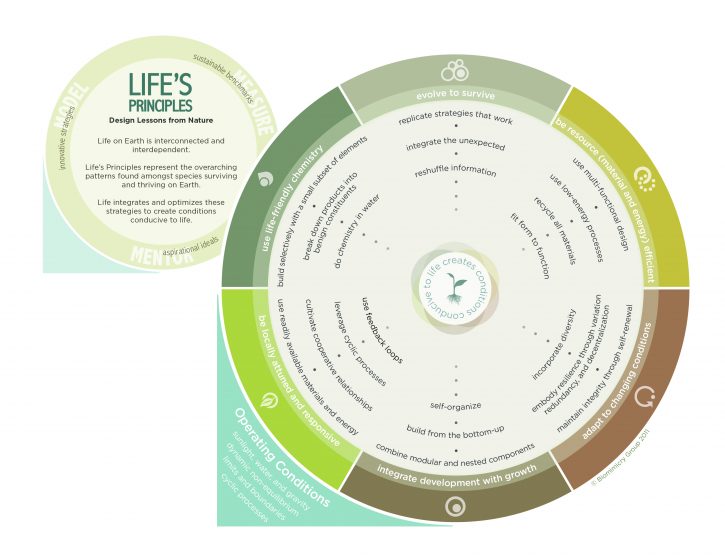

As a biologist who has worked in applied ecology and now trying to bring nature-based design into local communities and territories, my perspective and line of inquiry for how it could be done is to ask: How would Nature do it? We humans are a part of Nature, so what we do is also natural. It is my belief that if we design cities using the thriving strategies developed by Nature over more than 3.8 billion years we would save time and resources and enjoy a much-improved urban landscape and environment.

Biomimicry 3.8 is an institution that takes into consideration Nature’s six key life principles representing the general patterns that species and ecosystems use to survive and thrive on Earth.

- Evolve to survive,

- be resource (material and energy) efficient,

- adapt to changing conditions,

- integrate development with growth,

- be locally attuned and responsive, and

- use life-friendly chemistry.

I consider “integrating development with growth” to be an obvious principle that we could bring into cities. Having a good understanding of how social and ecological systems work at the city-level, and a shared vision of the cities full potential, would allow us to integrate development of the city with its growth. Some necessary elements would be support for self-organization (building capacity and empowering parishes and neighborhoods), building from the bottom-up (allows us to have urban cells, urban tissues, urban organs and the full body system working in harmony), combine modular and nested components (allowing the city to understand what is needed for each smaller unit of the territory, how these modular units complement each other. For example, having some parishes more involved in food production and others involved in research and innovation in the energy sector).

Being “locally attuned and responsive” demands cities favor the use of local resources for building material, store and use rainwater, promote the efficient use of local energy sources, build capacity among local citizens to provide the local services needed. Making good use of cyclic natural and socio-economic processes is another way to be attuned and responsive. For example, there are several public buildings that have some resources available outside normal working hours or even during holiday seasons. Gyms of public schools, for example, could be used by local groups to gather and organize their events or meetings.

I strongly believe that if cities want to thrive in the future it is fundamental to integrate in their genes and memes people that are able to complement the expertise in the urban planning department and that bring more organic, fluid and natural examples to provide inspiring metaphors for the city sustainable development.

David – that is heartening that some real on the ground impacts were made. Seemed like there were some good ingredients for the policy, and as you pointed out, long term could be in question depending on local opinion and economic pressures. I agree, if public opinion is swayed about the importance of these green areas, they may elect the appropriate officials in the future and pressure for continuance of such strategy. Bravo!

Replying to Mark

As you will realise the Greater London Plan was adopted as the strategic plan for the capital in 2004. The influence of the Biodiversity Strategy was very considerable. Some areas which were previously zoned for economic development were included in the list of Metropolitan Sites for Nature Conservation. One of the most notable was Rainham Marshes, an extensive area (over 400 hectares) of grazing marsh alongside the Thames which is now run as a major wetland nature reserve by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. I well remember the day when the Mayor of London decided that Rainham Marshes would be protected for nature conservation. I had to tell the Economic Development Team. They were aghast at the decision as it undermined the prospects for economic growth in the East End of London. In November 2002 the Mayor produced a definitive list with maps and citations describing all the Sites of Metropolitan Importance for Nature Conservation. In the London Plan published in February 2004 Policy 3D.12 states that, “The Mayor will identify Sites of Metropolitan Importance (SMIs), which, in addition to internationally and nationally designated sites, includes land of strategic importance for nature conservation and biodiversity across London. Boroughs should give strong protection to these sites in their Unitary Development Plans (UDPs). ” The London Plan thus determines the strategic framework for Nature Conservation across London. It goes on to say that, “Boroughs ( the local planning authorities) should use the procedures adopted by the Mayor in his Biodiversity Strategy to identify sites of Borough or Local Importance for nature conservation and should accord them a level of protection commensurate with their borough or local significance.”

A further element of the Biodiversity Strategy (2002) was the identification of Areas of Deficiency in Access to Nature. These were defined as areas lacking access, within one kilometre, to a high quality wildlife site (of at least borough level importance). This was adopted as a revision of the statutory London Plan in 2008. It includes advice to the London Boroughs on ways of alleviating such deficiency, such as improving ecological quality of sites, creating entirely new habitats in parts of London where there is a dearth of high quality habitats, or by improved access to sites. Some large areas of deficiency have already been substantially reduced.

Despite the statutory nature of the London Plan changing pressures on the capital, especially the demand for new homes, are likely to result in loss of important local sites which are valued by local communities. At the time when the London Plan was written the Mayor was strongly supportive of policies that protected biodiversity. We probably had the best set of statutory policies of any major city. But with growth in London’s population at current levels it seems unlikely that all sites of importance can be guaranteed protection in perpetuity. The rules can always be changed by new circumstances.

However, there have been recent indications that a popular movement to recognise London as a National Park City, could have a profound effect. Places protected by the London Plan may in fact be protected more effectively by the strength of public opinion. It is expected that the National Park City will be announced next year.

David – good to hear about the London strategy. I have been involved with several biodiversity city strategies. Most just sit on the books and do not have any real impact in terms of something happening on the ground. You stated, “A total of over 1500 sites are recognised, of which 136 are Metropolitan sites.” So does this mean there has been a new zoning that protects these areas into perpetuity? Has there been any more examples of something happening? For example, private developers had to change their practices, county and city departments actually changing their management practices, etc. Cheers

Reply to Amy Chomowicz’s question “Are there plans out there that have an ecological framework as part of their foundation?”

London has such a plan. The legislation setting up the Greater London Authority in 2000 specified that the new directly elected Mayor was required to produce a series of strategies that would together provide the basis for an overall London Plan. These were Economic Development, Transport, Waste management, Air Quality, Ambient noise, and Biodiversity. Two more strategies were added by the Mayor, one on energy and climate change and the second on culture. The legislation stated that all the Mayor’s strategies were to be compatible with each other. It also required that the Mayor’s Strategies and their implementation should have regard to sustainable development in the UK.

The biodiversity strategy, published in 2002, provided the framework for protecting a large number of sites of nature conservation value in the capital. These sites are of three kinds. Those of London-wide strategic significance are called Sites of Metropolitan Importance for Nature Conservation. Other sites are of significance within individual London Boroughs and a third category of local sites are important at the neighborhood level. A total of over 1500 sites are recognised, of which 136 are Metropolitan sites. The sites represent almost 20% of the area of Greater London. Protection of sites as described in the Biodiversity Strategy formed the basis for the biodiversity section of the overall London Plan published in 2004.

You can find a summary of this process in “Connecting with Nature in a capital city: The London Biodiversity Strategy” by David Goode In: The Urban Imperative Ed. Ted Trzyna, IUCN 2005.

In parallel with biodiversity the air quality and energy strategies provided ecological frameworks that formed the basis of the London Plan.

Ragene – you stated “In 2014, the Housing and Land Use Regulatory Board (HLURB) issued the guidelines for land use in the Philippines, integrating ecology in the planning process for cities and municipalities. .” Has anything resulted on the ground as a result of this integration? Cheers

Reply to Mark Hostetler: The Portland Plan doesn’t have an ecological framework, it has an equity framework which has been highly effective at bringing equity issues to the fore and focusing city efforts on implementing programs equitably. I’m proposing that we need an ecological framework that will infuse ecological issues, concerns, data, etc into urban plans. The ecological framework would be part of the foundation of any urban plan, and instead of just a stand-alone chapter about ecology, ecological issues would be addressed in all aspects of the plan including housing, transportation, human health, etc.

Are there plans out there that have an ecological framework as part of their foundation?

Amy Chomowicz – has any part of the ecological framework of the Portland Plan actually has been implemented “on the ground?” Just curious

Yes, cities and counties have different regulatory departments. The engineers are not rewarded for thinking outside the box. It is all about avoiding lawsuit . . . especially in the U.S. Any suggestions from practitioners that can help governments to try out new designs?

One of the barriers to integrating ecology and planning has been the historic separation of functions within municipal governments. Planners often focus on site planning, development review, and long-range planning. Public works often handles many of the ‘environmental’ tasks. Urban foresters are all over the org chart, if they have one at all. And some environmental functions are handled by state and federal agency staff. In a county plan we did a while back we proposed a Department of Green and Gray Infrastructure that would house all of the ecological and planning functions under one roof. Difficult to implement but seemingly a worthy aspiration.

I think the challenge of actually making ecology play a role in urban planning is the challenge of coordination between the different sectors and agencies to implement the various ways we know we can do that. Government agencies often work at cross-purposes. Furthermore the patchwork of regulatory bodies is an example of the mismatch between ecological and institutional boundaries and scales.

I think “ecology” is in planning, but primarily on paper (lots of urban biodiversity strategies) and what is lacking is implementation. Let’s hear from each of the writers in the comment section! Cheers Mark

In addition, at times scientists are quite certain that a particular solution will not work as intended, but if those conclusions are contrary to deeply held assumptions and values, the message is not heard. For example there’s good evidence that most green space projects will not appreciably mitigate air pollution, and may exacerbate respiratory health problems if not carefully designed. That contrasts with old assumptions (going back at least to the 19th.century) of greenspace as “the lungs of the city.” So what do we do in that situation? In addition to talking about risk, I think we need to develop a common language and process for talking about the role of values, which, of course, can’t and shouldn’t be ignored. Scientists in particular have no vocabulary for values and prefer to pretend they don’t exist! That’s also a potentially large barrier.

There seems to be a consensus in the group that ecology *ought* to be part of urban planning. So, why *isn’t* it? Alternatives…

— It’s a false trope? (ecology really is embedded in planning)

— Planners don’t think ecology ought be be there? (for what reason?)

— Ecologists don’t get involved? (why?

I agree. Much resources are invested to reduce uncertainty by generating data and information. This is of course important for decision making but excessive focus on uncertainty reduction may also cause paralysis and a lack of innovative-risk-taking thinking. As suggested by Mark and Diane, I think it´s important to take a step back, take risks and look at the big picture when planning green urban areas. In this way, planners and ecologist may work together to boost the relevance of urban green areas and position them beyond the local scale in the urban decision making agenda.