By viewing Muir Woods and other urban forests as “museums for trees,” we create the possibility of reconciliatory healing through sharing multiple narratives of place.

These visitors largely believe they are coming to a beautiful, living example of a thriving and timeless forest, protected forever by benevolent figures from the United States’ early conservation history.

After a year working as an informal educator for the National Park Service at Muir Woods, I prefer to liken it to a “museum for trees”: a stunning forest functioning and, in some vital ways, flourishing within its urban context—but not without modern human impacts that alter its character from the coast redwood forests of yore.

Like most cultural institutions, Muir Woods as a park has a complex, difficult history that—if we remember it and share it—increases the forest’s usefulness as a model for exploring contemporary questions that apply to fragmented natural areas in urban contexts worldwide. Who is nature for? How should we expect nature to look? What is beauty, and who deserves access to it? Why does a forest matter, no matter where you live?

What makes Muir Woods a museum for trees?

The first time I walked into Muir Woods as a weekend hiker, I recall snapping a photo on my phone and sending it to my father and my brother with an accompanying text: “There are real places on Earth that actually look like this.”

It’s not a dissimilar sensory experience to the one I felt on first entering the halls of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York with a high school class, or my first solo journey to The American Museum of Natural History. In many (though not all) cultures, these institutions inspire a sense of reverence, and many social signals affirm the importance and fragility of the contents they enshrine: here, guarded around the clock and displayed beneath thoughtfully-calibrated lighting, is Art. Here, behind glass and accompanied by an explanatory placard, is Science.

Here, staffed by people in familiar uniforms and Smokey-the-Bear hats, peopled with other visitors (mostly) adhering to the trail and wearing brand-name hiking attire, is the Forest. It is rare, it is visually arresting, and although we destroyed the vast majority of it, some very smart men from the past have protected the important bits of it, so that you can see it and use it as your Instagram background, and perhaps learn about the ecosystem services you experience by virtue of its persistence today (I’ll counter this particular narrative later on).

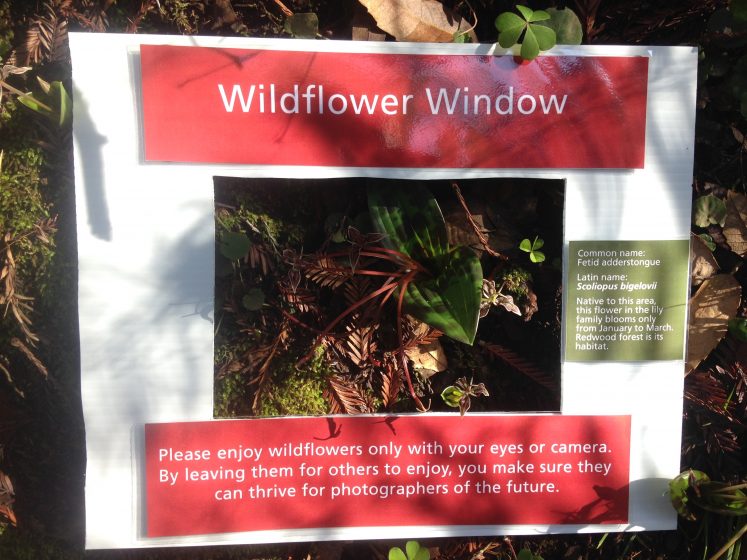

As in other kinds of museums, at Muir Woods and in the surrounding public lands, visitor participation is typically restricted to certain forms—hiking on trails, viewing wildlife from safe distances, camping in designated locations. Generally speaking, visitors to Muir Woods are discouraged from touching plants in the forest out of concern for the possibility that they will unwittingly reach their hands into a patch of poison oak or stinging nettles. Visitors may look at the Art, or the Science, or the Forest, but not experience it in a tactile way unless the exhibit explicitly calls on them to do so.

In a museum for trees such as Muir Woods, we install distance between ourselves and the Forest. In the United States’ public land paradigm, we have devised rules and signs to protect the land from trampling, littering, and destruction of habitat, among other offenses (though these are notoriously disregarded, sometimes to the mortal danger of visitors). We may argue that regulating participation in this way is the necessary legacy of humans’ disconnection from how land works, which, in turn, is inexorably followed by an inability to respect that land.

I believe that “museums for trees” such as Muir Woods innately contain the possibility of beneficial outcomes for forests and people. They also have limiting outcomes that, if we aren’t thoughtful, can preclude us from seeing novel ways of being in relationship with the land.

Yet, certain outcomes emerge when we treat so-called natural spaces in this way—as places where visitors are often vaguely menacing, destructive consumers as opposed to potential co-creators.

Below, I’ll consider some of these outcomes, and how we can use the conceptual example of Muir Woods as a museum for trees to realize more beneficial outcomes, more often, and for more people in our urban public lands.

What we build and what we lose from a museum for trees

When we create “museums for trees” by designating urban forests or other sorts of natural features as parks with amenities, programs, services, and rules, we can increase accessibility to nature for diverse audiences that may have no connection or negative associations with such places—but we don’t always do so successfully.

For example, Muir Woods offers a length of trail accessible to wheelchair users and assistive listening devices for those who are hearing impaired. Folks who arrive directly from San Francisco can safely walk through the redwoods in flip-flops on the raised boardwalk if that is what makes them feel comfortable in the forest.

Providing such infrastructure is integral to making public land equally accessible to variously-abled people with a diversity of backgrounds and experiences. It is one way we can follow through on our capability to increase accessibility to nature. However, it is also low-hanging fruit in the world of increasing access to civic spaces.

While lack of a safely graded trail can be an initial deterrent, there are many other, subtler ways that natural spaces, similar to exhibits in art and natural history museums, have been made hostile to different communities. That hostility is often unspoken, or manifests through omissions in the way we tell the story of a site.

To illustrate, return to the photograph above, the one with the wayside titled “Saving Muir Woods.” Over a timeline that charts the history of the forest beginning in the early 1800s, the text of this exhibit tells readers that when William Kent and his wife, Elizabeth Thacher Kent, owners of Muir Woods in the early 1900s, were threatened with eminent domain (a local water utility wanted to log the old-growth grove, dam the creek running along the valley floor, and turn the forest into a reservoir for public water), William Kent was outraged. He used his stature as a well-to-do Progressive to gain an audience with President Teddy Roosevelt via Gifford Pinchot, the first head of the U.S. Forest Service.

Kent was able to convince Roosevelt of the value of the forest for leisure and recreation, and shortly thereafter, Roosevelt used the power of executive order—as granted to the president by Congress in the Antiquities Act of 1906—to designate the redwood grove as a National Monument. Kent insisted that instead of naming the forest in honor of his donation of the land, Roosevelt should name it after John Muir, the beloved naturalist and writer who founded the Sierra Club.

This sounds like a happy, if simplified, story of Good, Genteel Nature Lovers triumphing over Bad, Greedy Loggers, right?

Just as I viscerally learned when I invited a friend to The American Museum of Natural History in New York and he responded, “The natural history museum makes me uncomfortable—the way it puts black and brown people behind glass like rhinos,” a little context substantially shifts the connotation of the “Saving Muir Woods” story in key ways.

Kent, the educated son of a merchant, moved to the Muir Woods area as a child; unlike the vast majority of people moving west during the Gold Rush Era (but similarly to most of the men responsible for crafting the tenets of the early American conservation movement), he associated nature with enjoyment and as an expression of moral values rather than as a source of livelihood.

When he went on to campaign for public office later in his life, Kent repeatedly ran on a fervent platform of Asian immigrant exclusion. In a 1920 speech in San Francisco, he said, “We who happen to be of English descent are proud and happy in the fact that the country from which we came was not overrun by successions of peoples yellow and black and indiscriminate in their breeding.”

In working to protect the redwood forest from logging, Kent was adhering to values that other “Progressive” white supremacists had cultivated, relating the ancient stature of the Coast Redwood species with preserving the purity of the white race. From Charles Goethe, who linked conservation of tracts of redwoods with his advocacy of eugenics, to Madison Grant, a zoologist and redwood protector whose 1916 book, The Passing of the Great Race, or The Racial Basis of European History, was lauded both by Adolf Hitler and Teddy Roosevelt, these men feared the loss or muddling of lineages, including that of the redwoods, that they considered superior.

What does this history lesson have to do with the opportunities presented by the forest as museum?

When we tell a more complete story of Muir Woods, it is suddenly ensnarled with the very foundations of identity-based controversies that are embroiling our national politics in 2018. The site becomes highly relevant to intersectional justice for all kinds of communities, urban and otherwise, that have historically been exploited or excluded in relation to nature and public land.

Perhaps even more so than in traditional monuments to art, history, or culture, our public lands offer in situ opportunities for reconciliatory healing when we interpret them fully, via a multitude of perspectives.

That we struggle to share these stories in the containers—the forests, city streets, prairies, oceans, urban rivers, statues, and parks—where they are most vivid is what Nina Simon, executive director of the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History, might call a problem of relevance.

In her book, The Art of Relevance, Simon draws an elegant, elongated metaphor that equates a museum to a room. The vibrant content and community a museum can offer (if they are doing strong, effective programming) lives inside the room; those as yet unfamiliar with the value of that content are situated outside the room. The key to the door that separates the Inside and the Outside is Relevance.

People who feel comfortable inside the room are already acquainted with the value of its contents—in the case of Muir Woods, insiders might include avid hikers, local families, park volunteers, or park staff. Insiders are sometimes resistant to change—and when the content of the room is altered to be more inclusive, some of those insiders may object. But by sharing specific, challenging histories such as the one I’ve related above, we can invoke the deep relevance of the forest—or any other natural urban space—to those audiences on the outside, and increase the number of people who see their stake in nature without much altering the parameters we’ve put in place to guide them.

By viewing Muir Woods and other urban forests as “museums for trees,” we can apply Simon’s metaphor to these natural spaces. In doing so, a primary benefit of the analogy emerges: the possibility of creating reconciliatory healing through sharing multiple narratives of place.

I’m proud to note that Muir Woods has embarked on this work, as has the entire Interpretation and Education division within the National Park Service. Today, many parks are trying to take an “audience-centered” approach in their programming and, based on recognition of an exclusive past, seek to share untold histories with their audiences. As an entry-level interpretive ranger, I was encouraged to devise programs in this framework and to discuss difficult knowledge—from institutional racism to indigenous issues to climate change—wherever they applied to Muir Woods. Of course, there is plenty more of this healing work to do.

I’ve just made an argument in favor of thinking about a forest park as a museum for trees—but perhaps the earliest pop cultural reference to the idea, Joni Mitchell’s 1969 song Big Yellow Taxi, is more critical. The lyric is a familiar one:

“They took all the trees

Put ’em in a tree museum

And they charged the people

A dollar and a half just to see ’em”

There’s something distasteful to thinking of Muir Woods as a museum rather than as a forest—when I discussed the idea with visitors, they rejected it out of hand, expressing reluctance to think of the forest’s survival as being inextricably interwoven with humans’ activities.

Unfortunately, this reluctance is seated in the same premise that the men of the early conservation movement held about nature: a mythic idea that forests and other natural spaces without humans are perfect, rising and plateauing in a static, pinnacle state. So thought French Romanticist François-René de Chateaubriand, who wrote, “Forests precede civilizations; deserts follow them.” Likewise, Kent located value in Muir Woods because of his perception of it as “untouched.” In a 1907 letter to Gifford Pinchot, he wrote of the forest:

“It is an object of great scientific value in its wealth of primal tree life and the rare and delicate flowers and ferns found only in an untouched redwood forest.”

The Muir Woods of Kent’s time was hardly untouched; prior to their being forced from their homeland and enslaved in the Spanish Mission system, the Coast Miwok people had influenced the forest through landscape-scale burning for thousands of years, shaping the appearance of the forest that Kent and other descendants of Western Civilization chose to see as “primeval.”

The reality of the forest as we find it today is also one of profound human influence, though that influence is largely damaging: the health of the Coast Redwoods’ understory community, the climate processes that determine its biological characteristics, and the persistence of its natural history strategy are threatened by the massive changes people have made within its range over the last 250 years, from rapid deforestation to industrial urbanization, to climate change.

By isolating an old-growth forest such as Muir Woods, we may cut off the stand from the community context that has typified the forest since the last Ice Age—for 10,000 years, more than 2 million acres of connected old-growth Coast Redwood forest blanketed the coast of California; post-logging, the area covered by old-growth stands is approximately 120,000 acres, a full 97 percent reduction from just a few human generations ago.

This loss sets the stage for a wrenching sense of grief that we might also associate with the redwood forest as museum—a place where we put on display trees that, through human actions, have been prevented from performing their evolved function in perpetuity.

Joan Naviyuk Kane, an indigenous poet who writes about her Iñupiaq heritage, illustrates the tragedy of this idea best. In an interview, she spoke about seeing a drum her grandfather had made in a museum’s collections:

“It got me really thinking. Is it still a drum if it is never to be used again and remains only in a museum’s collection? Are they objects or are they poems now?”

Reckoning with the past to create a novel future: lessons from redwoods

If we choose to pay attention, the relationship of indigenous Californians to the landscape offers a lesson for visioning urban forests, such as Muir Woods, both as forests and as the kinds of museums we want: participatory community centers that connect us to each other while instilling us with deep knowledge of the landscape, rather than as elite institutions that serve certain narratives over others.

For thousands of years, California Indians (like indigenous people across the Western Hemisphere prior to European contact) actively managed landscapes at a scale that was virtually impossible for Europeans to conceive at the time. Vast evidence for this management contradicts the premise discussed above—that in order to preserve its truest character, tracts of “wilderness” must be left utterly alone, as free as possible from human influence.

In her book Tending the Wild, M. Kat Anderson writes, “Interestingly, contemporary Indians often use the word wilderness as a negative label for land that has not been taken care of by humans for a long time…When intimate interaction ceases, the continuity of knowledge, passed down through generations, is broken, and the land becomes ‘wilderness.’”

By thinking of Muir Woods as a museum for trees, we create an opportunity to hold a duality: that we need more people, not fewer, to interact and care actively for the landscape where it appears in their daily lives—whether in their local urban national park, community garden, wetland, or tidal marsh—and that, by providing extensive guidance (that sometimes takes the form of rules and limitations) in what activities are appropriate, we offer them a portal into the Inside of the urban nature room—where their stake in protecting the resilience of urban nature becomes self-evident, and they become the new ambassadors inviting Outsiders, in.

Laura Booth

San Francisco

Leave a Reply