This article describes a new approach to graduate studies, that works at the dynamic intersection of environmental issues and social justice. The Master of Arts in Education with Urban Environmental Education program out of Antioch University in Seattle, has attracted a very diverse student body, who illuminate daily the challenges, struggles, and strategies unique to people of color striving to enter the environmental field. If cities are to be places where all thrive, unraveling inequity, exclusion, and discrimination is paramount. Diverse voices and experiences will build resilient cities.

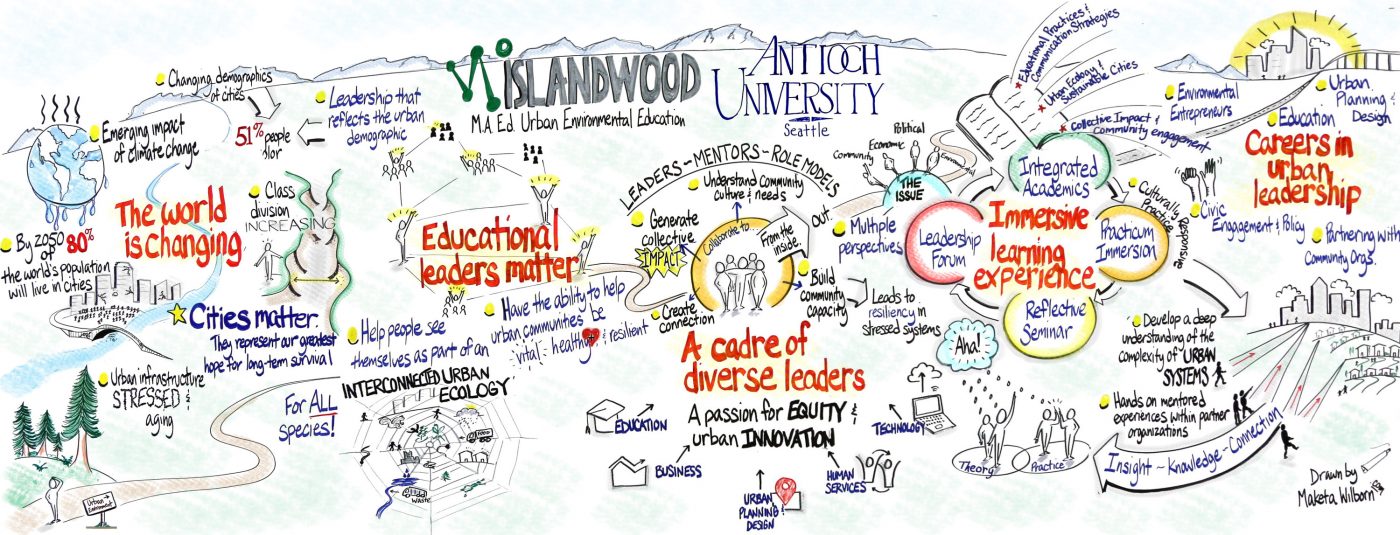

I spent 2014 doing the market research for a new Master’s degree in Environmental Education for IslandWood, an environmental non-profit on Bainbridge Island. As part of the process, we convened several groups in Seattle and New York City that included community leaders, activists, and organizers in the design effort. The participants were asked one question: “What is the work that needs to be done in urban areas?” Maketa, a graphic facilitator, and I collected their thoughts and translated them into the graphic representation below. The shape of the program is new and refreshing. Traditional environmental education was turned on its head. Launching a program that would prepare a new and diverse cadre of environmental leaders emerged as the unanimous goal.

- The world is changing: More live in cities, and they are increasingly diverse culturally and racially.

- Cities matter as they represent the greatest hope for long term planetary survival, sustainability, and resilience.

- Education has the power to transform the way that people live in cities.

- Urban communities will only thrive if they are engaged collectively from the inside out or the ground up.

- Urban solutions depend upon the preparation of a diverse cadre of environmental leaders.

The three strands described below shape the pedagogy, practice, and outcomes of the Urban Environmental Education program.

Use the City as a Learning Platform. Place-based and experiential approaches to urban environmental education are aimed at connecting people to the biosphere, to place, to intersecting natural and human-made systems, to change and impacts, to cultural perspectives, and to identifying power, voice, and agency as urban stewards.

“Empty lots are more than just ‘holes’ in the urban façade. They represent the character of a resilient ecosystem, a possibility for vibrant green space in the making. As educators, we help make these possibilities visible and highlight their importance to community strength, health, and resilience.”

-Tiffany Adams, Alum of UEE Cohort 2

Focus on the complex socio-ecological dynamic of the urban environment, which includes the ecological, social, political, and economic forces that shape it. Urban environments are ecosystems in which human and ecological health is heavily interdependent.

“Classes are carried out in the city, on the streets, observing and investigating through the perspectives of those who live there. I’m learning to design educational strategies that prepare community members to recognize and act on the impacts of climate change, to identify impacts on environmental health, and employ sustainable practices that lead to the creation of equitable and just solutions.”

-James King !!!, Alum of UEE Cohort 3

Develop cultural fluency among environmental educators. Urban areas are dense and increasingly diverse. We seek to engage all people as urban stewards, and its practitioners must represent the diversity of racial, cultural, and ethnic perspectives that live and work in cities. The full story of the urban landscape as a complex socio-ecological place means grappling first-hand with issues of inclusion, equity, and justice.

“Providing intentional voice to environmental justice means that I have personal work to do…studying my culpability, my entanglement. It means integrating issues of power, access, privilege, and fairness into thinking about how I educate others.”

-Danielle Nicholas, Alum of UEE Cohort 3

This new approach to Urban Environmental Education intentionally integrates issues of environmental and social justice into the narrative of every academic course and practical experience. Students actively apply the dynamics of equity, privilege, and power as they wrestle with environmental issues. Students insist that they are ‘expanding’ the dominant paradigm of environmental education to include multiple racial, cultural, and ethnic perspectives and experiences.

“The dominant environmental narrative in the US is primarily constructed and informed by white, Western European or Euro-American voices. The black experience of nature always bumped up against social, economic, and historical processes that serve to remind them that their map of the world, while fluid, demands a particularly fine-tuned compass that allowed them to navigate a landscape that was not always hospitable. In the future, environmental programs must address the connections linking race, identity, representation, history, and the environment to awaken from our historical amnesia and create a more inclusive, expansive environmental movement devoid of denial and rich in possibility.”

-Carolyn Finney, Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors

We found that most urban communities are exhausted by universities who use them for their own ends. One of the most powerful parts of the program is the 40-week course in Participatory Action Research culminating in a Legacy Project. Students are hired by community organizations in a research capacity with the intention that their research serve the community directly. The research is defined through the ‘eyes’ and interests of the people who live there. The integrity of the research is guided by Paulo Freire‘s approach to community engagement and education. We embed our students in urban communities, to listen closely and without judgment to the everyday experiences, struggles, and solutions percolating among the people who live there.

The UEE program integrates a different set of elements to “nature interpretation”, which includes high-density residential and commercial infrastructure, transformed waterways, waste streams and paved surfaces, air and water quality, and access to healthy food, shelter, and green space. Understanding urban complexity and the interdependence of the natural and the built environment is key to our work. Cities are becoming places of “new nature”, a shifting perspective that is not always green. Understanding the nature of a city requires an intentional shift in environmental perception and educational practice. It requires a new conceptual and pedagogical frame for environmental education that influences the way theory and practice are conceived and delivered.

“There is a serious disconnect between the changing demographics in our country and the lack of diverse leadership and staffing at organizations that protect our health and the environment.”

-Mustafa Ali, Senior Vice President of Climate, Environmental Justice and Community Revitalization with the Hip Hop Caucus

As a learning group, we peel back the layers of the city by walking them, talking with residents and listening to those who live there. Urban ecology is a deep study of the ways that people and nature intersect, influence, and support each other. The students remain our best teachers. The majority are people of color from the guts of cities around the country.

Rasheena is from Chicago, Tiffany is from New York City, James is from Atlanta, Niesha is from Los Angeles, yet they find common ground in their experiences as people of color and as environmental leaders. Every day they, not so gently, open our minds to see a different reality that has actually been there all along. This new environmental lens is one that most of the students live every day, one that transforms the traditional white wilderness model of environmental education to include a parallel awareness of environmental racism, inequity, and exclusion. As one student exclaimed, “I’ve been here all along, you just haven’t and don’t see me.”

In our classes, the realities of race, equity, and environment are a constant theme, sparking hard conversations about power and privilege, barriers and misconceptions, assumptions and implicit bias. Students of color, for the most part, are for the first time in their lives the participating majority in classes. When invited to bring their ideas, feelings, perceptions, and experiences forward, they feel safe and supported. What we hear from them deserves a voice in the larger arena of the environmental field and yet, finding a foothold in environmental organizations continues to be difficult despite the multiple initiatives to create diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) mission statements.

The traditional white wilderness model bit the dust early on. Communing with pristine nature is replaced with finding the assets in neighborhoods where most people live including city parks and green spaces. The overwhelming message is that not all people have the means, the power or the voice to ensure the environmental vitality of a place. Social justice plays a big role in determining how people live and thrive in cities.

“As educators, long-term results rely on building trust among constituents, learners, and community members. First, we build relationships…authentic and real relationships. Relationships are key to the longevity of any environmental solutions. We need to step outside of our personal assumptions, our biases, our stereotypes and listen to the stories from inside a community. The real experiences of everyday people shine a light on the environmental issues they face. Embedded in those stories are the keys to building stewards of urban places”.

-Jess Wallach, UEE alum Cohort 1

This new program design is cohort based. We live and learn by working through the layers of experience, multiple perspectives, disparate values, and visions of how cities might work better for everyone. The first three cohorts have drawn 60 percent diversity, bringing African American, Hispanic, Asian, and White educators together for 15 months of study and practice. The definition of environmental education has expanded. The traditional environmental education values and goals are consistently questioned and reformulated. Our work is to better understand the nature of cities (rather than nature in the city) from the perspectives of those who live deep in their communities.

“I continued on for years feeling like an outsider in search of environmentalism as a Black woman who grew up partly in inner city Chicago. That was until I realized that I was on the wrong journey. I realized that I hadn’t shown up late to the party, but I had unknowingly stumbled into and was asking to be let into the wrong party. The environmentalism of John Muir and Aldo Leopold was indeed not my environmentalism—not my Chicago community’s environmentalism and not my family’s environmentalism. To be a Black environmentalist means reconciliation with the land and reconstructing the perceptions of nature. It means embracing the toiling of my grandmother in her Chicago backyard urban garden, stepping beyond the nature documentary dreams of my grandfather, and embracing that we too have always been and are environmentalists who may not always fit ‘the mold’.”

-Rasheena Fountain, Climate Conscious Collab April 21, 2018, UEE Alum Cohort 2

“Leadership will never be measured by what one person is able to accomplish as a result of his or her talents and abilities alone. It can’t be. The word itself implies the existence and participation of motivating and moving with others.”

-CJ Goulding, UEE Alum Cohort 1

On an unrecognized and nearly invisible plane, there exists a parallel universe of environmentalists who add important perspectives, approaches, and styles of leadership to a notoriously white profession. It’s time to see the change, make the change and realize the potential of multicultural inclusiveness in building resilient and just cities.

The students want their stories to be accepted and as well known as Muir and Leopold. Following their lead, traditional approaches to EE are “unpacked” and reworked into a radical intersection of environmental leadership and social justice. Their thinking is fresh and drives educational practice to dance on a necessary edge. These newly recognized voices are rising and challenging us to consider new ways of thinking about old ways of being.

“I hope I am working to add to the plurality of perspectives and stories of relationships with the land. It’s a bridge that I and other environmentalists of color are working hard to build. For this reason, no matter how dissonant it feels, I will keep uttering the phrase ‘I am a Black environmentalist’, even if my dreams may be deferred.”

-Rasheena Fountain, Climate Conscious Collab, April 21, 2018, UEE Alum Cohort 2

Cindy Thomashow

Seattle & Dublin

Add a Comment

Join our conversation