We are working on a photographic series exploring the connection between the reclamation of ponds and marshes and their promotion for recreational activity. The Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland was created by visionary landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead whose designs “stage nature” by directing the gaze of the viewer and engaging contemplation of our place in the living world. The introduction of our miniature tent into this setting considers the compromise between anthropogenic interests and non-human nature.

Covered in dried algae and hitchhiking seed burrs, we pack our gear into the car. It is getting late, we want to get to Eden’s Landing before sunset.

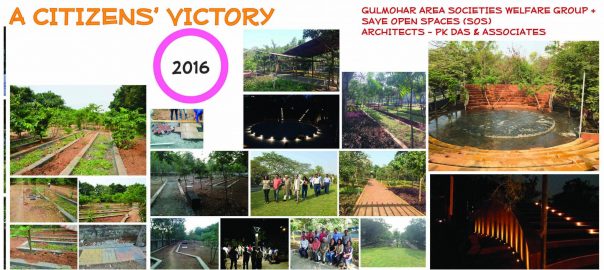

Eden’s Landing emergency relief tent celebrates a Bay Area environmental victory; the restoration of the artificially made salt ponds flanking the southern shores of the bay back to its original wetlands eco system. As far as changing the physical structure of Southern San Francisco Bay, no industry, not even waste disposal, has had as great an impact on the environment. In the past, more of the south bay had been diked and ponded for salt than not. Eden’s Landing emergency relief tent, as an intervention in this landscape, becomes a celebratory marker for this important transition of the land and water back to their original states.

The return of natural tidal flows along the South San Francisco bay constitutes one of the largest wetland restoration projects in history, turning stagnant industrial ponds into vital sustainable ecologies. Salt has been harvested from the San Francisco Bay since the mid-19th century in a patchwork of salt evaporation ponds. Cargill, an agricultural chemical company based in Minneapolis is the contemporary entity overseeing this process. Cargill works with Morton salt which processes the harvest.

Things changed in 2003 when a large swath of coastline was returned to the public as a wildlife preserve. Since that time, the wetlands are recovering and now support migratory birds, brine shrimp, fish, and people! The restoration areas are now popular recreation sites for hiking, kayaking and photography.

Video: Electrical towers stretching over the restored salt marsh at the Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge. Human infrastructure shares the environment with endangered species such as the California gray fox and the western snowy plover.

The next day we crossed through Yosemite arriving at Mono Lake in time to witness the setting sun glowing hot magenta, hurling shimmering embers across the surface of the water before disappearing behind the Sierra Nevada mountains. Tufa formations along the lake banks and extending into the shallows reinforced a sense of an otherworldly landscape. Tufas are calcium carbonate columns, the result of freshwater mineral springs beneath the surface reacting with the alkaline water of the lake. Their visibility is evidence of an incomplete recovery; they should be underwater. And the dramatic color, amplified as light scattered over atmospheric particulates from the wildfires in nearby Mariposa, was a consequence of drought and human negligence. Sometimes beauty is deceptively complicated.

Located 350 miles north of Los Angeles in the Eastern Sierras, the tributaries that feed Mono Lake were diverted for city use for over seven decades dropping the lake level 40 feet until successive litigations finally halted withdrawals. Mono Lake is part of an Endorheic basin, a system with no outlet save evaporation. Normally the lake is already three times saltier than the ocean. But evaporation without adequate replenishment precipitated a near ecological collapse in one of North America’s oldest lakes. Conditions have improved, but the vicissitudes of climate change are still a threat.

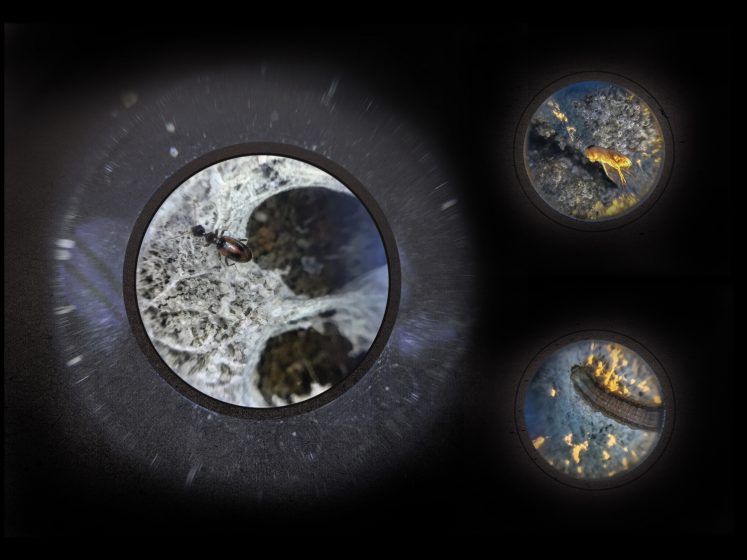

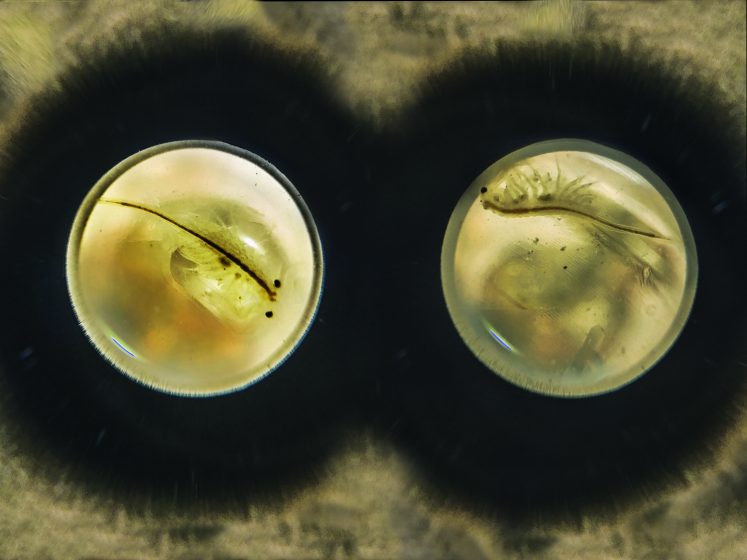

The next day was hot. Carrying awkwardly shaped, heavy, three-foot steel armature tent sculptures a mile through scrub brush to photograph under the dessert sun is a sweaty business, so we went for a swim. Swimming in Mono Lake is encouraged. The water is warm with a distinctive slippery feel. Pinkish clouds in the blue water are formed by trillions of tiny Artemia monica, a species of brine shrimp unique to Mono Lake. Small brown/black flies rested along the shore. The lake biome is contingent on brine shrimp and alkali flies; the shrimp and flies eat algae and the birds eat the shrimp and flies; as long as there is an inflow of water and stable pH levels the system works. Simple.

Tourists from all over the world passed us by as we worked. A few paused to watch with puzzled looks. A group of visitors from Germany asked: Are you shooting an advertisement? We thought, yes, in a way, and replied: We are making images that encourage recreational use of the lake to build support for conservation. One of the men smiled appreciatively: Oh yes, we were just reading about this.

Beauty and rarity alone are never enough. Humans need a reason, a benefit.

Reclamation + Recreation = Water.

Robin Lasser and Marguerite Perret

Oakland and Topeka

about the writer

Marguerite Perret

Marguerite Perret conducts collaborative, arts-based research that scrutinizes the narratives inherent at the interstices of art, science, healthcare and personal experience.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation