At Suparichit, there is a sense that although this site could be easily dismissed from a distance as a vacant wasteland, it is perhaps the closest thing this community has to a central park—one being intensely utilized every day by a multi-species range of local stakeholders. How can we help it evolve?

Scrolling through the polycentric expanse from above, one can easily trace the broad strokes of a megacity still caught up in the rapid process of becoming ever more “Mega.” Look closely and you might barely manage to trace the serpentine shadows cast by double-stacked urban flyovers (UFO’s). Or the zigzag of dusty urban streets, forming a dense jumble of discontinuities and dead-ends. Look closer still, and you might make out the bright clusters of tarpaulin tent communities, which crystallize like blue ice at the fringes of burgeoning shopping malls, high rise apartment blocks, and expansive corporate tech parks.

Continuing this process of low resolution aerial wandering, you might eventually find yourself hovering in the approximate location of 13.058199 latitude, and 77.617179 longitude, at which point you would encounter an unmistakable landscape anomaly.

Within this oddly dappled territory at the southern edge of Rachenahalli lake, Google curiously identifies a landmark—The “Dreamz Suparichit Appartment”, yet no such development (as of yet) actually exists. Could this be a digital specter of a developer’s speculation? A promise of what’s to come?

One can only assume that this site dreams of becoming one of the many towering residential complexes which are commonplace throughout the city—offering luxurious three bedroom flats, promising escape from the ills of the seething urban core, fresh air and unobstructed lakeside views. The perfect setting for an up and coming family of urban professionals.

For now, what actually exists within this space of roughly 10 acres is a captivating expanse of piles. These heaps of earth could be loosely defined as the detritus of development—dug up from nearby construction sites and illicitly dumped here in an ongoing process that is slowly subsuming the former agricultural landscape below them. It’s a refugee camp of sorts, for displaced dirt. They aggregate, creep forward, and spread out to form a vast territory with many strange and beautiful juxtapositions—vertical strata of soil once suspended in invisible layers beneath the earth’s crust have been recast as a rich horizontal mosaic which ranges from Bangalore’s distinctive terracotta-colored topsoil, to piles of sand and rock which appear as bleached as the dunes of the Sahara.

These curious features of the landscape appear both intentional and naive. They arise not as product, but as byproduct. This expansive landscape produced at the “Suparichit” site reflects a range of frenzied and unfolding processes that remain barely hidden from view and comprehension: the centrifugal forces of real estate speculation, the mechanical maneuvering of deep excavation, and the machinations of India’s informal labor market, all converging to deposit the detritus of development to the fringes of the city in thousands of clandestine after-hours truckloads.

A park by any other name

How do we even begin—as ecologists, urbanists, landscape practitioners—to make sense of such sites? Should they be written off and maligned as just another “Tragedy of the Commons”, a wasteland, an unfolding ecological disaster? Or do they represent an inevitable process of transition to a new condition, a disturbed pixel in an ever changing mosaic of urbanization? Or might it be something else entirely? Seen from the elevated, godlike perspectives of GIS or Google Earth, it would be easy to categorize such sites as merely one of the “Remnant”, “Ruderal”, or “Managed” landscape conditions which are typically used as reference points in the analysis and classification of urban land-cover and land-use.

Yet to encounter this place from ground level—as an embedded human subject—tells a much more nuanced and interesting story.

Intrigued as we were by the complexities implied by remote sensing, we first paid a visit to this site “in the flesh” on a cloudy day in the spring of 2017. Our aim wasn’t to judge, blame, or diagnose, but to observe. Rather than producing a clear or singular reading, we soon realized its capacity to contain a symphony of opposite and parallel identities. Wasteland. Wetland. Place. Non-place. Each of these monikers is equally valid, and simultaneous.

The stories told in the spaces on top of, and between the piles are as numerous as the piles themselves: Of traditional agricultural communities contemplating the return of the monsoons, of contemporary developers crunching their returns on investment, of mothers carrying the day’s laundry back and forth. The sounds of human laughter mix with the stern thunder of cattle calls, the constant metallic clamour of nearby construction, the guttural cries of migratory cormorants, and the howling of feral urban dogs, all mixing together, yet never quite in harmony.

These identities are reflected in the in the daily life of the territory, where cows can still be seen grazing and swimming in the margins of the wetlands, overseen by local Cowboys (“Hasu Kayuva”) who now use the elevated promontory of the piles to keep prospect on their animals. Seeds dispersed by wind and birds and foot traffic are giving rise to spontaneous trees shrubs and creepers, emerging in the rich substrates of discarded soil and rubble. To be on the lookout for cobras is a common warning.

In the trenches of Suparichit, one impression began to emerge: a sense that although this site could be easily dismissed as a vacant wasteland from above, it is perhaps the closest thing this community has to a central park. Though its formation is entirely informal and undesigned, it is a vibrant urban commons nonetheless—one that is being intensely utilized every day by a multi-species range of local stakeholders.

Landscape intervention as catalyzing gesture

As urban ecologists and creative practitioners, we are often trying to create a critical feedback loop between studying urban ecosystems, and shaping them. Many of the previous interventions staged under the auspices of The Commonstudio have been unsanctioned yet intentional—social-ecological gestures that catalyze new landscape perceptions and processes. These tactical interventions are all about intervening in small ways, but creating ripples that extend, unfold, and evolve over time.

Yet the question of intention in this case proved to be a slippery one. What can we introduce here that could never happen otherwise? How might we catalyze new processes that point not to the past, but to the present and future? What would it look like to imagine new modes of participation and ecological engagement that invite and nudge rather than prescribe and control? How do we reconcile our own status as outsiders? And perhaps most importantly in this case, when enormous budgets and timeframes necessary for formal modes of remediation or placemaking are simply unavailable, what can you do with 20 dollars (1200 Rupees) and some human sweat in the early hours of a Sunday morning?

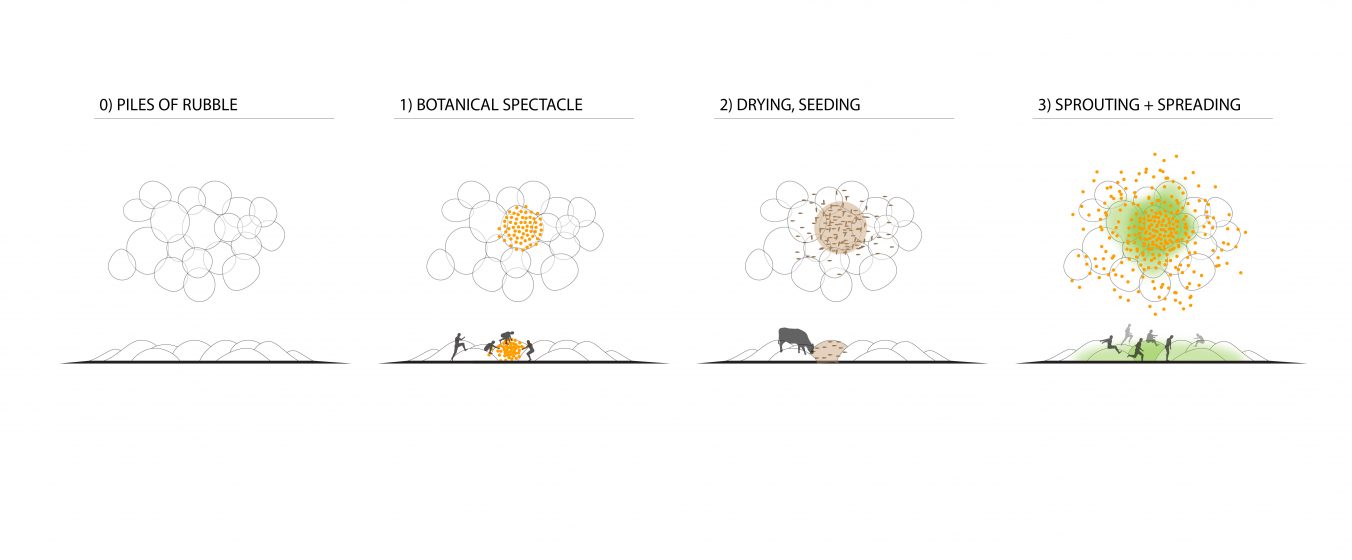

Pile Study #1 offers a radically simple, singular gesture aimed at inviting new narratives of value for this liminal place, which is largely referred to as a wasteland by local residents. The tactic of introducing charismatic micro-flora into highly disturbed or maligned urban ecosystems has been explored elsewhere in our work and in the work of many others before us. Whereas seed-based interventions often offer a delayed promise of profusion, we were seeking something with more immediate gratification.

When we arrived on-site on a still morning in August of 2017, the sun was just starting to rise, and the smell of damp dirt and hot algae filled the air. After an early morning trip to Bangalore’s famously frantic KR Flower Market for supplies, and a ragged rickshaw ride to the periphery with 25 kilos of blooms in tow, we were ready to roll. Targeting a single pile along a common path of pedestrian travel, we began methodically inserting a blanket of Marigold flower heads to a state of stark relief from its surroundings. This had originally been intended to appear anonymously, like a mysterious form of environmental “Banksyism”. Yet as it unfolded, we were surprised and delighted to see this initial gesture instead created a magnetic visual spectacle which invited immediate engagement with local communities, who were compelled to actively participate in its construction.

As the morning grew warmer and brighter, we noticed a group of onlookers in the distance. They slowly crept closer, tentative but curious. Within 20 minutes we were joined by the nine young men—local laborers from the surrounding informal encampment. They laughed and commented to each other in Hindi and Kannada, and seemed perplexed by the fact that we didn’t speak a word of either. Yet they stayed, digging small pits in the piles and placing flowers until the bags were empty, snapping photos of the outcome.

Perhaps this act of consecration speaks to the powerful role that the Marigold (Tagetes erecta) holds in Indian cultures. The flower is used widely in rituals marking thresholds, attracting auspicious energy, and paying homage to the sacred aspects of daily life. With its hearty green vertical vegetation, vibrant orange flowers, and prolific re-seeding habit as an annual plant, the Marigolds’ aesthetic and ecological properties also provide a means of visually mapping the afterlife of the intervention in both space and time as the site continues to evolve. When we returned to the site two months later in November, each flowerhead had indeed acted as a seedbank, sprouting life into a new generation with the help of the recent monsoon rains.

The Pile Study is part of an ongoing body of social-ecological experimentation that we hope can contribute to the widening discourse on marginalized urban ecosystems—not just as places worthy of looking at through new eyes, but worth caring for in new ways. Implied in a growing body of action and research are exciting new horizons for creative and civic engagement that reframe these territories as assets rather than liabilities in the fight for more just, more vibrant, and more resilient cities.

Those within the urban landscape practice are particularly well-positioned to conceive of new modes of co-evolutionary bargaining which respect the existing ecologies and informal cultural heritage produced within these marginalized landscapes. Under new paradigms of understanding and collective action, highly disturbed territories regarded as functionally and ecologically useless today may ultimately be recognized and utilized as key contributors to the health of the urban ecosystem in the near future. It’s time we develop more coherent ways to work with and alongside these conditions, however messy they may be.

Daniel Phillips

Bangalore

Leave a Reply