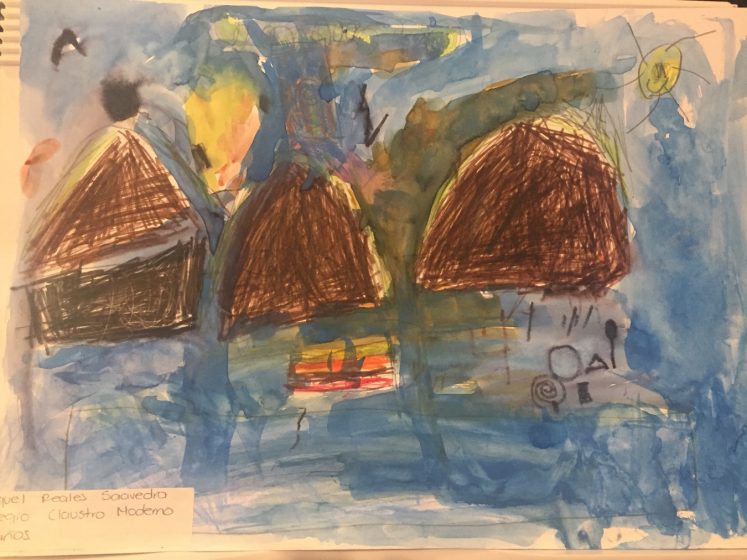

“What I like about this landscape is that it’s not painted….I can move around into it and feel it. I think about all the things I can find there. But, after I leave this picture, something always changes, and I do too.” —Gabriela Villate, 7 years old.

People see a face in the landscape, one which is directly related to their daily lives, to their well-being and to their sense of belonging to a place. This is the idea of the landscape as a “face, or geographical form of space” (Fernandez-Rodriguez, 2007).

What happens when we “freeze” the landscape on pieces of paper? To find the answer, for the past eight years our foundation, Fundación Cerros de Bogotá, has been inviting children from Bogota and the surrounding region to paper our walls with their landscape drawings. (Bogotá is a humid tropical city located at 8,700 feet above sea level, on a highland plateau in the eastern range of the Andes.)

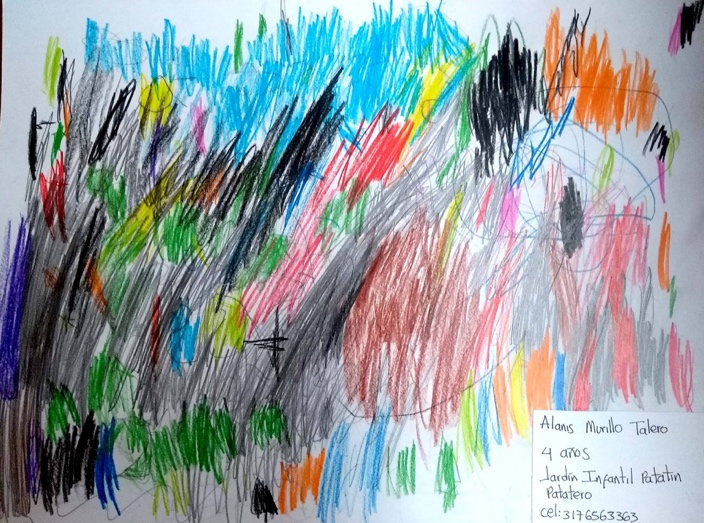

Last year alone, children from diverse backgrounds sent us more than 2,000 drawings of Bogotá’s mountains and their surroundings. Some of the drawings are included in this essay, but you can see many of them in the video below.

Why should children’s drawings be taken into account when making decisions about the city’s future?

Children’s landscape drawings often include members of their immediate circle: teachers, parents, friends, classmates; which means that a child’s representation of the landscape can go beyond being just a simple portrait of a piece a land. It can also include “the formal representation of emotional relationships among individuals and societies…shaped by social, economic, environmental and cultural factors” (European Landscape Convention, 2000).

It is “any part of a territory perceived by the local population, the character of which is the outcome of actions and interactions produced by natural and/or human factors” (European Landscape Convention, 2000).

Over the course of many years, Fundación Cerros de Bogotá has advocated for a comprehensive plan by which to guide the development of the city’s mountain border. This plan is based upon community participation, and emphasizes biodiversity as the most important structural component in a socio-ecological pact that links neighboring communities throughout the mountainous corridor. The concept of such a socio-ecological system encompasses a comprehensive perspective of the ecosystem, including the cultural component. Therefore, when the social value of an ecosystem is measured, humankind’s perspective and participation in it must be included.

However, to date, our efforts have only slightly influenced public decision-making, due to the fact that the mountains’ cultural and environmental importance barely registers among local politicians. Such is the case, even though a November, 2013 Colombian Council of State ruling decreed “that unoccupied areas surrounding building sites are to be given priority use as ecological public spaces to compensate the residents of Bogotá for any ecological damage that may have occurred on said building sites, thereby guaranteeing the public right to recreation.”

Because city governance is highly complex and involves a wide variety of actors, each of whom has specific political interests, and because local public policies are generally executed at a sluggish pace, the city’s mountain border, with its enormous potential to improve residents’ daily lives, remains widely overlooked.

So, in pondering all of these children’s drawings and listening to their stories about their interests, we began to realize that these children would be our greatest allies in bringing about the changes for the city we have been dreaming about.

Because Bogotá’s eastern mountain range is so vital to the city’s environmental, social, and cultural development, the Colombian Council of State, in a 2013 ruling, ordered a number of public institutions to carry out programs that would compensate the city’s inhabitants for the years of ecological damage that has been done to the city’s mountainous border.

In the frame of a proposal made by this author: “The Eastern Mountain Ecological Corridor”, also known as the “City Border Pact” (see Note below), recognizes that the city’s incomparable eastern mountain border must be protected through civic agreements that will ensure biophysical restoration and the public’s right of use and recreation within the designated Green Belt.

This Pact involves three major strategies: the social, the biophysical and the spatial, all of which are based upon regenerative planning and social inclusion. The Pact’s overall aim is to restore the area’s biodiversity while at the same time ensuring that the local community participates in territorial appropriation for the benefit of the entire region. This project was created in an effort to halt the ecological degradation and fragmentation of the city’s eastern mountain range; to this end, it has established guidelines, objectives, regulations and designs for the development of the mountain socio-ecological corridor.

We began to understand that effective change could only be brought about by forging a long-term pact with the actors and neighbors who live in and around the city´s mountain range; and that this pact that would also have to actively include the area´s children and young people both in and out of their schools.

Approximately 74 private and public schools and 13 university campuses are located along the 36-mile Bogota mountain border. Some of these educational facilities can occupy up to 150 acres of private property. On the basis of this data, it was clear that the more than 11,600 mountain school students, as well as other students from elsewhere in the city, would have to play a major role in protecting this ecological corridor.

The future of Bogota and its mountains depends upon local children becoming eco-citizens and agents of change

In order to provide greater scope to the annual exhibit of children’s drawings and narratives that fill our Foundation’s headquarters every year, we decided to set up a Bogota Mountain Schools Network. This strategy includes Bogota schools in the management of the city’s mountain range. Students are encouraged to hone their knowledge of ecological sustainability through the study of local geography and environmental resource management.

We can talk about eco-representatives: children as eco-civic citizens and managers of change in the future of the landscape and biodiversity at the region of Bogotá.

Why have we called upon students to become eco-representatives?

Children’s landscape drawings provide an unassuming means for them to express themselves. During the past eight years, as we have collected thousands of such drawings, local politicians have produced few, if any, tangible programs to protect Bogota’s Mountain Reserve. Therefore, we founded a transversal education task force, The Bogotá Mountain Schools Network, to focus on promoting eco-education as the basis for long-term nature conservation. This task force now includes, in addition to the Fundación Cerros de Bogotá, Opepa, the Gimnasio Femenino (a private campus on the mountain border), and other partners: the Bogota Botanical Garden and the Instituto Humboldt.

The individuals who guide these institutions, with their tireless commitment in time and energy, have made it possible for us to reach a number of our goals.

The Bogotá Mountain Schools Network gives private and public school children the chance to participate in important environmental initiatives that will affect their surroundings in the future.

Our task force has invited a number of children from diverse backgrounds to attend our meetings where they are designated as “important urban naturalists”.

Meeting of Important Urban Naturalists sponsored by the Bogotá Mountain Schools Network and held at the facilities of the Instituto Humboldt.

“My father told me that when he was a student, the school had to take everybody to visit the Sumapaz Paramo, or some other place high up in the nearby mountains”—the Sumapaz Paramo, or high mountain meadow lands, is a rural area within Bogota’s city limits; at 44,000 acres, it is the largest paramo in the world—”but, nowadays, kids don’t know very much about local geography. These drawings show how students who walk to school at the foot of the mountains see them, as well as how students who live far away are only able to see the mountains’ profile at the edge of the city.”

Getting children involved in activities and decision-making within their own surroundings contributes to their tapestry of relationships and nurtures better citizens capable of transforming the cities they live in. The jointly-sponsored process we have described recognizes children’s perceptivity of their surroundings as well as their relationships with neighbors; it aims to transform consumer habits by making them more eco-friendly; and, in the long-term, it aims to influence public policy, education and child-rearing. Moving beyond being mere representatives of an ideal or of being critics of the current situation to being active participants among residents in micro-territories will hopefully serve to unite every Bogotá neighborhood in creating a more equitable urban environment, where nature’s spirit will reside in every home.

The landscape of the future is child’s play.

Diana Wiesner

Bogotá

Translated by Steven William Bayless

References:

Carmen Fernandez-Rodriguez. 2007. Landscape Protection, IN A Study of Comparative Spanish Law. Madrid, Editorial Marcial Pons y Ediciones Jurídicas y Sociales, p. 58.

European Landscape Convention. 2000. Article 1, Sec. from Florence, Italy, October 20.

Fernandez-Rodriguez,Carmen. 2007. Landscape Protection, from A Study of Comparative Spanish Law. Madrid, Editorial Marcial Pons y Ediciones Jurídicas y Sociales, p. 58.

Zuluaga, Diana Carolina. 2015. The Right to the Landscape in Colombia, Universidad Externado de Colombia, Bogotá.

Note: “The Eastern Mountain Ecological Corridor”, also known as the City Border Pact, recognizes that the city’s incomparable eastern mountain border must be protected through civic agreements that will ensure biophysical restoration and the public’s right of use and recreation within the designated Green Belt. This Pact involves three major strategies: the social, the biophysical and the spatial, all of which are based upon regenerative planning and social inclusion. The Pact’s overall aim is to restore the area’s biodiversity while at the same time ensuring that the local community participates in territorial appropriation for the benefit of the entire region. This project was created in an effort to halt the ecological degradation and fragmentation of the city’s eastern mountain range; to this end, it has established guidelines, objectives, regulations and designs for the development of the Mountain Recreational and Ecological Corridor.

Valoramos mucho sus comentarios!

Con gran entusiasmo seguimos adelante teniendo la red entre los niños, para que conozcan y valoren su territorio, para que se conozcan y se reconozcan como actores en esa geografía tan generosa que tenemos.

Muchas gracias !

Que bonita forma de crear conciencia ambiental desde las edades mas tempranas, es así como se logra el respecto y el reconocimiento al valor del paisaje, la identidad territorial y la apropiación para beneficio colectivo. Si entendemos que como seres también somos naturaleza, no los dueños de ella, podremos planificar y diseñar teniéndola en cuenta, conociéndola, estudiándola, analizándola, comprendiéndola y protejiéndola. Sinceras Felicitaciones a la Fundación Cerros Orientales y a todos los que participan y apoyan de una u otra forma esta linda, admirable y relevante labor.

Que lindo projeto Diana! Parabéns!

I love the use of emotional and relational landscape within the article . I totally agree as well that children must be heard in order to have a sustainable vision. Please do share more the intention of the mountain’s pact in order to have a shared vision and, above all, commitment. Thanks for all your work!!!

Es muy pertinente el artículo ! Los niños son el futuro para consolidar el gran pacto por los Cerros. La Fundación Cerros de Bogotá desde un trabajo mancomunado con otras organizaciones e instituciones ha sido de vital importancia para la recuperación, protección y restauración de la montaña como un sujeto de derechos.. Por este motivo, es muy valioso que sigan empoderando a los niños de los colegios de Bogotà, para que sigan transformando e imaginado el paisaje desde sus propios entornos, sentimientos y emociones de su propia cotidianidad. Excelente labor al equipo de la Fundación.

Me gusta mucho que la fundación incentive el cuidado del medio ambiente en los niños. Es muy importante que tomen consciencia de lo importantes que son los cerros y los ecosistemas en general. Me gusta que a tan temprana edad se les inculquen valores de cuidado y respeto por el medio ambiente, ya que con ello tendremos una generación que dimensione lo importante que es el cuidar la naturaleza.

Que gran labor desempeña la fundacion cerros al articular a los niños en el cuidado ambiental. Generar esta conciencia en el pequeño a largo plazo generara una sociedad mas comprometida para cuidar los cerros, borrando los errores que se cometerieron nuestros mayores

Remarkable work that is done in the Fundación Cerros de Bogotá. Sowing that seed in all children, is a community building strategy with a truly broad and sustainable vision.

Thanks for your efforts.

Gracias por los comentarios, el ejercicio debe afinarse cada año . Precisar el origen del niño, el lugar donde vive y plasmar algo de narrativa o bien, hacer grabaciones de su narrativa.

Seguimos desarrollando esta herramienta y trabajo para llegarle a la institución.

A través de la mirada de los niños se puede encontrar tanto el potencial del paisaje presente, como los deseos del paisaje futuro, se hacen evidentes percepciones que alimentan su sentido de entorno y medio ambiente, la apuesta de la Fundación Cerros de Bogotá al trabajar con los niños, incentiva hacer presente la noción de paisaje y forma con cariño un concepto perdido entre los adultos.

Ver como ven los otros, y si esos otros son los niños, hace posible entender la lectura del espacio físico de nuestra ciudad. Por un lado nos muestran sus dibujos la calidad del color que la industria ofrece en materiales para la expresión gráfica, me refiero a los tintes de color que aparecen en las temperas, crayolas o lápices que se usan en las escuelas de nuestra ciudad. Y por otro lado y quizás el que me permite leer con cuidado la percepción del espacio fisico es la capacidad de los niños para dibujar diferencias entre el suelo donde están ubicados al realizar su obra y las distancias a los cerros. Ver cómo representan en sus obras gráficas los detalles de la vegetación, los colores que mezclan para hacer las formas de los árboles, el color del aire y las edificaciones urbanas.

Este ejercicio de la Fundación Cerros de Bogota debe ser parte del estudio de nuestra manera de apreciar el entorno. Vale la pena conservar dibujos de cada convocatoria para analizar cómo cambian estos dos aspectos antes mencionados. Larga vida a este ejercicio que fomenta la pertenencia a un lugar, el reconocimiento de nuestros. Error y la valoración de la expresión infantil de nuestros afectos por la naturaleza.

Espectacular!!!! Que labor tan bonita la que hace la Fundación!! Los felicito! Definitivamente la clave está en educar a nuestros niños siendo conscientes de la importancia de preservar el medio ambiente y las montañas que son vitales para nuestra supervivencia en Bogotá! Completamente de acuerdo con formar eco ciudadanos que conozcan su entorno y lo protejan! Bravo Diana y todo su equipo!!!!