On 14 June 2018, Isabelle Anguelovski participated in the panel Designing, Planning and Paying for Resilience at Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research, where she and other leading experts discussed flood mitigation strategies such as low impact design, green infrastructure and urban-scale greenspace preservation, and how they interact with a community’s broader planning efforts. These are Isabelle’s insights from the panel.

It seems to me that one of the most controversial green resilience planning initiatives post-Harvey has to do with the buyout program. Buyout programs are sponsored by the Flood Control District from Harris County, where Houston is located, and financed by federal grants as well as local funds. They consist in buying out houses and other types of properties to address potential flood damages. The land in which those properties is located is then often turned into green infrastructure and.or green spaces. From the meetings and discussions I was part of, residents in African-American and lower-income communities showed concerns about this approach because of displacement and relocation issues and their fear of not being able to afford anything in a nearby community with the money they’d receive, even if the buyout program would pay them a fair price for their house. Those fears also stem from long-term trauma related to housing segregation and discrimination. Lastly, residents also seemed concerned about the loss of community ties as a result of this displacement.

How do these programs affect residents, more specifically?

A lot of these fears seem to be manifested in neighborhoods like Independence Heights and Kashmere Gardens, the former being the first incorporated city in Texas in 1915 and still mostly African American. Residents claim that elevating homes would be “resilient enough” and cost less (50% less than a buyout), but this “preservation” approach is not a commonly used strategy in Houston, where a more common approach has been about tearing properties down, replacing them, and/or greening. Also, many lower-income flood victims don’t have the funds to rebuild or elevate their homes and FEMA won’t insure them, which means that many of them leave their neighborhood. So, there are new forms of insecurization in those neighborhoods linked directly or indirectly to Harvey, infrastructure planning, and green resilience.

What is the role of local real estate developers in this process?

When residents walk away and the land is not part of the buyout program, developers come in quickly and flip the lots. This can be a goldmine for them. Many even seem to be encouraging residents to sell and/or leave their property to be able to access land considered as prime location for their investment strategy.

Neighborhoods like Independence Heights will also likely have a substantial proportion of its edges being taken over by the expansion of highway I45, along which there will also be new townhouse developments. Residents perceive this as a move to remake their neighborhood for upper income residents whose new homes will be the gate of entry to the community and who will have direct access to new highway ramps and be very close to the business district and midtown. All of this process means that the historic black commercial corridor—and the jobs that go with it—will be torn down, which is of course creating deep concerns of displacement for residents.

Displacement is also social and cultural because developers and other investors, like Whole Foods, contemplated changing the name of the neighborhood to “Garden Oaks” as they announced new businesses or projects, and thereby erasing its historic African-American identity and significance. As everything in Texas happens without having to deal with governments, developers can run their business without governments, and activists don’t often have the power to respond to developers. This was basically the bottom line of people’s analysis. And there is no political system responding to community organizing, which makes organizing a really daunting task. Another complexity in Houston is that there is also a lack of a Master Plan or Resilience Plan in which community activists could take part, but are not.

Despite the relative absence of historic community organizing, are there any grassroots movements contesting displacement and gentrification?

Activists in Houston neighborhoods repeatedly pointed out at the lack of community organizing capacity in Houston beyond what researcher Dr. Kyle Shelton calls “infrastructure citizenship”, or when residents organize for or against roads, transit, and other mobility-driven projects. Houston was not highly active during the civil rights movement, unions were crushed very early on, and churches never seem to have played the organizing role they played in other places such as Alabama or Georgia. One activist I met said: “People don’t organize residents at the base of power.” Many members of Black congregations have moved out, so there is a cultural and spatial disconnection there that prevents present-day organizing through churches. Churches also don’t seem to be used to organizing in their congregation.

There is, however, a fantastic group called EEDC working in the historically black Third Ward neighborhood of Houston, where people have engaged in community planning since 1985. They work on building community wealth through partnerships with anchor institutions, mobilize residents towards political and community action, strengthen community ownership and housing choice, revitalize Emancipation Avenue as a dynamic and safe business corridor, support preservation efforts, and mobilize faith for spiritual health. Among their fights has been the preservation of and community access to Emancipation Park, the first public park in Texas, which just reopened in 2017 after a $38M high-end renovation. Despite incorporating design features from the neighborhood architecture, EEDC and its constituency have been particularly concerned about its green gentrification potential due to new nearby development interest. They were also critical of a $10M budget dedicated to new bike trails, feeling that this money could have been used for much more immediate needs such as housing and health.

What particular tools do you see communities using to resist displacement in Houston?

There’s been some success with the community land trust (CLT) model. At first, residents pushed back against MIT Colab’s proposal to put up a CLT. Many residents were afraid that a CLT would mean redevelopment of lots into townhouses, which have been criticized for spurring gentrification—attracting suburban residents back to the center in search of more dense neighborhoods and housing—and that Black residents would not own the pieces of land they had fought for decades and centuries ago.

Activists talked a lot about “free slaves” having fought to buy land, about those that had not been able to participate in the Great Migration and had had to stay in areas like the Third Ward where, later on, Black residents had been forced to move after being redlined from other neighborhoods. Now, a few generations later, Black residents are afraid of seeing their history being taken away again. For them, CLTs don’t always deal with history very well. Eventually, however, the model of CLT for the Third Ward was supported by residents as a way to resist gentrification, and is embraced by EEDC. And now the city of Houston has adopted a city-wide community-land trust model. This is an important evolution to follow.

What other strategies are being used in the Third Ward to address gentrification threats?

There seem to be two see two camps in the neighborhood: the arts and preservation groups that fight for affordable housing and the presentation of existing housing stocks, and the redevelopment groups that, among others, push for parks as an amenity for residents and newcomers. As part of the anti-gentrification movement, EEDC has also worked on dynamizing community-owned and driven economic development through main street businesses, small businesses, and creating workers’ cooperatives around needs in the local economy such as construction. Supported by Project Row House, a community platform empowering residents and enriching community through engagement, art, and direct action, EEDC folks are mapping and identifying who lives where and is doing what, connecting people to jobs, to each other, and to the political apparatus. Part of their focus is lobbying the city to literally pay and compensate residents to attend planning meetings so that residents can have a meaningful contribution to planning processes in their neighborhood. They try to address unfair burdens on residents and avoid reinforcing inequalities. For them, robust community engagement has to factor in inequality, and thus pay low-income residents to attend planning meetings.

A key challenge for EEDC is how to secure lots and key properties adjacent to newly redeveloped parks like Emancipation Park so that they don’t get rebuilt into townhouses. There are lots next to the park that were previously “affordable housing” (private affordable housing) and that are now for sale. Here, activists that fail to support greening initiatives are faced with the possibility of losing their seat at the table, and thus their chance at addressing these issues.

You often warn of green gentrification. Could you give us some other examples of how this and other types of green inequalities are happening in Houston?

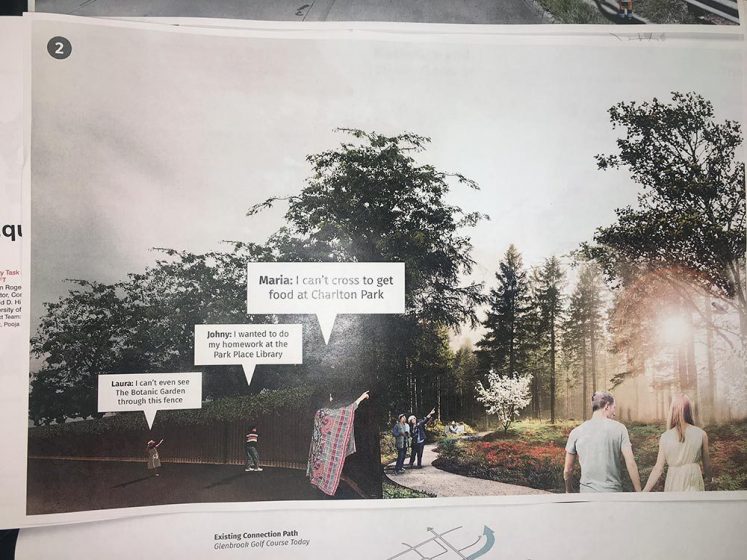

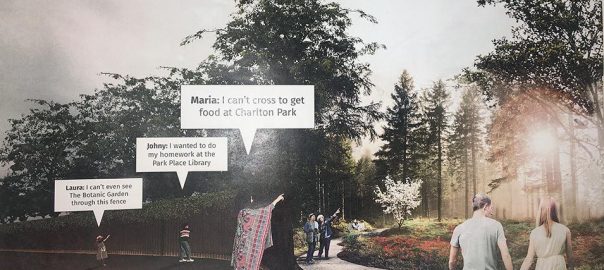

Park Place is a minority neighborhood where the city is building a highly controversial Botanic Garden to replace a public golf course which was also used as a connection through the community. It will be a fenced-off, fee-based space that obliges residents to make a detour in order to access a local school and community center. It is also destroying natural wildlife growing on the edges of the golf course. Despite the huge uproar, the private developer and city are moving ahead with it, as Prof. Susan Rogers well explains here and here.

In another instance, a municipal program called Spark Park, which aims at sharing school parks and open spaces with local residents, excludes most low-income neighborhoods in which school play and green areas remain locked up after hours. Nevertheless, the City counts them as new accessible green space for residents as a way of improving statistics on acres of green space per resident in lower-income areas of the city.

In addition, while there are several programs to revitalize Bayous (local rivers), including Bayou Greenways 2020), and open up new bike lanes and trails, some residents find that more privileged neighborhoods benefitted first. One of the trails started from center of Houston outwards. Why would you not start with more outer bayous where lower-income residents also have less access to green space?

What are the more structural issues that prevent green gentrification and other environmental inequalities from being addressed by state agencies or municipal decision-makers?

First, developers have a huge power in Houston. Many public officials seem to have their hands tied because of developers’ influence on decision-making. It’s a historic issue. Real estate development is at the core of Houston’s economic development together with the petrochemical industry. This also explains why you have entire low-income minority communities, like Manchester, sitting right next to a refinery or another contaminating plant.

Second, inclusionary zoning, or the dedication of a portion of new residential buildings or new developments towards affordable homes, is illegal in Texas. Developers are given a free ride throughout the city and development can go run rampant. However, some Texas cities are finding creative ways to go around this restriction. For example, Austin, is allowing for inclusionary zoning in “Homestead Preservation Districts”, which are seen as an important tool to fight gentrification.

Are there other ways to address displacement in Houston?

Another program that addresses displacement is the Major Activity Corridor (MAC). In areas designated as MACs, while developers have the right to densify and build housing townhomes and taller buildings, regulations on building heights are much more stringent just outside those corridors, which provides guarantees for the preservation of historic homes. It has also been fascinating to read about the development of a campaign called the “minimal lot size campaign” to prevent developers from turning lots into townhouses. Townhouses seem to have this terrible connotation of being ivory towers parachuted into low-income neighborhoods, as they are usually fenced in, have no ground floors, and where homes are placed above garages to create a sense of seclusion from the rest of the neighborhood.

Researchers in your group in Barcelona (Barcelona Laboratory for Environmental Justice and Sustainability) often advocate for comprehensive neighborhood-driven planning. Is this taking place in Houston?

There is an interesting municipal program called Complete Communities to write up community plans and pilot projects for lower income neighborhoods and integrate health improvements, affordable fresh food access, open and green space, and overall neighborhood revitalization into local development efforts. There are five Complete Communities through the city. The program is derived from recommendations from the Mayor’s Equity Task Force. However much of the funding for it seems to be shifting towards resilience planning. Bringing the two together could work well if you consider all those issues as part of long-term community resilience without reducing resilience to climate disaster preparation, but I am not sure if this is what local officials have in mind.

Funded by the State of Texas, there is also a parallel program called the Opportunity Zones Program to use tax deferrals to steer capital towards more economically and socially fragile communities, some of the targeted communities being in Houston. The funds would serve to invest in business equity, housing, infrastructure. In this case, however, much attention will need to be paid to ensure inclusive redevelopment and build on existing community-driven comprehensive or small-area plans in order to avoid new displacement threats.

How can Houston learn from similar experiences in other cities?

I’ve recently started to conduct field work in Boston, where I did much of my previous research on community organizing and environmental justice in the United States. There are powerful groups and networks there, such as the Center for Cooperative Development and Solidarity (CCDS) or the solidarity economy network/initiative, which mobilize around alternative economic development models and political and economic transformation. This kind of transformation is essential so that residents and groups that have historically been left behind can also propose and build new pathways for the city and themselves. Boston also has a Greater Boston community land trust network, which is another transformative model for land control and development for and by residents, on which to further build.

Isabelle Michele Sophie Anguelovski

Barcelona

This interview originally appeared here.

natures and cities?