While adaptation plans focus specifically on climate impacts, the scope of resilience planning is often broader. This makes city resilience plans in some ways more like comprehensive or sustainability plans. Nevertheless, more cities are now opting for resilience plans instead of stand-alone adaptation plans. This begs the question: What are the implications of this shift for local climate change preparedness?

In a recent study published in the Journal of Planning Education and Research, my colleagues Sierra Woodruff, Missy Stults, Chandler Wilkins, and I examine whether resilience plans in the United States appear to be substantively different than adaptation plans. In doing so, we contribute to a broader debate about whether resilience is simply the latest buzzword or a truly more integrated and flexible approach for preparing for future challenges (Davoudi et al., 2012; Coaffee et al., 2018).

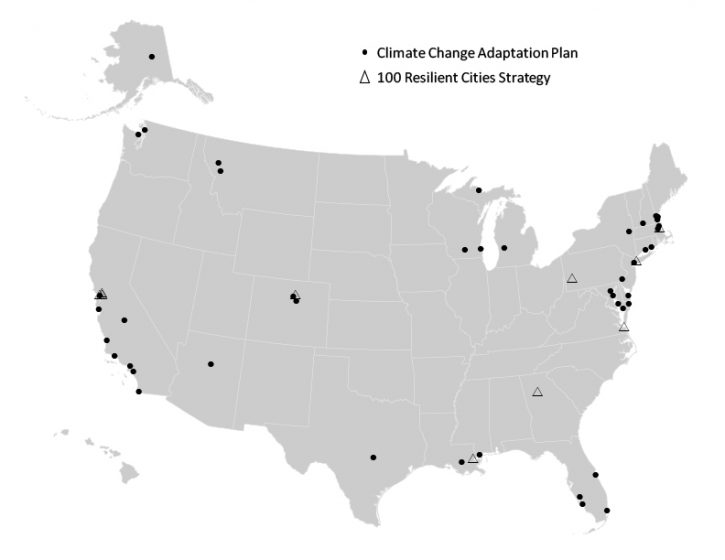

To address this question, we use established plan evaluation methods to analyze the first ten US city resilience plans released through the 100 Resilient Cities program and compare them to a sample of 44 climate change adaptation plans. (See map below). We score each of the plans based on 124 criteria that relate to seven plan quality principles: (1) goals; (2) fact base; (3) strategies; (4) public participation; (5) inter-organizational coordination; (6) implementation and monitoring; and (7) uncertainty. We supplement this quantitative plan analysis with semi-structured interviews of officials in seven of the cities that are part of the 100 Resilient Cities program.

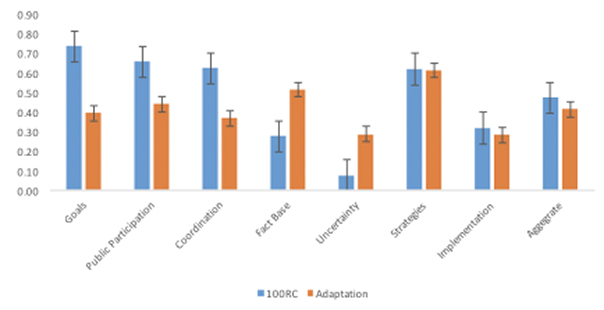

Our plan analysis shows that when the seven principle scores are combined, the average quality of the adaptation and resilience plans are similarly low (scoring less than half the possible points). This suggests that there is considerable room for cities to improve how they are planning for climate change impacts. Moreover, when we break down the average scores for resilience and adaptation plans by the seven principles (see the graph below, in Figure 2), there are some important differences.

Resilience plans do a better job of clearly articulating goals, engaging a broader set of organizations, agencies, and the public in the planning process, and acknowledging the linkages between different threats and systems. Our interviews support the idea that resilience planning encourages cities to prepare not just for climate change, but a variety of interconnected shocks and stressors. But we find that the resilience plans score worse than the adaptation plans on the Fact Base principle, meaning that fewer resilience plans include data on baseline climate conditions, future projections, or risks. It seems that there may be a tradeoff between added breadth (in terms of threats) and the depth of analysis. This supports earlier work by Lyles and colleagues (2017) that suggests that narrow-scope adaptation plans are more integrated and do a better job directing development away from hazardous areas than broader-scope ones.

The fact that resilience plans tend to score better on Public Participation and Coordination principles seems to support the idea that resilience encourages collaboration and breaks down silos, but in this study we cannot determine whether this stems from something unique about resilience planning per se or the 100 Resilient Cities program. I recently launched a research project — in collaboration with Sierra Woodruff and another researcher at Texas A&M, Bryce Hannibal — to examine this question by analyzing flood resilience planning networks in four U.S. coastal cities.

We find that adaptation plans, on the other hand, have a stronger fact base. For example, they are more specific about climate impacts and more likely to reference IPCC and other models. Adaptation plans also score significantly higher than resilience plans in how they acknowledge and address future uncertainties (e.g. through robust or no-regret strategies), although this is the lowest scoring principle for both types of plans. We found this surprising, given the focus in the literature on adaptive management and flexibility as characteristics of resilience (Meerow & Stults, 2016). There was no significant difference in the Implementation and Monitoring principle scores, but both plan types scored quite low.

We recognize that some of these results may be specific to the plans produced through the 100 Resilient Cities program and may not be generalizable to all resilience planning efforts. Cities were selected for the program because they were already doing innovative work and then they were given additional guidance and support that likely influenced how they conceptualized and planned for resilience. Other cities might not have the same level of capacity. Nevertheless, the 100 Resilient Cities initiative has been so instrumental in shaping the broader urban resilience agenda that we think it is worth examining these plans.

Our findings suggest that resilience and climate change adaptation planning have different strengths and weaknesses. Across the board, plans need to focus more on identifying robust strategies that work under a wide range of future scenarios and provide more details on how these strategies will be implemented and monitored.

Because the meaning of resilience is itself contested, we also look at how the different plans define resilience. Unsurprisingly, climate change adaptation plans generally define it more narrowly in terms of withstanding climate impacts. The resilience plans generally conceptualize resilience in broader terms, considering a wide array of shocks and stressors. Even though the 100 Resilient Cities program has its own definition of resilience, cities often modify it. For example, some cities make equity or justice an explicit part of their definition. Boston’s plan, for example, states: “Achieving citywide resilience means addressing racial equity along with the physical, environmental, and economic threats facing our city.” Other cities focus less on equity. Some plans define resilience as an outcome, others a process. These differences show that resilience is still a malleable concept.

In short, while resilience has clearly become a central feature of urban research and policy discourse, it remains a fuzzy and contested concept. As one of the first studies to systematically analyze multiple city resilience plans, I think our paper can help us begin to understand the different ways that cities interpret and apply resilience into plans and policies, and how this will help them grapple with future challenges, but we still have much to learn.

Sara Meerow

Tempe

Add a Comment

Join our conversation