While Zagreb’s circumstances and regimes changed, planners often remained, pulling the values of the previous period and linking them with values of the next period. Most of the time positive aspects remained while the undesirable ones were replaced.

Zagreb indeed has a rich and complex history. It entered the 19th century as a small town in the Austrian Empire only to become the largest city and the capital of Croatia in the mid-19th century. The change in the balance of power between Austrians and Hungarians resulted in subjugating Croatia to the Hungarian Kingdom which governed it as a colony, suppressing its social and economic development. The First World War marked the end of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire and Croatia united with other south Slavic nations in the Yugoslav kingdom where Zagreb was the second largest city and economic centre. The short fascist phase during the Second World War was followed by almost half a century-long socialist period in which Zagreb was again the economic centre of Tito’s Yugoslavia. The independent era finally began in the 1990s with Zagreb becoming a modern European metropolis. So, over the last 200 years, Zagreb lived through changes in government forms, ideologies, planning ideas and practices, and, all of this impacted how greenspace was perceived, planned, and maintained.

Zagreb: Circa 19th century

Before the 19th century, Zagreb was a small town with two separate cores: religious (Kaptol) and secular (Gradec). Both were built densely within the fortification walls for protection from Ottoman conquests. In such a compact area, there was not much space for parks, so the city’s rural surrounding provided most opportunities to enjoy nature. Where green spaces did exist in the city, they were primarily designed around religious buildings, as is the case in Kaptol, where the churches’ green spaces were almost exclusively reserved for the clergy. It wasn’t until the end of the Ottoman Empire in the 18th century when urban parks around the two settlements really started to take root (Barešić and Sirovec, 2011). Yet, it remained the case that the creators of these parks were most often the bishops of Zagreb, as they owned most of the land around the town. In the same way, today’s largest park in Zagreb—Maksimir—was created. Its initial development was influenced by the baroque landscape design ideas penetrating from central Europe. Although imagined as a regular-structured French garden, construction took many years. It was finished in the mid-19th century in the style of an English landscape garden with many romantic elements.

The golden age of urban greenspace

A new era of urban greening began when the two cores, Kaptol and Gradec, began to merge together in the city of Zagreb. At this time, Zagreb was industrialising. Railway construction accelerated population growth and economic development, and as the population moved into the city Zagreb expanded rapidly, creating new quarters and “absorbing” surrounding villages (Slukan Altić, 2012). The separation between church and state led to the civil government overpowering the clergy, and landscape design became a civil activity. Zagreb got an official architect and urban planner whose task was planning the construction of new parts of the city, which also included the greenspace. City planners in Zagreb were usually schooled in other large cities of the Austrian Empire, and design and style in these cities greatly impacted planning ideas in Croatia.

Notably, the utilitarian aesthetic of German planners, Ernst Bruch and Reinhard Baumeister—for whom beauty was almost synonymous with practical—guided aesthetic in the city of Zagreb. This can be seen in the construction of a green belt around the new city centre. Modelled on Vienna’s Ringstrasse, a chain of seven parks was designed as a visual barrier around the new city centre as well as a kind of buffer zone protecting it from air and noise pollution originating along the railway (Slukan Altić, 2012). Due to its U-shape, the park chain came to be known as the Green Horseshoe. Another change characteristic for this period was the redevelopment of many medieval graveyards around churches into parks as the civil authorities started considering them as non-aesthetic and non-hygienic (Barešić and Sirovec, 2011). As industrialisation increased the city’s income, greater investments were made to further city expansion.

Socialism and urban planning in Zagreb

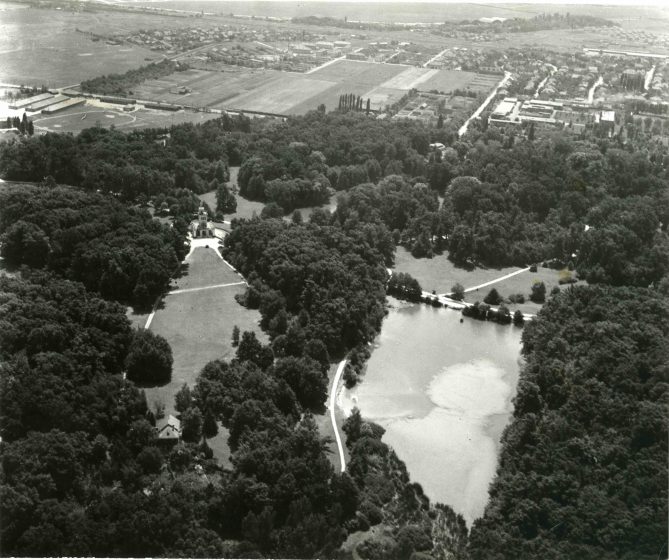

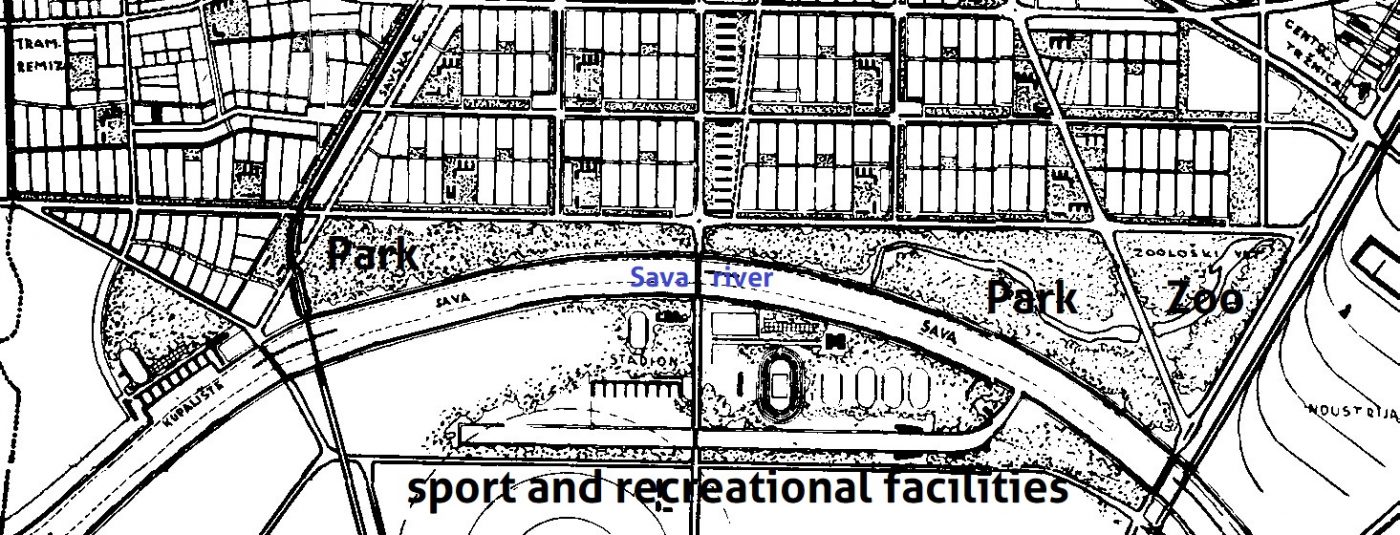

As the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed in 1918 with the end of the First World War, Croatia became a part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In united Yugoslavia, Zagreb became an economic centre. Under these conditions, the development of new working class quarters did not follow the urban plans set in place earlier but progressed uncontrollably and informally. This caused overpopulation and led to a lack of focus on preserving greenspace (Bašić, 1989). The authorities, therefore, planned a green zone with recreational facilities along the river, which the city reached in that period, but due to a lack of money, only the green lawns were realised (Matković and Obad Šćitaroci, 2012).

During the Second World War, the socialist party took over the government, and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia became the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). The change in political values and government structures was blended with the urbanistic tradition. Socialist urbanists seemed to be aware of the benefits for workers population provided by urban greenery, including the effect on physical and mental health (Kiš, 1976). The care for urban greenery was demonstrated already in the early post-war years. Since the country did not have the financial means, the new regime implemented a decree in which the citizenry was organised to repair the damage in the city caused by the war and re-build the city. In this wave of public works all the existing parks were renewed and, according to the socialist ideology, the fences around them were removed so that access to parks were open to all. The socialist regime also nationalised all the land in urban areas, with the exception of the privately owned buildings on these properties (Simmie, 1989) to ensure planning went unimpeded, and smoothly according to socialist ideological principles.

Socialism also widened participation in urban greenspace planning processes. The general public could engage in greenspace planning by proposing ideas and implementing projects together with official service workers in charge of greenspace. One of such initiatives was the creation of the Newlyweds Park, based on the idea that newlyweds select and pay for a tree which would then be planted in the Newlyweds Park (Blažević, 1976). However, this widening of participation int he planning process also had its setbacks and ultimately led to a lack of planning control that great impacted urban green space. For example, in the 1970swhen the number of cars in the city started increasing, there was not enough parking space. Through legal means, but more often than not illegal recourse, parking lots and garages were constructed on the edges of urban parks, which impacted their size and quality. Authorities were generally aware of the problem, but not having a solution, they usually turned a blind eye on such developments. Today, the impact of this is still visible in Zagreb.

Contemporary Zagreb

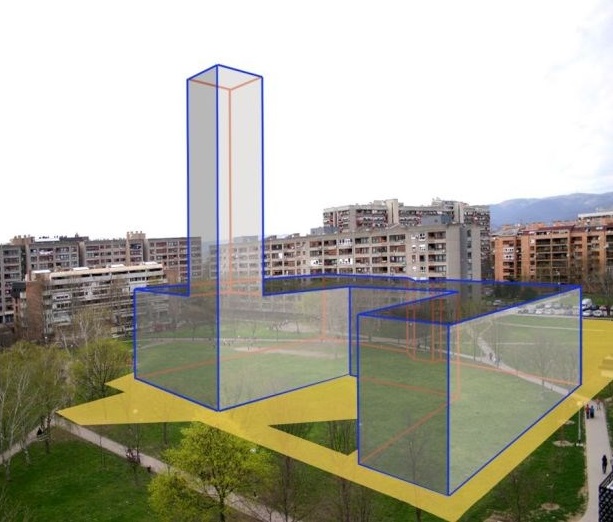

The disintegration of Yugoslavia in the early1990s lead to yet another war that greatly impacted the development of the city of Zagreb. A political, economic and social transition introduced democracy in government and liberal market economy and various nationalised services and departments were transferred to the private sector. The lack of money in city treasury meant that some public projects could not be done exclusively by the city and needed the involvement of private investors. That often included granting some rights to private investors over the public space at the expense of public rights. Moreover, the new system allowed the private-sector-led transformation of public space, like urban parks, into commercial or residential functions. This sparked discontent among the citizenry and lead to people self-organising against these public-private initiatives to redevelop greenspace. For example, one recent initiative rallied around the preserving the only park in the Savica quarter from joint city authority, and private sector plans to build a church in it (Kramarić and Lisac, 2017).

Today, there are hundreds of various green spaces in Zagreb. While the most famous and central ones are well-maintained, the other ones, especially those further from the centre, are not cared for as well. Moreover, in distant districts green spaces are frequently of poor quality, they often lack landscaping, biodiversity and are mostly just plain grass lawns, and are used mostly by dog owners. Contemporary greening ideas appear to focus mainly on accommodating tourists while incorporating incorporate the longstanding mayor’s passion for fountains. There are many examples of newly introduced fountains in Zagreb squares and parks. Perhaps the largest and most expensive such project was the redevelopment of the University Meadow close to the city centre. While beautifying the image of the city, little attention is paid to the inhabitants’ opinion and the functional design of quarters. The light at the end of the tunnel is the strengthening of the civil sector in Croatia which fights its way to influence the planning of public space at the local level and publicly re-examines decisions made by city fathers.

Look at the history to envision the future

Over the last 200 years, greening ideas in Zagreb changed substantially. Urbanisation, influential planning practices such as utilitarian aesthetics (in the 19th century), regime ideology (socialist period), privatisation and personal agendas (post-socialist period) were all factors that greatly influenced the design and development of greenspace in the city. Parks in Zagreb are the result of original ideas and contemporary drivers of each period. While historical circumstances and regimes changed, planners often remained, pulling the values of the previous period and linking it with values of the next period. Most of the time positive aspects remained while the undesirable ones were replaced. By knowing some socio-political history, we can read Zagreb’s parks as a history of ideas of living, recreation, design and values. Moreover, the parks can help us to evaluate new ideas and re-evaluate the old ones in order to come up with functional public spaces. Even past mistakes can help us to learn and improve the planning practices.

Neven Tandarić and Chris Ives

Nottingham

References

Barešić, D. and Sirovec, J. (2011) ‘Rokov perivoj u Zagrebu’, Prostor, 19(1), pp. 184–199. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=63030750.

Bašić, K. (1989) ‘Unutargradski prerazmještaj stanovništva kao pokazatelj funkcionalno-prostorne transformacije Zagreba’, Acta Geographica Croatica, 24, pp. 69–84.

Blažević, M. (1976) ‘Uvod’, in Uloga i značaj zelenila za stanovništvo Zagreba i njegove regije. 1st edn. Zagreb: Stablo mladosti, pp. 8–10.

Kiš, D. (1976) ‘Drvo u gradu – faktor zaštite čovjekove okoline’, in Uloga i značaj zelenila za stanovništvo Zagreba i njegove regije. 1st edn. Zagreb: Stablo mladosti, pp. 35–44.

Kramarić, I. and Lisac, R. (2017) Slučaj Savica – i struka protiv betonizacije parka. Zagreb: Savica ZA park. Available at: http://www.kulturpunkt.hr/sites/default/files/DAZ_SLUCAJ_SAVICA-podrska_struke.pdf.

Matković, I. and Obad Šćitaroci, M. (2012) ‘Rijeka Sava s priobaljem u Zagrebu; Prijedlozi za uređivanje obala Save 1899.-2010.’, Prostor, 20(1), pp. 46–59.

Simmie, J. M. (1989) ‘Self-management and town planning in Yugoslavia’, The Town Planning Review, 60(3), pp. 271–286.

Slukan Altić, M. (2012) ‘Town planning of Zagreb 1862-1923 as a part of European cultural circle’, Ekonomska i ekohistorija, 8(8), pp. 100–107.

about the writer

Chris Ives

Chris Ives takes an interdisciplinary approach to studying sustainability and environmental management challenges. He is an Assistant Professor in the School of Geography at the University of Nottingham.

Leave a Reply