(This is a recasting of an essay of the same title recently published in the limited circulation Ecocity World newsletter)

“You say you want a revolution

Well, you know

We all want to change the world

You tell me that it’s evolution

Well, you know

We all want to change the world”

—Lennon & McCartney 1968

We can, but we need to pay attention to where ideas come from and how they have been understood in different ways. For example, Charles Darwin’s work was co-opted to serve the ideological spirit of capitalism when Thomas Huxley focused on the competitive “red in tooth and claw” aspects of his theory.

But as, neatly summarised by Nigel Barber, the dominant feature of evolutionary behaviour is actually cooperation. Alfred Russell Wallace, co-discoverer of Evolution, wrote that. . .”the popular idea of the struggle for existence entailing misery and pain in the animal world is the very reverse of the truth. What it really brings about is the maximum of life and of enjoyment of life with the minimum of suffering.” Forty-two years after The Origin of Speciesthe great Russian anarchist geographer Prince Petr Kropotkin wrote Mutual Aid (1902) in response to Huxley’s brutally competitive take on evolution to demonstrate through a series of case studies and reasoned arguments that cooperation is normal in nature.

But as, neatly summarised by Nigel Barber, the dominant feature of evolutionary behaviour is actually cooperation. Alfred Russell Wallace, co-discoverer of Evolution, wrote that. . .”the popular idea of the struggle for existence entailing misery and pain in the animal world is the very reverse of the truth. What it really brings about is the maximum of life and of enjoyment of life with the minimum of suffering.” Forty-two years after The Origin of Speciesthe great Russian anarchist geographer Prince Petr Kropotkin wrote Mutual Aid (1902) in response to Huxley’s brutally competitive take on evolution to demonstrate through a series of case studies and reasoned arguments that cooperation is normal in nature.

Our cities, for all their faults, rely on cooperation and shared endeavour to exist at all. The converse truth of the fact that occasional murders and obscene events are headline news is that they are sufficiently rare to make the headlines on a planet of over 7.6 billion people.

Our cities, for all their faults, rely on cooperation and shared endeavour to exist at all. The converse truth of the fact that occasional murders and obscene events are headline news is that they are sufficiently rare to make the headlines on a planet of over 7.6 billion people.

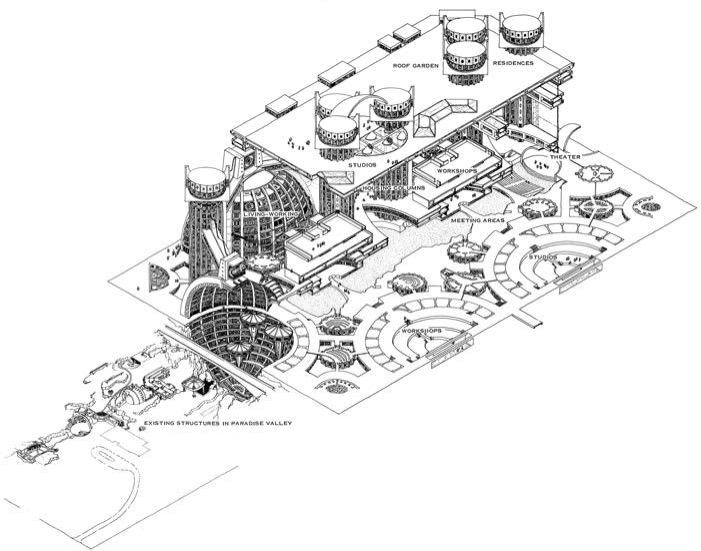

In 1915, over a century ago, Patrick Geddes published Cities in Evolution. Fifty years later, the flawed visionary Paolo Soleri presented his “arcology” (architecture + ecology) conception of cities as a tool of evolutionary progress. My first exposure to his marvellously outrageous ideas was as a student at the Welsh School of Architecture in the early 1970s; I had a “Soleri phase”, as I rather gracelessly told him when I was able to interview him during my sabbatical in Phoenix in 1990. For a little more background on Soleri and his influence by the radical evolutionary theology of Teilhard de Chardin see my previous TNOC article “Half Earth Cities”.

Soleri

Soleri’s concept of cities as evolutionary tools was predicated on the idea that human mind and spirit could be developed and perfected by creating an appropriate physical environment. Observing a correlation between density and complexity and noting that greater levels of intellectual and spiritual endeavour arose from denser congregations of people in cities, his proposition was that the denser the city, the greater the number of interactions there would be to amplify the collective mind power and spiritual awareness of the congregation. At the same time, with less physical space required by urban systems they would be more efficient, and the ecosystems of the natural world could be released from the consumption and denaturing of the landscape by sprawling suburbs.

His was an extreme vision, but it favoured the growth of consciousness and the health of living systems over profit and the perverse ideas of what constitute “development” that we’ve all become used to. Although Soleri’s efforts to physically manifest his vision are restricted to a handful of buildings in the Arizona desert, he has been responsible for one of the great thought experiments linking urbanism with evolution and has produced important insights, like the now largely accepted view that urban sprawl is antithetical to healthy landscapes.

Register

Despite these ideas being around for some time, they are not at the heart of modern discourse about what cities are and what they can do for the natural world. Richard Register’s proposition that ecocities should be places where the great human invention of urbanism should be set in balance with nature shifted the ecocity idea from the spiritual vagaries of Soleri to a more concrete goal of working with nature to enable people to meet all their needs and be healthy, happy and fulfilled at the same time as maintaining the functions of natural systems that are crucial to the continuation of life.

There is nothing intrinsically “smart” or technologically advanced about this line of thinking – which is one of its great strengths (I am reminded of Lloyd Kahn’s “Smart but Not Wise’” essay from the early 1970s here he makes the distinction between smart and wise, it’s an observation that has stuck in my mind ever since). The human settlement that is established and maintained within the limitations of its immediate environment achieves almost complete ecocity status and fits the definition of wise, rather than smart. It is worth recalling that amidst all the rhetoric and advocacy about the wonders of a smart new digital world, that technology can help or hinder and smart can be nurturing or lethal. One thinks of smart bombs and weaponised drones.

Ecopolis

As I’ve pondered these ecocity concepts over the years I’ve become fascinated and increasingly disturbed by the realisation that cities are epicentres for the destruction of the natural world.

Drawing on everything I’d read, seen and believed about cities I have long since come to the conclusion that there is something crucially important about the idea that cities, evolution, human development, and protection of the biosphere are intrinsically linked and that it deserved a great deal more attention and focus intellectually, philosophically—and in practice. I explored this in some detail in my book Ecopolis: architecture and cities for a changing climate (2009). What does it mean to say that a city is an evolutionary tool? How do these concepts interact?

In an attempt to link these strands of sometimes divergent thought, looking for the points of connection in what Gregory Bateson might have called “the pattern that connects”,I put together a set of propositions.The propositions describe cities and their relationship to both the biosphere and human culture and lead to a tolerably concise definition of the purpose of cities—which is to create and manage complex living systems that are the primary habitats for human survival. It seems to me axiomatic that human survival depends on the integrity of the natural world. Much of the following is taken directly from my 2009 book Ecopolis.

The term Ecopolis is drawn from “eco” (strictly, from the Greek oikos, or house, but conventionally understood to mean ecological) and “polis” (which Lewis Mumford describes as a self-governing city “where people come together, not just by birth and habit, but consciously, in pursuit of a better life”). Thus eco refers to ecological purpose and polis to the ideas and ideals of governance that encompass community and self-determination. I adopted the term in 1989, constructing the word from first principles. It has been independently discovered or constructed around the world: in late 1970s Russia (according to Ignatieva 2002), in Finland (according to Koskiaho 1994), in Italy (Magnaghi 2000), adopted by others (Girardet 2004), and it has been used to name conferences in Russia (1992), China (2004) and New Zealand (2004).

Although Ecopolis is about creating human environments specific to their time and place, the concept is timeless and universal. To make places for everyone, in every land, for all time, cities need to be different, reflecting the characteristics of people, place and processes unique to their place and time. This “universal regionalism” can only come about through the consistent and persistent application of principles embedded in an explicit culture of city-making. The challenge is to embed processes in the life of a city that are as natural to it as bones are natural to our bodies. Fully realised, Ecopolis is a manifestation of a developed ecological culture, standing in contrast to the expressions of exploitative culture that are our present-day cities.

Municipalism

At the beginning of the Twenty First Century Alberto Magnaghi and the Italian “Territorialists” proposed a “New Municipalism” which is very close to the Ecopolitan idea and bears strong influences from Murray Bookchin and his Municipal Libertarianism. It deals with what Anitra Nelson might call “the grainy level of community-inspired action” (Nelson 2007) and has more to say about citizenship and the purpose of cities than New Urbanism. It offers much more than prescriptions for civic pleasantries and transit-oriented commuting. Partly, this reflects the birthing environment of the ideas. The New Urbanists are largely from (and a much-needed reaction to) the New Worlds which spawned mindless sprawl, soul-less shopping centres and big boxes of possessions masquerading as homes. The European Territorialists are from the Old World, where enough remains of pre-consumerist, fine-grained, functional, equitable humanist urbanism and its relationship to the productive landscape that the recent dominance of industrialism and the motor vehicle can be placed in the perspective of a deeper historical context. When it comes to interpreting the patterns and purposes of the urban and the rural, the New Urbanists are, at heart, traditional modernists. The Territorialists are radical traditionalists.

The making of architecture and cities is not something we choose to do, as if there was something else we might do instead, it is fundamental to our nature and as essential to our capacity to procreate and thrive as nest-making is to birds. Until the development of modern human civilisation, there had never before been a situation in which a single species so dominated the planet’s biota, taken up so much of its productive potential or affected so many of its ecological processes. We have achieved this dominance and its associated impacts by city-making and its associated processes. As we learn how to deal with managing the consequences of climate change and come to terms with our role as the planet’s dominant species, we must understand how this phenomenon of building cities is central to our survival.

The purpose of the city must be to create an environment that generates health and enhances sustainability. This is a major historical shift, but the city has the power and reach to achieve it, for as Ian Douglas observed 35 years ago, in 1983: “The urban eco-system is the most elaborate geographical control-system or integrated resource-management system in human experience.”

A city is more than the sum of its buildings; it includes services and infrastructure, hinterland and agriculture that its inhabitants use to consume energy, resources and land. The making and maintenance of cities creates the greatest human impact on the biosphere and it is vital that we understand their processes and purpose. Because cities are the drivers of environmental degradation the challenge is to turn them into agents of ecological restoration, supporting massive human populations and simultaneously repairing the damage to the world that humans have already done. The survival of our species’ civilisation depends on how we make our cities work.

What are cities?

Cities are what we have been making for nearly 10 millennia without regard to environmental consequences; an Ecopolis or, if you will, a fully developed ecocity, creates an environment that generates health and dynamic ecological stability. I propose that successful city-making is about the construction of living systems and that a truly “ecological” city is exemplified in an urban system through which biophysical environmental processes of a region are sustained through conscious intervention, active engagement and collective management by its human population. In other words, the citizens of the urban ecosystem seek to fit human activity within the constraints of the biosphere whilst building environments that sustain human culture. Defined by the need to minimise ecological footprints (biophysical) and maximise human potential (human ecology) to repair, replenish and support the processes that maintain life, Ecopolis is about process; about the cultural patterning of the way we organize knowledge and how we see ourselves.

A city is primarily a place of culture and for the sake of our own survival we must rapidly evolve a culture capable of constructing cities as urban ecosystems that make a nett positive contribution to the ecological health of the biosphere. Even more than this, on a planet so thoroughly urbanised, with every function of the biosphere in some way mediated by its engagement with urban systems, the capacity of the biosphere to sustain civilised humans depends upon the nature of our civilisation. Cities need to be consciously designed and understood as living systems embedded in the processes of the biosphere as key regulators of the global ecology and, I would now add, sentinels for achieving the goal of E. O. Wilson’s Half-Earth project, which is a call to conserve half the Earth’s land and sea in order to provide sufficient habitat to safeguard the bulk of biodiversity, including ourselves.

I’m not a Marxist, but Karl Marx was a first-class analyst and in true Marxian (or is it Hegelian?) fashion it seems to me that there might be some logic in the idea that if cities were the centres of destruction they could and must become the tools for reconstructing and healing the biosphere. From this it is arguable that the ecocity is an evolutionary tool—remembering that evolution can go in any direction. In EcopolisI set out a number of propositions built around that idea.

The Ecopolis Propositions

The ability to transmit in symbolic forms and human patterns a representative portion of a culture is the great mark of the city: this is the condition for encouraging the fullest expression of human capacities and potentialities…

—Mumford 1961

Fitting Cities

We need cities that fit their purpose as global pattern makers and provide fitting places for the realisation of the best of human aspirations. We need cities that generate and are generated by appropriate cultural patterning for achieving this, including the way we organize knowledge and manage human affairs. The over-arching proposition and underlying theme for the following set of Ecopolis conditions is simply that cities are the means by which civilised societies achieve a physiological fit with the biosphere.

I propose that these are the 4 conditions that form the basis of ecopolis.

Proposition 1: CITY-REGION: City-regions determine the ecological parameters of civilisation

- Cities must be regarded as habitats for human survival and evolution.

- Cities are places for procuring, managing and distributing resources for the mutual benefit of their inhabitants and are inseparable from their hinterlands.

- Human impacts on the processes of the biosphere are mediated by land-use patterns that achieve their quintessential expression in city-region morphologies and processes.

- Cities, through their immediate and associated impacts (especially via its coevolved cousin agriculture) are the primary means by which humans act on the biosphere.

- An Ecopolis is an urban system consciously integrated by its community into the processes of the biosphere in order to optimise the functioning of the biosphere for human purposes and for the health of all other organisms.

Proposition 2: INTEGRATED KNOWLEDGE: Ecocity concepts generate an imperative to integrate extant knowledge

- The concepts, principles and techniques that are required to create human settlements that fit within the ecological systems of the biosphere whilst sustaining their biogeochemical functionality already exist.

- Concepts, principles and techniques already exist which are capable of creating urban systems consciously integrated into the processes of the biosphere in order to optimise the functioning of the biosphere for human purposes and the health of other organism, but they are not yet embedded in a cultural framework (arts, sciences, humanities, vernacular and popular culture) that integrates and facilitates their application in the design, development and maintenance of such systems.

- Architecture and urban design are major components of culture and must be conceptually expanded as part of a life sciences approach to recognising the central place of human settlement as an evolving agent of change in the biosphere.

Proposition 3: CULTURAL CHANGE: Creation of an ecological civilisation requires conscious, systemic cultural change

- The collective consciousness and unconsciousness of human inter-relationships with the biosphere is embedded in culture.

- An Ecopolis cannot exist except as the consequence of the creation and maintenance of a society capable of sustaining the responsiveness necessary for managing such a settlement.

- The inter-dependent nature of elements in urban ecosystems requires communication and decision-making structures based on mutual aid—which recognises inter-dependency, and direct democracy—which shortens channels of communication, improves information flow, and more closely relates decision-making to place.

- The foundations of society are cultural and lasting social change depends on deep levels of cultural change.

- To create ecological cities in the form of Ecopolis it is necessary to effect cultural change.

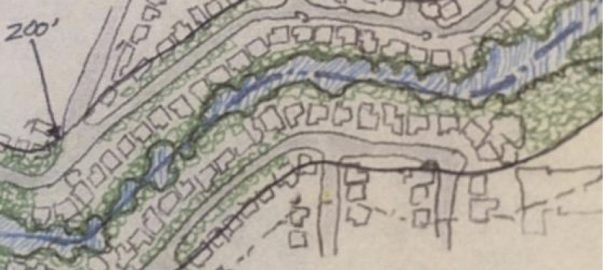

Proposition 4: URBAN FRACTALS: Demonstration projects provide a means to catalyse cultural change

- Changes in city making can be catalysed by demonstration projects of ecocity fractals.

- A living system of human relationships that displays the essential characteristics of the larger culture of which it is a part can be thought of as a ‘cultural fractal’.

- Cultural change can be catalysed by the creation of cultural fractals that display essential characteristics of the preferred cultural condition.

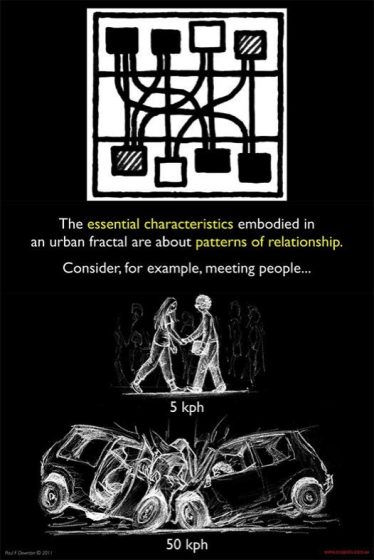

- An ‘urban fractal’ is a network that contains the essential characteristics of the larger network of the city. Each fractal will possess nodes, or centres, and patterns of connectivity that define its structure and organisation, and it will exhibit characteristics of community associated with living processes. It is a particular type of cultural fractal.

- Ecopolis demonstration projects must be urban fractals, containing sufficient characteristics, in process and form, to represent a whole in microcosm (see my 2012 essay for TNOC).

- These catalysing urban fractals can only be brought about with a high level of participation from the community in their design, development and maintenance.

- That participation represents the conscious engagement of the human community with the urban ecosystem of which it is a part.

Register found that the urban fractal idea “describes very well” his own “integral neighborhoods” and “ecological demonstration projects” (Register 2006), and supports the idea that an urban fractal as “a fraction of the whole city with all essential components present and arranged for good interrelationship with one another and with the natural world and its biology and resources for human activity” and because such fractals are only a small fraction of the size of a whole town or city they are much more achievable than whole new cities, particularly in developed countries.

Register found that the urban fractal idea “describes very well” his own “integral neighborhoods” and “ecological demonstration projects” (Register 2006), and supports the idea that an urban fractal as “a fraction of the whole city with all essential components present and arranged for good interrelationship with one another and with the natural world and its biology and resources for human activity” and because such fractals are only a small fraction of the size of a whole town or city they are much more achievable than whole new cities, particularly in developed countries.

Fractal Trim Tabs make differences

Looked at from the point of view of information theory, Gregory Bateson might have said that an urban fractal is a physical manifestation of a cultural pattern that is sufficiently different from the norm to change the deeper pattern of the city. It is, systemically, sufficiently different to make a difference. It is also a device that fits the definition of Buckminster Fuller’s “trim tab factor”.

An urban fractal acts as a trim tab to the larger society and its patterns of urbanism, turning the direction of development of a part of the city so that the direction of development of the whole city is affected, with the whole city, in turn, redirecting the evolutionary arc of the larger civilisation of which it is part.

It was in 1983 that a singular experience brought home to me the capacity of urban civilisation to consume its hinterland. I was working in Jordan as a lecturer in architecture at Yarmouk University, which was an unforgettable and, overall, positive experience that taught me a great deal about any number of things but especially the nuances of different cultures. Chérie (later to be the key organiser of the EcoCity 2 conference in Adelaide) and our young family of three kids had joined me there and we typically spent weekends exploring the countryside, meeting local people and getting to know the ancient and pivotal history of this place—one of the world’s most fascinating countries. A friend who was in the Royal Jordanian Airforce was one of our informal guides and on one occasion he took us to the old stone building of Qasr Amra sitting out on the gibber plains of north-east Jordan. The sun was setting by the time we got there but there was enough light to go inside the building, which hadn’t been dressed up for tourists at all and we were able to make out the hunting scenes painted on its walls. It had been built as a hunting lodge and it used to be surrounded by the forest and its animals that were the subjects for the paintings that, although faded, still decorated its interior. Stepping back outside of that building we were in the middle of one of the most barren landscapes I’d ever seen.

What had happened?

When the Ottoman empire was pushing its way across the region a century before it had constructed a railway line southwards from Turkey and in making the line, timber was hewn from the forest (that used to be there) for railway sleepers and to feed the furnaces to fire the boilers of the steam engines that took the timber to build their cities. We could see that there was now barely any sign of the railway, and no sign of the forest and its denizens. Civilised consumption had struck it all down and all that remained was the evidence of an empty stone hunting lodge and its fading murals.

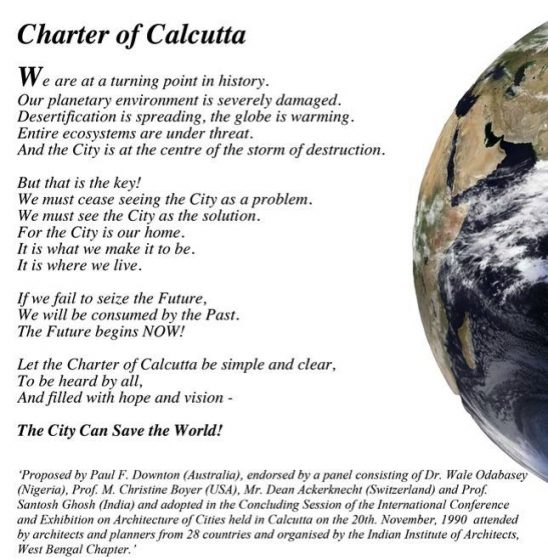

A few years later, after we had emigrated to Australia and after I had spoken at the First International Ecocity Conference in Berkeley in April 1990 (where I met Richard and our friendship began), I was a delegate and speaker at the 1990 International Conference and Exhibition on Architecture of Cities in Calcutta, India (which came about through my acquaintance with Professor Santosh Ghosh that began during my two years in Jordan). By then I had done some considerable research into the impact of cities and urbanisation and concocted a summary statement for the conference declaration that became The Charter of Calcutta.

The 1990 Charter remains my most succinct summary of how I view the impact of cities, both their capacity for damage, and their potential for hope and regeneration.

The 1990 Charter remains my most succinct summary of how I view the impact of cities, both their capacity for damage, and their potential for hope and regeneration.

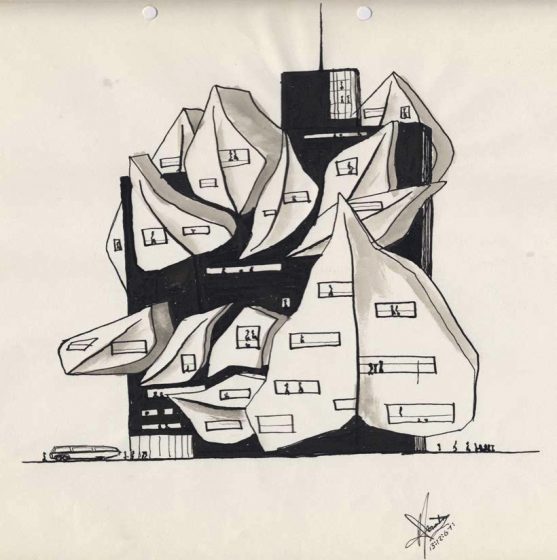

Twenty-three years earlier in my fourteenth year on this planet, I drew a tongue-in-cheek image of a “green” building that was a prescient commentary on what I now think about much so-called ‘sustainable’ architecture. Given that the fundamental shift in thinking needed to get beyond image-mongering to real consideration of ecological and social function in architecture and urbanism has barely begun, the concept of evolutionary cities is nothing if not ambitious.

Evolution appears to be purposeful because it produces results that are fit for purpose but there is no evidence that there is anything at all conscious about the way it proceeds. Which is where we come in (see the Ecopolis Propositions, above). The more we understand about how evolution works, the better the chances are that we can augment, anticipate, facilitate or mimic evolutionary processes and work towards a state of conscious evolution. But we must be aware of what we are conscious of. Evolution is not equivalent to progress. We humans are constantly presented with choices that are pertinent to the future of our species. Do we choose war or peace, murder or life? Etc… These are evolutionary questions where choice can be the agent of destiny. Do we want to be a war-like species or peace loving? Chimp or Bonobo? And how do we build to accommodate that decision?

When evolutionary processes arrive at solutions which survive they are, one way or another, highly effective and place specific. They result in designs that are fit for purpose. If they weren’t they wouldn’t survive. That will always be the measure of anything that lays claim, as I believe we must, to the idea of consciously evolving ecological cities. As our ideas evolve, so must our cities, and given the perilous state of the biosphere it needs to happen with extraordinary and urgent rapidity.

Paul Downton

Melbourne

Add a Comment

Join our conversation