about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

For many in The Nature of Cities community, a key objective or goal could be stated something like this: to empower cities to plan for a positive natural future. There is a lot of unpack in such a statement. Indeed, almost every word in the phrase “to empower cities to plan for a positive natural future” could benefit from some discovery.

“Empower”? What’s the action? Empower whom to do what? What knowledge would ground and justify such empowerment?

“City”? Where? How big? Is there one thing we might call a “city”? Or do we mean “community”?

“Natural”? What elements of “nature” do we emphasize and value? Wild nature? Built nature? Nativeness or functionality?

And so on…

This roundtable is a follow up to a new report called “Nature in the Urban Century”, in which TNOC was a modest partner. You can see the whole report here. The emphasis of the report is on biodiversity conservation, its goals and strategies, and its emergent benefits for people.

The partners of this roundtable—TNOC, The Nature Conservancy, and Future Earth—wanted to cast a wider net of responses to this topic, so we asked a diversity of people in the TNOC community to respond: architects, artists, activists, academics and practitioners, and people from the north and south. Their prompt: What is one specific action that should be taken (when? immediately?) to achieve a “positive natural future”? And who should do it? We asked them to feel free to define “natural” as it suited their argument.

No one would be surprised to hear that from such a diverse group there are a range of responses. Some threads exist, though, and three in particular. The first is “connection”, both of people to a consciousness about nature, and of connecting urban spaces to a wider geographic sense of the idea of “nature”, for example gradients spanning city centers to rural areas. Partly this is data and knowledge, but it also involves a broader awareness. There probably isn’t one “nature”, but we need to address the idea of this word directly and explicitly with a wide range of stakeholders.

A second thread is “diversity”, recognizing both its bio- and also human expressions. This emerges from recognizing cities as ecosystems of people, natural spaces (both wild and built), and infrastructure—all of these things. A key element in recognizing and honoring diversity is in truly engaging diverse stakeholders, from real participatory actions to finding new ideas from various sources, not just the usual collection of “experts”, such as professional ecologists, planners, and designers.

Third, there is a deep thread of “equity” and “justice” in these responses. That is, in our conversations about nature and cities we must always be demanding about spreading the wealth and benefits of nature so that everyone may benefit.

In other words, If there is going to be a positive natural future, we’ll only achieve it together.

about the writer

Graciela Arosemena

Graciela Arosemena is a Researcher and Professor of Urban Open Spaces at University of Panama, Panama, and the author of “Urban Agriculture: Spaces of Cultivation for a Sustainable City”.

Graciela Arosemena

In cities close to natural areas, the continuous growth and urban dispersion has generated great negative impacts on biodiversity, fragmenting habitats and causing spatial interruption, and the reduction of the quantity and diversity of species.

The need to achieve a balanced coexistence between urban environments and natural ecosystems is evident. Understanding as natural, a multisensory reality, synonym of greenery, and pure air, but also of respect and a high degree of commitment on the part of the cities to conserve.

A fundamental strategy for empowering cities and guiding them towards a positive natural future is to develop a model of the city that contains the growth of the urban sprawl, through re-urbanization, which must be assumed by policy makers and urban planners, of local governments; and although its execution is developed in the medium and long term, from now on, urban studies must be started to develop it.

This strategy constitutes the process of rearrangement of the existing urban fabric that may include the accumulation and new subdivision of lots, the demolition of buildings and changes in the infrastructure of services and population density. This process is based on demographic forecasts, and the promotion of the compaction of urban fabrics, prioritizing their recycling. Through the study of the existing urban sprawl, areas of renewal of the urban fabric can be defined, leaving the natural spaces and/or those with potential to be regenerated around and through the urban fabric.

In anticipation of the growth of the city, there is no commitment to extend the limits of it, the re-urbanization avoids the unnecessary occupation of new land, which in many cases is natural, for urban uses, so that an effort is made to a rational and efficient use of urban land. In addition, it contributes to ordering the globalization of undeveloped land, to maintain the ecological permeability of the territory, and to avoid the isolation of natural spaces.

about the writer

Marcus Collier

Marcus is a sustainability scientist and his research covers a wide range of human-environment interconnectivity, environmental risk and resilience, transdisciplinary methodologies and novel ecosystems.

Marcus Collier

There is a lot of concern that urban dwellers in the future, especially in very highly populated cities, will have considerably less “access” to nature, especially wild, unkempt nature. Indeed, there are similar concerns on whether people will have any access to nature, wild or otherwise. The negative effects of this on humans (socially, cognitively, and physiologically) are likely to be significant with respect to population health and well-being. Considering that the urban poor will be disproportionally impacted by this may also give rise to political and social issues. So, there is a demand for more diverse nature in cities, something that The Nature of Cities has been championing for many years now. There are many other champions for nature in cities, and one of the approaches of the European Union is to stimulate the scaling out of “nature-based solutions” partly as a response to this and partly to stimulate innovation in city-making. We know that urban green infrastructure such as parks can provide valuable ecosystem services, such as flood attenuation and improving air quality. The nature-based solution approach takes this further. It sees nature as a technology; one that can have multiple environmental, ecological, social and community gains. Typically, nature-based solutions manifest themselves as living roofs or living walls, rain gardens, nutrient interceptors, etc.; engineered (nature-based) technology that essentially exploits a few billion years of natural R&D to address the complex and the ever-accelerating impacts of environmental change in urban areas. Not that we needed another reason for bringing more nature in to cities, but what “nature” in nature-based solutions are we talking about?

Current technology sees it necessary to populate your typical living wall with evergreen plants that can provide the service of intercepting noise, dust and airborne chemicals; specialist plants that are tolerant of the disrespect and abuse that city living brings. The same goes for rain gardens which are often planted with species selected to tolerate drought and flooding, sometimes on a daily basis! However, will any animal find a living or a home in this new urban and urbanised nature? What of the desire for increasing urban biodiversity? A living wall or rain garden is constructed to do a job and provide at least one service. Therefore, like their counterparts in the rural landscape, for example food crops, will the management of these service providers be similarly anti-nature, as it has been with a myriad of complex chemicals for decades? To keep our living walls doing their jobs effectively, and to ensure no competition from the more common urban botanical urchins (or “weeds”), living walls and rain gardens may need some intensive management that is counter to the intention of providing a more diverse urban nature. Following the food crop analogy, it is logical to propose that we may seek to modify our new urban nature to do its “job” better—engineering our plants to be better nutrient interceptors, carbon absorbers, air filterers, and water attenuators. And with the importation of a new community of street-wise botanical service providers into our growing, densifying cities, there is also the possibility of some of them escaping” and the invasive species debate hots up once more.

Living roofs have taken a step in addressing this. No longer referred to as green roofs (a monocrop of sedums) they are now “living” and more biodiverse in species and structure. This is great for urban invertebrates and some birds, and at certain times of the year biodiversity is colourful and soul-lifting against the grey of the city. At other times of the year, however, this new “wild” can be ugly and depressing; such as when plants go dormant for the winter. So now your expensive living roof looks more like an abandoned and unkempt weed patch. Again, the “nature” of nature-based solutions can problematic. No doubt, social opinions may change as the technology of nature becomes more and more prevalent in cities, but whatever we decide, nature in cities may not necessarily be the nature we remember fondly from the past, if we remember it at all. It may be a sort of hybrid nature, botanically selected and modified, as it always has been in parks and gardens, for tolerance, aesthetics and functions. And just like parks and gardens, over time this hybrid nature may become the new normal in cities.

So, while we desire a greening of our cities on emotional and personal levels, and while we become more reliant on the services of nature to address environmental change and stimulate innovation, the nature-based solution approach has a long way to travel.

about the writer

Marlies Craig

Marlies Craig, pictured in her own indigenous city-forest-garden, is the author of What Insect are You? Entomology for Everyone. Currently she works as a science officer for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Marlies Craig

Trees in cities hold great potential for their cooling properties and carbon sequestration, for ground stabilization and water absorption, biodiversity and biophilia, food and fuel, etc. In Durban, South Africa, tree planting is also transforming the lives of marginalised and unemployed people from some of the most impoverished and vulnerable areas.

So-called “tree-preneurs” collect and grow the seeds of indigenous trees. The small saplings are then bartered for credit notes, which can be used to obtain food, basic goods and/or pay for school fees. The trees are used to afforest the buffer zone of a municipal landfill site, previously under intense sugar agriculture or overrun with invasive alien plants, with fantastic biodiversity outcomes.

The Buffelsdraai Community Reforestation Project is a model of effective collaboration between local government, environmental NGOs and civil society, resulting in multiple benefits for climate change mitigation and adaptation, biodiversity, the environment, human communities and the local economy.

Through similar mechanisms the entire city could be “greened” by planting suitable indigenous trees, shrubs or grasses on unused land, company gardens and verges, so they line roads, dot car parks, blanket suburbs.

Unfortunately, urban greening is often achieved with exotic species. Even if, according to UBHub 94% of urban plant species are native, the bulk of biomass (if you could put the plants on a scale) may not be. Johannesburg for example is known as the largest exotic forest; on satellite images it registers as tropical rainforest. Cities can be turned into carbon-dense forest-equivalents with obvious multiple benefits, but non-indigenous “urban forests” are a wasted opportunity, as they do not suitably support local biodiversity.

In the food web the vast majority of consumers are invertebrates—insects mainly. Among the vertebrates, the vast majority eat invertebrates—again, insects mainly—at least sometimes or at some stage of their life: most birds, about two thirds of mammals, virtually all amphibians, reptiles and freshwater fishes.

Plant-eating insects are therefore the main link between plant producers and animal consumers higher up in the food chain. And interestingly, the vast majority of these small, six-legged herbivores eat only one or two different plant families, or even species. What is more, around 88% of plant species (78% in temperate, to 94% in tropical zones) in turn depend on animals for pollination (and thus survival)—either insects, or insect-eating birds and bats.

Biodiversity (in terms of species) is underpinned by a diverse indigenous flora sustaining a myriad of harmless insect specialists, which in turn keep the food chain going. Exotic plants benefit only a small number of generalists.

In cities, where ground space is precious, indigenous trees provide the above-ground biomass required to sustain local insect populations large enough to feed sustainable bird populations. The birds, while keeping insect pests in check, also bring in their droppings the seeds of more plants (trees, bushes, flowers) which then attract more harmless insect species, fueling a wonderful upward-spiral of biodiversity.

about the writer

Samarth Das

Samarth Das is an Urban Designer and Architect based in Mumbai. Having practiced professionally in Ahmedabad, Mumbai, and subsequently in New York City, his work focuses on engaging actively in both public as well as private sectors—to design articulate shared spaces within cities that promote participation and interaction amongst people.

Samarth Das

Taking national level projects as precedents, nature—in all its forms—is severely compromised in most Indian cities. The issue is compounded several fold in the case of the urban metropolis of Mumbai. Essentially an estuary, the city has grown over the years by way of constant land filling and consolidation. This makes the city highly vulnerable to sea level rise and flooding. Mumbai city has a rich and vast extent of natural assets, measuring approximately 140 km2 including rivers, creeks, nullahs (natural storm water channels), mud flats, salt pans, wetlands, mangroves, lakes, hills and forests. We all know how important a role these natural features play in maintaining the environmental balance in and around the city—the most direct advantage of features such as mangroves and wetlands being that they help mitigate the ill effects of storm surges and high tides in extreme weather events.

Unfortunately over the years, the city’s development plan has not taken these natural features into account, which has led to the lack of their integration and consequent degradation.

Sadly, the city has turned its back and considered them as a dumping ground—both physically and metaphorically—leading to their rampant destruction and degradation. Unplanned commercialization has destroyed the natural environment considerably. The absence of a master plan for development of the waterfronts and other natural edges has encouraged the rich and the powerful to manipulate and grab land along these assets.

Map, Map, Map!

The need of the hour in Mumbai is to engage in an intense mapping process of all natural assets and areas in the city. Mapping today, goes beyond its orthodox use where it was deployed for purposes of physical surveying of land. It has become a powerful tool for analysis of current conditions, as well as in predicting future trends across various fields in which they are used. Mapping of the natural areas in Mumbai will serve a larger purpose at this point—it will establish the relationship of these resources in context to our urban environment while lending credibility and authenticity to the claims of those advocating and fighting for their protection. With scarcity of land becoming a go-to excuse for governments and the real estate industry to exploit NDZ (no development zone) lands for housing, mapping of natural areas will help establish what land is “developable” and what land is not. With the city’s new Development Plan for the next 20 years currently in the works, we are at a crucial juncture to ensure the protection and safeguarding of the city’s lungs against ill intentions of the real estate sector. Once mapped, these development plans become a basis for legal standing to challenge abuse and misuse of our natural assets which is missing presently.

This has to happen now.

To be truly effective, the mapping process will require active participation from local administrative bodies as well as from citizens in individual neighbourhoods/areas. Including the various stakeholders in the process of producing and reviewing the maps will increase the sense of ownership and responsibility towards these natural assets right from the ground up. The Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai will need to take the lead in this process. National and State level bodies such as the National River Conservative Directorate (NRCD), the Mangrove Cell and the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF)—who govern various environmental and natural features will need to prescribe the specifics of the mapping endeavor and oversee the process to ensure that basic standards are met. This effort will ultimately need the backing of the State’s Urban Development Department which is tasked with approving and publishing the final Development Plans for the city. We can set a precedent for future administrations, and begin re-gaining lost ground in the race to protect the environment and ensure a sustainable future.

Empowering our cities to plan for a truly positive natural future will require the empowerment of the very natural assets and features that will ensure a sustainable balance between the built and unbuilt environment. Mapping is a socio-political act we must engage in to empower Nature within our cities.

about the writer

Ana Faggi

Ana Faggi graduated in agricultural engineering, and has a Ph.D. in Forest Science, she is currently Dean of the Engineer Faculty (Flores University, Argentina). Her main research interests are in Urban Ecology and Ecological Restoration.

Ana Faggi

In order for these landscapes to function and be resilient in the face of recurrent and surprising changes (which characterize the Anthropocene), it is necessary that the whole community understand that the green and blue infrastructures are not options but essential elements that cannot be negotiated to continue building the city.

For this, the diverse media should address them from the ecosystem services point of view that they provide.

Green is formed by parks, squares, urban forestry, reserves, gardens, green roofs, corridors, vegetation remnants; the blue: all watercourses.

The choice of the green type will depend on the need to make attractive places to live, work or recreate, to meliorate climate and or to improve local natural habitats and biodiversity. Nevertheless, faced with these decisions of what green to create, maintain or conserve, it is fundamental to use native plants, which are found naturally in an area. This will guarantee the balance.

To mitigate the loss of biodiversity due to changes in land use, an action to be implemented would be the obligation of the municipal government to cultivate native and very especially endemic plants, which should be donated to the neighbors. This would reverse gradually, the harmful trends caused by a globalized landscape architecture which are evident in almost all cities.

about the writer

Sumetee Gajjar

Sumetee Pahwa Gajjar, PhD, is a Cape-Town based climate change professional who has contributed to scientific knowledge on transformative adaptation, climate justice, urban EbA and nature-based solutions. I currently work at the science-policy-research interface of climate change, biodiversity and vulnerability reduction, in the Global South. My research interests continue to be focused on urban sustainability transitions, through collaborative governance, just innovations and climate technologies.

Sumetee Gajjar

A suite of solutions is suggested that can help integrate nature into cities. The foremost step offered is biodiversity planning, or greenprinting, to facilitate a combination of efforts including education and communications campaigns about nature, increased direct access to nature, conservation planning and establishment of green and blue infrastructure. Critically, these require the incorporation of biodiversity and ecosystem information into urban planning, busting of institutional silos at local level, which impede integrated planning for future urban growth, and importantly, the alignment of development agendas across different levels of government. Biodiversity planning or greenprinting is presented as the first step towards the next two sets of solutions—integrating nature into the city; and managing protected areas. Nature-based solutions include green infrastructure (including human-designed parks, planted street trees, green roofs) and blue or water management infrastructure (such as bioswales, rain gardens and artificial wetlands). However, land protection is proposed as the most permanent and effective way to safeguard biodiversity.

A city greenprint would speak to urban transport considerations, zoning and affordable housing construction, water management, economic development plans and energy infrastructure. Alongside, it should strengthen disaster management and investment planning within urban areas. The authors suggest inclusion of key stakeholders who are representative of a range of decision-making processes and parallel drivers of urban expansion—both through physical development of the built environment, and population growth—as crucial for a city greenprint, as is with any type of urban planning exercise. Nature-based solutions have clear linkages with eco-sensitive building and urban design and render discernible benefits towards well-being of city residents. Moreover, implementation of particular solutions can be located in brownfield and vacant or unutilised urban plots. However, long-term locking in of land on urban fringes strictly for biodiversity conservation, with controlled human presence, primarily for education, or restricted recreation, would be a harder outcome to negotiate, even with support from higher levels of government, and despite strong evidence proving it as the most effective strategy.

The report finds that while there are several examples of current biodiversity activities by municipal governments such as urban biodiversity reports and plans, these are primarily from the UK, North America and Japan. At the same time, the assessment shows that significant impacts from urban growth on biodiversity in the period under study (2000-2030) have occurred and continue to occur in Asia, Africa and South America. Studies have also shown that biodiversity loss is spatially concentrated, and that targeting key biodiversity hotspots through local planning, could help focusing worldwide efforts on lowering the impact of global urban growth on biodiversity

Therefore, a gap which needs special attention going into the future, led by a specific set of actors, are city biodiversity reports which inform biodiversity planning or city greenprinting process of Asian, African and South American cities or city-regions, experiencing spatial concentration of biodiversity loss. It would include an assessment of current ecosystem health, mandated and approved by government, necessitating collaboration between scientists across a range of natural sciences, and urban planners and practitioners. It can also help align the efforts of citizen groups who demand protection of nature in their cities, by engaging them in the assessment process through citizen science tools, and empowering them to align their efforts, based on scientific evidence.

Authors of the assessment cite governance and capacity gaps, as reasons for why biodiversity reporting and planning lags in regions and cities, which will see the most significant impacts of urban growth on biodiversity planning. To meet capacity constraints, local governments can draw upon and join any number of existing frameworks and programs specific to urban biodiversity. They can then access and apply tools for assessing their biodiversity status, learn how to implement pilot projects and contribute to knowledge networks and platforms, such as those developed and supported by ICLEI, IUCN, and The Nature Conservancy.

about the writer

Gary Grant

Gary Grant is a Chartered Environmentalist, Fellow of the Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management, Fellow of the Leeds Sustainability Institute, and Thesis Supervisor at the Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment, University College London. He is Director of the Green Infrastructure Consultancy (http://greeninfrastructureconsultancy.com/).

Gary Grant

Understanding, embracing, and acting on the sponge city concept, launched in China in 2014, will be the most powerful and effective way that we can increase biodiversity in our cities.

The lack of soil and vegetation and absence of wildlife is largely the result of the replacement of natural features with sealed surfaces. Most people are not concerned with the loss of biodiversity and they are not usually concerned with the problem of sealed surfaces, however there will be an increasing realisation, as climate change brings more frequent and more intense downpours and heatwaves, that the great efforts that were made to pave and seal our cities, for our convenience, have left people vulnerable to flood and the consequences of extreme heat and desiccation. Even those with no appreciation or understanding of nature and wildlife have an interest in adapting to climate change.

Politicians, officials and experts can do their part. Simple guidance, like the Biotope Area Factor, which came of Berlin in the 1990s and is now been adopted in various forms, for example as the Green Area Ratio in Washington DC, or the proposed Urban Greening Factor in London, can ensure that development proposals contribute towards the establishment of the sponge city. These simple ideas are not too prescriptive and encourage innovation. Where people wish to become more sophisticated about the testing of plans and designs for climate resilience through the use of nature-based solutions, they can turn to new software like the GREENPASS, from Austria, which can used climate data and 3D plans to identify problems with schemes and cost-effective solutions.

Although not all efforts to create the sponge city necessarily increase biodiversity or necessarily create the most appropriate habitats or species, a permanent increase in the volumes of soil and water, both on the ground and on buildings, create more potential for ecological restoration, better informed planting and the provision of more and improved natural services, like cleaner water, cleaner air and pollination. The sponge city will bring together a wide spectrum of people to ensure that more soil, water and vegetation is present. Specialists and enthusiasts can fine-tune the methods of planning, design, installation and maintenance.

One of my own experiences with introducing the sponge city concept to a small community was in the small town of Littlehampton, West Sussex on England’s south coast. A public meeting to propose rain gardens was met with some scepticism from some older people who like piped drainage. There were concerns about a lack of funds and the authorities were lukewarm about the idea to begin with. A couple of years later, mainly through the hard work of a few champions, rain gardens have been installed using local schoolchildren to undertake the planting, an award has been won and the authorities are now actively promoting the idea in other towns.

These patterns of bottom-up activism and top-down regulation and guidance can bring about the sponge cities we need and nature needs.

about the writer

Eduardo Guerrero

Eduardo Guerrero is a biologist with over 20 years of experience in projects and initiatives involving environmental and sustainable development issues in Colombia and other South American countries.

Eduardo Guerrero

Are cities part of nature? Is the budget devoted to cities environment a cost or an investment? Does the urban green matters in terms of the economic performance of the cities? Which kind of cities are more competitive: those actively integrating green areas and peri-urban ecosystems to the urban design or those where green and biodiversity are secondary issues? How can we integrate urban green and environmental concepts to entrepreneurship from the beginning in the business cycle?

In fact, cities are built in the middle of ecosystems and biomes, so they are part of regions and territories whose natural attributes should be integrated into urban design and urban economic plans.

In general, in their narratives urban planners and business stakeholders accept the need to reach minimal standards of green and environment quality in their cities, but in practice entrepreneurs do not receive clear policy signals and market incentives to stimulate nature-based and green businesses.

The point is that nature and ecosystems services are drivers of competitiveness in cities. And there is much evidence, pilot projects, and good practices waiting to be systematized, adapted to local contexts, and scaled up.

In rankings of competitivity, environment use to be considered as a minor factor, mostly dealing with the ability to manage hazards and the environmental governance.

Of course, ability to implement environmentally sustainable policies and mitigate the impact of natural hazards is key to cities, but it is just part of the nature-cities equation.

We propose a most constructive approach, oriented to promote synergies among nature and urban economies. When you invest in green infrastructure, sustainable building, a circular economy, urban nature tourism, urban agriculture, biogastronomy, and so on, you are both investing in sustainability and competitiveness.

We propose to arrange a think tank network on urban nature and competitiveness. The objective: to contribute to a plural, multidisciplinary dialogue on green businesses in cities by connecting university-based research capacity to business stakeholders, policy and decision makers and civil society.

There are many good examples of synergies among biodiversity and economy in cities. A lot of good practices in urban and peri-urban contexts showing that business and environmental sustainability could be mutually reinforced. Limitations and restrictions use to be just the result of rigid cultural visions, biased mentalities and poor dissemination of good practices.

Among other factors, Bogotá is a competitive city thanks to the joint work of the national agency for natural parks and the water supply company taking care of the paramo (high sierra) ecosystems that regulate water supply to the city.

If we look around the world, there are other many excellent examples of city economies increasingly based on nature and ecosystems services. In Rio de Janeiro, income from tourism mostly depends on the beauty of its natural landscape, so conservation and sustainable management of natural landmarks as Guanabara Bay, Tijuca Forest, and the magnificent Botanical Garden represent key investments.

Lima is gaining a reputation as a gastronomic destination, because of an enchanting cuisine based on a fusion of cultural and biodiversity ingredients. Nairobi with its safaris to a National Park located around the city is a suggestive destination. London’s inspirational project to be the world’s first National Park City connects very well with its well-earned reputation as a financial center. Bangkok’s ancient culture and spectacular palaces have an intimate relationship with Chao Phraya River, as Cape Town’s traditional architecture establishes a unified relationship with its coastline ecosystems.

Worldwide there is a growing trend towards responsible businesses based on the environment and biodiversity. So green business entrepreneurs need incentives and useful information, the same as authorities and planners need relevant knowledge and data.

So, my proposal is to develop a plural and multidisciplinary think tank network oriented to the relationships between nature and business in cities. Focus would be on concepts, principles, guidelines, and good practices that generate win-win initiatives and entrepreneurship in terms of both urban sustainability and urban competitiveness and productivity.

Of course, many think tanks on urban development matters already exist, but not many connecting urban nature to urban businesses and competitivity

Urban performance and sustainability indexes offer a general image about situation and trends regarding cities development. They invite us to advance from theory to practice in terms of better integrating nature to urban economies.

Who should do it? A think tank network on urban nature and competitiveness should be a synergic and multi-partner action. Maybe The Nature of Citiescould open a thematic line on these matters in coordination with regional, national and local partners and focal points, taking into account nature particular context of each city. We in Colombia would be interested in such an initiative.

about the writer

Fadi Hamdan

Fadi has more than 25 years of international experience in analysing the interaction between development, urbanism, disaster risk, climate change, conflict, and state fragility. Fadi cooperates with various companies, cities, and countries to protect people, assets, and the environment

Fadi Hamdan

In view of the recent publication on urban growth and conserving nature for biodiversity and human wellbeing1, it is important to put such efforts in a wider context.

Human rights-based concepts have occupied the centre stage both politically and ethically, in many cities. However, in many instances these are individualistic and do not necessarily take a collective turn2. On the other hand, thinking of what negative impact of urban growth on biodiversity we are willing to tolerate, is an opportunity to come together collectively, to decide what kind of relations to nature we want to protect and promote. In addition, thinking of how to manage the impact of urban growth on human wellbeing, and how much negative impact on vulnerable people, communities and countries we are willing to tolerate due to the loss of vital ecosystem services, is also an opportunity to decide what kind of societies we want to build, and what kind of urban social relations we strive for.

Therefore the threat that urban growth poses on biodiversity and human wellbeing should also be seen as an opportunity to claim “our right to the city”3, to reinvent the city, based on our vision for the society we want, and our relation to nature. Raising the awareness to recognise this broader opportunity, and the potential of coming together as a result of this recognition, is in my view the single most important action to plan for a positive natural future. This should be done immediately, by all rights-based advocacy and pressure groups, to pressure local and national representatives to allow for a more transparent and participatory decision making process related to the management of urban growth and its impacts on biodiversity and human wellbeing.

In addition to the above, few additional points can be made regarding the recent publication4 on conserving nature for biodiversity and human wellbeing:

- In weak governance and weak environmental governance countries, empowering local governments should extend beyond providing a scientific evidence based tool for local urban planning, together with the institutional and legislative arrangements necessary for the successful implementation of such planning. It should also include an equally important aspect of freeing local governments from narrow vested interests that put the interests of the few above the needs of the many. In other words, the issue of local governance in the broadest sense of participation in the decision making process, needs to be given more attention.

- The advantages of ecosystem services in climate change adaptation and reducing the impact of natural hazards, extend beyond the hydro-meteorological hazards (floods and storms) referred to in the publication, and include other hazards such as earthquakes, landslides and tsunamis. For example, green cover can reduce the impact of tsunamis on vulnerable coastal communities. Furthermore, it can reduce the occurrence of landslides and soil failure after earthquakes.

- The disproportionate concentration of the negative effects of unchecked urban growth on vulnerable and poorer households and communities needs further elaboration. This is particularly important as it can help raise awareness on the opportunity to reclaim our right to the city.

Notes

[1] Nature in the Urban Century, A Global Assessment of where and how to conserve nature for biodiversity and human wellbeing, The Nature Conservancy, 2018. [2] Rebel Cities, From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution, David Harvey, Verso, 2012. [3] The Right to the City, Henry Lefebvre, 1968. [4]Nature in the Urban Century, A Global Assessment of where and how to conserve nature for biodiversity and human wellbeing, The Nature Conservancy, 2018.

about the writer

Scott Kellogg

Scott Kellogg is the educational director of the Radix Ecological Sustainability Center, an urban environmental education non-profit based in the South End of Albany, New York.

Scott Kellogg

Actualizing healthy, just, equitable, and ecologically regenerative urban transformations will require strategic diversity and polycentricism. While it is common in planning circles to favor concentrated, policy-based, and expert driven approaches, equally important and frequently disregarded is the potential of citizen-driven, grassroots, and decentralized initiatives. Although the impact of any individual vacant lot garden, rain water barrel, chicken coop, or compost pile may be small, when multiplied and scaled to a city-wide level their effect is synergistic. Together they significantly build a city’s resilience and adaptive capacity, resulting in a locale where control of resources is distributed equitably among an eco-literate population. Moreover, when sustainability tactics are simple, affordable, and culturally relevant, they are easily transferrable to other locations (Smith, 2014).

To those invested primarily in top-down, command and control approaches to urban sustainability governance, such ideas may be seen as trivial, unworthy of consideration, or even threatening. Their operationalization, however, is an essential first step towards cultivating positive natural futures and the resurgence of the collective urban commons (Nagendra, 2014).

Achieving this goal requires challenging the profound ecological alienation experienced by many city dwellers and the exclusion of the social dimensions of justice, access, and equity from mainstream sustainability discourse. These may both be addressed in part through education.

Environmental education, as conventionally taught in urban schools, frames nature as an abstract concept: something “out there” beyond the city limits that needs to be protected from ourselves. Challenging this nature-culture dualism requires reframing urban ecosystems as complex and dynamic co-evolutionary hybrids of human and non-human processes (Alberti, 2008)—not the hopelessly degraded and un-natural spaces they are commonly conceived as. Furthermore, environmental education must examine how equity, access, class, and race apply to urban ecosystems: what are the historical forces that have led to the exclusion and contamination of urban ecosystems for marginalized populations?

Issues of relevancy and justice may be addressed through an urban sustainability education paradigm named Urban Ecosystem Justice: a framework that aims to cultivate familiarity, care, respect and reciprocal symbioses between urban residents and the soils, waters, atmospheres and non-human life in the urban ecosystem (Kellogg, 2018). It provides whole-systems conceptual lens as an alternative to our educational system’s current obsession with reductionist STEM disciplines.

A few specific examples include:

- Community composting initiatives—regenerating soil health with food waste

- Grassroots soil bioremediation technologies—spent mushroom substrate and compost tea

- Artificial Floating Islands—cleaning rivers with DIY wetlands

- Urban biocultural diversity assessments—valuing ruderal and novel ecosystems

- Citizen-centered air quality monitoring

The work of teaching socially relevant urban ecological education must be carried out in both formal, informal, and non-formal educational settings and be thought of as a form of grassroots activism. With the threats of climate change, energy depletion, pervasive toxicity and increasing inequality rapidly converging, we cannot rely solely on legislative action to bring about needed transformations.

Integral to the urban ecosystem justice approach is a critique of the neoliberal logic that is endemic in many urban planning circles. The practice of viewing cities as “growth-machine” (Molotch, 1976) real-estate investment engines rather than living communities has led to the degradation of the urban commons. Key to their restoration is the extension of the “cities for people, not for profit” (Marcuse, 2012) ethic to the soils, atmospheres, water, and biodiversity of cities.

Opportunity for urban ecosystem justice and commons restoration exists in “shrinking cities” with plateaued or negative population growth (Herrmann, 2016). On account of their reduced real-estate pressures, it is possible to advocate for both urban green space and affordable housing simultaneously—two essential components of urban ecojustice that are often mutually exclusive in hyper-capitalist cities.

In conclusion, positive natural urban futures may be worked towards by focusing on decentralized educational-activist strategies that emphasize human-non human reciprocity, social inclusion, and the reconstruction of the urban commons.

References:

Alberti, Marina. Advances in Urban Ecology Integrating Humans and Ecological Processes in Urban Ecosystems. New York, Springer Science+Business Media, 2008.

Herrmann, Dustin L., et al. “Ecology for the Shrinking City.” BioScience, 2016, p. biw062.

Kellogg, Scott. “Urban Ecosystem Justice: The Field Guide to a Socio-Ecological Systems Science of Cities for the People”. Ph.D. Dissertation. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 2018. ProQuest.

Marcuse, Peter. “Whose Right (s) to What City?.” Cities for People, not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City, New York, Routledge, 2012, pp. 24-41.

Molotch, Harvey. “The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place.” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 82, no. 2, 1976, pp. 309-332.

Nagendra, Harini, and Elinor Ostrom. “Applying the Social-Ecological System Framework to the Diagnosis of Urban Lake Commons in Bangalore, India.” Ecology and Society, vol. 19, no. 2, 2014, p.67.

Smith, Adrian, Mariano Fressoli, and Hernan Thomas. “Grassroots innovation movements: challenges and contributions.” Journal of Cleaner Production 63 (2014): 114-124.

about the writer

Patrick M. Lydon

Patrick M. Lydon is an American ecological writer and artist based in Korea whose seeks to re-connect cities and their inhabitants with nature. He is an Arts Editor here at The Nature of Cities.

Patrick Lydon

Though they may be bad actors at present, streets, housing blocks, and the economy are all inclusive of biodiversity, and of the troupe that we call nature. For this troupe to function properly however, requires a fundamental shift in how we see and experience our cities—and ourselves—in relation to the ecosystems in which we live.

This shift can be plainly put as two (interrelated) points:

- in cities, we need to accept that urban spaces are inextricably intertwined with the rest of nature, and build them in light of this awareness

- as individual human beings, we need to become substantially better at listening to and learningfrom our natural environments

The second of these points necessarily gives birth to answers for the first.

“Study nature, love nature, stay close to nature. It will never fail you.” — Frank Lloyd Wright

Ask our most brilliant scientists, artists, architects, and designers throughout history and you’ll find that a close relationship with “nature” is not only the common fertile ground for creativity and innovation, it is also a critical foundation for growing the kind of nature-connected solutions needed for truly regenerative* cities.

Listening to nature: it’s not just for artists and esoteric philosophers

Having personally spent much of the past decade using an artist’s lens to peer into the mindsets of ecological farmers—both in urban and rural contexts—a comparison of two different approaches to agriculture might help us understand what listening to nature actually means, and why it is important.

Consider that, in Western industrial agriculture, biodiversity most often means creating good conditions for a variety of food plants, while ensuring harmful conditions for weeds, bugs, and most other living things in, around, or downstream of the places where food is grown. At best, this view of biodiversity represents an immature relationship with the natural world. It continues to be accepted today however, even though thousands of years of history—and contemporary biological science—show clearly how harmful it is to our future.

By comparison, on natural farms throughout East Asia—refer to the recent documentary Final Straw: Food, Earth, Happinessif you are unfamiliar with the term—biodiversity has come to mean something far more comprehensive; not only does it mean growing a diversity of foodplants, it also means encouraging a diversity of all other living things in and around the farm, from weeds to bugs.

In the West we tend to question, often harshly, how one could successfully grow enough food to feed humanity without drawing battle lines and waging wars against the parts of nature that seem bothersome to us. However, the truth is that small natural farms throughout the world are growing food more productively, more sustainably, and at less cost to humans and the environment than even the most technologically advanced farms in the United States.

This way of growing food is the result of listening to nature, and of establishing an equitable relationship based on respect, trust, empathy, and acceptance—even for the things we don’t necessarily like. It is also the way to build truly inclusive biodiversity.

If city-building followed a similar prescription, the results would mean positive growth for cities, for people, and for the rest of this nature in which we dwell.

In every neighborhood, a unique representation of biodiversity

What does this mean for cities?

For each individual, each community, each microclimate, the answers will differ greatly. Yet perhaps in this is the answer we are seeking, that our neighborhoods and our cities must become unique representations of natural biodiversity, each one answering to the voice of nature when and where it exists.

Just like a natural farm, or a masterful painting, or a thriving forest.

If we wish for cities to exist harmoniously, sustainably, regeneratively within nature, there is no foundation on which to grow them other than the cultivation of equitable relationships between ourselves, our cities, and the rest of this nature.

Ultimately, it is from these relationships that our best answers will come.

* Regenerative cities go beyond the ‘less pollution, less consumption’ mantra, instead seeing the city and surrounding environment as an organism, and seeking to continually regenerate the health of the whole – people, city, and nature.

about the writer

Yvonne Lynch

Yvonne is an Urban Greening & Climate Resilience Strategist who works with Royal Commission for Riyadh City.

Yvonne Lynch

I believe that meaningful citizen engagement for participation in decision making is the best way to empower cities to achieve their aspirations and goals for a positive natural future. Citizen participation transcends what we broadly understand to be community engagement. Oftentimes our governments deploy public relations strategies masquerading as community engagement activities. They make their own decisions and then summon the community to a town hall meeting, or similar, to discuss their plans. The problem is that there is rarely an opportunity for people to influence or shape those plans. Information provision is not true engagement.

Inviting citizens to co-create from the outset can unearth local knowledge, foster and strengthen community bonds, develop innovative ideas and build widescale community trust in government. If people have an opportunity to invest their time in planning with their governments, they develop a sense of stewardship for their cities and urban landscapes. This sense of community ownership and involvement has the power to overcome the short-term political cycles and related issues that sometimes stifle progress. Community involvement in decisions also provides government with a social licence for the bold moves that need to be made to secure positive natural futures for our cities.

Planning is perhaps the most controversial portfolio for cities. There are generally many vested interests in this arena and the big dollars are always at play. Planning regulations to both enforce increases in urban greening and to protect natural assets are critical for all cities—no exception. There are some wonderful examples of successful planning regulations which have improved development outcomes such as; the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Nature Conservation Ordinance which has resulted at least 6,739 buildings adding 220.2 hectares (2,202,099 m2) of green roofs to the city skyline since 2001; and Melbourne’s tree protection policy, which protects trees from removal and charges developers significant sums if they are removed. There’s also Berlin’s Landscape Programme and Biotope Area Factor (Biotop Flächenfaktor) which require new developments to integrate green space. Developed in the late 1980s, Berlin’s regulations have influenced several cities, including Malmo and Seattle.

However, improving urban nature in a city is not so simple as finding a good example and following the recipe. If a city government decides it wants to implement the measures Tokyo, Melbourne or Berlin have put in place, it may encounter staunch opposition. The media might convey such plans as anti-development or unnecessary. Indeed, certain stakeholders will rally against the new planning requirements before they are even made public. However, if a city government invests time to work with its community and stakeholders to tackle problems together, ideas like this may be well supported and they may even be proposed by citizens themselves.

Working together, city governments and communities can make rapid progress towards creating healthy, natural cities. Leveraging networks and partnerships with the private sector is considered important for governments. We need to value community partnerships with the same gravitas. Working together, we can achieve more than any individual effort for our cities. The timing of securing a natural future for our cities has never been more critical than now.

about the writer

Emily Maxwell

Emily Nobel Maxwell is dedicated to environmental justice and urban greening. She is Director of The Nature Conservancy’s NYC Program and Advisor to TNC’s North America Cities Network.

Emily Maxwell

In the United States, your life expectancy can be predicted by the zip code in which you live. While there are many factors at play, study after study shows that healthy people need healthy environments. To achieve an urban century in which all people, flora, and fauna survive and thrive, we must work in all cities and across all zip codes. We must treat nature in cities as a matter of justice—a basic human right of all people. And we must invest deeply in those communities that have been marginalized to help them protect their natural assets where they still exist.

The forces that denude landscapes and threaten biodiversity challenge all life, including and especially people. As climate change increases both the duration and intensity of heat waves, water supplies are being stressed, plants and trees are removed, and soils are compressed and paved over, exacerbating the impacts. More Americans die from heat waves than all other natural disasters combined, yet they receive relatively little public attention. In July of 1995, Chicago experienced a heat wave where 473 deaths were attributed to excessive heat. This summer (2018), heat waves killed 96 people in Tokyo, which recorded an all-time high of 106. Dozens of people were killed across the U.S. and in Canada—including 54 people in Montreal. As reported in the Guardian, “the majority were aged over 50, lived alone, and had underlying physical or mental health problems. None had air conditioning.”

Heat waves are projected to increase in length, frequency and intensity over the coming decades, and urban landscapes intensify their effects. The good news is that nature can help. Shade from tree canopies can lower surfaces’ peak temperature by 20–45°F (11–25°C), and increasing trees and vegetation can alsoimprove air quality, lower greenhouse gas emissions and enhance stormwater management and water quality.

But how do we ensure all people can access these benefits?

First, we must seek intersections between conservation, public health, and environmental justice— between those who advocate for the rights and dignity of nature and those who fight for the rights and dignity of people. And we must organize at those intersections for collective impact. We must look at the whole landscape, both physical and social. And we must reject the mythology that only certain people care about the environment.

After all, evidence shows that people who face the greatest environmental ills care deeply about the environment. To plan for a positive natural future, we must cultivate relationships with these natural allies, making clear and meaningful connections between social and ecological struggles. We need to recognize, listen to, understand, elevate, and amplify the voices and solutions of those who are on the front lines of ecological and social degradation. Ultimately, we have a duty to invite people to the table who we see are missing, then build bigger tables and join others’ tables.

Who is “we”? Of course, everyone has a role and responsibility in this but I’m focusing my recommendations first on big green organizations, like the one I work for. And as a U.S. resident, I’m writing from a U.S. perspective, though I’m keen to learn what my colleagues from other countries recommend.

Justice is about people and about places. If we invest in natural solutions in those neighborhoods that need them most, we can ensure not only a natural future for cities that protects and even restores biodiversity, but an equitable, resilient, and sustainable future as well.

about the writer

Colin Meurk

Dr Colin Meurk, ONZM, is an Associate at Manaaki Whenua, a NZ government research institute specialising in characterisation, understanding and sustainable use of terrestrial resources. He holds adjunct positions at Canterbury and Lincoln Universities. His interests are applied biogeography, ecological restoration and design, landscape dynamics, urban ecology, conservation biology, and citizen science.

Colin Meurk

I pondered the “one critical action” and know the forum will come up with many relevant things to do to make cities biodiverse and legible while supporting ecological integrity and natural character. I think many of us who were sentient beings through the 1980s and before, believed that there was a dawning if reluctant recognition of the fact that governing structures were fixated on single bottom lines. And Triple Bottom Line (TBL) was born and seen as the way forward. It was on corporate and governors’ lips but, by and large, no actual change in structure and representation took place.

Instead we have often well-meaning, intelligent, and experienced business minds still running the show—gate keepers who “don’t know that they don’t know” the ecological risks and opportunities they are continually overlooking. Somehow ecology is cast as special pleading whereas commerce, engineering, and a nod to culture are not? We recently had a visit from an inspirational Canadian speaker—Dr Enette Pauzé who coached us on mastery of leadership, partnership and stewardship, http://www.valuebasedpartnerships.com/about. The question of how governing bodies can be more inclusive (more TBL), understanding, and remedying inherent bias, was neatly unpacked and answered, but my question is how does one, from outside the tent, convince conventional governing structures in the first place to share their power with ecology, sociology, and cultural diversity? We have previously discussed the relative success of Landscape Architecture in gaining traction for urban design; and one can see how beautifully and innovatively crafted, animated depictions of some imagined landscape will appeal to governing bodies who don’t have the deep ecological insight to drill down to the functionality, sustainability, biogeography or sustainability of such designs.

So my action is to get governing bodies to open their eyes to opening the door to not only “ecology” (everyone knows what that is, right?) but to ecologists. Afterall, we all know about health, but we do seek medical opinion when we have a broken leg!

So my action is to get governing bodies to open their eyes to opening the door to not only “ecology” (everyone knows what that is, right?) but to ecologists. Afterall, we all know about health, but we do seek medical opinion when we have a broken leg!

The irony is that (holistic and projective) ecology is surely the key discipline required to save the planet and yet is seldom if ever represented in decision-making except as nice to have, green fluff (or wash) sprinkled like fairy dust after the “real decisions” have been made. The professional status of ecology needs urgently to be raised as capable of rational thought and often more acutely aware of inherent biases than many other professions. The consequence of this is that design and landscaping should always be informed by professional, experienced ecologists—not just by what people think they know about this complex topic.

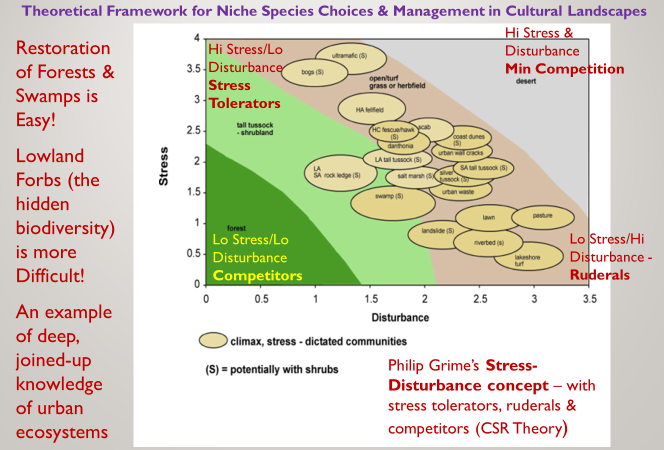

An example of necessary joined-up thinking is the importance of “urban wild” in bringing nature and people together even in constructed environments where the conventional tendency is to control and sanitise. A little-known fact is that Berlin (of all places) allows “weeds” to grow in footpath cracks. Like “forest bathing”, this should lead to a more relaxed and forgiving attitude, not just towards nature but to all such interdependencies—one might call it ecological literacy! And for control freaks there is always Joan Nassauer’s “messy ecosystems – tidy frames”.

To summarise: there have been decades of grass roots actions on the environment and there are many initiatives and quasi-polices spawned from this movement. But show me a Board or executive with an actual ecologist on it. We need more ecologically literate/informed governance, not just a vague notion that when “we” think we have an environmental problem we will know to come and ask.

No, we need the canaries in the mine before the disaster!

about the writer

Ragene Palma

Ragene Palma is a Filipino urbanist currently studying International Planning at the University of Westminster, London, as a Chevening scholar. Follow her work at littlemissurbanite.com.

Jean Palma

If there was one specific action to push cities for a positive natural future, it would be undertaking conscious urban planning and management that truly integrated development with the natural landscape and ecological systems—not compliance-based, not politically lopsided; just conscious.

While this is not a new approach, and while many cities around the world have made outstanding achievements towards truly sustainable planning (the Netherlands could boast of this), there would always be a different point of view from a developing country.

Cities in the Philippines have very varied levels of development, and it’s due to many reasons: island locations against landlocked areas, unequal distribution of national resources, metropolitan centrism, among many other factors. But one thing is common to our cities: we keep creating plans, yet we leave our resources unchecked, despite the knowledge that the natural environment is finite.

Take Metro Manila, for example. Sixteen cities and one municipality are growing with a 4.4 percent urbanization rate per year, congesting the already concrete-laden capital region, and further increasing the push-and-pull dynamic with provinces. Despite decades of using comprehensive planning to supposedly manage and sustain its growth, the poor implementation has even pushed the boundaries of the metro to create Mega Manila, intoxicating the agricultural fields and fishing grounds of its neighboring regions with sprawl, resettlement, and unmanaged development. While efforts such as designed cities and climate guidelines have entered the planning arena as attempts to make sense of the confused urban fabric and increasing climate impacts, the metro remains to be mismanaged as ever.

This manifests in everyday experiences in the cities. Metro Manila can hardly be called walkable or comfortable—it just shows how disoriented it is towards human-centered design; so what more for wildlife and the natural environment? If a common commuter can’t even bike across a few hundred meters without fearing for his or her life, and if going through the central business districts call for a face mask as protection against emissions, then how can we even create cities that are welcoming towards fauna? The Philippines is home to “two-thirds of the Earth’s biodiversity and 70% of the world’s plants and animal species due to its geographical isolation, diverse habitats, and high rates of endemism.”[1] And yet, we hardly drive cities to become inclusive towards nature.

The segregation of living things, which is apparent in how many of our cities are built, shows that there is a lack of consciousness and concern for the life around us. Our development is associated to a growing economy and more and more cars—malls pop up almost as fast as Starbucks and 7-11’s, and yet, our wildlife is shunned to cages, and we push back our forests and coastlines in exchange for “progress”.

A call for consciousness in urban management and planning is a call for professionals—environmental planners, architects, landscape architects, designers, and other urban leaders—to pay respect to nature. The how-to all of this of takes a variety of solutions, including conservation of green spaces, making open spaces permanent and multi-use and geared towards ecosystem services, and planners encouraging governments for more buy-backs in terms of property that could be transformed back for natural causes.

This also applies to already congested cities, even in the developmental setting. Some key actions that may be taken include re-integrating flora (and eventually fauna) into the pocket spaces of heavily cemented networks, re-establishing walking trails in the city that extend to rivers and metropolitan borders, and designs that integrate the built-up with the natural environments.

[1]USAID B+WISER Program (2017). https://www.usaid.gov/philippines/energy-and-environment/bwiser (Accessed 23 Nov 2018)

about the writer

Jennifer Rae Pierce

Jennifer Rae Pierce heads the Urban Biodiversity Hub’s Partnerships and Engagement team and is a steering committee member. She is a political ecologist and urban biodiversity planner. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver on the topic of engagement in urban biodiversity planning.

Jennifer Rae Pierce

What is a bioshed? The bioshed is all of those parts of nature that your city depends on, impacts, and stewards. It includes your city’s watershed, food sources, all the “away” places that waste goes, all the places where resources come from to the city, and all the landscapes that the city is in charge of, like parks, abandoned lots, playgrounds, private land, and development sites.

What is a bioshed party? It’s a fun and select gathering of people with diverse perspectives who come together to understand your city’s bioshed. The outcome of a bioshed party is a diagram of your city’s bioshed in the past, today, and in a happy future. It forms a directive for the city and its citizens to acknowledge its dependency on local and global landscapes, and to take responsibility for them.

Ingredients:

- A big, welcoming space

- Food and drinks

- Lots of huge sheets of paper and quality markers or other artistic elements

- Illustrators and facilitators

- Youth and elders

- Indigenous and traditional cultural leaders

- Community leaders of vulnerable or oppressed groups

- Technical experts in food, waste, industry, transportation, energy, construction

- Ecologists and natural resource experts (fishermen, forestry experts, etc.)

- Local government decision-makers and planners

Create visual outputs at each step:

For each step below, create an oversize poster together.

- Draw the bioshed of the past. Choose any time frame, but one suggestion is to start with the time period representing the childhood of the eldest person in the room. Include important natural elements from that time (animals, rivers, etc.)

- Draw the bioshed of today.

- Compare the two diagrams and list how we got from the past situation to today. What happened and how?

- Draw the bioshed of a happy future

- List the assets of your city today and celebrate what you have already done to move in the right direction

- List what you still need to do to get to the happy future scenario

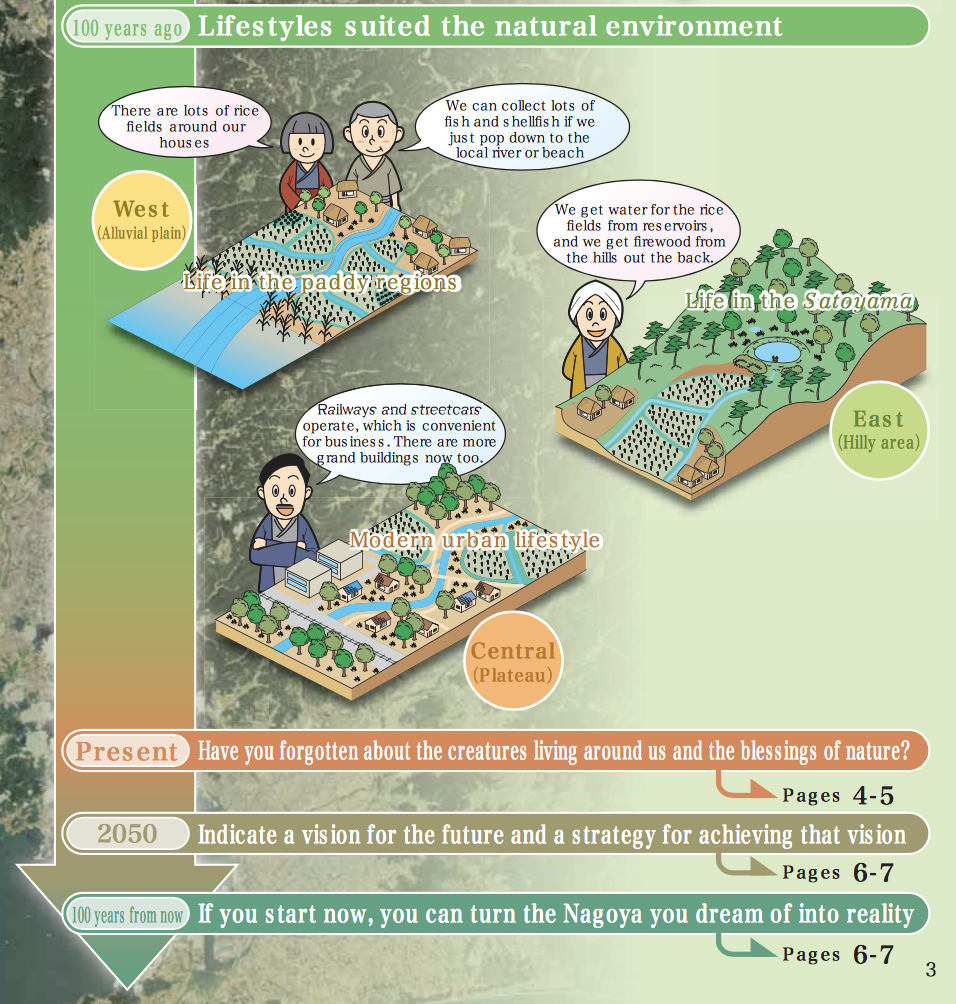

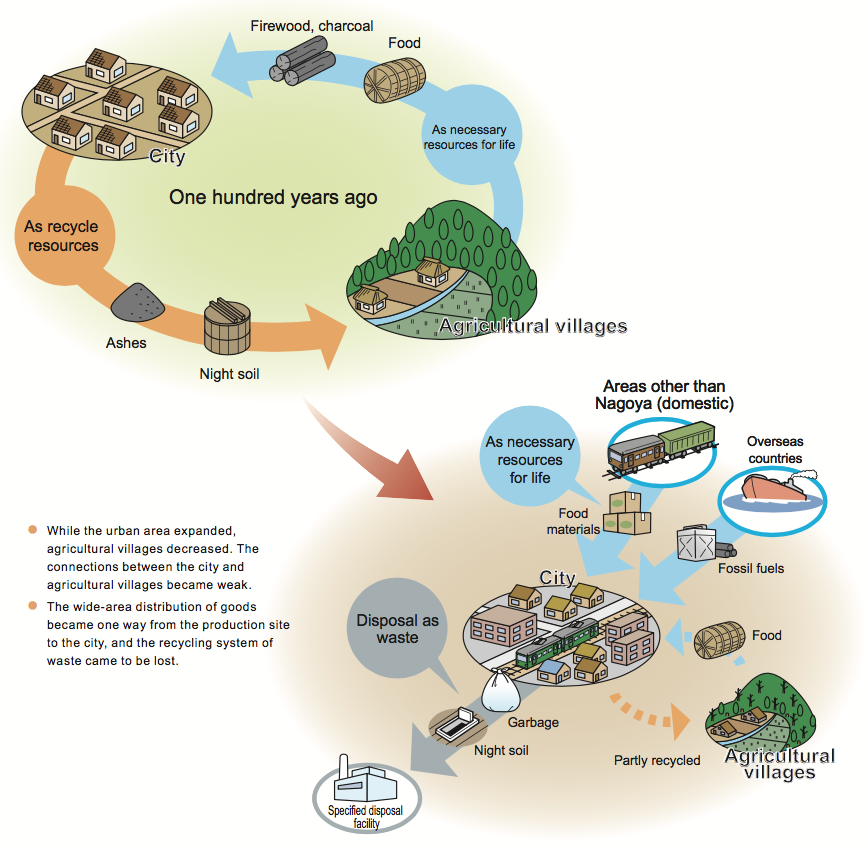

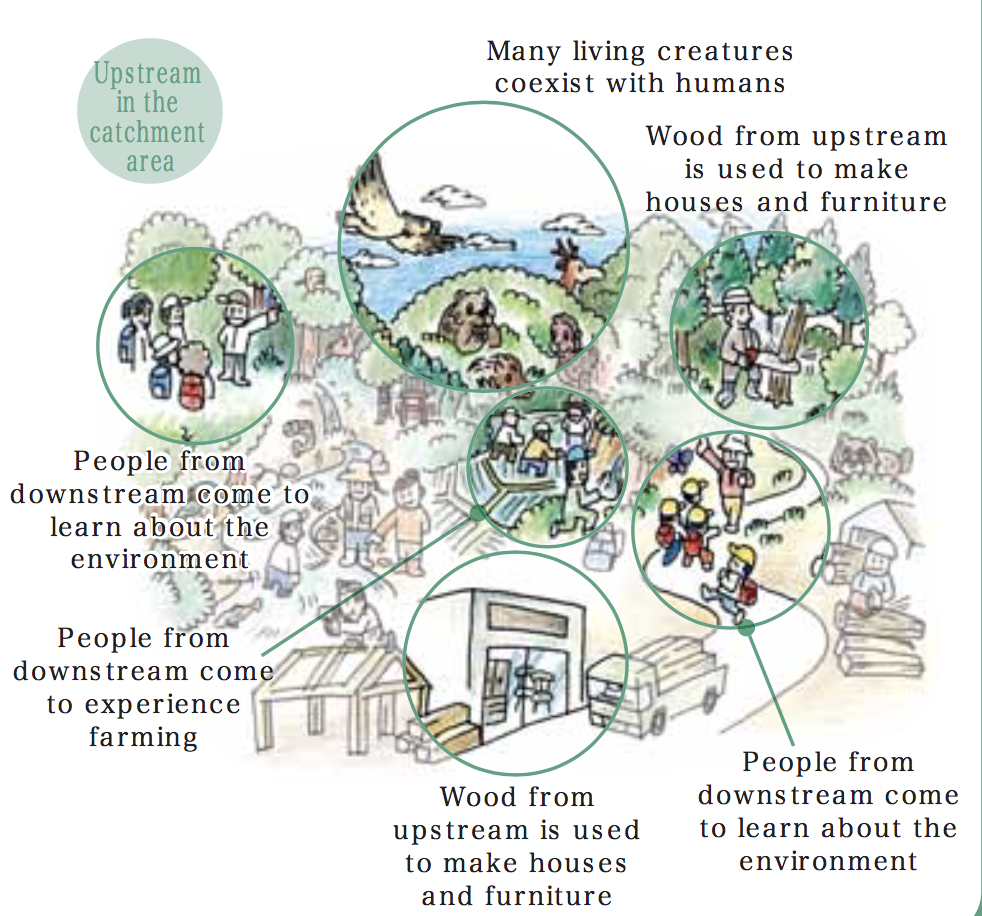

An example drawing for a connecting historical conditions to current day conditions from The 2050 Nagoya Strategy for Biodiversity, chapter 2. Produced by the City of Nagoya, (2012, p. 37)

Close with reflection and action: Set aside time for silent reflection on what participants can contribute. Call for volunteers to form a committee who will transform the resulting drawings into a pledge, which the city can host on its “Bioshed Party” web page where people can discuss and commit publicly to the pledge.

What is the impact? A bioshed party encourages participants to think differently about the role of cities in conserving nature. It illustrates a vision for your city in harmony with nature. In this way, it addresses the perceived lack of connection between our urban lives and nature. Through the three drawings, participants connect the experiences of generations of the past, today, and the future. The bioshed party demonstrates how all members of the community are part of a positive solution.

about the writer

Mary Rowe

Mary W. Rowe is an urbanist and civic entrepreneur. She currently lives in Toronto, Canada, the traditional territories of the Anishinabewaki, Huron-Wendat and Haudenosauneega Confederacy, and works with government, business and civil society organizations to strengthen the economic, social, cultural and environmental resilience of the city and its neighborhoods.

Mary Rowe

Diversity is the underpinning of every healthy ecosystem—natural and human. It ensures cross- pollination, adaptation, course correction, efficiency, productivity, and, often, unexpected beauty. This is as true of human-centred ones as it is of ones where human habitation does not dominate. The worlds’ most resilient citiesthe ones that have endured centuries—have an elegant connectivity that enables movement, exchange, solo and communal activities. Before the industrial revolution, the urban neighborhoods that formed up were dense and idiosyncratic, adapted to the landscape, and a range of amenities seemingly emerged “organically”, close at hand. These urban forms have evolved over time, mirroring the natural ecological world in which they reside, each teeming with endeavor.

Sadly, over the decades urban development patterns in North America predominantly followed an industrial path, preferring uniformity over uniqueness in pursuit of “economies of scale” and rapid production. The more organic, human-scale development created by craft and a local labour supply sourced within a few hours walk, was replaced by mechanized, mass production dependent on automobile travel. Contemporary metropolitan regions are left with huge swaths of monotony: tall towers surrounded by half empty parking lots and 4 lane roadways, or single family “estate” residences, with multi-car garages, adjacent to private golf courses.

“Sprawlation” is the daily context for millions of urban dwellers. These artificial forms no longer mirror the intricate interactions found in the natural ecosystems from which they sprang. Units are isolated, there are no corridors or patches even of biodiversity, and a generation of urban dwellers has been deprived of those tactile reminders of the natural roots of place.

Enlightened designers are making attempts to better mimic the natural patterns enabled by diversity in natural systems to guide their plans for parks, neighborhoods, transit systems. We need more efforts like this, reminders of what true urbanism actually looks like: an ecosystem. Connected, porous, rich with feedback loops and redundancies. But faux versions: where designs are artificially imposed, lacking in connections to the vernacular elements of neighborhoods and local people, instead “dropped into place”, defeat the purpose.

This can be more than depressing for ecological urbanists, because the bad patterns of development are locked in our economy, regulatory regimes, and cultural expectations of the middle class. And as with any significant phase transition, the system needs many more disruptors than a cadre of progressive planners, urban designers and architects can catalyze.

To have any real impact on re-surfacing the natural into all aspects of our shared urban life, action must start at the most basic unit: the household. Here is my suggestion for one simple, elegant action that households should undertake, to symbolize, and concretize, a collective commitment for a positive natural future

Municipal governments should strictly limit the zoning approvals for new single-family homes to designated intensification areas, and make easy the approval of multi-unit residential development in existing built-up areas (“infill”) where services exist (and may need to be upgraded).

In addition, provincial (state) governments should levy a modest “heritage occupancy tax” on all dwellings: residential and commercial, to seed a revolving restoration fund to invest in ecological restoration and new forms of green infrastructure. (For instance, in Toronto where I currently reside, a meagre1% percent of assessed property tax would generate about $40 million dollars annually). To create more incentives for recognition and behavior change, households could be offered various ways to exempt themselves from the levy (e.g. installing alternate energy sources, use meters etc.). And the levy could be graduated to favour denser neighborhoods over sprawling ones.

This levy would acknowledge our fundamental, inherent connection to the resources, topography and history of where we live, and be a constant reminder of the natural assets upon which we depend, and their need for replenishment. Together with courageous zoning leadership from municipalities, it will curtail sprawlation.

I have only recently returned to live in Toronto, having spent a decade working in the US. Here, it is common practice to begin every public event with a land acknowledgement of whose territorial lands we occupy. It has become for me a powerful signal of our temporariness. Taking steps to more explicitly monetize the true costs of our occupancy would empower our cities to better plan for a positive, natural future.

about the writer

Luis Sandoval

Luis Sandoval is a researcher and professor at Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica. His research focuses on urban ecology, animal communication, and behavior and natural history of birds.

Luis Sandoval

Also it will provide knowledge to help decrease the impact of cities on natural habitats and guidance to recover some of the species that are not present now, but which were present before. It will facilitate an evaluation of whether the effort in the protection, conservation, and restoration of the natural habitats, due to management or connection between remain patches of natural vegetation, has a positive effect on species conservation.

Thank you all for your insightfull presentations & opinions! I have been encouraged to keep on persuing my mission to implement a Go-Greener Action Plan in our Municipal area, and thanks I am encouraged to continue by you, despite the opposition, reluctance to change & adaption of the oldd laws & leaders, set in their ways! I suggested we Train our Youth to understand true green living, so they may be able to implement these aspects when they need to take charge! may we train them well, to be enabled, equiped & excited to take the baton from us, and run with it = on Green Fuel, common logic & resourcefullness! that is my heart’s desire

A city is situated in an area, an eco-region or biogeographical region with a certain bioclimate. The climate is not the same in the city. Yet some plants and animals know how to adapt. The concept of geobotany by Alexander von Humboldt, later picked up as plant sociology by Josias Braun-Blanquet with many followers, is indispensable to smartly improve the biodiversity of a city. If you do not have the insight of a plant sociologist then chances are you will miss the shelf, as many landscape ecologists, for example. In a city in a garden in a park, people plant what they want. It is a cultural garden. These are often exotic plants that only remain alive because they have been planted. They do not spread spontaneously. You have to replant them each time. There is no vegetation here. It is simply a collection of planted plants that can not sustain themselves permanently. Often they also need extra food and water. In a plant-sociological garden or natural garden, the plants are not arranged by the people, but organize themselves. This also happens in nature. Spatial planning by people is based on the principle of the drawing board with man as center. However, the wild plants look for themselves where they grow. That is much more sustainable and the insects are also much better adapted because they are local indigenous actors. Between the paving stones, in the verges, on the roofs, the walls, fallow fields everywhere wild plants can grow. By many people who have no understanding such wild indigenous plants are easily called weeds. Clean people want a clean city so the weeds must be combated. No, not exactly. If you understand how these wild plants like to behave and which patterns they can spontaneously form, then you do not have to plant parcels, but you can let nature take its course much more spontaneously. It is important to keep out invasive exotic species as much as possible. Invasive exotics come to the city because people travel the whole world and thus help to spread a huge number of species from remote regions that could never have come to the city on their own.

I was very pleased with the example that Yvonne Lynch gave from Tokyo. Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Nature Conservation Ordinance. This refers to the Guidelines for Selecting Native Species for Greening report. Excellent! I did not know it. Is an eye-opener. I am so happy that in Tokyo people have good insights that we can learn a lot from. By the way, I found all contributions very useful and good food to think about the complex matter. Nature, but also the city can be viewed in countless ways. These kinds of forums are very important to understand each other’s disciplines. It is an example of a multidisciplinary approach.

Certain cities are facing water shortages. The one specific action these cities should take is the one that ensures an adequate supply of water for both human and non-human (e.g., riparian wildlife or urban forestry) uses. It might mean strict water rationing, building desalination or tertiary water treatment facilities, or enacting slow-growth initiatives.

What a fantastic group of essays. It was an honor to be a part of it, and I learned a huge amount from the various perspectives — this tapestry of ecological urbanism.

Jean Palma’s comments really will sit with me for some time to come: “If a common commuter can’t even bike across a few hundred meters without fearing for his or her life, and if going through the central business districts call for a face mask as protection against emissions, then how can we even create cities that are welcoming towards fauna?”