We scan the neighborhood for a dry place to pitch our tent, a daily part of our Asia-to-Europe walk.

No one is around to ask for help; it’s a summer afternoon, and people are resting in their homes. The rain encourages them to stay inside.

We find an old school, abandoned for years, it seems. The walls and roof are intact, but shattered glass from the long-forgotten windows is splayed all over the floor, classroom doors are missing, toilet bowls have been yanked out of bathrooms and dripping rain water falls into puddles pooled in the hallways. We use a few tree branches to sweep away the dust in a small corner that will be our home for the night, the only option we have today. We stare at the red graffiti scribbled on white walls and names of kids etched into the left-behind chalkboards.

A short while later, a boy about 12-years-old sporting a hooded sweatshirt strolls through the school hallway. We hear the rap music from his phone before we see him. He glances into the classroom where we are camping. I wave. He nods.

A few minutes later, two teenage girls pass through the same hallway. We hear them chatting before they reach the classroom. We wave and say hello in Greek. They return the greeting, and keep strolling through the school. We hear them giggle as their footsteps fade on the dirty concrete floor.

It doesn’t take long before another group of pre-teens and teens finds us. There are few young people in this village, and word has spread that tourists are sleeping in the old school.

A group of five young women from 10 to 17 years old enter the classroom. The boy with the sweatshirt and his friend will join the group a bit later.

“Are you okay? Do you need anything?” asks one of the older teens in excellent English.

“Thank you for asking. Yes, we are fine. It’s been raining all day, and this was the only dry place we could find to sleep in tonight. Is it okay that we sleep here?” I say, half-asking and half-telling. Our tent is already up, and unless the police come and tell us to leave, we know we’re here until tomorrow’s first light.

“It’s okay that you stay here. It will rain during the night,” she says. “The rain has made all the park benches wet, so we hang out in the school.”

The school, which was used by their parents and grandparents, has been closed for years, her whole life, at least, she tells us. The village children are bused to schools in other towns, but the ruined building we are all gathered in still serves a purpose, a sad one at that.

“It’s better to hang out here than to stay inside our houses all day,” another young lady says, shrugging her shoulders at the normalcy of being in this run-down place. “There’s nowhere else for us to go.”

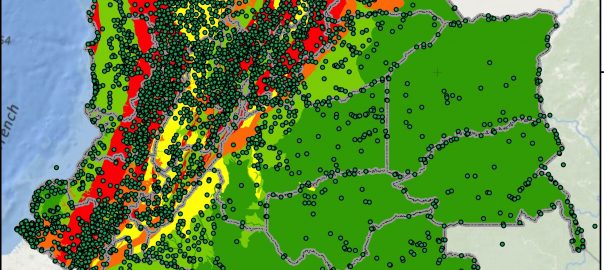

This “nowhere else to go and nothing else to do” concept follows us through our last stretch of Turkey, into Greece and deep into the Balkans. It shows up as abandoned buildings used by children and young people who have no parks to play in or when their parks are not well maintained. It also shows up in adult circles in the form of bars, cafes, and betting places where men stay for hours sipping their beverage of choice and hope lady luck puts a bit of extra cash in their pockets.

The “regular” tourist passing through these regions by car or bus may never notice these things. It seems like a normal thing that people sip coffee or rakija, ouzo, or other distilled liquors some part of the day. It is waved off as part of the country’s culture. And the falling apart facades fade into the wide landscape where wheat fields have been cut and rolls of hay are waiting for a tractor to haul them into a farmhouse.

To us, walkers who have traveled about 13,000 kilometers by foot over more than 2.5 years at a snail’s pace of three kilometers an hour, the increasingly noticeable presence of these overlooked village, town and city aspects take on a different meaning. They are signs of depressed economies, and resonate with a sense of helplessness and hopelessness.

Where the kids go

While many of the places we walk through have manicured gardens, playgrounds where kids can climb and jump, and nice parks and cafes to sit in, there are many other places that catch us off guard.

In the mid-size town of Burrell, Albania, for instance, we take a rest on the steps of what by all counts looks to be an abandoned apartment building, something built in the 1960s when square functionality was the design trend among architects. Its better days are far behind it, and the chipped paint, broken glass and gray lobby vestibule make us think the building has been out of use for years, maybe decades.

But, then we hear it. The sound of young people talking, and the echo of billiard balls colliding. They are confusing sounds in the context of decay.

Some of the children, most of them about 10-12 years old, find us and, with bright-eyed curiosity, quiz us about our walking journey. When they run out questions, they tell us they are going back inside to play.

We walk off as the crack of a new game of billiards begins.

A few weeks later, in Podhum, Bosnia and Herzegovina, memories of our night in the old Greek school return.

Pouring rain forces us to stay in a dry but creepy auditorium, the small basement room of a school that seems to still be in use and where classes may start in the coming days. The gate door barely hangs on its hinges. Some of the heart symbol graffiti about who loves who dates back to the mid-1980s, and we speculate that the bullet shells lodged into the walls are reminders of the war that swept through the former Yugoslavian countries in the 1990s.

The room is littered with water bottles, soda and energy drink cans, and potato chip packages. The pile of cigarette butts in one corner make us think young people come here to hide their smoking habits from their parents, or, like the young people in the Greek village we met, they have nowhere else to go, especially on cold and rainy nights in this rural, hilly area. A distant thought clouds over: could this place be a stopover point for refugees and migrants escaping from Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan and North Africa? It’s a very real possibility as parts of our European walk parallels theirs.

The number of abandoned buildings we see during this leg of our journey these last several months raises bigger questions. What’s really going on here in this part of the world is one of the things we keep asking ourselves.

Where the men go

Sometimes the answer is right in front of us, sitting at one of the many bars and cafes we can’t help but run into.

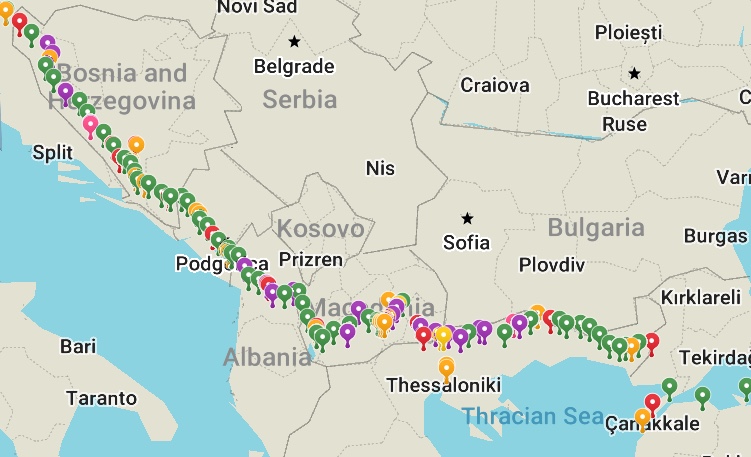

Very frequently, the bars and cafes we have passed from Çanakkale, Turkey to Bihac, Bosnia and Herzegovina are filled with an intergenerational mix of men. The old men are usually farmers or pensioners living on a budget; the young men typically in their 20s are mostly unemployed. They all drink the same thing: Coffee, beer, and raki/rakija (the name and spelling of this hard liquor changes as we move through each country, but it’s always present).

“I lived in Germany for a while, and made a lot of money. But, I was sent back here, and now I have nothing. No savings, no job, nothing,” an Albanian 20-something-year-old tells us during another rainy afternoon when we are trapped inside a smoky bar where Latin American Spanish music is the choice beat from their YouTube TV connection. “What am I going to do? There’s no work in this country. I come here (to this bar) every day. I’m here all day. These guys are like my family.”

We glance around the room and have mixed feelings about these men. The resignation about their lot in life is evident on their faces. But, we are not ones who dole out pity.

“Why don’t you create work? There must be something that can create a better economic situation here,” I say, almost pleading.

The young man tells us what many others tell us in every country we walk through: The government doesn’t work; the politicians are corrupt, and people don’t have any chance to make money. He says the only job he may get is cutting trees deep in the forest, and that’s not appealing work. He wants to go back to Germany and get a job translating Albanian, German and English, but he needs certificates he can’t afford unless he takes the work as a lumberjack.

It is a cycle that feeds the helpless and hopelessness bubbling just below the surface, and shadows the easy-going conversations we have in places where hospitality to visitors is a underlining principle.

The increasing number of sport betting places, usually attached to the bar and cafes where men hang out, doesn’t help matters.

“Ninety-nine percent of the men watching this match have money on the game,” observes our host in Bitola, one of Macedonia’s few cities, swirling his finger around 360 degrees pointing to the World Cup soccer match being broadcasted on every television in every café and restaurant along the main pedestrian street. “Everyone says they have no money. But there is always money for coffee, alcohol, cigarettes, and a bet on the game.”

Our host in Thessaloniki, a big Greek city off of our walking route that we visited for a few days, mentions something similar.

In Greece, a country that was hard hit in the last recession and whose people are struggling with European Union imposed economic austerity measures and high unemployment rates, betting places recently became legal, and they are popping up everywhere, our host explains. Often during our walk, we notice a handful of betting places just a few meters away from each other on the same street, and sometimes they are near money transfer shops where people receive cash from relatives living and working abroad.

“It’s another way to prey on the poor. People earn little money, and they think if they win a few Euros, that will help them out of their hole. But, they never win,” he says, shaking his head at the illogical behavior capitalism fuels.

This is the push and pull we feel as we walk.

When we have the good fortune to find people who speak enough English and are willing to have more thoughtful conversations with us about their lives and dreams, they tell us what they want. They want a bigger house, a car (or another better, higher-end car), another television, nicer clothes, and, yes, better education and life opportunities for their children, who they hope will make enough money to take care of them when they are old. The story is the same almost everywhere we go, from Asia to Europe.

But, who really has access and resources to turn this wishful thinking into reality? How viable is this line of thinking in the near-term? And further into the future.

Will the children who listen to rap music or play billiards in destroyed buildings be the ones to turn their local economies around? Will the young guy who hangs his hope on getting out of wherever he lives and earning paycheck in another country come back and build something the generations after him will benefit from? Will governments create initiatives to help their people living both in cities and rural areas do more than survive?

We walk on mulling over these questions and inventing philosophical possibilities for the people we meet along the way.

Signs of depressed urban and rural economies blur our vision. It’s a long road ahead for all of us, for the people we meet who want something more than they have and for us the walkers who have learned to live with less. One step at a time often feels too slow for such a big undertaking.

Jennifer Baljko

Bangkok to Barcelona

Add a Comment

Join our conversation