Where once Henry Walter Bates saw a vibrant and lush paradise, the very water Bates once leisurely enjoyed in his favorite spot in Belém is now overrun with sewage and disease. But the fight for a better city is not over…not if grassroots mobilization has anything to say about it.

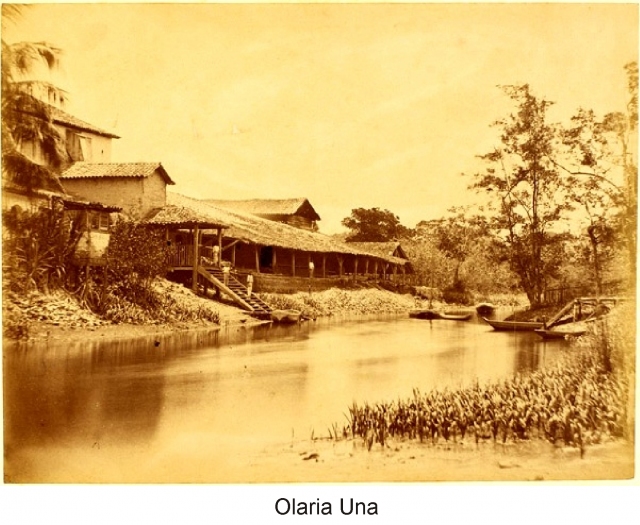

More than a century before this, though, Belém and the Una Basin were already world renowned for the region’s natural beauty. In the late 19th century, the famous English naturalist Henry Walter Bates used to walk through the várzea forests of the Una Basin and sail through the streams that connected the Guajará Bay to the vicinity of what was then downtown Belém. Bates described the Una Basin as his “favorite spot” and a “paradise for naturalists” (Bates 1944:83)—which is a good illustration of the historical perception of the Amazon region as “God’s Paradise” (Brondízio 2016). The contemporary urban imagery tells a distinct story, however. The status of paradise has changed as the Una Basin endured the impacts of what Belém’s policy-makers envisioned as modernization from the mid-20thcentury onward. In the mindset of the political leadership of this period, for macro-drainage projects to be considered modern when building basic sanitation and water treatment systems, the constructors used to rectify and concrete part of the streams connected to the Guajará Bay, which likely affected the permeable capacity of the soil. This standard was applied, for example, to the Docks region, a commercial hub at the time (see Figures 1 and 2).

Although development programs change over time and across landscapes, parallels exist between the Una Project, blueprints designed for the Amazonian forest, and the construction pictured in Figure 1 almost a century earlier. In the name of progress, modernity, and ultimately development, both nationally and internationally funded urbanization projects attracted a massive influx of migrants to Belém. With this influx of migrants, the banks of the Una River and its tributaries became dotted with various factories producing paper, vegetable oil, screws, packaging, and soap. Industrialization unfolded in tandem with the growing population density, resulting in increasing environmental degradation of the Una Basin.

It didn’t help matters that the old myth that Amazonian waters can absorb pollution, which rather seemed to be an assurance for people and reinforced cultural assumptions that the waters were by nature regenerative despite growing mistreatment of the environment. This myth was a powerful one—and arguably it still affects the region today (Brondízio 2016). It is not uncommon to find old residents in the Una Basin who recall the catastrophic image of fish floating on the surface of the Una River and other streams. It was, however, only the beginning of dealing with issues caused by the water. The strategy of concreting and rectifying the channel system to drain water was replicated in the Una Basin, albeit with minimal success in managing waste and hydrological resources (see, for example, the confluence of two canals in Figure 3).

The environmental damage to the rivers and the marginalization of impoverished Amazonians are complementary aspects in terms of water and land use of urban space in Belém. Informal settlements have either replaced or surrounded the factories and large constructions that occupied the banks and tributaries of the Una Basin. Over fifty percent of the individuals living in Belém reside in these settlements officially named as “subnormal agglomerations”, which are mostly located around lowland areas and close to the water. The lack of basic sanitation that affects about 90% of Belém’s population, combined with even just one season of heavy rainfall, easily exposes these disadvantaged neighborhoods and over half million people to the risk of flooding and the hazards associated with it (Mansur et al. 2016). In the end, while the “clean” water may wash away part of the sanitary waste, the contaminated water may also invade people’s homes in recurrent and often unpredictable flooding events. This situation happens every year, for example, in the location depicted in Figure 3, which is a longstanding front of fight and resistance for the better management of the channel system of the Una Basin. (Compare Figures 4 and 5.)

After years of mobilization, in 2013, local citizens managed to obtain a report from the Commission for the Defense of Human and Consumer Rights of the State House of Representatives (ALEPA—Assembléia Legislativa do Estado do Pará in Portuguese; see Comissão de Representação da Bacia do Una, 2013). The state legislators participating in this Commission investigated and confirmed that the Stations for Sewage Treatment (ETE, Estação de Tratamento de Esgoto in Portuguese) planned for the area had not been built (Pará 2006: 21).

Consequently, the sanitary waste continued to be discharged, without any treatment, into the channels of the Una Basin and then released at Guajará Bay afterward. In a new context and era, we can confirm Eduardo Brondízio’s assessment, published at The Nature of Cities, that the myth of Amazonian waters being capable of absorbing and diluting all kinds of waste persists, insofar as it has been used to bolster governmental arguments for not dealing with the problem of sanitary sewage in cities like Belém (Brondízio, 2016).

Building and reshaping the “Gray Hell”: The mix of gray(ish) concrete, green but harmful vegetation, and brown-muddy water

The context outlined so far seems to describe a metropolis where public investment in basic sanitation has been absent. Unfortunately, this is not the case, especially when referring to the Una Basin. The Una Project cost, after all, over 300 million U.S. dollars. The IDB and the local government allocated these funds to improve roads, water, sewage, and drainage, transforming the urban landscape and the livelihood of its inhabitants.

On the books, the Una Project presents outstanding numbers regarding its accomplishments. A report by the Sewage Company of Pará (COSANPA, Companhia de Saneamento do Pará in Portuguese) lists that the Una Project built 25,731 individual septic tanks, 91 collective cesspits, 307 kilometers of sewerage network, 2,164 inspection wells, 3,887 cleaning terminals, and a drying bed of septic tanks (Pará 2006:11). In reality, however, the Una Project actually created a mosaic of gray, concreted canals, green weeds plaguing the spots without maintenance, and brown-muddy water that invades many houses in the region, shaping distinct experiences relating to sanitation and water among the residents.

Simply put, when asphalt arrived and floods ceased in some areas, many other areas remained without paved roads, sewage treatment, and still experienced flooding events. This meant that the population was forced to adapt to these mixed results accordingly.

For example, the two most significant shortcomings of the Una Project were that it excluded entire areas within the Una Basin from the construction. Also, the Una Project left several areas without micro-drainage structure that should have been built in parallel to the channel system. Controversy remains about the reasons for this exclusion.

This micro-drainage structure should include paving and surface drainage at the street level, as well as curbs, sluice gates, and manholes to handle the water coming from households and the rain. Vila Freitas, which is located on the banks of the Galo Channel, has long experienced flooding due to the absence of micro-drainage (see Figures 8 and 9).

The adherence to the system of urban governance established to implement the Una Project has resulted in varying degrees of success. That is, some progress has been made, but at the expense of having excluded more than half of the more than 100,000 families residing in the Una Basin from reaping the benefits of these infrastructure developments. It further highlights how crucial it is to work from a planning perspective that understands the interconnectedness of social and spatial distribution of infrastructure, such as in the case of macro- and micro-drainage issues. This is what we have found to be the case in the Una Project of development, the limitations that stemmed from it, and the persistent segregation of Belém (Brondízio 2016).

Indeed, complications with this project continued even after it arguably came to an end. When the Una Project was officially closed and the disbursement contract with IDB was terminated, the Municipal Government of Belém received lots of different types of equipment—machinery, and vehicles from the State Government estimated at R$ 21,977,619.75 (Pará 2005)—which exceeded 52 million USD circa 2005, corresponding roughly to 66 million USD in 2018. The IDB facilitated the purchase of this proper apparatus for the maintenance of the Una Basin channel system to ensure the sustainability of a project of this magnitude. As an institutional innovation for the time, there was an interest of the financing organization in establishing a sustainable governance system of the Una Basin.

Linking global to local interests, representatives from the IDB and various governmental agencies cooperatively drafted and proposed the manual of operations for the maintenance plan of the Una Basin. Yet, it is not known for certain the whereabouts of some items of this equipment, compromising the already insufficient capacity to maintain the existing macro-drainage structure. Such factors ultimately motivated the resignation of then Secretary of Sanitation, Luiz Otávio Mota Pereira, amid a rupture with the mayor. Much later, in 2013, the City Council of Belém launched an official investigation to determine what happened to the equipment, machinery, and vehicles of the Una Basin maintenance plan. The results of this investigation remain inconclusive nonetheless (Belém 2015).

Toward the mobilization of legal actors by FMPBU: Urban problems as a matter of environmental and social justice

The abbreviation FMPBU stands for Front of the Aggrieved Residents of the Una Basin (Frente dos Moradores Prejudicados da Bacia do Una in Portuguese). It was created in 2011, when aggrieved citizens circulated a communiqué denouncing the conditions of the Una Basin to the participants of a public demonstration carried out by the Brazilian Bar Association. Fearing retaliation from local authorities, members of FMPBU did not feel safe to list their names in that document, which highlighted the obstacles to mobilization in the young, still-fragile democracy in Brazil.

In 2013, FMPBU consolidated itself as an urban, grassroots movement during the demonstrations of what became known in Brazil as the “Journeys of June” (Jornadas de Junho in Portuguese). The protests occurred in several Brazilian cities and addressed several matters from both federal and local level political agendas. In Belém, urban infrastructure was a key point raised within this context. FMPBU members thus attempted to take advantage of the atmosphere of political and cultural effervescence by distributing that same communiqué document from 2011. Simply put, pamphleting was another way FMBU had devised to hold public officials accountable for the growing problems and raise awareness among Belém’s inhabitants of flooding being a public policy issue besides being an environmental phenomenon. After all, the media and political discourses often converge when using environmental rhetoric and blaming the population for clogging the canals with garbage as fundamental causes of flooding, overlooking infrastructural problems. Most importantly, the document called attention to the recent role taken by legal actors as mediators of the Una Basin case.

The aggrieved citizens, to be sure, were not satisfied with how political forces were managing the polluted waters flooding people’s homes. They continued to mobilize, concentrating their efforts on Belém’s legal arena next. After successive complaints, in 2008, the State Prosecutor’s Office finally filed an environmental class action suit—Brazil’s Ação Civil Pública. The defendants of this lawsuit were the State of Pará, the Municipality of Belém, and COSANPA, which are responsible for maintaining and finalizing the constructions of the Una Project.

Despite this step forward, the class action suit progressed slowly, with the presiding judge only beginning to take significant steps to move the case forward in 2013 after pressure from the National Council of Justice—nearly five years after the suit was filed. An additional setback was that when it came time to negotiate the contents of a legal agreement between the parties of the lawsuit. The state prosecutors, defendants, and the judge discussed the terms of and plans for this agreement without the inputs from grassroots movements’ leaders or any of the individual citizens affected by the floods within the Una Basin. Rather, while those players were meeting in the room where the judicial hearing was taking place, members of the movement and other citizens were awaiting their fate outside.

After 2013, the steps needing to be taken in compliance with the agreement above were suspended. The municipality claims that it has negotiated resources with the IDB to comply with the terms agreed upon in court, but obtaining these resources raises uncertainty as to whether this is a matter of more money or better governance to ensure the maintenance of the Una channel system. Former managers of Project Una have already stated that this amount is not enough to do the necessary revitalization process, not to mention the pending issues that have yet to be built. Moreover, once the funding from IDB is disbursed, residents of the Una Basin are concerned that these resources might be allocated to finish other macro-drainage projects in the city, e.g., the Estrada Nova Basin, and not to improve the situation of the Una Basin.

Through the length of the legal battle, the social uprisings, and political clashes, the Una Basin continues to endure consecutive years of flooding after its so-called completion. The environmental degradation and loss of quality of life for residence, in turn, raise doubt about the capacity to implement and enforce new urban policies in the Brazilian Amazon. Additionally, the management of the water and sewage system in Belém, in general, and the Una Basin, in particular, remains precarious with the population facing unpredictable and frequent flooding events. Let us not forget the role the Inter-American Development Bank played in this. The results of the Una Project question whether such international forces by a multilateral bank are capable of spurring best management practices aimed at sustainability or if this model can ever really improve the path-dependent systems that run these cities and continue to perpetuate inequalities. Belém thus reveals a complex political ecology of flooding with an interconnected mosaic of players and institutions at various levels of governance from both global and local scales, all of which have been called into and have shown limited capacity of action.

Where once Henry Walter Bates saw and wrote of a vibrant and lush paradise (see Figure 11), the very water Bates once leisurely enjoyed in his favorite spot in the city is now overrun with sewage and disease. What remains today is a complex social-ecological landscape, where flooded and eroded urban landscapes strain the quality of life and livelihood of impoverished and increasingly stratified social classes. To conclude, we hasten to say that this does not mean that the fight for a better city is over; well, at least if it depends on grassroots mobilization. Ten years after Una’s class action suit was filed, the state prosecutors called for a public hearing to discuss the pending issues of the Una Project. This hearing is going to take place in December 2018, and yet again, it is a direct result of persistent mobilization by the members of FMPBU.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Eduardo Brondízio for his comments on early drafts of this essay and the support of the Center for the Analysis of Social-Ecological Landscapes (CASEL) at Indiana University-Bloomington. We are also indebted to the members of FMPBU, the Assisting Program to Urban Reform and the Research Program on Urban Policy and Social Movements in the Globalized Amazon of the Graduate Program of the Faculty of Social Service at the Federal University of Pará (PARU and GPPUMA at UFPA). Special thanks to Andressa V. Mansur for her insights on this topic and her friendship that brought the authors of this essay together.

José Alexandre de Jesus Costa, Vitor Martins Dias, and Pedro Paulo de Miranda Araújo Soares

Belém, Bloomington, and Belém

* The authors have been listed in alphabetical order based on last name. They have equally contributed to the essay.

Resources

Bates, Henry Walter. O naturalista no Rio Amazonas. São Paulo: Brasiliana, 1944.

Belém. Câmara Municipal. Relatório Final da Comissão Palramentar de Inquérito com o objetivo de investigar indícios de irregularidades na transferência, para empresas da iniciativa privada, de veículos e equipamentos doados pelo Governo do Estado do Pará ao Município de Belém. Diário Oficial da Câmara, Belém, 15, 16, 17, 18 e 19 dez. 2014

Brondízio, Eduardo S. The Elephant in the Room: Amazonian Cities Deserve More Attention in Climate Change and Sustainability Discussions. The Nature of Cities, 2016. Available on: https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2016/02/02/the-elephant-in-the-room-amazonian-cities-deserve-more-attention-in-climate-change-and-sustainability-discussions/. Accessed on 08/02/2018.

Comissão de Representação da Bacia do Una. Assembleia Legislativa do Pará. Relatório Final. Belém, 2013.

Costa, Marco Aurélio, Isadora Tami Lemos (Orgs.). 40 Anos de Regiões Metropolitanas no Brasil, IPEA, 2013.

FMPBU. O que é a Frente dos Moradores Prejudicados da Bacia do Una? Frente dos Moradores Prejudicados da Bacia do Una, 2013. Disponível em http://frentebaciadouna.blogspot.com/2013/. Accessed on 08/02/2018.

IBGE, Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). 2011. Censo Demográfico 2010 – Aglomerados Subnormais: Informações Territoriais. Censo Demográfico Rio de Janeiro, available at: http://bit.ly/2mhWy4g.

Mansur, Andressa V., Eduardo S. Brondízio, Samapriya Roy, Scott Hetrick, Nathan D. Vogt, and Alice Newton. An Assessment of Urban Vulnerability in the Amazon Delta and Estuary: A Multi-Criterion Index of Flood Exposure, Socio-Economic Conditions and Infrastructure. Sustainability Science 11(4): 625-643, 2016.

Pará (Estado). Companhia de Saneamento do Estado do Pará. Ata de reunião para transferência de equipamentos para a Prefeitura Muncipal de Belém, conforme previsto na cláusula 6.05 dos contratos de empréstimo nº 649/OC-BR e nº 869/SF-BR firmados entre o Estado do Pará, mutuário final e o BID – Banco Interamericano de Desenvolvimento, órgão financiador,realizada em 02 de janeiro de 2005. p. 01-05.

dos Santos, Flávio Augusto Altieri, and Edson José Paulino da Rocha. Alagamento e Inundação em Áreas Urbanas. Estudo de Caso: Cidade de Belém. Revista GeoAmazônia 2(1): 33-55, 2014.

Vasquez, Pedro. Mestres da fotografia no Brasil: Coleção Gilberto Ferrez. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, 1995.

about the writer

Vitor Martins Dias

Ph.D. Student in Sociology at Indiana University-Bloomington. Affiliated Researcher at the Center for the Analysis of Social-Ecological Landscapes (CASEL, Indiana University-Bloomington), and Research Fellow at the Milt and Judi Stewart Center on the Global Legal Profession (Indiana University Maurer School of Law

about the writer

Pedro Paulo de Miranda Araújo Soares

PNPD/CAPES Scholar and Visiting Professor at Federal University of Pará (UFPA, Brazil). Member of the Assisting Program to Urban Reform (PARU) and the Research Program on Urban Policy and Social Movements in the Globalized Amazon (GPPUMA) of the Graduate Program in Social Work at the Federal University of Pará (PPGSS-UFPA).

Leave a Reply