As I have worked my entire career in the arena of metropolitan greenspace planning, I can safely say that now more than ever, people are working together across communities and regions to protect, enhance, and restore our natural and cultural landscapes within cities. For evidence of this groundswell of support, look no further than the National Forum on Landscape Conservation that took place at the National Conservation Training Center in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, USA on 7-8 November 2017. The event, sponsored by the Network for Landscape Conservation (the Network), brought together 200 leading landscape conservation practitioners from the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The Forumprovided an opportunity to share lessons learned, discuss ongoing challenges, and explore pathways forward to advance the practice of landscape conservation.

The Network has just released a report entitled Pathways Forward: Progress and Priorities in Landscape Conservation, which captures the insights of the Forum attendees, including the key finding that community-grounded, highly collaborative approaches to landscape conservation are on the rise. Perhaps when you see the term “landscape conservation”, you do not automatically think of the nature of cities. But now more than ever, I believe that landscape conservation is an essential framework for creating resilient, sustainable, livable, and just cities.

The Network report makes this compelling case:

“We know that healthy, connected natural landscapes are essential—for clean water, healthy ecosystems, cultural heritage, vibrant communities and economies, climate resilience, climate mitigation, flood and fire control, outdoor recreation, and local sense of place. And yet our approaches to these critical issues are too often piecemeal, scattered, isolated, and incomplete…Landscape conservation is about bridging divisions. It brings people together across geographies, jurisdictions, sectors, and cultures to re-weave fragmented landscapes and safeguard the ecological, cultural, and economic benefits they provide. This collaborative practice embraces the complexity of working across scales to connect and protect our irreplaceable landscapes—across public and private lands, and from cities to the wildest places.” (Network report page 6)

How do we know that this collaborative approach is on the rise? The report quotes a 2017 Network survey of 132 landscape conservation initiatives across the country that confirmed the dramatic increase in such efforts over the last two decades: “Nearly 90% of the initiatives surveyed have been founded since 1990, with 45 percent founded in the years since 2010…The [survey results] also suggest that we are seeing a fundamental shift in how we approach conservation…75 percent of the initiatives surveyed identified [themselves] as informal collaboratives.”

So what does landscape conservation mean in the context of collaborative approaches to protecting, enhancing, and restoring nature in cities? The report succinctly identifies three key evolutionary steps forward that are taking place:

A shift in geographic scale. Decades of scientific research have built a systems-level understanding of the natural world and have underscored the importance of habitat connectivity across scales. To sustain biodiversity, ecological function, climate resilience, climate mitigation, and other ecosystem services, conservation must transcend boundaries and move beyond a site-specific, parcel-by-parcel approach to the scale at which nature functions.

A shift in perspective. Wildlands, farmlands, rangelands, timberlands, tribal lands, places of cultural and historical significance, rural communities, urban areas, and other private and public lands are part of a whole system—a landscape. The landscape conservation perspective is that the entire landscape, private to public, developed to wild, should be considered together in a thoughtful and integrated manner when planning conservation action.

A shift in process. Landscape conservation crosses jurisdictional and topical boundaries, transcending traditional decision-making processes and organizational structures. The landscape conservation approach is generally characterized by a horizontal process and collaborative governance structure with long-term participation by a diversity of stakeholders.” (Network report page 6)

As Julie Regan, Co-Chair of the Network and Deputy Director of the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency in California/Nevada USA, accurately states: “We have entered an exciting era of epic collaboration.”

As a city and regional planner by training who always wants more nature in cities, my attention naturally turns to how to operationalize these ambitious and complex shifts to better protect natural and cultural resources. Although these shifts are challenging to implement, the Network report does an excellent job distilling down to the essence the key tasks for collaborative landscape conservation initiatives:

- Define Landscape Boundary and Need or Opportunity

- Identify Shared Vision and Goals

- Undertake Spatial Design and Strategic Plan

- Fund and Implement Strategies

- Evaluate Progress, Update Plan, and Adapt Over Time

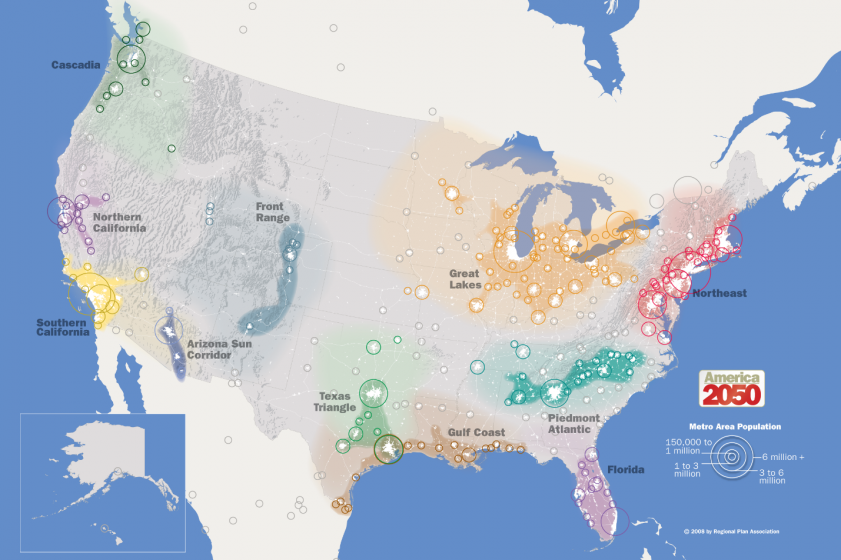

For the purposes of this discussion, I am focusing my attention on defining the landscape boundary and undertaking a spatial design. For cities, this boundary issue is a fascinating one, as large, interconnected networks of metropolitan centers increasingly serve as the focus of economic activity. Sometimes referred to as Megaregions, these areas have interlocking economic systems, shared natural resources and ecosystems, and regional transportation systems linking population centers together (see American 2050 graphic below). Megaregions currently account for about 25% of the USA’s land area, but include 80% of the population.

I think of Megaregions as areas that not only encompass a human footprint but also much of the ecological footprint required to maintain the existence of these dense human settlements. While the global marketplace provides many desired goods not readily available in most cities, many resources needed, and treasured, by communities come from nearby farmland, forestland, and natural areas. And increasingly, a small part of these needs are being met right next door to where you live (e.g. community gardens, urban forests, pocket parks).

People need resources—like clean water to drink, food from working farms, and fiber from working forests—from surrounding landscapes that remain free from intense urbanization and lie outside incorporated municipal boundaries. People also need (and want) nature (and agriculture) inside cities, and many new creative “local footprint” solutions are being implemented. Cities across the country are envisioning a world where humans, wildlife, and natural systems coexist in healthy, vibrant, resilient, urban communities.

In terms of undertaking a spatial design and strategic plan, Megaregions require mapping of a “green infrastructure vision” that integrates data across scales and landscape types. A detailed example of a strategic plan for the Chicago metropolitan region can be found here, while the spatial design associated with this green infrastructure network design methodology for Chicago can be found here. More and more metropolitan regions have developed green infrastructure visions, including Los Angeles, Nashville, and Portland, Oregon, and these visions tie well into the concept of the emerging trend of identifying a optimal amount of nature within cities and countries around the world.

With this combination of collaboration and available spatial analysis tools, we are entering what Emily Bateson, the Network’s Coordinator calls “a new transformative era” where “we increasingly embrace community-grounded and science-informed conservation at the landscape scale. This phenomenon is sweeping across the USA, continent, and globe, and represents our best chance to sustain the natural and cultural landscapes that in turn sustain us.”

Will Allen

Chapel Hill

Excelente artículo!, en el caso de una mega ciudad como Lima (PERÚ), existen limitaciones de carácter institucional para la gobernanza, desde el punto de vista territorial un enfoque limitado (sectorial/fragmentado), escasos niveles de comprensión y tratamiento a escala del paisaje (relaciones de dependencia hídrica, alimenticia, energética), y alta vulnerabilidad frente al riesgo de desastres.