Walking though the Bosnia and Herzegovina and the cities of Trebinje, Mostar, Livno and Bihac stirs up unexpected emotions. These cities reveal glimmers of how a country torn apart by war more than 23 years ago is rebuilding and where it is planting seeds of economic and social hope.

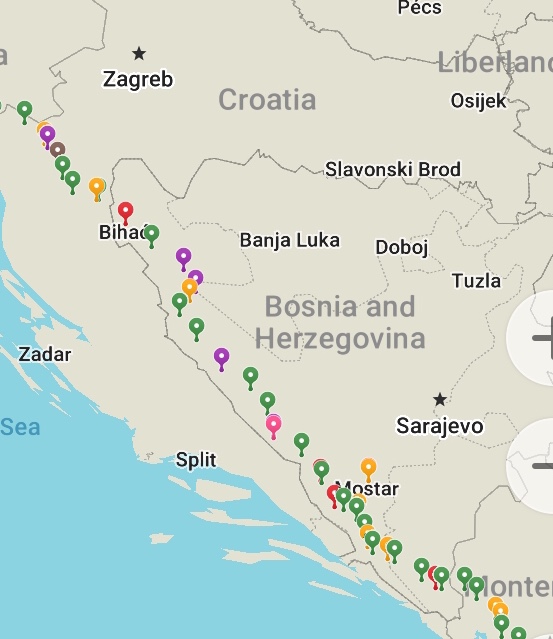

Our route takes us along mostly rural border areas wrapping around the south and west of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). It’s hard for me to process the disparate things I see each day. Beautiful mountains with thick pine forests. Warning signs about land mines nailed to trees. Wide open grasslands and lakeside wildlife reserves. Newly constructed houses decorated with flowerpots spilling over with colorful blooms. Facades riddled with bullet holes and houses destroyed by grenades. Villages abandoned by families fleeing war, and memorial stones remembering those who died fighting. Young and old people looking for a way forward.

The bigger cities of Trebinje, Mostar, Livno and Bihac help soothe the emotional unrest and physical discomfort that overwhelms me during humid summer days and rainy evenings. They offer some perspective that, perhaps, can only be appreciated slowly at three kilometers an hour. These cities reveal glimmers of how a country torn apart by war more than 23 years ago is rebuilding and where it is planting seeds of economic and social hope.

We finally reach the Balkans during the summer of 2018, and walk into Bosnia and Herzegovina on a hot day in August. It’s a milestone I simultaneously wished for and worried about since we set out from Thailand in January 2016.

Being in BiH means we are even closer to Barcelona, and closer to home, a concept that feels more significant after 2.5 years of journeying by foot. But, more than this tangible sense of nearing the end of a goal, BiH, in my mind, has for generations been a place where a reckoning with the ghosts of human tragedies and the need for great healing must one day intersect. I’m anxious about what our footsteps will lead us to see.

With absolute certainty, I can say our arrival to Bosnia and Herzegovina hits me on a deeply personal level, with Balkan blood shaping some strands of my DNA. I am half Croatian, and since the 1990s when images of war griping former Yugoslav regions flashed on my American television screen, I wanted to know BiH and its people loosely connected to me through veins of history, culture, traditions and distant family memories. Since antiquity, the roads of so many different lives and lifestyles have met in this East-Central European country, this land between worlds, and it made sense to us as we mapped our route that these same roads would gradually link our Asian and European footsteps.

What I didn’t expect, however, was the weight of walking through recovering war zones where we can feel the ethnic, religious and economic discontent simmering below the surface. It also had not occurred to me how it would feel to follow similar roads today’s masses of Asian, Middle East and African immigrants and refugees use to reach England, Germany, or other European Union countries. The impact of these various dynamics made BiH one of the most difficult countries for us to walk.

To lessen the sadness we still have a hard time describing, we meander through some of the country’s bigger southern cities, Trebinje, Mostar, Livno and Bihac, searching for solace in the day-to-day comforts of parks, riverside promenades, markets and coffee shops.

Turning to tourism

Perhaps not surprisingly after months of walking in open spaces and quiet, rural areas with few people, we are a bit deflated to see the throngs of tourists visiting Trebinje and Mostar during August’s peak vacation weeks.

The cities are clearly capitalizing on their proximity to the hyper-tourist seaside city of Dubrovnik across the border in Croatia.

Trebinje serves as base camp for vacationers who want cheaper accommodations than what they would find along the Adriatic coast 30 kilometers away, says a young man who helps his parents sell carpets and manage a holiday apartment while waiting for a call back to his better-paying seaman work.

In its own right, the small city, located in Republika Srpska one of BiH’s two legal entities, has enough things to keep visitors busy for a few days. There’s a pretty historic stone bridge, Serbian-Orthodox churches, and its main square has a market and is filled with restaurants, cafes and bars—essentials for hungry travelers. The dry, yellowed hills circling the city provide a dose of nature and panoramic views. I, however, live the city in a different way. I watch the sun set over the river while I fold our clean laundry, admiring the way the light shimmers on the water and not yet willing to immerse myself into urban distractions.

About eighty kilometers northwest from Trebinje, Mostar, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina entity’s economic and cultural hub with approximately 106,000 people and BiH’s fifth largest city, buzzes with day-trippers and bus groups. They crowd onto the reconstructed Ottoman-era “Stari Most” (Old Bridge) that was destroyed in 1993 by Croat military forces during the Croat-Bosniak war. They watch locals dive into the Neretva River and buy kitsch souvenirs that look more Turkish than Balkan from the dozens of shops squeezed on either side of the bridge. We stroll around the old city, and note the number of churches, monasteries, mosques, synagogues and religious-based cemeteries pointing to the historical ideological overlap that has shaped and continues to mold the city. It’s clear, though, that the city’s future heavily depends on tourism; the sheer number of hotels, hostels and apartments available for rent suggests that anyone who has a little bit of money is converting any space they have into rooms for sightseers making rounds from Dubrovnik to Sarajevo, BiH’s capital city further north.

We ponder Trebinje and Mostar’s development models on the strip of beach below the Stari Most, discussing the short and long-term pros and cons of such dependency. We eventually fall silent watching water birds hold their ground as the fast-moving river sweeps around them. How nature fits into cities under construction is far more interesting to us than scouring shelves for Turkish coffee pots and war paraphernalia.

The scars of war

Livno is the next notable town we wander through.

The city is in the Croatian Catholic zone of BiH. We know this because people throughout our BiH walk identify themselves and the cities they live in with both ethnic and religious distinctions. It’s one of the strangest naming encounters we have experienced thus far, but our conversations with various people of different backgrounds and residencies confirm that this dual label appears to be a new normal here. Post-war prejudices divide people into groups, we notice: Serb/Herzegovin Orthodox, Bosniak Muslims and Croatian Catholics. Livno is one of the cities that seems to reinforce the separation.

“The Croatian Catholics have rebuilt their houses. They are starting over, and want to leave memories of the war behind them,” a Croatian Catholic man in his 60s tells us while we wait out a storm. He grew up in a small village not far from Livno and travels from Zadar, Croatia, where he now lives, to take care of a house and garden his family own on the BiH side of the boundary line. “You’ll see this as you walk. About 20-30 kilometers after Livno, you’ll be in the Orthodox area. They haven’t rebuilt their homes yet. There are still bullet holes in their walls.”

We don’t know what to make of this kind of bigotry. It’s narrow-minded, dismissive, and shocking. But, we find ourselves in a state of astonishment as we walk and see first-hand what this man meant.

For a couple days of walking before Livno, we notice the houses and gardens. They are new, nicely painted, two or three-story single-family houses with porches, manicured gardens and fruit trees. There are nicer cars parked in the driveways, and better quality farm equipment.

This superficial affluence, a slightly different variety than we have observed elsewhere, takes on some airs as we enter the city. We see several local joggers and cyclists out exercising along the river, something we haven’t seen very of much of since we entered the Balkans. Women leisurely stroll the pedestrian street during the late morning and men at cafes hurry through their coffees. Kids walk by wearing soccer shirts brandishing the Croatian flag and names of Croatian players.

On the heals of Trebinje and Mostar, our couple hours in Livno give us a sense that BiH has turned a corner and is sort of patching itself together, at least from a rebuilding standpoint.

A few days later that image is erased with big strokes.

As the Zadar man predicted, we start seeing the signs of another reality further up the road. Villages are mostly empty, abandoned and forgotten. Houses are in a precarious state, their rooftops blown away and walls overgrown with vines. Pitted façades tell the story of rounds of bullets fired and forever lodged in the memories of those who still call these buildings homes.

“That’s from the Croat soldiers,” says an old Serb Orthodox woman, pointing towards the gaping hole in the wall near her second floor window. “We don’t have enough money to fix it.” She heads off to gather up her chickens for the night, a brief moment of resignation and frustration shades her smile as she leaves us to sip the Turkish coffee she prepared for us.

A few days further on, we see what hoped we wouldn’t see: Warnings about land mines hidden in the forest and roped off areas near deserted hamlets where teams are meticulously trying to find and detonate them. The lump in our throat that we first had when we saw a similar scene near one of the mountain passes in the Pamir region of Tajikistan returns. We do everything we can to not cry on the side of the road.

For many walking days, I wonder how people can stay in this country and why those who now have lives aboard would come back. I think about the unfairness of it all, and question what will become of BiH and what will happen to the cities and towns and the people who tell us of the limited opportunities and resources they have here. What is the just way to recreate BiH cities and villages, and how will they and the people who live in them conjure up enough resilience, social cohesion and financial support to reach a new plain of equality and livability? I have no answers, and tread forward in an uneasy silence for long stretches of time.

Winter is coming

The heaviness associated with the tragedy of war, human displacement and seeing people struggling to create a viable future sticks with me until Bihac.

Bihac, a predominately Bosniak Muslim city on the banks of the Una River, encapsulates the dilemma many European cities now face. Because of its proximity to Croatia (which is part of the European Union) and, thus, the shortest land route across Croatia to Slovenia (another EU country leading the way towards Austria, Germany and Italy), Bihac has become a holding place for thousands of transitory Asian, African and Middle East immigrants and refugees. People we met along the way and several newspaper reports estimate that anywhere from 4,000 to 10,000 migrants are currently living in grim, makeshift camps and occupying dilapidated, abandoned buildings in and around the city. No one really knows how many migrants are there, but concerns about how they will make it through the cold winter months are mounting. Locals themselves have a hard enough time getting through the winter. The care needed for this amount of homelessness is exponential.

“I’m living in a damp abandoned building. The guys at the hotel let me take a shower in one of the rooms that had to be cleaned,” an Algerian man tells us, coughing sporadically, while slowly sipping the soda we bought him at the hotel’s restaurant. We notice the two uniformed policemen who sit at the table behind us, watching us as they wait for their lunch. “I crossed into Croatia, but the police caught me, ripped up the documents the Bosnian police gave me and smashed my phone. Do you happen to have an extra phone you don’t need? But I know you could also get in trouble for helping me.”

If I did have a phone I could afford to part with, I would give it to him. I offer him a meal instead. He politely declines. We shake hands as we say our farewells, bidding each other safe passage on our respective onward journeys. He fades into the crowd of the many other migrants lingering at cafes, shopping at the supermarket and hanging out in the park near the river.

I feel the injustice, and it shakes me to my core. Lluís and I walk out in the open, on roads where everyone can see us, with passports us that give us the privilege to go almost wherever we want. This Algerian man and people like him, on the run from who knows what they left behind, use their phone’s GPS to track a route through mountains and forests that are home to land mines, wolves and bears. They hide in hope.

We pass over the river. Like in Trebinje, I watch the sun start to drop over the city. I watch the water flow, unaware of the human sadness hugging its banks.

I don’t know exactly where my footsteps will take me next. But, I, too, hold hope. I hope the cities of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the people who live in them will create a way forward that opens doors for all of them.

Jenn Baljko

Bangkok to Barcelona on Foot

Leave a Reply