A review of Masterpieces of French Landscape Paintings from the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts Moscow, an exhibition at the National Museum of Fine Art in Osaka, Japan.

Despite their lush depictions of natural scenery, French landscape painters were primarily Parisian urban dwellers. Biophiles, the lot of them too. From Monet to Rousseau, these painters often went as deeply and as often as possible into nature to do their painting, but they mostly dwelled in built up areas of Paris.

This collection of paintings spans the 17th to 20th centuries, and highlights not only how and why these urban painters progressively left their studios in Paris to venture into nature, but also follows the drastic changes within the urban landscape over the centuries. Thoughtfully arranged by the museum’s curators, the exhibition takes us through this progression in a way that explores relationships between the artworks, cities, and nature.

French tree huggers

Our walk-through of the exhibition begins with The May Tree, which may very well include the original tree hugger. You see the guy in the middle of the painting? While all his friends are courting women, he’s there hugging a tree.

Any exhibition that starts with an 18th century tree hugger has me on a hook.

The patrons of the museum seem equally infatuated—nearly every painting in the entire collection is mobbed with people. Mind you, we are here on a Wednesday afternoon.

I ask myself why these idyllic landscapes are so captivating. There is an obvious answer, which is simply that these bourgeois painters from the city brought to life landscapes that they connected deeply with, and people in turn connect with the resulting emotive works. There is something more than this though; a fiercely dedicated and evolving multi-generational cohort, these painters would often return to the same spaces in nature over their lives, to witness the infinite changes that take place through seasons and years. In doing so, they capture something peaceful and aesthetically pleasing, but perhaps more importantly, as urban dwellers, they capture the essence of something that they—and their fellow Parisians—were missing in their anthropocentric city.

If the mobs of Osaka urban dwellers standing around me at this exhibition are any indication, over centuries, some things never change.

Into the landscape of the city

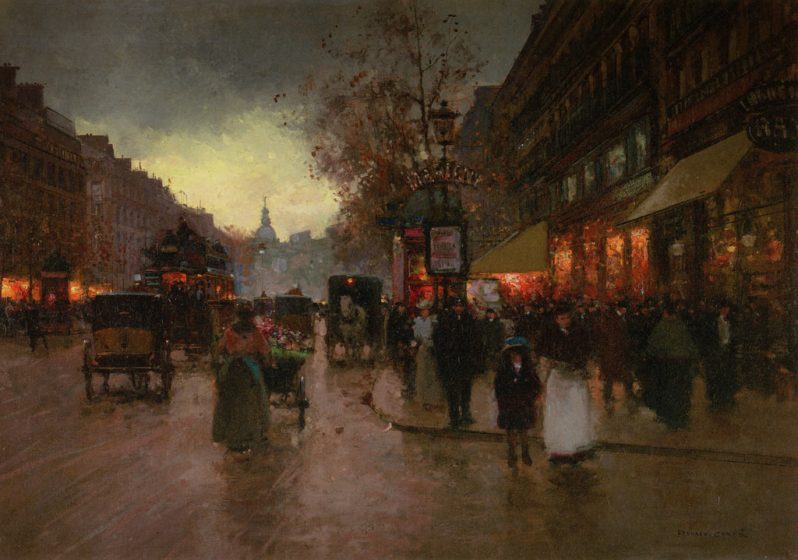

The city itself is not left out of the “landscape” genre here either. Further along in this Pushkin show is a collection of urban landscape paintings. The works highlight the massive changes in urban structure in Paris at the time of Napoleon III.

In the middle of the 19thcentury, Napoleon and Georges-Eugène Haussmann conducted one of the world’s most intensive—and massive—campaigns of urban renewal. Though it brought us one of the world’s favorite cities to be in, the urban reconstruction work is also sometimes likened to the largest gentrification project known to mankind. Indeed, thousands of poor citizens were unscrupulously booted to the fringes of Paris, their homes razed and replaced by broadways, statues, opera halls, and fancy apartments.

Curiously, in some ways the paintings here feel not dissimilar to contemporary billboards promoting some of the more garish urban renewal going on today; advertisements, idolizing a trendy, consumption-based high life.

The clothes have changed, but not much else has.

Without doubt, the works are alluring. In Paris at Night, a warm amber light filters through a slightly smoky air, in turn floating out to mingle with gray stone blocks, all of it set below the deep blue-orange gradients peeking out between sets of pitch-like clouds.

The color combinations alone provide some kind of primal comfort; mountains reassembled in ashlar, campfires turned to gas lamps. Human time changes, yet the power of such paintings must maintain a slower trot through time than we.

Walking across the room from the comfortable color combinations of Paris at Night, we are hit in the face with a wide-screen drama. Smoke. Not a gentle aesthetic treatment of fog. Manmade smoke. Something resembling grime. Not a new place.

For as dull a color pallet as it is, Smoke on the Paris Circuit Line glitters fabulously with apparent honesty. Luigi Loir does a number on us, sidestepping his peers at the time.

Let’s get real, folks. Trains and smoke.

The rainy, gray, wintry deceptions of Paris are many here, and they tell us too, something of the lives and interests of these painters.

Though France’s urban-dwelling landscape painters typically spent much of the year outside the city—in places like Barbizon and Fontainebleau—when things got frigid, these nature-lovers crawled back into their Parisian studios. This is perhaps one reason why Paris seems so often to appear decidedly in winter attire in their paintings.

Artists as nature preservation advocates

One intensely dedicated exception to this rule seems to be Henri Rousseau, who was so in love with the forest that he rarely went back to Paris at all, save for the necessity of selling his paintings.

So much did Rousseau love these forests, that he made a direct appeal to Napoleon III to stop Fontainebleau from being razed. The appeal seems to have worked; in 1853 Napoleon personally established a nature preserve there, protecting the forest that continues to be celebrated by artists and citizens to this day.

Moving through the exhibition, we exit the room, and exit the city again. We’re forward in time now. The advent of train travel—the gray smoky kind we found in Loir’s work—enables our painters to more easily get further from the city. The countryside becomes a regular destination for city folk.

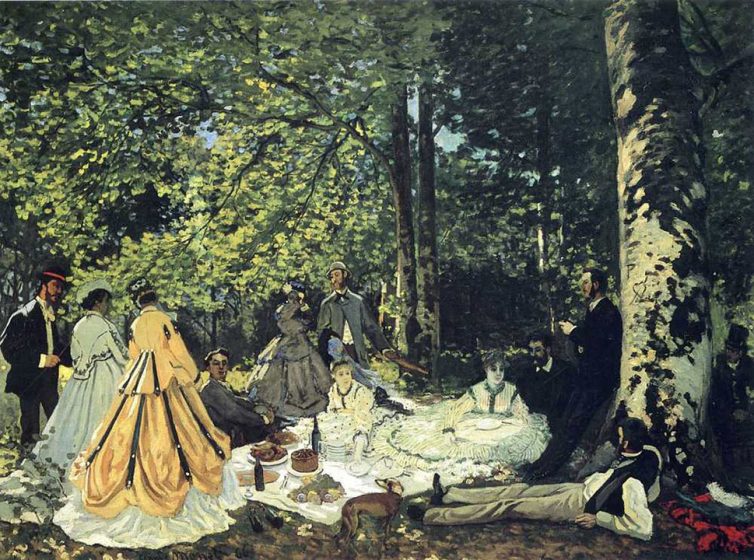

Here, Monet’s Luncheon on the Grass wows us. It’s one of the centerpieces of this show.

It’s also representative of your typical 19th century hipster party.

We’re treated to more Monet as we progress into this section of the exhibition. Indeed, Monet is well thought of for good reason. His works speak a truth that goes beyond representational realism.

“Try to forget what objects you have before you—a tree, a house, a field, or whatever. Merely think, ‘Here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow’, and paint it just as it looks to you…”. Monet realized that concepts of truth and realism exists only in a personal connection to the place you are attempting to speak about in your work.

In other words, a perfect, technically rigid depiction of a scene is a lie, unless the painter fully believes in it and enacts their own truth into their brush strokes.

Even if we can’t make out the faces, or the blossoms, we still can’t walk past Monet’s “Lilac in the Sun” without connecting to it in a way that we swear we’ve been there, in some life, in some too quiet, too peaceful moment. In some ways, standing in front of this canvas full of squares, oblongs, and streaks, there is no doubt that we are still there.

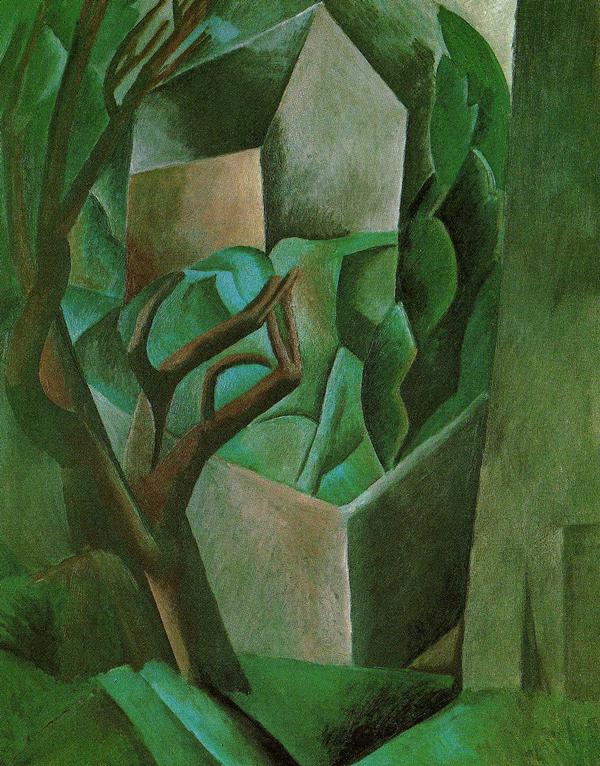

On our way out of this section, Picasso finally gets a chance to meet with us. His House in the Garden is unmistakable. In its twisting of visual reality, the house in the garden seems more like a garden picking up a house. The house rides, cradled, hoisted by a tree, on a wave of green.

Does it not?

We sometimes talk of Picasso’s visual truth being distorted, but certainly this isn’t the way to encounter Picasso! For here, nothing here is distorted. For Picasso, everything is in order, and what a joy it is to consider his conceptual truths in this way.

Picasso’s way of depicting garden and house as something of an integrated tapestry seems to me a kind of foreshadowing of cities to come, an attempt to mend the holes in our urban landscapes, not with a forest apart from the city, but with one fluid, intertwined work.

Forest as city?

Oh, the gems that good paintersleave for us to ponder.

Patrick Lydon

Osaka

Add a Comment

Join our conversation