But it was all The Fear of Snow

—Leonard Cohen, The Best

Yet winter is often depicted as evil and threatening, especially in fantasy and folk tales. One only needs to look at Game of Thrones and the menacing “winter is coming” motto of the house of Starks (Figure 2).

Inhabitants of cities that experience long, cold, dark winters, often dread the coming winter. Their everyday realities are closest to the last four imaginaries of winter in the city: cold, dark, dirty, and hazardous. In this article, I explore the winter ecologies of the city and the power those ecologies have in shaping the urban landscape.[iii]

Inhabitants of cities that experience long, cold, dark winters, often dread the coming winter. Their everyday realities are closest to the last four imaginaries of winter in the city: cold, dark, dirty, and hazardous. In this article, I explore the winter ecologies of the city and the power those ecologies have in shaping the urban landscape.[iii]

The Urban winter landscape

Before I write any more, I should admit that I love winter. I love the first significant snow fall of the season and there is something exhilarating about stepping outside and breathing air so cold your eyelashes freeze. But I grew up in central Alberta where winter can sometimes start in late September and last until the end of May (with some breaks in between because of chinooks—warm winds that blow off the Rocky Mountains). As such, my perspective on winter is a bit more upbeat than that of many people. My childhood winters were also spent on a farm, and I did not fully experience an urban winter until I moved away to attend university in Ottawa. Since then, however, I have experienced winter in a variety of cities in North America and for the past seven years I have lived in Montréal, Québec. But, my understanding and experience of winter is limited to the northern hemisphere. While several cities at far southern latitudes also experience some snow and cold during winter, their winters are much milder because more of the surface area is water and there are fewer large land masses.[iv]This article focuses primarily on winters in cities at northern latitudes.

The romantic imaginary of the winter city is very visible in Montréal, with its many parks and winter activities. Montréal is an example of a good “Winter City”, which is a concept and movement that developed in the early 1980s to encourage northern cities to become more livable and enjoyable through the creation of socio-cultural activities (see box 1 for a short description of the Winter City concept and movement). Montréal has a long history of winter cultures: skating rinks can be found in almost every public park, snowtubing and sledding, urban ski and snowboard parks, as well as many other cultural activities throughout the winter (Figure 3).

But the urban landscape in winter is not always pretty and fun. The snow is not pristine white but rather brown, yellow, and grey. Sidewalks and roads are messy. The photos in Figure 4 show snowy streets in Montréal the day after a snowfall in early January (2019).

The City of Montréal, for example, has a website dedicated to snow removal with the slogan “Promoting mobility during the wintertime” (Figure 5). The website outlines snow removal policies, processes, and other information.

Snow, ice, salt, and sand: managing the city in winter

Snow and ice for play in parks (and private yards) is desirable; snow and ice on sidewalks and roads is not. Snow and ice in desirable spaces can be understood as good winter natures while the snow and ice that get in the way of everyday routines are bad natures. Such bad nature is at the centre of urban management alongside other bad natures such as sewerage and grey water.

Snow removal

The snow removal process has made Montréal famous. Several years ago, the Boston Globe wrote an article entitled “Montréal Is Really Good at Snow Removal, Eh?”[viii] In the article, Sargent quotes a Globe and Mail journalist who argued that Montréal is

“…one of the snowiest major cities in the world, and its approach to snow is akin to the U.S. attitude toward Saddam Hussein—it’s an archenemy that should, ideally, be removed from the scene as fast as possible.”

Montréalers do indeed view snow as an object to eradicate (in certain places). The City of Montréal has a fascinating and relatively efficient system to eliminate snow, although many in the city would argue it is not efficient enough, but people outside the city seem to think otherwise, as the case with the Boston Globe article and the numerous videos on YouTube.

But removing snow and eliminating ice require the production of particular landscapes and ecologies in the city.

Spatial fix: snow dumps and chutes

The City of Montréal’s snow removal website outlines four stages of the snow removal process: salting, plowing, loading, and disposal. In many boroughs of the city, sidewalks (and sometimes bike paths) are cleared of snow before the roads (Figure 6). For sidewalks, salting and plowing are usually done at the same time, with tractors plowing the snow and spreading salt afterwards. The snow from the sidewalks is pushed to the ends of streets and becomes part of the street clearing process (Figure 7).

Tractors (sometimes a parade of them) plow the snows from the streets, then the snow blown into waiting trucks (see Figure 8).Approximately 180 vehicles are used for roads and 190 for sidewalks in Montréal to clear the entire city.

According to the City of Montréal, more than 300,000 truckloads of snow are loaded every year (12 million cubic metres).

Once the streets, sidewalks and bike paths are cleared, the city’s inhabitants no longer have to think about the snow. Their everyday lives are more or less back to normal. But few think about where this 12 million cubic metres of snow is put?

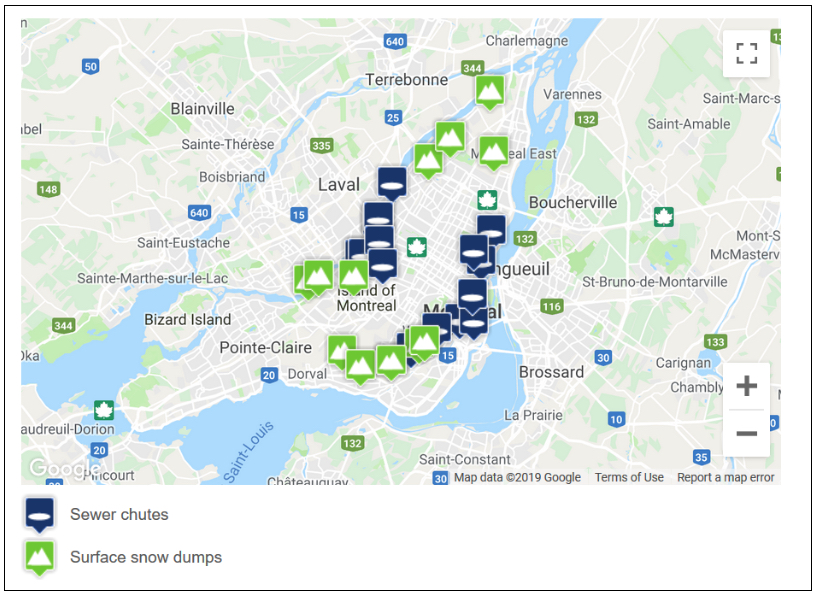

Cleared snow either goes into sewer chutes or surface snow dump.

The creation of large snow dump sites can be understood as a spatial fix for a temporary accumulation problem. Rather than deal with the snow where it falls and accumulates, the unwanted ‘waste’ in urban life is removed to an out of sight location. The unwanted snow no longer concerns urban inhabitants once it is not visible and in their way. Such a spatial fix is similar to how we remove garbage and grey water from our houses.

The ecology of sites like Saint-Michel is not well recorded. Snow can sometimes last well into the summer (and tends to blend in with the brown-grey colour of the cliffs because of the sand, gravel and other pollutants). During the spring and summer, the Saint-Michel dump also retains water (Figure 10, right photo). But the salt and other pollutants certainly have impacts on the ecology of site, as it does throughout winter cities.

Salt

Salt is still used in Montréal. Some cities have experimented with alternatives. Calgary, for example, recently began using beet juice to de-ice. Most cities, however, still use salt. Salt is spread with gravel and other abrasives (such as sand) on streets and sidewalks. In Montréal, an average of 140,000 tonnes of salt and abrasives are used each winter. But salt is also used by businesses, institutions such as hospitals and schools, apartment complexes, and homeowners. The aim of salting is to make it safer to move about the city. The use of salt is a touchy issue in cities such as Montréal. Icy sidewalks can be deadly for many elderly, children, and disabled, and not salting means that the city in inaccessible for them five months of the year. Many argue that salt is not necessary; that sand and gravel can be used alone. Indeed, there are a plethora of alternative products out there. However, if one looks at the porches of most houses and apartment buildings around Montréal, the usual bag of salt is visible. This is because salt is generally more effective and much cheaper

Yet while salt makes the winter city more accessible, it has numerous ecological impacts. Salt seeps into soils, runs off into sewer systems and waterways. In the case of Montréal, salt runoff into the St. Lawrence river is significant. The effect of road salt on aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems is well known. Some of the effects include groundwater salinization, changes in soil structure, accumulates in aquatic ecosystems which then alters the composition of fish or aquatic invertebrate communities.[xv] Road salt can also pose a danger to urban wildlife such as birds and squirrels who may ingest too much either directly or through plants.[xvi]

The use of salt also damages human property. An recent article in the National Post outlines the many ways that salt is corroding urban infrastructure, including roadways, bridges, and buildings, not to mention boots, clothing, and harming pets.[xvii] (Salt on sidewalks was a large motivation for the development of winter dog boots). As geographers Roger Keil and Julie-Anne Boudreauargue “…road salt [is] a formidable issue in the yearly rhythm of socio-ecological management in a winter city”.[xviii]

Salt is an integral part of the winter city. But it is also a part of the city’s spring, summer and autumn ecologies. The sorts of vegetation that is planted in parks, besides streets, and in front yards is dictated by what can survive the onslaught of winter salt. Some people try desperately to protect plants by covering them, installing winter fencing, or just not planting anything at all (Figure 11). Indeed, the ecologies and landscapes of the winter city can be said to shape the city much more than those of other seasons.

The dreaded “winter is coming” might need to be rephrased as winter is always here, despite being out of sight visually and mostly mentally (many Montréalers seem to suffer amnesia in the summer—they forget about winter as soon as spring arrives.)

The power of the winter landscape has not escaped planners and, as the below box on “Winter City” design illustrates, there have been several attempts to make the city more liveable and enjoyable in the winter. Yet, rethinking the use of salt and where we move snow in northern cities to make the winter city more ecological has been difficult. Indeed, my own love of winter activities depends on being able to walk safety to the bus/metro in order to access the skating rinks, sledding hills and winter cultural activities. Salt is seen as a necessary evil to create the ideal winter city.

Laura Shillington

Montréal

Notes:

[i]Sources: Ålesund https://www.pinterest.ca/pin/155585362111643598/?lp=true; Helsinki http://sun-surfer.com/winter-in-helsinki-finland-3189.html; Quebec City https://urbanguides.ca/eastern-canada/quebec/winter-bucket-list/

[ii]Source: https://imgnooz.com/wallpaper-383997

[iii]Note that I do not discuss economics of snow removal in this article given the limited space.

[iv]University of Santa Barbara Science Line: http://scienceline.ucsb.edu/getkey.php?key=6095

[v]Sources: Top left photo Smiley Man via MtlBlog (https://www.mtlblog.com/best-of-mtl/best-montreal-outdoor-skating-rinks); top right https://www.penteaneige.ca/home; bottom left https://www.tripsavvy.com/a-montreal-snow-festival-guide-2392574; bottom right https://montrealenlumiere.com/.

[vi]Source: Author

[vii]Source : http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/snowremoval/

[viii]Sargent, H. (2015, February 3). “Montreal Is Really Good at Snow Removal, Eh?” Boston Globe. https://www.boston.com/weather/untagged/2015/02/03/montreal-is-really-good-at-snow-removal-eh

[ix]Source: Author.

[x]Source: Author.

[xi]Sources: Frank Hashimoto (http://spacing.ca/montreal/2007/12/05/the-snowplow-ballet/)

[xii]Source: City of Montreal (http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/snowremoval/elimination-neige#carte-elimination)

[xiii]Source: Journal Metro (http://journalmetro.com/local/lasalle/actualites/689037/lasalle-a-le-plus-gros-depot-de-neiges-usees-a-montreal/)

[xiv]Winter Source: L’arrondissement de Villeray–Saint-Michel–Parc-Extension (ville.montreal.qc.ca/vsp ); summer source: Olivier Lapierre (On Twitter, Septembre 26, 2018: https://twitter.com/O_Lapierre/status/1045033259749572609)

[xv]Learn, J. (2017, 26 May) The Hidden Dangers of Road Salt. Smithsonian Science. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/road-salt-can-disrupt-ecosystems-and-endanger-humans-180963393/and Tiwari, A., & Rachlin, J. (2018) A Review of Road Salt Ecological Impacts. Northeastern Naturalist 25(1). https://doi.org/10.1656/045.025.0110 .

[xvi]Findlay, S. E., & Kelly, V. R. (2011). Emerging indirect and long‐term road salt effects on ecosystems. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1223(1), 58-68.

[xvii]Hopper, T. (2018, 22 Jan) How Canada’s addiction to road salt is ruining everything. The National Post. https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/how-canadas-addiction-to-road-salt-is-ruining-everything

[xviii]Keil, R. & Boudreau, JA. (2006) Metropolitics and metabolics: Rolling out environmentalism in Toronto. In Heynen, N., Kaika, M. & Swyngedouw, E. (eds) In the Nature of Cities: Urban Political Ecology and the Politics of Urban Metabolism, (pp. 56-77). London: Routledge.

[xix]Source: Author.

[xx]Source: https://fantasticdl.wordpress.com/2014/11/24/12541/game-of-thrones-winter-is-coming/

Merci Yves !

J’ai commencé à étendre le projet puis le COVID est arrivé, mais je reprendrai mes recherches en juin 2023. Mon idée est d’examiner les dimensions sociales, écologiques et politiques, dans le contexte du changement climatique (par exemple, les tempêtes de verglas) et du “métabolisme urbain”. “.

Intéressant et très juste. Avez-vous publié d’autres textes sur le même sujet? Avez-vous l’intention de pousser la recherche plus loin?

Ces dernières années, le traitement de la neige par la Ville de Montréal a été amélioré en efficacité et en attention envers les cyclistes et les piétons, mais les problèmes de pollution demeurent. À ceux que vous signalez s’ajoute le déploiement de machinerie lourde qui ajoute à l’effet de serre et cause des dommages importants aux chaussées, trottoirs et autres équipements urbains…