about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

Before I founded TNOC, I spent almost 15 years as a full-time theatre artist. It is sometimes said that theatre is the “most collaborative” of the arts. It is certainly an intensely collaborative form, and this aspect is what I love most (among many things) about theatre.

And even in theatre, collaboration can take on various forms. There is a well-known kind of serial collaboration, in which a play is written, a theatre decides to produce it and hires a director, the director works with designers (costumes, lights, set, sound) to create the world, the director selects actors, and all set about to make an experience and say something … maybe for an audience. Another form of theatrical collaboration goes back to Shakespeare and others (see, for example, the depiction in the movie Shakespeare in Love) in which the actors come first, or at least together at the outset with other contributors, and everyones dives into creation.

Both are joined by an idea: that together, we create something we could not have created by ourselves.

When I first encountered “urban ecology”, and urbanism generally, what attracted me was the essential collaborativeness of cities and their design—that cities are, or at least should be, collaborative creations. Indeed, this is the fundamental (and ideally fun) and foundational idea of TNOC: let’s put different types of people into the same space and see what emerges.

So, we asked a collection of TNOC contributors—scientists, artists, planners, designers, engineers, policy makers—about their own experience with collaboration. Specifically, we asked:

What is a specific experience you have had in your work with collaborating on a project with someone from a different discipline or “way of knowing” or “mode of action”? What was good about it? What was challenging? What did you learn or produce that could not have happened without this collaboration across difference?

It is a rich vein of response, and some threads stand out about the collaborative experience:

- It challenges us to trust.

- It is often surprising.

- It is often difficult.

- Sometimes there is tension.

- It takes time.

- It demands personal growth.

- It requires acknowledgment of others.

- It asks us to question our own points of view.

- It thrives in the in-between spaces.

- There is no one way.

- It is an act of transformation.

I suppose collaborative work is not for everybody. But have a look here, and imagine where your ideas might go as you engage with difference.

By the way, this is also the spirit of The Nature of Cities Summit. Perhaps we’ll see you there.

about the writer

Pippin Anderson

Pippin Anderson, a lecturer at the University of Cape Town, is an African urban ecologist who enjoys the untidiness of cities where society and nature must thrive together. FULL BIO

Pippin Anderson

Between 2010 and 2012 I was mandated to run an Urban Ecology CityLab, as one of a suite of CityLabs run through the African Centre for Cities in Cape Town, South Africa. The idea was to broker greater engagement between academia and society on the understanding that the most pressing problems facing cities will be best attended to by drawing on the expertise sitting both within academia and society. The Urban Ecology CityLab took the form of a series of seminars around specific ecological themes or issues in the City of Cape Town, and included some meetings off campus and field trips. Invitations went out to a diversity of groups and people, via various mailing lists, with the hope that we would draw as diverse a crowd into the room as possible. The hope was to have a group of people in the room that could challenge the status quo, add new insights, and shed light on existing problems from entirely different angles.

Every time we met, I held my breath as there was always a chance that no one would show up. It never happened. Not once did I end up in a room alone. There was always a good enough crowd who came along and make for a meaningful discussion. But that said, in almost every instance the attendees were ecologists. And in almost every instance ecologists with an interest specific to the topic at hand. So, if we were planning to talk about urban rivers, the room would be full of riparian ecologists. If we were planning to talk about conservation areas in the City, the room would be full of plant ecologists. So, while the people who were there were undoubtedly from a different “way of practicing”, where they came from NGOs or were City officials or consultants, and shared a disciplinary understanding.

There were some definite lessons to be learnt in this process. If you really want to get a diversity of people in the room, how you go about posing the question is critical, and you need to be disrupting disciplines at that point already. To achieve sustained engagement and the development of a community in these new spaces presents a particular challenge. Ecologists are—well I believe anyway—inherently conservative and not inclined to step readily outside of their comfort zone. Meetings off campus, and in particular in the field, attracted a greater diversity of people. Evidentially where you meet is also very important, and a lot of people are put-off by academic spaces. We had lots of interesting conversations and in the end did some fun writing together, but I was not sure I ever really brokered the different communities as I had hoped to.

Probably the most significant positive outcome was my own personal and professional growth. The literature is full of tales of woe and warning when it comes to collaborative work, but until you jump in and try you will never know what those specific or particular stumbling blocks might be in your case, and similarly you will never know the pleasure of having your own views challenged.

about the writer

Carmen Bouyer

Carmen Bouyer is a French environmental artist and designer based in Paris.

Carmen Bouyer

It is a pleasure to talk about the so nurturing collaboration with the talented all organic chef Anne Apparu-Hall. We had been put in touch several years ago in Paris but had never met, when a new friend in New York connected us again. I remember meeting Anne for the first time at the Edgemere Farm weekly market, a lush half-acre urban farm that had bloomed on an empty lot in Far Rockaway, Queens (New York). It was a perfect place to meet such a woman! The stroller were her beautiful daughter was sitting was also full of locally grown organic vegetables, flowers, and herbs. After sharing a colorful meal at her house—just five minutes away from the farm —we realized how her work as a chef, educator and environmental activist, often working with art institutions, was closely related to mine as an environmental artist and designer. Our shared passion for bringing people together in a happy way and making organic food accessible in cities convinced us that we had to do something together.

Already, as a facilitator of the Red Hook Community Farm C.S.A (an other striving urban farm) at Pioneer Works art center in Red Hook, Brooklyn, I had noticed that we had weekly food leftovers from the shares. People who couldn’t come to take their food baskets that week and also an extra abondance at the farm that gave us very full crates of all kinds of delicious veggies. Along with Corey, the farmer, we wondered what to do with this food and came up with the idea of doing a weekly community lunch on the day after the weekly CSA deliveries.

Already, as a facilitator of the Red Hook Community Farm C.S.A (an other striving urban farm) at Pioneer Works art center in Red Hook, Brooklyn, I had noticed that we had weekly food leftovers from the shares. People who couldn’t come to take their food baskets that week and also an extra abondance at the farm that gave us very full crates of all kinds of delicious veggies. Along with Corey, the farmer, we wondered what to do with this food and came up with the idea of doing a weekly community lunch on the day after the weekly CSA deliveries.

All we needed was a chef interested in co-organizing a hyper local community lunch.

We soon started to imagine a shared meal with Anne, her husband Edward Hall, along with Pioneer Works team. We united through a common vision for environmental art practices,community events and convivial access to restorative grown food. It was a great success. With 30 to 40 guests a week, from July to November 2016, the community lunch at Pioneer Works was welcoming a large part of the staff, some neighbors, and visitors, for a cost of $8 (suggested donation). It became a weekly celebration of the passing seasons in sharing nourishing food from the land we inhabit and inspiring sustainable practices to our guests, from offering only vegetarian local food, to creating an “all compost”waste system, chemical-free, communal experience.The meal was a fruitful collaboration between environmental urban activists, from committed urban farmers to city parks foragers, as well as upstate grain and fruit growers and dairy farmers. We would add to the mix the beautiful food grown in Pioneer Works’s garden by permaculturist and ecologist Marisa Prefer.

Working with Anne I learned that cooking was first of all a collaboration with many food producers, and often more, whose work would nurture and inspire you. Through these food lovers, we would learn about the local nature, what the weather had been, what was in bloom, what was in fruit. It was above all a collaboration with our immediate environment and its gorgeous fertility, even in the center of New York City!

This sense of abundance was enhanced by Anne’s ways of creating her copious shared meals. Always so creative and free. Because every week the available fruits, vegetables and herbs were a total surprise. Depending on what food would be leftover from the day before and what could be foraged that week, Anne had developed a graceful way to welcome those surprises into her meals. She would simply lay out all of the available ingredients on the kitchen table and look at them for a short while, taste them if needed, mixing colors and textures and then, very fast, in a sort of magical way, her intuition would tell her what the menu will be that day. I would write down that flow of inspiration, make a spontaneous drawing expressing the overall emotion it brought and send that invite to our mailing list. With Anne and her ability to celebrate being alive through preparing a community feast, I could experience the sacredness of food and its raw power to bring people together in a safe space for encounters and conversations to happen.

Because cooking is very much an art, and a practice that is profoundly connected to the land were food grows, the collaboration flowed very easily. As an environmental artist it opened new perspective on what art really meant for me, I realized that it was simply the art of living together that moved me so much. This refined art : in essence a conversation, a co-creation, a community meal of some sort, a place where each guests can feel nurtured and thrive.

And how best could we develop this life sustaining art but by collaborating with as many people as we possible can?

about the writer

Lindsay Campbell

Lindsay K. Campbell is a research social scientist with the USDA Forest Service. Her current research explores the dynamics of urban politics, stewardship, and sustainability policymaking.

Lindsay Campbell

We collaborated with Kekui Kealiikanakaoleohaililani, who is the kumu (master teacher) and catalytic force behind the Hālalu ʻŌhiʻa Hawaiian stewardship training. This training is immersed in a Native Hawaiian world view, using multiple modalities to get participants thinking and feeling in new ways.

Working with Kekuhi to plan the workshop was inspiring, humbling, and as my colleague Heather McMillen shared about her experience writing a chapter with Kekuhi, “like putting fireworks in a box”. I am very orderly in my notetaking, project management, and have an ever-present “to do” list. While that can lead to productivity, it can also be quite rigid. Every time we spoke with Kekuhi, our ideas for the structure and content of the workshop were transformed. I left refreshed, but also sometimes befuddled. I would have to trust, to leave some space and room for not only her wisdom and approach, but also for the collective, beautiful, crazy wisdom of the group that would emerge.

Our workshop had no powerpoints, lectures, or panel discussions; instead, it included singing mele, dancing hula, making hei string forms, and building a kuahu (altar). From there, Kekuhi taught us to use the conceptual framework of kiʻi to analyze origin stories from all over the globe, and to write our own stories connected to our observations of place. We later wrote (and performed) our own mele to honor the plant, rock, and water people with whom we feel special connections.

I would never have predicted that I would be chanting my own mele, “Oh, Stone!” in honor of the Petoskey Stone (state stone of Michigan, fossils from an ancient inland coral sea) and my Midwestern connections to it in front of 50 professionals. Or that some of those colleagues would be wriggling like eels on the ground, making their journey from the Sargasso Sea. Or that others would be brought to tears in offering stories of childhood, of home, of family, of place. These memories are seared into brain as a shared experience where our guards came down, our hierarchies were shed, and our traditional roles as “agency representative” or “scientist” or “land manager” were transformed. We began to treat each other, as well as the nonhuman others in our surrounding landscape—a bit more like kin.

But how do we carry it forward? Where do we go from here?

Inspired by Learning from Place, we launched a series of monthly “Stewardship Salons” with a loose group of about 15-25 folks engaged with caring for New York City. We are a rotating community of teachers and learners—and we are operating without a master teacher, and without the scaffolding of any one particular worldview. But our diversity and flexibility is also our greatest strength. We have visited places and engaged topics ranging from examining the histories of Central Park and the displaced Seneca Village, to sharing a Tu B’Shevat seder and exploring Jewish environmentalism, to building a group conceptual model of stewardship in the city. So, I am learning not only from the content shared by all the other teacher-learners, but by the process of remaining radically open to where we might head, together.

about the writer

Gillian Dick

Gillian is the Manager of Spatial Planning – Research & Development team within the Development Plan Group at Glasgow City Council.

Gillian Dick

Collaboration in a real world setting

My first positive experience was working with European geological surveys and local authorities within the COST Suburban . Sub-Urban is a European network of Geological Surveys, Cities and Research Partners working together to improve how we manage the ground beneath our cities. There was a realisation that the Geologists had a lot of interesting and useful GIS based data that urban planners within local authorities were either not aware of, or just not using. In some cases it was known knowns, but also known unknowns. The best analogy was that the Geologists were running a stall with lots of great products, but we as practioners were only interested in the one product we understood and knew. How could the geologists move us from risk averse to risk aware? It also felt like we were all talking different languages and explanations and understanding were getting lost in translation. Through the project we collaborated on developed a shared language that allowed the delivery of a toolkit that helped planners identify their information requirements in relation to the sub surface and linked them to the data that Geologists had available. We had shared ownership and understanding of the objectives and outcomes and a shared responsibility to deliver.

My second example is Connecting Nature, large research and policy project funded by the European Commission. Academics recognised that in order to impact actions on the ground with regard to their research into nature based solutions they had to recognise the large body of work that local authorities had already developed. They had to recognise that innovation could come from communities as well as the academic world and that they had to understand the needs of practioners and identify useable tools and methodologies that worked with the realities of local authority governance. There was a recognition that research aims can be served by working on real world problems that currently exist and not on “pilots” that have just been created to service an academic need. We’re only a year and a bit into Connecting Nature, but it feels like a real collaboration that has the potential to change how Local Authorities work with academics. It will also, hopefully show the wider academic community that local authority practioners do have a scientific rigour underpinning the work that they deliver, and that there is real value in social science in a real world setting. Collaboration is about real partnerships built on a trusting relationships where each contribution is valued equally.

about the writer

Tischa Muñoz-Erickson

Tischa A Muñoz-Erickson is a Research Social Scientist with the USDA Forest Service’s International Institute of Tropical Forestry (IITF) in Río Piedras, Puerto Rico.

Tischa Muñoz-Erickson

The main challenge the ranchers and I had to overcome to work together on this knowledge system was one of trust because of the conflict that ranchers have had experienced with environmental activists in the past. My advisor at the time was a conservation biologist that had been working with the group for many years and that the ranchers now trusted. Yet, I couldn’t rely on his social capital alone, but I had to build my own rapport the ranchers as well. I visited the ranches many times to have coffee with them. I participated in campouts and other social activities that the Diablo Trust organized to encourage community cohesion. I walked the land with them, and I volunteered when they needed help to move the cattle herds or to put up fences. I even wore cowboy chaps one time (yes, you read right, this urbanite from a Caribbean island wore cowboy chaps!). I had to do all that so they would see that I respected their way of life and that, while sometimes we may disagree over specific management actions, caring for the land was a value we held in common and that it could be the basis of our professional relationship. Once they trusted that I was not trying to impose my environmental views on them, they were willing to listen to me and see the importance of studying and monitoring things that I also cared about (i.e. rare plant species) along with what they cared about (i.e. productive grasses for their cattle).

Thirteen years after I left the project, the knowledge system we developed together is still being used by the Diablo Trust. I am also still welcomed as a friend and colleague to their regular meetings. There is not better indication that our collaboration was a success as seeing them take ownership of the project and sustain it beyond my time there.

But the greatest impact this collaboration had on me is that it made me confront the unconscious (and naïve) bias I had towards scientific knowledge as a superior form of knowledge. All that time I spent building trust with the ranchers also allowed me to see and learn from the deep knowledge they had amassed from growing with and managing the land. The humility and appreciation I gained for other ways of knowing, and that now is the foundation from which I approach every collaboration, could not have happened if I hadn’t had experienced ranching and this different way of seeing and experiencing the world.

In short, the positive and productive collaboration I had with ranchers taught me that building relationships and inclusiveness across different worldviews and ways of knowing are crucial ingredients for a successful collaboration. The time and energy invested in these key ingredients will not only result in better project outcomes but, more importantly, the work and its impact (and the friendships!) will be more meaningful.

about the writer

Eduardo Guerrero

Eduardo Guerrero is a biologist with over 20 years of experience in projects and initiatives involving environmental and sustainable development issues in Colombia and other South American countries.

Eduardo Guerrero

Towards a multi-stakeholder approach to sustainable management of urban wetlands in Bogotá

These urban wetlands are the living memory of a great high Andean lake system that once characterized the indigenous Muisca territory, in what we now call Sabana de Bogotá.

Although fragmented relicts of large aquatic spaces, still today they offer us an amazing biodiversity in the middle of the big city. Their ecosystem services are essential, either as biological filters, water regulators, microclimatic regulators, carbon storage or as high-value natural spaces for citizen enjoyment.

During the last 25 years a synergistic process involving public and community stakeholders has been successful in halting an intense deterioration caused by irrational urban planning.

They have been legally declared as District Ecological Parks, which are fundamental elements of Bogota’s Main Ecological Structure and district water system. The rationale behind this declaration includes the understanding that the economy and competitivity of the city depends on its natural base of support.

Even amid divergent points of view and occasional lack of trust among authorities and citizens, a shared goal to protect these strategic urban ecological parks has gradually gained momentum.

An intense and necessary debate is part of the process. Should the urban wetlands be dedicated strictly to passive recreation? Considering they are natural areas located in the middle of the city, is it possible to reconcile the protection of their ecosystem attributes with land uses such as walking trails, bike paths, park furniture (benches, viewing platforms, fitness equipment) or even the nearby planning of avenues? What should be the distance between urban infrastructure and wetlands, and what is the type of protective barriers or urban design needed to preserve ecosystem functions? What activities should be allowed and under what criteria should the carrying capacity be managed in such a way that ecotourism and visitor access are compatible with conservation and sustainable use?

During recent years, my own experience with this intense process has comprised several roles. It has allowed me to experience personally a diversity of perspectives and interests regarding urban wetlands. Let me share some specific experiences I have had in my work in collaborating with stakeholders from different disciplines or “ways of knowing”.

- As a citizen, I participated in a community-led initiative, in which neighbors collaborated to build a kind of “social mesh”, instead of a physical mesh, looking to protect a public wetland area through environmental education and citizen ownership.

- As a manager in Bogota’s environmental authority, we enriched wetland park management by recruiting community leaders as environmental interpreters and guides for visitors.

- And currently, as an advisor of the national policy on urban environmental management, I have organized a multi-stakeholder think tank devoted to promoting dialogue and exchange of good practices among interested parties in public, private, academic and community settings.

In all these experiences I encountered a genuine interest in joint action beyond disciplines and points of view. When you establish a common ground around a shared vision, as well as a “win-win” mood, interest, and actions tend to converge.

Of course, there still are conflicts of interest, misunderstandings, and sectoral and political biases, but gradually and increasingly more and more stakeholders recognize urban wetlands as a patrimonial and strategic element of Bogota’s natural heritage.

Clearly, dealing with urban wetlands is not just an environmental issue. You must involve strategic sectors and stakeholders including habitat and urban planning, the construction industry, infrastructure, health, education, security and, of course, community organizations. It’s a complex challenge that requires integrated approaches as well as governance based on transparency and participation, the building of trust, and joint action.

In Bogota, we have a promising process in which there is not a single stakeholder leading the recovery and protection of our urban wetlands, but a synergistic arrangement of committed public, private and community participants. In the midst of agreements, disagreements, constructive debates, and conflicting interests, the social imaginary regarding urban wetlands is evolving towards a recognition of the multiple values and ecosystem services provided by them.

Few Latin American capitals have the quantity, biological diversity, and the extent of wetlands like Bogotá, both in the city and in rural areas. We should be proud to have a wetland system that represents a natural heritage, and that has become a major city project. And at the same time, we must be more and more committed to and co-responsible for their protection and coordination of a sustainable, inclusive and resilient development of our capital city.

about the writer

Britt Gwinner

Britt Gwinner works on affordable housing in developing markets. He has led investment and advisory programs for affordable housing finance for the past four years, with most experience in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia.

Britt Gwinner

As a banker, I’ve struggled to collaborate with my engineering and architectural colleagues to define and finance affordable, green, and disaster resilient housing. We have had some success, but it’s been an on-going discussion about how to pitch the value proposition to individuals, what is feasible in technical terms, and what is feasible in economic terms, especially for low-income families in developing countries.

Building efficient, resilient, affordable housing ought to be one of the easy ways to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and improve urban disaster resilience. Close to 20% of GHGs come from buildings, and in the urbanizing world, housing makes up 75% of new structures. In earthquakes and cyclones, housing usually suffers more than robust commercial structures.

But globally, most new housing is built in developing countries by low income households. Families start with pieces of land and build shelters incrementally, room by room. These families cannot afford to follow basic local building codes, much less global norms for energy efficiency. Up to 70% of the workforce of countries like Indonesia and Kenya work informally, without a regular paystub. Banks will not provide informal workers with mortgages to buy completed houses.

Financing is essential to any kind of real estate. Neither low income households nor wealthy investors pay cash for real estate. Formal real estate construction brings together teams of engineers and architects, who design the building, and teams of financial specialists, who figure out how to finance the building’s construction. Informally built housing brings together low-income households with often low-skilled artisans and a wide variety of materials and methods.

To an engineer or architect, the advantages of green technologies are obvious, based on climate change mitigation and future savings for the families. But these savings can be small in a temperate or tropical climate, where it is not necessary to heat a home. For commercial structures, communications among professionals are easy. Investors in a new warehouse are happy to reduce future operating costs with energy and water saving tech.

The struggle comes in affordable housing, where even a middle-class household that buys a flat in city like Jakarta may scrimp for years to save up a down payment. Any additional up-front cost is a serious challenge, even if it leads to lower electricity bills in the future.

Resilience to disasters can be even more difficult to sell to poor households. Installing plumbing in a house that lacks it is a sure gain in hygiene and health for a family. Depending on the location, reinforcing the structure against earthquakes is an uncertain gain against a distant, potential calamity.

To a low-income family or a financier, the cost benefit tradeoff of energy efficiency and resilience is not always obvious, because the calculation is made solely in terms of the direct costs to the owner. What is the technology package that is cheap enough for a low-income household in an informal neighborhood in Jakarta? How do we convince microfinance institutions to finance LED lights, solar water heaters or structural improvements? How does the microlender assess the capacity and willingness of the informally employed household to repay a loan for that technology package?

As a lender with social science background, I’ve been learning about the mix and match of different green technologies for different climates and countries. On the other hand, I’ve had to school my engineering colleagues on how banks and micro-lenders function.

We are having some success. In recent years, we’ve financed more and more green, resilient housing. The challenges are generally found in the institutions that build and finance housing, from authorities for building codes, materials producers and distributors, lenders, and the households themselves.

The construction business is conservative, as are consumers. Housing is an aspirational good. People identify with their homes. We’ve all had to learn what building materials are culturally acceptable in different countries, and how we might convince people to accept new technologies.

The shortfall in affordable and resilient green housing is a microcosm of the broader debate of thinking globally and acting locally. What can seem like an obvious gain to an engineer may not be as clear to the family that has to pay for the technology, or to the lender that would finance its purchase. But engineers and lenders at many lenders are working to express the value proposition more effectively.

(The opinions expressed In this post are my own and not necessarily those of my employer.)

about the writer

Keitaro Ito

Keitaro is a professor at Kyushu Institute of Technology and teaches landscape ecology and design. He has studied and worked in Japan, the U.K., Germany and Norway and has been designing urban parks, river banks, school gardens, and forest parks.

Keitaro Ito and Tomomi Sudo

What is urban ecology and biodiversity? What have we learned from collaborative ecological landscape design in urban area? We have been designing landscape even in urban areas, based on vernacular design (ecology, regional culture, and so on) for the past decade. The aim of our projects is to create an area for preserving biodiversity, children’s play, and ecological education that can simultaneously form part of an ecological network in an urban area. In these past 15 years, I have been designing to have interdisciplinary research and proposing to accommodate both children’s play and biodiversity in an urban area. I would like to discuss the problem and future issues through our projects, exotic species, children’s play, and managing urban nature from a landscape designer’s point of view.

The Multi-Functional Landscape Planning (MFLP, Ito et al. 2014, 2106) method has been used for the projects. MFLP approach will be effective to evaluate for the planning of a project such as urban park. According to this method, a space is divided into a number of layers (layers of vegetation, water, playground, and ecological learning), which overlap each other. Thus, during the creation of a multi-functional play area, children are able to engage in “various activities” as its different layers are added on top of each other. In addition, they will learn something new about its ecology when they are playing there. The ecological rich place is thought to be a more vivid location for play. The project drew on two planning processes. First, “process planning” was used in the planning and design phases of this project (Isozaki, 1970). This does not place emphasis on the finished object but allows changes to be made during the actual process and is thus a very flexible method of design. The children learned about the existence of various ecosystems through their participation in the various workshops (and then later when playing in the biotope). Children and teachers at the school, along with a number of local residents, actively participated in the development of an accessible environment (the biotope) and are active in proposing ideas for its future management. As such, their interest in the biotope continues. “Process Planning” would thus appear to be well suited for a long‐term project such as a school biotope.

The aim of these projects is to create an area for preserving biodiversity, children’s play and ecological education that can simultaneously form part of an ecological network in an urban area. Then we need to communicate ecological matters to children, parents, and teachers. In our school yard nature restoration project, the collaboration has been done with landscape designers, university students, school teachers, educators, ecologists, and psychologists. In this project, we have done over 350 workshop together with children, teacher and university students. They discussed their own ideas about ecology, target species, depth of water, domestic plants, and so on. University students especially have a very important role for connecting ecological knowledge between teachers and school children. For example, exotic species are sometimes difficult because, while some of the flowers are beautiful, they may need to be eliminated for native biodiversity conservation purposes. Students’ teaching skill is key. They need to learn and study basic and ecological matters.

I think landscape designers should consider “landscape” as an “Omniscape” (Numata 1996; Arakawa, 1999; Ito et al. 2014, 2016) in which it is much more important to think of landscape design as a “learnscape”, embracing not only the joy of seeing, but stimulating a more holistic way of using body and senses for learning. So it is very important to see how children and teachers are using urban nature, then landscape designers can flexibly adapt the plan for the place according to their needs. Landscape designers and architects need the ssupport of biologists/ecologists for ecological design and planning.

References

ITO Keitaro, Tomomi Sudo and Ingunn Fjørtoft, Ecological design: collaborative landscape design with school children, Children, Nature, Cities, (Eds.) Ann Marie F. Murnaghan and Laura J. Shillington, Routledge, pp.195-209, 2016

ITO Keitaro, Ingunn Fjørtoft, Tohru Manabe and Mahito Kamada, Designing Low Carbon Societies in Landscapes, Landscape Design for Urban Biodiversity and Ecological Education in Japan: Approach from Process Planning and Multifunctional Landscape Planning, Springer, pp.73-86, 2014

Arakawa, S. Fujii, H. (1999) Seimei‐no‐kenchiku (Life architecture), Suiseisha, Tokyo.

Numata, M.(1996) Landscape Ecology, Asakura shoten, Tokyo

Isozaki, A.(1970) Kukan e (Toward the space), bijyutu shuppan, Tokyo (in Japanese)

about the writer

Tomomi Sudo

Dr. Tomomi Sudo studies for developing sustainable cities which can provide essential nature experiences for people and children. She has been implementing ecological learning projects for children in urban natural environment. She is studying also Landscape Ecology and Design in Japan and Norway. Her interest is how to develop the materials for ecological education and apply that for ecological design. She studies at Kyushu Institute of Technology, Japan.

about the writer

Madhusudan Katti

Madhusudan is an evolutionary ecologist who discovered birds as an undergrad after growing up a nature-oblivious urban kid near Bombay, went chasing after vanishing wildernesses in the Himalaya and Western Ghats as a graduate student, and returned to study cities grown up as a reconciliation ecologist.

Madhusudan Katti

An ecologist walks into a suburban backyard… and finds common ground with a sociologist and an anthropologist

I chose to study wildlife biology in my youth because it was easier for me to wander through woods watching (and eventually catching and measuring) birds than to strike up conversations with strangers. I learned how to measure the plants, insects, and other resources birds need in the wild, drawing detailed pictures of their lives in the forests where I spent my Ph.D. years.

Diving into the city to study birds was therefore rather disconcerting for an introverted evolutionary ecologist! It soon became clear that urban bird behavior was shaped by what people do in and to their habitats. And measuring people as the biggest variable to explain bird behavior and distribution is a whole different ballgame than measuring plants or insects. People can be mercurial, and don’t always like being measured in ways I had been trained to do—and their behavior, how they shape their landscapes, is driven by even more complex influences, including cultural, social, institutional, governmental, and market forces that shape decisions in conscious or unconscious ways.

Therefore, when I moved to Fresno, California as a new professor, I first sought out local birding hotspots, and second, collaborators outside my biology department, and off-campus, to help me understand that city’s ecology. Universities don’t make it easy for faculty to reach across disciplinary silos, so one has to commit enough time to build productive collaborations. By the time a grant opportunity arose from the National Science Foundation and US Forest Service under President Obama’s economic stimulus package, I had a team in place to a study how Fresno’s environment would change with the installation of water meters.

While I was able to fill the larger canvas of the whole urban system in broad ecological strokes—where which plants and birds occurred, and how they layered atop patterns in the green-/blue-/grey-scapes of the city—a sociologist filled in important details about underlying socioeconomic gradients, and an anthropologist took us into backyards, talking to homeowners about how and why they chose to have a lawn or other plants, how much and how often they watered them, and what they felt about the birds.

We ended up with a richly detailed socioecological picture of Fresno, depicting details of how people and birds behave in individual homes and yards, and how that fits into the larger patchwork quilt of green spaces and biodiversity across the city. Without my sociologist and anthropologist friends, I wouldn’t have discovered that people wanted lush over-watered lawns in this dry region due to cultural inertia: it was what they knew from the dominant American model home from wetter parts of the country. And this culturally ingrained habit created a lush lawn landscape that kept out too many native bird species. Water metering and drought shifted perceptions enough that we could nudge people towards more waterwise landscaping choices, creating room for more of the local wildlife within the sprawling suburbs of Fresno.

about the writer

Jessica Kavonic

Jess is part of ICLEI’s Cities Biodiversity Center as well as ICLEI Africa’s Resilience team. She has a background in atmospheric science with a more specialised knowledge of climate change and its relationship with a sustainable approach to development.

Jessica Kavonic

Mainstreaming nature into planning in urban Africa: the power of collaboration

Given this, many African cities face a choice: to continue to merely reactto these events, or to address the systematic causes of the loss of natural assets, which counteract the negative effects of such events. Addressing these underlying causes requires scaled action, investment, and collaboration to connect often “siloed” departments and organisations.

Against this backdrop, the Urban Natural Assets for Africa (UNA) programme, among other activities, brings together a wide array of African city stakeholders from different sectors, institutions and organisations in a series of informal learning spaces, to co-explore how to best address these issues.

The benefits of bringing a diverse group of stakeholders together are clear. “Meeting and learning helps presents a complete encompassing picture which triggers action … helping us refocus where we are going and being an eye-opener so that we do not lose direction”, one UNA participant observed after a collaborative learning dialogue. Another participant mentioned that, “if nothing else, this collaborative process provided a great platform for information sharing and learning what others are actually doing. This is an ongoing challenge”.

Increased systems thinking, sharing of knowledge, as well as improved co-ordination and networking are common benefits for co-production. But it is apparent that collaboration also helps foster an improved sense of “togetherness” as it facilitates a greater understanding of others as individuals. One UNA participated said: “I have realised that to work together I need to change my views to be able to meet every [person]. I need to meet others where they are and not where I am … from conversation I see that we all equally contributing to both the solution and the problem. I am not alone”.

Collaboration also offers an opportunity for diverse actors to collectively reflect on and propose solutions to some of the most pressing challenges faced by their cities. One UNA stakeholder noted that, “…hardly do we stop and think about where we are going and if this is the best way to get there. Or that we can have thought of the things we don’t want to happen”.

The UNA learning spaces provide a place for co-exploration of nature-friendly urban planning and development issues with city stakeholders, co-creating the information needed to support policy and practice. However, a major emergent challenge to identifying solutions seems to be the limited ability in unpacking the actual steps needed to take these opportunities forward. Spaces that prioritise dialogue whereby stakeholders effectively unpack the actualmethods for taking discussion forward, analyse howthings can be done differently (especially linked to how certain decisions can be made differently), as well as provide the space for visioning, have proven extremely valuable in collectively overcoming systemic lock-ins.

An emergent principle of the UNA learning spaces is the special emphasis on the actual conversations, the need to follow effective processes, the areas of tension that arise in dialogue and the subtle learnings that occur between participants. It is often these areas of tension that can unlock opportunities for change.

For example, during visionary exercises in Malawi, participants co-developed impact stories for potential futures under plausible climate futures. A major point of tension was whether to include current policy reform and planned interventions in the stories. Participants from one sector were adamant that the future would change based on what they were currently planning to do, and therefore these activities should be included. Whereas other stakeholders were of a differing opinion with one participant mentioning “we are locked into bigger challenges that current interventions will not overcome”.This brought to the fore an important discussion in relation to how African city stakeholders can tackle systemic issues, which would have unlikely happened if an open and collaborative process was not followed. And more importantly, this would have unlikely emerged if there were no areas of tension or differing backgrounds between stakeholders.

As in the biodiversity discourse, which celebrates the role that diversity plays in coping and adapting to changes, so too does collaboration. Different ideas, backgrounds, vulnerabilities and power dynamics, if managed effectively can lead to improved collective action. However, as with any situation differences can result in challenges. One particular challenge that emerges across many ICLEI Africa projects and programmes, is terminology. The same word can mean multiple things depending on the background and perspective in which it is being used, and by whom. This challenge can be overcome, if effectively unpacked early on in the process, avoiding areas of tension that can arise from a misunderstanding of what stakeholders mean and how terms are viewed.

Through its experimentation in co-production, ICLEI Africa and the Cities Biodiversity Center, is effectively establishing new methodologies, tools and learnings for mainstreaming nature into local level planning and decision making processes. Interestingly, a major learninghas been that mainstreaming seems to be limited by confidence. City officials are often looking for the best methods for integration, planning, biodiversity management etc. Collaborative spaces are profound in helping improve confidence in all stakeholders so that they are comfortable that there is no one size fits all and confident in working with the context, resources and methods available to them. In addition, allowing time for diverse stakeholders to engage in a safe space on a mutually important topic is key to building trust and relationships, both of which benefit the longevity of interventions. These subtle and softer skills, which are key to mainstreaming nature into planning, cannot be developed without stakeholder collaboration.

about the writer

Yvonne Lynch

Yvonne is an Urban Greening & Climate Resilience Strategist who works with Royal Commission for Riyadh City.

Yvonne Lynch

There are multiple disciplines of engineers from aeronautical and biomedical, from chemical to mechanical, and everything in between. In a career spanning almost two decades, I’ve worked with all of them, but most continuously with civil engineers. I’m a policy maker with a tertiary education in philosophy and communications, so I’m not exactly the first port of call for a municipal engineering department when they have a problem to solve. We speak different languages. We have different styles of working, different ways of knowing.

As a policy maker, I have always been committed to implementation. It is not enough to design and endorse cutting edge policies and strategies, you must actively drive implementation at every level, otherwise these documents are a waste of time and money. It didn’t take me long to realise that in a city government, you need to win the confidence of the engineers in order to implement sustainable, climate adapted, and ecologically healthy urban spaces.

What I have learned is that change takes time with engineers and that if at first you don’t succeed, then try again. When you come from different ways of knowing, collaboration is not instantaneous or easy. I recall the day I gathered several of my former engineering colleagues together to discuss extreme flooding and sea level rise. It was a hot sweltering summer day in year 13 of Melbourne’s Millennium Drought. I sat with my consultant team and demonstrated our flashy GIS-based flood model, illustrating critical flood scenarios. I was met with the response that we were in the midst of drought, this was not a priority matter. I tried to explain that our Climate Adaptation Strategy said we will experience drought and extreme flooding more frequently and simultaneously. By the end of our meeting, almost prophetically, the city had been unexpectedly flooded in the space of an hour. There were people swimming down Flinders Street.

Floods! Fabulous! What an endorsement for immediate action to progress this work, right?

Wrong. In fact, it took many more months and years to advance the municipal approach to climate-adapted flood management. And rightly so, because dealing with the big issues is rarely immediate. And changing the approach to municipal design, engineering and management is no overnight matter and nor is it something that can be driven by an evidence-based scenarios model or a single policy, plan or person!

Transformational city change takes time and requires the involvement of hundreds of municipal officers and many leaders. But when the engineers get involved, the innovation picks up pace and the magic begins to happen. I’ve seen first attempts at permeable paving quite literally sink in the ground, and I’ve seen engineers solve the problem. I’ve marvelled at largescale stormwater harvesting infrastructures and watched the engineers make them work when problems arose.

I’ve learned the key to collaboration with engineers is taking the time to fully explore the critical issues together. Its also about starting the work together from conception and not engaging them only at the point of implementation. The second time I developed a flood model, the engineers collaborated from the outset and owned the final product. And, probably the most important element of collaboration is acknowledgement. So often a lead work area in a city government can garner the attention for success, but the work always involves multiple parties. Highlighting those players and saying thank you is critical, and so is asking: what are we going to do next?

about the writer

Mary Mattingly

Mary Mattingly creates sculptural ecosystems in urban spaces. Mary Mattingly’s work has been exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum, International Center of Photography, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de la Habana, Storm King, the Bronx Museum of the Arts, and the Palais de Tokyo.

Mary Mattingly and Lonny Grafman

Through being able to collaborate with Lonny, I’ve learned a number of practical skills, from plumbing a dry composting toilet, grease traps, and gutters to setting up solar systems. Every day, I utilize other skills I learned through working with Lonny, including modeling criteria for small and large projects and mapping team assets. Without having the formal background, I’ve been brought into his world and am now able to think more like an engineer, which has helped me immensely in other endeavors. Lonny has also taught me how to communicate more clearly, be more self-assured and therefore convincing. Most of all, Lonny has taught me that meeting new people and then finding common ground is a necessity.

Lonny: When I received that random late-night call in 2008, I was a little skeptical. The scale was epic, the need to inspire people regarding climate change was palpable, and the tone was a mixture of apocalyptic and whimsical. At the same time, this project seemed like one of those things that people talk about and never do.

Through my conversations with Mary, I quickly realized how serious she was and how definitively she was going to make this happen…so I jumped on board.

The projects I generally work on are more directly practical—e.g. safe drinking water, clean energy, local entrepreneurship, sustainable construction, etc. While these projects may have an artistic element, the main goals are more obvious. In these projects, it is easy for me to know what is a necessity and what can be changed. In an epic art project, it is much harder to know. Watching Mary articulate her grand vision and weave in multiple cocreators with their own visions was edifying. Yet, if I had to pick just one thing I learned deeply working with Mary, I would pick whimsy.

Whimsy. I am sure that is not how Mary would describe it, but it is how it seems to me. I have learned deeply how whimsy matters. The better engineered something is, the more visitors, users, and stakeholders will enjoy the more whimsical aspects. The fanciful, imaginative, and even the evanescent serve to inspire. I often think back to my early thinking on the Waterpod. I was attempting to calculate the embedded energy of every part of the barge in order to balance our impacts…and yet somehow, I forgot to calculate in the impacts on the visitors and what they would end up changing in their lives. We had 200,000 in person visitors. Anecdotally most left inspired. If even a small fraction of these visitors made change, the investment was more than worth it.

about the writer

Lonny Grafman

Lonny Grafman is an Instructor at Humboldt State University; the founder of the Practivistas summer abroad, full immersion, resilient community technology program; the project manager of the epi-apocalyptic city art project Swale; the Chief Product Officer of Nexi; the managing director of BlueTechValley North Coast; and the President of the Appropedia Foundation, sharing knowledge to build rich, sustainable lives.

about the writer

Brian McGrath

Brian McGrath is Professor of Urban Design at Parsons School of Design at The New School and Associate Director of the Tishman Center for Environment and Design where he leads the Infrastructure, Design and Justice Lab. The focus of his work is the architecture of urban adaptation and change from social justice and ecological resilience perspectives.

Brian McGrath

I studied architecture as an undergraduate and graduate student within stand-alone professional schools within liberal arts universities. These schools awarded degrees that conform with national and state licensing structures, but emphasized architecture as an inherently cultural act that engages in the collaborative construction of cities according to collective social norms and aspirations. The best way to understand any culture is to visit its cities and to be enveloped in the life-worlds produced by architecture and building. Art, literature, and all forms of cultural production as well as the various forms of urban social life constitute a type of collaborative project with the design and building of the city as a collective artifact. During the European Renaissance and Enlightenment, architecture was placed at the center of this collaborative enterprise, and therefore served as both the common narrative and the arena for the exertion of power. This can be seen as a hierarchical collaborative model, where the discipline of architecture was created in order for a prince, religious leader, wealthy individual, or civic group to arrive at a physical structuring of both the city as a whole, and various institutions, public spaces, and private buildings within it. Cities are inexhaustible texts from which to read or decipher the power structure, ethics and values of a society, in other words, how they collaborate or not.

As a recent graduate undertaking a career as an architect in Lower Manhattan in the 1980s, the injustice of the hierarchical Eurocentric architectural model became clear. Recent struggles for civil rights, social equity, feminism, and queer theory are just a few of the social movements that provided more democratic and just models of collaboration. I lived within a milieu that was rich in collaborative experiments such as homesteading in vacant buildings, green gorillas seed bombing vacant lots, community gardeners, bicycle activists, independent art, poetry and performance groups, community land trusts, community housing organizations, and AIDS activism. Collaboration under this activist model questioned the older patriarchal and colonial models that the U.S. had always tried to import as forms of cultural legitimacy from European sources. Unfortunately these grass roots organizations were ill-equipped to counter the economic and political restructuring of New York City following its near fiscal default in the 1970s. As city officials became more invested in economic development rather than social welfare, architects were quick to provide a cultural veneer and narrative for displacement, gentrification and the commodification of the city. A corporate model of collaboration creates a professional hierarchy of a client, either public or private, a lead designer for a project, with various vertical tiers of consultants, depending on the scale and complexity of the project.

With each passing decade preceding and following the new millennium, new developments in digital technology. The development of modeling software, wide access to the internet, and hand held links to social media invited new models of collaboration and with the widening of access to the tools that created the possibility of a return to the more radical non-hierarchical collaborative models developed in the ‘60s and ‘70s, culminating in Occupy Wall Street in 2011. New technology formed the basis of multiple experiments in urban design collaboration that I undertook as a teacher and practitioner in urban design. One project, Manhattan Timeformations, celebrated the new millennium with an interactive on-line data base that allows viewers to understand the historical formation of New York’s two central business districts. The publicly funded project with the Skyscraper Museum involved multiple public forums in the creation of the digital model in order to provide an easy user interface. The project has had a wide internet audience and after it was published in WIRED magazine and I was approached by three principal investigators of the Baltimore Ecosystem Study (BES) who were experimenting in GIS software and time based mapping of longitudinal research. As one of two urban sites as part of the National Science Foundation’s Long Term Ecological Research program, the research project brings social and biophysical scientists together in collaborative research projects, driven by the accumulation of data over long time periods, This collaborative approach to research has significantly enriched the understand of the Baltimore region as an urban ecosystem. After 15 years with BES, I have become convinced of the need for new collaborative models around the shift in the cultural narrative for cites from the architecture to the ecology of cities. These models are multi-scalar and multi-actor, including the essential balancing of non-human and human actors. Important is that this new collaborative model is not about green space in the city, but a cultural metaphor for the ecology of and for the city.

about the writer

Ragene Palma

Ragene Palma is a Filipino urbanist currently studying International Planning at the University of Westminster, London, as a Chevening scholar. Follow her work at littlemissurbanite.com.

Ragene Palma

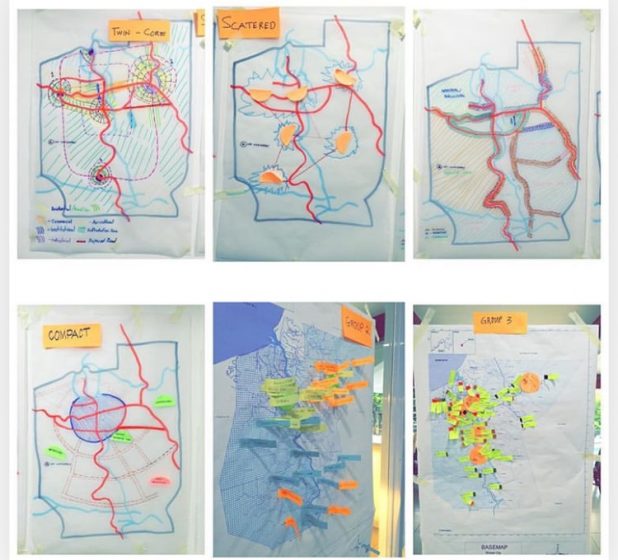

While I am fond of sharing many experiences on planning, let me write about my work under the UN HABITAT Philippines. In 2015, I became part of the team that worked on the Achieving Sustainable Urban Development (ASUD) Programme. As part of the strategy to approach planned city extensions holistically, the program used the model of enhancing governance, financing, and economic development to ensure how leadership, implementing ability of plans, and economic progress could move together.

I was tasked to work on the local economic development of select cities. In doing so, I had to work closely with all economic departments of the government and groups within civil society. The sectors involved included agriculture and fisheries, trade, entrepreneurship, and business development. In conducting primary research, I worked with farmers and fisherfolk, business owners, and entrepreneurs. In conducting secondary research, I worked with local government departments, including trade and tourism. I also conducted research with special sectors, including the youth, to understand issues on schooling courses, preferred industries, and access to employment; social welfare groups, to understand issues on migration in and out of the city; and people’s organizations that could provide perspectives on informal markets.

The knowledge of each of these sectors was vital to understanding the local economy. The assessments and strategy development spanned from defining the cities’ strengths and capacities (including skills, production, income) to aligning local economic growth to the planned city extension while sustaining the current economic activities.

The knowledge of each of these sectors was vital to understanding the local economy. The assessments and strategy development spanned from defining the cities’ strengths and capacities (including skills, production, income) to aligning local economic growth to the planned city extension while sustaining the current economic activities.

Another key collaboration in the program was the close work of environmental planning and geography. In creating strategies for local economic development, the spatial component was of utmost importance, because of how it helped direct the workability of improved value chains and linkages within industries, and the viability of connecting the city extensions.

While there were many other collaborations across disciplines and ways of knowing in the ASUD Programme, which were equally valuable to city and environmental planning, what I shared could be an overview of the interphases in economic planning. Valuing specialized, local knowledge through collaboration enhances one’s work through added value, provides a change of perspective in a profession, and challenges viewpoints to become truly holistic.

about the writer

Diane Pataki

Diane Pataki is a Professor of Biological Sciences, an Adjunct Professor of City & Metropolitan Planning, and Associate Vice President for Research at the University of Utah. She studies the role of urban landscaping and forestry in the socioecology of cities.]

Diane Pataki

Stephanie and I have virtually nothing in common in terms of disciplinary background. I am a quantitative ecosystem scientist who has spent my career making physiological and physical measurements of the urban environment, placing probes in trees and soils, measuring isotopes of various elements, and applying statistical and computational models of plant-atmosphere interactions. Stephanie has a Ph.D. in urban planning and has worked in environmental justice, land use politics, and urban governance. But over the last 14 years or so, our collaborative work on the role of vegetation and greenspace in cities has resulted in many of my most exciting, gratifying, and simply fun projects.

We met years ago through a mutual colleague (the path-breaking soil scientist Susan Trumbore), who invited Stephanie to give a lecture on urban ecosystem services. Years ahead of her time, Stephanie presciently saw the many emerging challenges in feasibly designing, planning, and managing cities to accommodate nature in different ways. My research at the time, and still today, was focused on measuring ecosystem services, and so a collaboration was born. However, I’ve had many, many interdisciplinary collaborations over the years, and this one turned out to be special. This roundtable has given me the opportunity to ponder why

Interdisciplinary collaborations between ecologists and social scientists were popularized at least 20 years ago, when funding agencies such as the U.S. National Science Foundation incentivized the formation of research teams that could take on complex environmental challenges, such as Biocomplexity in the Environment. As part of one of those early teams, I met social scientists who specialized in studying interdisciplinary team dynamics. From them I learned that one of the key ingredients that can make or break interdisciplinary collaborations is respect. Teams that breakdown or fail to coalesce are often composed of one or more members who feel their expertise and contributions are not truly respected by their collaborators. Conversely, strong teams respect the value of each other’s disciplines, expertise, and accomplishments.

Although I had a pretty poor understanding of the qualitative social sciences when I began to collaborate with Stephanie, I immediately respectedher clear thinking, sharp assessments of environmental and social issues, and creative solutions to the persistent problems that plague modern cities. She also conveyed a deep understanding and appreciation for the uncertainties about the functioning of designed landscapes that characterize urban ecology. Together, we have now jointly unraveled many interesting findings about fundamental relationships between people and urban nature that will, we hope, help us better steward urban landscapes and human-non-human interactions in the future.

It’s impossible to know exactly what would have happened if this collaboration had not materialized, but I’m quite sure I would have learned far less about cities and their human and non-human inhabitants. Is it possible to really understand the ecology of urban plants without studying the reasons, the history, and the goals of the people that planted them? Can we adequately plan and manage urban greenspace without a deep knowledge of how people and nature interact? For me, the answer is clearly no.

Notably, it was Stephanie who introduced me to TNOC and its amazing community (you can read our first joint contributionhere). These days, our work is so intertwined that some people, amazingly, have asked me if we come from exactly the same discipline. Certainly we don’t, but I hope it’s true that in the end we played a part in developing the “transdiscipline” that studies the interface of people and urban nature. And that is probably the best collaborative outcome of all.

Many thanks to Stephanie and our other friends and colleagues. Onward!

about the writer

Wilson Ramirez Hernandez

Wilson Ramirez Hernandez Ph.D., is a Senior Researcher (Coordinator) in the Alexander von Humboldt Institute, is the coordinator of the territorial management program, he is Lead Author in the IPBES objective 3bi (land degradation and restoration), and he is working in urban restoration and urban sustainable indicators.

Wilson Ramirez

At the beginning I felt a kind of short-circuit between the classical scientific language and the decision making and territorial management language used in the mayor´s team. The good point is after a couple of months, my team and I understood that we were discussing the same concerns, but with different words. After that experience, I´ve decided to include an expert in the interface of science and policy into my regular team, in order to establish clearer connections and more relevant interpretations of environmental information for policy stakeholders.

Recently, a new urban sustainability project has begun, and I feel confident about the new results. As a conclusion, I believe that if we want to be more impactful in our work as scientists, especially in urban contexts, the more diverse the team is, the better results you will have. This is a special conclusion mainly for science research institutes, where the natural way of working is among only a few colleagues who share the same expertise.

about the writer

Bruce Roll

Bruce is the Director of Watershed Management for Clean Water Services (www.cleanwaterservices.org) and the nonprofit Clean Water Institute (CWI) in Hillsboro, Oregon.

Bruce Roll

In 2005, CWS received one of USA’s first discharge permits that allows for water quality trading in the Tualatin River Watershed. This permit allowed CWS to invest in riparian restoration instead of costly hard infrastructure, such as water chillers estimated to cost over 150 million dollars. At this time, local governments were witnessing two huge watershed stressors: climate change and prolific urbanization. Creating a resilient watershed able to survive these challenges would require a scale of action far beyond the wheel house of my utility, and demonstrated a need to find transformational partners capable of bringing additional resources to the table.

As CWS began to implement its new riparian restoration program, it became clear that we would need to think outside the box, find new partners, and create a new language. A language that engaged and inspired. Utilities are very good at planning, modeling, and constructing hard infrastructure, but often struggle when designing projects for Mother Nature. If we had used the classic utility model, it would have meant paying for costly access easements, minimizing distractions like parks and trails, thinking of mitigation as a one-time transaction, and pursing the easiest compliance outcome. That approach would have also resulted in high project costs and, most likely, an inability to achieve landscape-scale results. Wanting to avoid this inefficient approach, I sought the support of parks and open space groups that had land but limited resources for restoration or maintenance.

I learned very quickly that words like mitigation, compliance, discharge permit, and trading were part of my utility jargon, but certainly did not inspire or engage parks and open space groups. They looked at me like I was a one-eyed monster from the sewage lagoon trying to pull a fast one. Luckily, I was able to step back, stand in their shoes, and reengage with a new vocabulary that talked about values like watershed resilience, biodiversity, stewardship, cultural heritage, sustainable economies, recreation and human health. It was truly amazing how quickly we went from “No” to “Go, Go, Go”. Now, 15 years later, we have found a home for 10 million native plants, and restored 150 river miles across 25,000 plus acres in the Tualatin River Watershed (www.jointreeforall.org). What started as a utility’s regulatory compliance opportunity is now a group of over 30 partners working together to create a healthy and resilient watershed.

What I find most inspiring about this story is what we are able to achieve when we share a common set of values and inspiring language. This approach forced me and CWS to move from transactional to transformative partnerships. In many cases it took years of hard work to create the transformative partnerships that were necessary to move to scale, but when I look at the 700 plus projects that we accomplished together, I see that it was all well worth it.

about the writer

David Simon

David Simon is Professor of Development Geography at Royal Holloway, University of London and until December 2019 was also Director of Mistra Urban Futures, an international research centre on sustainable cities based at Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden.

David Simon

Social scientist and local authority official and consultant

Mistra Urban Futures is an international research centre on urban sustainability that experiments with various forms of transdisciplinary co-design/-creation or -production methodologies in formal transdisciplinary institutional partnerships. In this sense, transdisciplinarity refers to academic and various policy and practice stakeholders working together into research partnerships—as distinct from interdisciplinarity, which refers to people from different academic disciplines working together.

As a partner in the Campaign for an Urban Sustainable Development Goal from 2014, I realised the potential value of using the four cities where Mistra Urban Futures at that stage had transdisciplinary research platforms to test the draft targets and indicators for what became Sustainable Development Goal 11 (SDG 11, the urban goal). Despite the great diversity of skills and experience within the Campaign, debate and dialogue could only get us so far and to be able to provide feedback to the UN statistical team on the basis of real-world testing would be a huge advantage. With additional funding, we then undertook an intensive 3-month pilot project in early-mid-2015 to work with the local authorities in our four platforms (Gothenburg (Sweden), Greater Manchester (UK), Cape Town (South Africa), and Kisumu (Kenya))–and we added Bangalore (India), to provide an almost-megacity in Asia for even greater diversity of conditions and operational challenges.

The challenges of setting up and running the experiment were considerable, not least in terms of the short timeframe but also all the well-known differences of priorities, operational protocols and procedures, budgetary constraints and staff availability. The project was designed centrally but operationalised and implemented locally by each of our city platforms and the team in Bangalore at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements. The example here focuses on Cape Town, but each city case study threw up specific challenges.

The immediate issue in Cape Town was that the formal partnership underpinning the research platform was between the academic host and partner, the African Centre for Cities at the University of Cape Town, and one particular department in the City of Cape Town (i.e. the municipality). For a combination of the above reasons, the head of that municipal department was not well disposed to participation in the project or even the idea of developing a new set of targets and indicators, because South African metropolitan authorities were at that time overwhelmed with performance and compliance demands from central government in the form of overlapping indicator sets.

Participation in the project depended on finding a different path. The leadership of the Cape Town platform used personal connections to discuss the proposal more widely in the municipality. Fortunately, the head of one integrative department saw the point of the exercise and also the value to the City of having a “dry run” of activities on which it would have to report annually from 2016-30 in any event. She became the crucial institutional “champion”, along with a former municipal employee and at that time a consultant working with the national Treasury (finance ministry) to harmonise reporting indicators for metropolitan authorities.

Not only did the partnership work effectively because of these champions but because our team was able to generate synergies of interest among the participating partners that benefited all concerned, as well as contributing to a successful project that helped refine the final targets and indicators of what became SDG 11. It enhanced the partnership’s existing relations of trust and has led to an extremely fruitful ongoing partnership implementing a longer term follow-up project on how the City is engaging with the SDGs and New Urban Agenda.

For further details, see the following Open Access papers:

D. Simon, H. Arfvidsson, G. Anand, A. Bazaaz, G. Fenna, K. Foster, G. Jain, S. Hansson, L. Marix Evans, N. Moodley, C. Nyambuga, M. Oloko, D. Chandi Ombara, Z. Patel, B. Perry, N. Primo, A. Revi, B. van Niekerk, A. Wharton and C. Wright (2016) ‘Developing and testing the Urban Sustainable Development Goal’s targets and indicators – a five-city study’, Environment and Urbanization28(1), pp. 49-63 (my contribution 30%), http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956247815619865.

Z. Patel, S. Greyling, D. Simon, H. Arfvidsson,N. Moodley, N. Primo and C. Wright, (2017) ‘Local responses to global sustainability agendas: learning from experimenting with the urban Sustainable Development Goal in Cape Town’, Sustainability Science 12(5), pp. 785-797 DOI 10.1007/s11625-017-0500-y.

about the writer

Dimitra Xidous

Dimitra Xidous is a Research Fellow in TrinityHaus, a research centre in Trinity College Dublin’s School of Engineering that focuses on co-creation and the intersection between the built environment, health, wellbeing inclusion, climate action and sustainability. She is an Executive Editor of SPROUT, an eco-urban poetry journal, run in partnership with The Nature of Cities.

Dimitra Xidous

The collaboration between myself and Ria has been slow, and incredibly fulfilling; to have taken our mothers as starting points from which to examine otherness, language, and absence (to list only a few of the themes floating up to the surface) was as much an ambitious as well as a loving endeavour. In between ambition (our creative drives) and love (for our mothers) lies the big challenge: how to ensure, via our chosen mediums, we meet the goals we have set out, both with respect to engaging across our disciplines (the process of collaboration), and the project itself, as a stand-alone art piece (the product of collaboration).

For me, the challenge manifested itself in two ways. Firstly, I discovered I could not “write” Ria’s mother (I don’t know her, will never know her). This not-knowing is a constraint I had not anticipated I would need to learn to work within; it has forced me to write differently. Poems which reference Ria’s mother are built from details Ria has told me about her; fragments of memories of when Ria was a little girl. In the beginning, I thought my writing for the project would be a root (act like one), something to keep me steady – a root to root me in time and in place. A foundation. A narrative. In some way, and because of this rootedness, I thought my poetic acts of re(membering) would pull the fragments to whole, again—for both her mother, and mine. Instead, I find myself writing poems that mirror the prints Ria is producing; this was not my original intention, and while there is a narrative emerging, it is not the one I had anticipated, or imagined, or wanted (don’t ask me to describe what I wanted; I don’t remember anymore). But: I am working with, not against, the constraint because it is showing me something I have (always) felt to be true of collaboration: it is an act of translation. We are speaking to each other, across poetry and print, and coming to (new) terms. This has been good.