Since I was invited to start writing about biocultural diversity for The Nature of Cities in 2015, there have been a number of developments in both policymaking processes related to biocultural diversity and, recently, to the concept itself. Some of these developments have happened around the Fourteenth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD COP 14) that took place in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt in late 2018. With the end of COP, now seems a good time to take stock and update readers on what has been happening and what we can look forward to as we near the end of the UN Decade on Biodiversity 2011-2020, particularly as it relates to urban biodiversity.

For those readers who may be unclear about the term “biocultural diversity”—you’re not alone. For reasons that I will touch on in this essay, it is increasingly difficult to define the term and equally difficult to understand its implications for policymaking. Simply put, biocultural diversity refers to the links between biodiversity and cultural diversity. Biodiversity, according to the CBD, means “the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part”. This definition is complicated by the fact that biodiversity itself is measurable in different ways depending on scale and other factors—whether it means total number of species in the world, species per hectare, or others; a complication that the CBD addresses by including all of these perspectives. Cultural diversity, for its part, can refer to a diversity of different cultures (for the purposes of this essay, I will refer to this understanding as “diversity-of-cultures”), or a diversity of elements within a single culture (“diversity-within-a-culture”; see previous parenthesis). Putting these two complex ideas together adds another degree of difficulty, with most, in my experience, choosing instead to gloss over the issue by referring to it obliquely through discussion of, for example, “the links between biological and cultural diversity” as adopted by the CBD and UNESCO when they were unable to land on a definition.

In any case, some research has shown that higher cultural diversity may be found in places where there is a higher level of biodiversity, borne out by findings that higher linguistic diversity exists in areas with higher biodiversity, indicating that more diverse nature and more diverse culture go together. In terms of policymaking, particularly in processes related to biodiversity such as the CBD, this comes with the implication that policies that encourage the conservation of elements of cultural diversity will enhance the conservation of biodiversity.

With this background, there has been movement in recent years towards incorporation of, or at least respect for, cultural diversity in the CBD’s ongoing policymaking processes. Much of this movement has been related to Article 8(j) of the Convention, which calls for Parties to respect innovations and practices of indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs), with the result that biocultural diversity under the CBD is closer to diversity-of-cultures, than diversity-within-a-culture. A major development was the establishment of the CBD Secretariat and UNESCO’s Joint Programme on the Links between Biological and Cultural Diversity. While the Joint Programme has been faced with a shortage of funding and institutional capacity, its proponents have been involved in all of the events and processes mentioned here either directly as organizers or participants.

One of my previous TNOC articles focused on some of the early events, including the 1st European Conference on Biocultural Diversity held in Florence in 2014, which resulted in the “Florence Declaration on the Links between Biological and Cultural Diversity”, and an International Symposium on Biocultural Diversity in Kanazawa, Japan in 2015 that launched a proposed model for an urban biocultural diversity region. Both of these were held in and largely organized by countries of the so-called developed world, and they present a vision of biocultural diversity more as diversity-within-a-culture, somewhat different from subsequent CBD processes that have tended to focus on the diversity-of-cultures of IPLCs often in the Global South.

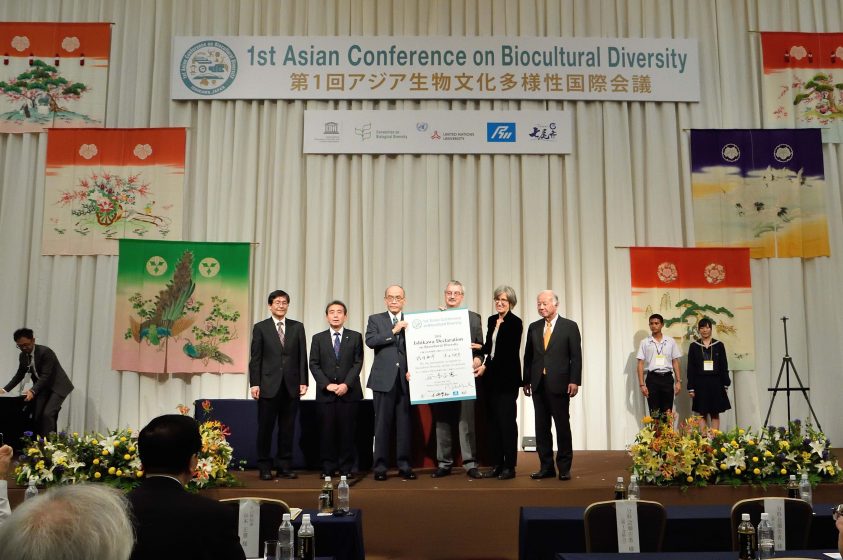

The 1st Asian Conference on Biocultural Diversity was held 27 to 29 October 2016 in Kanazawa Prefecture, Japan, following-up on both the European Conference and the workshop in Ishikawa, and resulting in the adoption of the “Ishikawa Declaration on Biocultural Diversity”. The Declaration itself is fairly anodyne, with participants promising to further the cause of biocultural diversity in various ways, but includes an annex with recommendations that point towards the diversity-of-cultures model, such as recommendations to “learn from indigenous peoples, local and traditional communities living sustainable lifestyles” and to “use traditional and local calendars to reconnect with Nature and the seasons to promote understanding of cultural, cultivation and life-cycles”. Like the Florence Declaration, the Ishikawa Declaration was not produced at an event that was part of CBD processes, although the CBD Secretariat and others active in CBD processes were involved, and it was disseminated at CBD events.

A weekend event on “Contribution of the links between Biological and Cultural Diversity, Community Conservation and Customary Sustainable Use to the Implementation of the Strategic Plan on Biodiversity 2011-2020 and the Aichi Targets” was held during CBD COP 12in Pyeongchang in 2014, which turned out to be a prelude to what may be a new tradition, holding “summits” related to biocultural diversity during COP meetings.

The Múuch’tambal Summit was held 9 to 11 December 2016, the middle weekend during the two weeks of CBD COP 13in Cancun, Mexico. This event was more heavily focused on indigenous peoples and Article 8(j) issues under the CBD than the Florence and Ishikawa events, and resulted in another Declaration, the titled “Mainstreaming the contribution of Traditional Knowledge, Innovations and Practices across Agriculture, Fisheries, Forestry and Tourism Sectors for the conservation and sustainable use of Biodiversity for Well-being” which, like other Declarations produced by conferences, contains rather general statements and recommendations, in this case with a heavy IPLCs focus. It does, however, represent a kind of development in that it was produced from an event organized specifically in CBD processes, and was included by the COP as an information document in official policymaking processes. While it does not significantly affect the direction of the CBD, this shows a greater integration and appreciation for these developments in international policymaking.

Between this and the following COP, some smaller related events were held. The United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability’s Operating Unit Ishikawa/Kanazawa (UNU-IAS OUIK) in Japan organized a series of international forums to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the 2016 Asian Conference. This consisted of two events, the first of which was held on 4 October 2017 on “Biocultural diversity & satoyama: Efforts towards societies in harmony with nature around the world” and dealt largely with issues in Japan, as well as globally in terms of the Satoyama Initiative. The second was on 15 October 2017, titled “Preserving Biocultural Diversity for Future Generations: Partnership of East Asian Countries”, focusing on IUCN work in China, South Korea, and Japan.

On 21 and 22 April 2018 a meeting related to the Joint Programme, the “Action Group on Knowledge Systems and Indicators of Wellbeing”, was held by the Center for Biodiversity & Conservation of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. This meeting was held during the weekend in between two weeks of the meeting of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and again prominently featured issues related to IPLCs. The Action Group is part of an effort to create action groups under the Joint Programme to explore various issues, although to my knowledge this is the only action group to hold a meeting to date. In any case, the outcomes of the meeting include the creation of an online directory of resources related to biocultural indicators of wellbeing, in addition to a report submitted to the CBD. While these are promising and useful contributions, it is not entirely clear to this author what the next steps for this action group will be. Readers are encouraged to consider any ways you might be able to get involved.

This brings us to the most recent major event in this series, the weekend summit held between the two weeks of CBD COP 14 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt from 22 to 24 November 2018. This time it was called the “Nature-Culture Summit”, seemingly removing the term “biocultural diversity” and anything like “links between biological and cultural diversity”. Again, the summit produced a Declaration, the “Sharm El-Sheikh Declaration on Nature and Culture”. This one again mostly reaffirms many of the elements from earlier declarations and meetings, but is significant for at least two reasons: first, as mentioned above, it marks what may be the beginning of a new chapter in which “biocultural diversity” or “links between biological and cultural diversity” are now “a rapprochement of Nature and Culture in the post-2020 era”; and second, it calls for the establishment of what is planned to be a “multi-partner International Nature-Culture Alliance” to be launched at CBD COP 15 in 2020 in China. In fact, the summit was conceived as a kind of scoping or preparatory event for the launch of this Alliance.

So, what do these events, declarations, and related activities tell us about some of the directions that biocultural diversity has been moving in over the past few years, and what does this say about the state and future of biocultural diversity?

For one thing, and this may turn out to be the most important for the overall future of biocultural diversity, this last development indicates that the terminology may be changing from biocultural diversity to “Nature and Culture”. Not only is “biocultural” not presented as a single unitary concept, but actually the word “diversity” is gone, likely in part an attempt to reduce jargon that may not be commonly understood. This makes sense in that biocultural diversity is obscure enough that, as mentioned above, even those working directly with it have differing and sometimes-unclear ideas of what it actually refers to. It remains to be seen, though, if this represents a move towards Nature and Culture as two separate things that need an Alliance, and away from what had been an emerging concept of a single entity called biocultural diversity. There had been a sense that biocultural diversity was something somehow greater than the sum of biodiversity and cultural diversity, but would the same be true of a “rapprochement between Nature and Culture”? Biocultural diversity per seis not dead as a field of study, as a number of scholars have been working on the concept for years and will undoubtedly continue to do so, but if current trends prevail, it may not be a big factor in CBD circles. In any case, the work plan for the Nature-Culture Alliance is still being developed. It remains to be seen what, if any, effect it will have on policymaking post-2020.

Finally, and to finally get to the discourse on The Nature Of Cities, what all this means for urban diversity is also up in the air. The Ishikawa-Kanazawa model was proposed in 2016 as an idea for biocultural diversity related to the UNESCO Creative Cities Network, but it is not clear where the process is going if anywhere, and its general conception of a diversity-within-a-culture and explicit grounding in “biocultural diversity” may need to be reconsidered in light of trends described here towards diversity-of-cultures and “Nature and Culture”.

The term “biodiversity”, at whatever scale it is being used, indicates a large number of species present, while “nature” implies plants, animals, ecosystems, etc. in some sort of natural state—as the Cambridge Dictionary puts it, “all the animals and plants in the world and all the features, forces, and processes that exist or happen independently of people” (emphasis mine). As has been discussed on TNOC many times in the past, cities can be hotbeds for a number of kinds of biodiversity—such as a gathering point for many, not necessarily native, species in gardens, parks, and homes, or for urban flora and fauna uniquely adapted to the urban environment—but it is less obvious whether we can consider these forms of urban biodiversity as “Nature” when they are not in a state where they exist or happen independently of people.

In any case, it is clear that the upcoming “Nature-Culture Alliance”—even assuming that it represents the future of biocultural diversity in CBD processes—is very much in the process of developing its future direction and activities, including how it may come to consider its core concepts like “Nature” and “Culture”. I am sure I don’t need to make a case for the importance of urban biodiversity to an audience of The Nature Of Cities readers, so let me just conclude by saying that those involved in, or interested in being involved in all of this are encouraged to take part and consider how such an alliance could be nudged toward a direction where urban biodiversity, perhaps urban biocultural diversity, could continue to gain greater recognition in this and other international policymaking processes.

William Dunbar

Tokyo

Dear Sir/Madam

I am looking further information on nature and culture associated events. Also programme of work on 2020.

Thanks with regards

Kamal Kumar Rai

Nepal

Dear Sir/Madam

Nature and Culture Alliance is very important initiative. As a member of IPs and biodiversity professional wish to continue on this regards

Kamal Kumr Rai

indigenous Knowledge and Peoples Network

Society for Wetland Biodiversity Conservation Nepal

Himalayan Folklore

Po Box 12476

Kathmandu

Nepal

There is hope for the future of Biocultural Diversity, and the efforts for example of UNESCO in methods of cultural revitalization through the Creative Cities Network is a great first step. At the same time, there needs to be a more consistent effort in bringing awareness to the intergenerational knowledge of natural systems that cultural appropriation has all but extirpated.

The problem is that this is more than a one-step process, and we are in danger of losing the ability to learn this critical knowledge in the first place. There has to be a more widespread language reawakening effort to preserve the numerous severely threatened indigenous languages, as continually more of this native dialect, and with it cultural artifacts are lost. At the end of the day, Biocultural Diversity takes a cumulative effort that begins through the survival of cultures, and the ability to even learn this traditional ecological knowledge in the first place. If we don’t put more efforts forth in preventing more endangered and extinct languages, we stand to face that much more difficulty in our endeavors.