John Dingell was frequently called the “Lion of the U.S. Congress” because his passion for conservation of natural resources and outdoor recreation coupled with keen legislative skills, and unwavering support for public service led him to great success as the architect behind most environmental legislation in the U.S.

But he was most endeared as a conservation hero.

John Dingell, Jr. learned to be an outdoorsman and public servant from his father—Congressman John D. Dingell, Sr. Upon the death of John Dingell, Sr. on September 19, 1955, John Dingell, Jr. was elected by special election to fill his father’s seat on December 13, 1955 at the age of 29.

Throughout his life Dingell was a congressional page, a park ranger, a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Army during World War II, an assistant county prosecutor, and always a lover of the great outdoors. He grew up fishing and hunting in and along the Detroit River and western Lake Erie and saw first-hand what we, as society, were doing to pollute our rivers and lakes. Dingell’s love of the outdoors and his passion for public service led him to champion clean water and conservation in Washington, D.C.

Dingell was a master of legislative deal-making. For 14 years he served as chairman of the powerful House Energy and Commerce Committee, which oversees industries from banking and energy to health care and the environment. He frequently was called the “Lion of the U.S. Congress” because of both his influence and effectiveness.

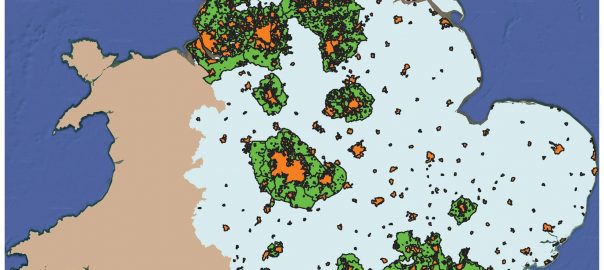

His environmental and conservation accomplishments as a legislator include the Ocean Dumping Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, and more. He served on the Merchant Marine Fisheries Committee that gave him freedom to work on big issues that he really cared about. He also served from 1969-2014 on the Migratory Bird Conservation Committee where he worked in a bipartisan fashion to purchase lands for the National Wildlife Refuge System—a 150 million-acre array representing the world’s largest network of lands and waters set aside for wildlife conservation and to increase funding for Land and Water Conservation Fund and the North American Wetlands Conservation Act.

Dingell’s passion for conservation of natural resources and outdoor recreation, keen legislative skills, and unwavering support for public service were key factors that made him so successful. The significance of some of his major legislative accomplishments is worth highlighting.

Dingell wrote the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act, known as NEPA, which requires federal agencies to consider the environmental consequences of developmental projects before they are constructed. This act is sometimes referred to as the “Magna Carta” of environmental law, and more than 100 nations around the world have enacted national environmental policies modeled after it.

He played a vital role in passing the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act that provides an integrated approach to protection of marine mammals and was significant because it was the first legislation to adopt an ecosystem approach to natural resource management and conservation. Today, the ecosystem approach is widely accepted throughout the world.

Dingell was the architect of the 1972 Clean Water Act which has helped cleanup and protect waterways from pollution. Today, the Clean Water Act is credited with significantly reducing pollutant inputs that has led to ecological revival of many waterways, although more efforts are needed. This act has also served as model legislation for numerous countries to regulate the discharge of pollutants to surface waters to restore and maintain their chemical, physical, and biological integrity.

He authored the 1973 Endangered Species Act which made the U.S. the first country in the world to make human-caused extinction of other species illegal and today is credited with saving hundreds of plants and animals from extinction, including the Bald Eagle, Peregrine Falcon, Green Sea Turtle, Humpback Whale, Southern Sea Otter, El Segundo Blue Butterfly, Robbins’ Cinquefoil, American Alligator, Brown Pelican, and more.

Dingell authored the 2001 Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge Establishment Act to not only protect over 100 species of fish and over 350 species of birds in the heart of the North American Great Lakes, but to demonstrate how to use public-private partnerships to build an urban refuge that prioritizes bringing conservation to cities and makes nature part of everyday urban life. He wanted to protect his favorite fishing and hunting grounds from his youth and do it in a fashion that inspires the next generation of conservationists in urban areas because that is where 80% of all U.S. and Canadian citizens live. Clearly, this concept of an urban refuge that inspires the next generation of conservationists is consistent with the goals and transformative ideas of The Nature of Cities.

Today, the waters of the United States are cleaner, the birds, fish, and other species are safer, and all of us have national wildlife refuges and national parks where we can recreate, reflect, spark a sense of wonder, learn about sustainability, and pass on a conservation ethic to the next generation—largely because of John Dingell.

John Hartig

Detroit

Leave a Reply