The Philippines has repeatedly taken blows causing environmental degradation. Last month, a dead whale was found with 40 kilograms of plastic in its stomach. In the same month, Metro Manila experienced a water crisis, affecting millions, and increasing risks in sanitation and waste management. In relation to this, protests have been held to oppose a planned dam that would affect environmentally critical areas and at least 1,500 households. Since last year, Chinese coast guards have harvested giant clams and destroyed hundreds of acres of coral reefs within our own territory, and frustratingly, our government has refused to legally address this. In 2017, at least 41 environmental activists and defenders were killed, including those who protected ancestral lands. The Phillippines country has also remained in the world’s top rankings of countries at risk to climate impacts, and major global polluters of plastic waste.

Campaigning and working for sustainability is a difficult and dangerous job. While the above-mentioned list of challenges already seems burdensome, especially for a developing country, we continue to face environmentally-damaging threats from “done deal” projects between our government and the Chinese government. As an environmental planner, I am very concerned about sustainability of our resources. Let me bring to the table two pressing matters that need more effort on environmental assessments, improved legislation, and inclusive planning.

Campaigning and working for sustainability is a difficult and dangerous job. While the above-mentioned list of challenges already seems burdensome, especially for a developing country, we continue to face environmentally-damaging threats from “done deal” projects between our government and the Chinese government. As an environmental planner, I am very concerned about sustainability of our resources. Let me bring to the table two pressing matters that need more effort on environmental assessments, improved legislation, and inclusive planning.

Reclamation Projects at the Manila Bay

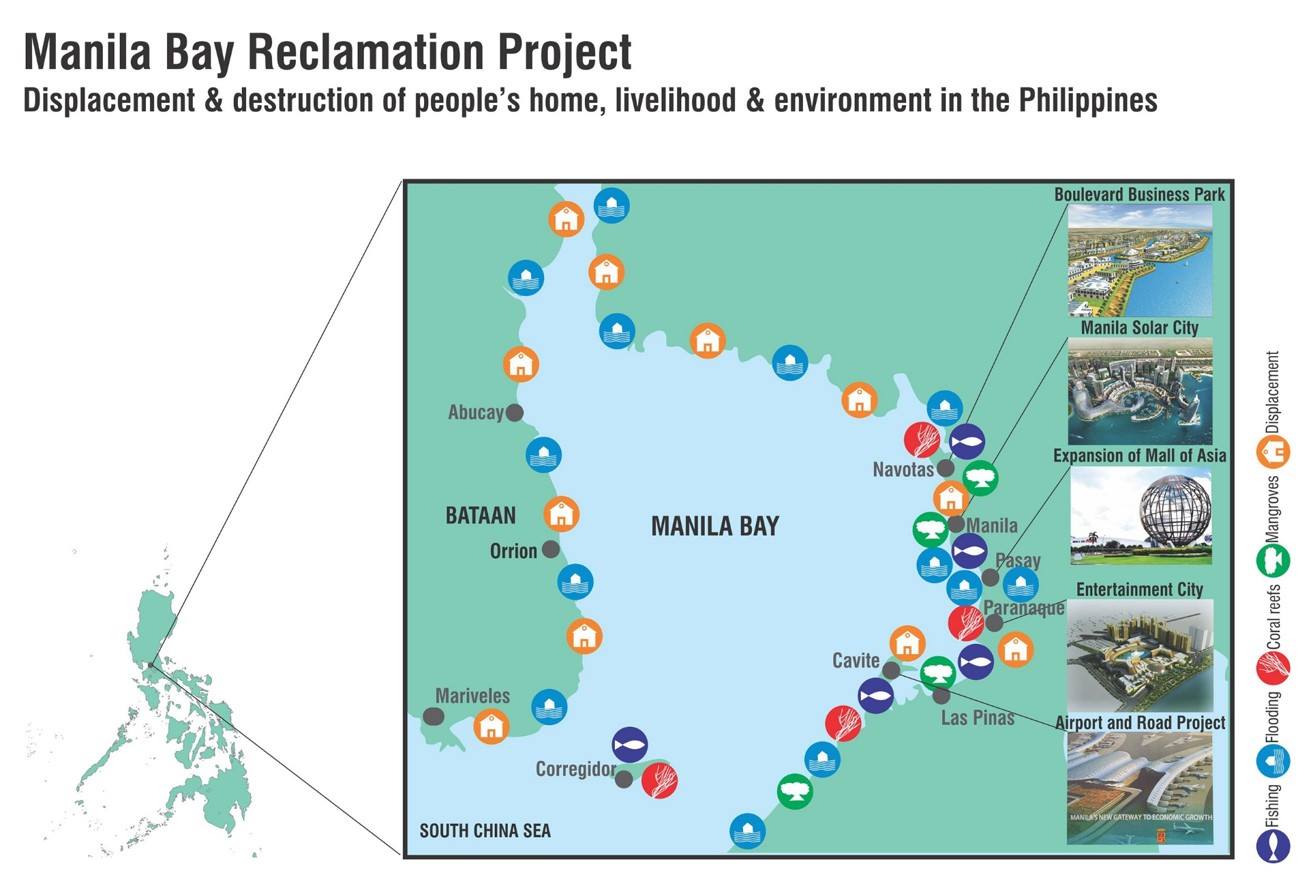

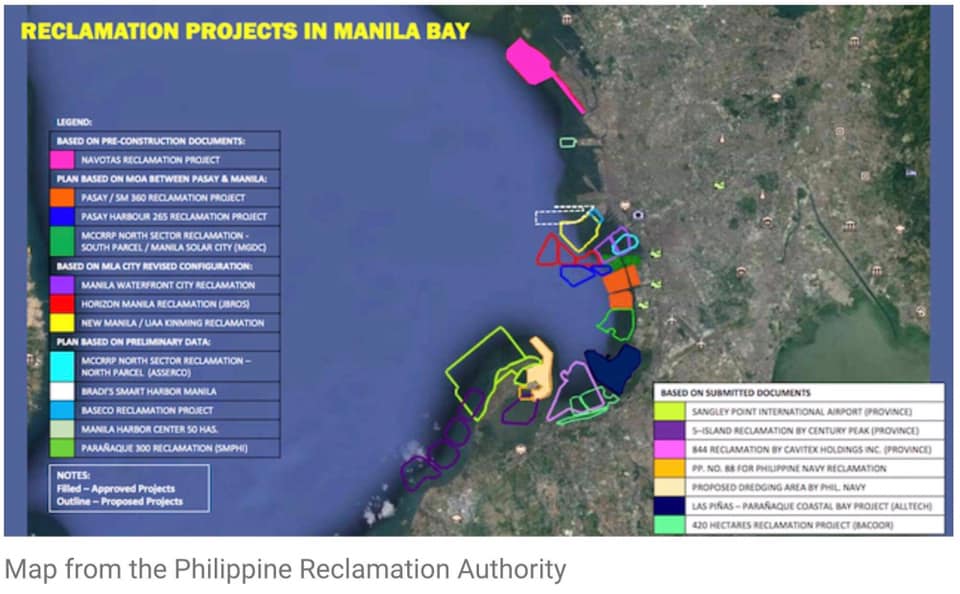

The Manila Bay is an iconic landmark in the capital city, but it has also faced problems, time and again, such as rampant poverty, reclamation for giant commercial estates, and informality that crowds around said estates. As of this writing, there are at least 22 lined up that may affect 20,000 hectares—at least 10% of the bay area. The Philippine Reclamation Authority acknowledges that there will be environmental impacts, and has released statements that reclamation areas will have mitigating systems, but this has gone without presenting environmental impact assessments to the general public. To date, only five impact assessments are available at the Department of Natural Resources Environmental Management Bureau.

The Centre for Environmental Concerns PH, a non-governmental organization, has constantly provided information on the reclamation plans. Maps show impacts on ecosystems, which include affected mudflats and mangroves, habitats of water birds and fish, and coral reefs. The socio-economic sector will also be heavily affected, and this includes issues of livelihood loss for fishermen and displacement.

Denuded mountains in Zambales

Reclamation and territorial disputes in the West Philippine Sea are hugely controversial matters in the country. Concerns predominantly revolve around the demand and supply of soils for the planned islands.

In 2016, claims were made accusing the Chinese government of extracting Philippine soils from the Zambales mountain range to build artificial islands. Though it was confirmed by a mining corporation that the soils were, indeed, transported to China, the extraction activities from the many mining sites continued, resulting in mountains denuded of trees, and damaged ecosystems. Mining activists have vocally raised concerns on reduced suitable farmlands, health issues (such as asthma and pulmonary diseases), and flood risk. In the same year, Zambales residents filed a petition to the Supreme Court with regard to the Writ of Kalikasan (Environment), but were denied a temporary environmental protection order, and eventually were dismissed, and called moot and academic. In 2018, an appeal for the same case was denied. Earlier this year, in February 2019, the mayor of the municipality in question, who blocked mining operations, was convicted of graft and usurpation of legislative powers.

Continuing the fight for sustainability

These two cases—reclamation and mining—are examples of how developing areas struggle with two pressing global issues: environmental sustainability, and at the end of the day, social justice (which does not really stray far from environmental issues).

Planners and urban managers should be at the forefront in recognizing the urgent issues that concern our landscapes and societies. More importantly, standing our ground on planning principles should enable us, and the local governments we work with, to take action. These cases bank on compliance to permits, and legal protection, making destruction of the environment allowable. Projects proceed despite protests and the lack of consultation—or guise of said process, for that matter.

While dangerous politics take the steering wheel, continuing the fight for sustainability would mean looking into understanding “development” beyond the context of economic gain, local planning that is not dependent on compliance, and revisiting legislation that truly protects our natural resources against exploitation.

Ragene Andrea L. Palma

Manila

Good article. However I would like to point out that much of the waste output by the Philippines is actually imported from many industrialized nations. In essence, poorer countries like the Philippines are carrying the burden of having to dispose the wast of the global North economies.