In some ways, this is not surprising. Local governments usually have direct control and responsibility for retaining and planting trees in public spaces, such as parks and streets. However, this control is restricted on private land, such as residential yards, gardens, or commercial and industrial areas.

The default for many local governments is to give out trees for private gardeners to plant or to educate the public about the importance of trees. But others have additional mechanisms at their disposal, ranging from legal protections, to planning strategies, financial penalties, financial rebates, and free services—in other words, both stick and a carrot approaches.

Yet, most of this information on approaches to tree retention and planting on private land lies buried in reports and local legislation. No studies, to our knowledge, have documented and synthesised these initiatives. Below we elaborate on some of the key issues on this topic and use this as a primer for our future conversation at the Nature of Cities Summit, June 4 – 7, 2019.

What’s happening with trees in private lands?

In many world cities, about half of the trees and half of the canopy cover is concentrated in private lands, areas of the cities where the city has limited jurisdiction. Researchers have documented the challenges in US and Australian cities.

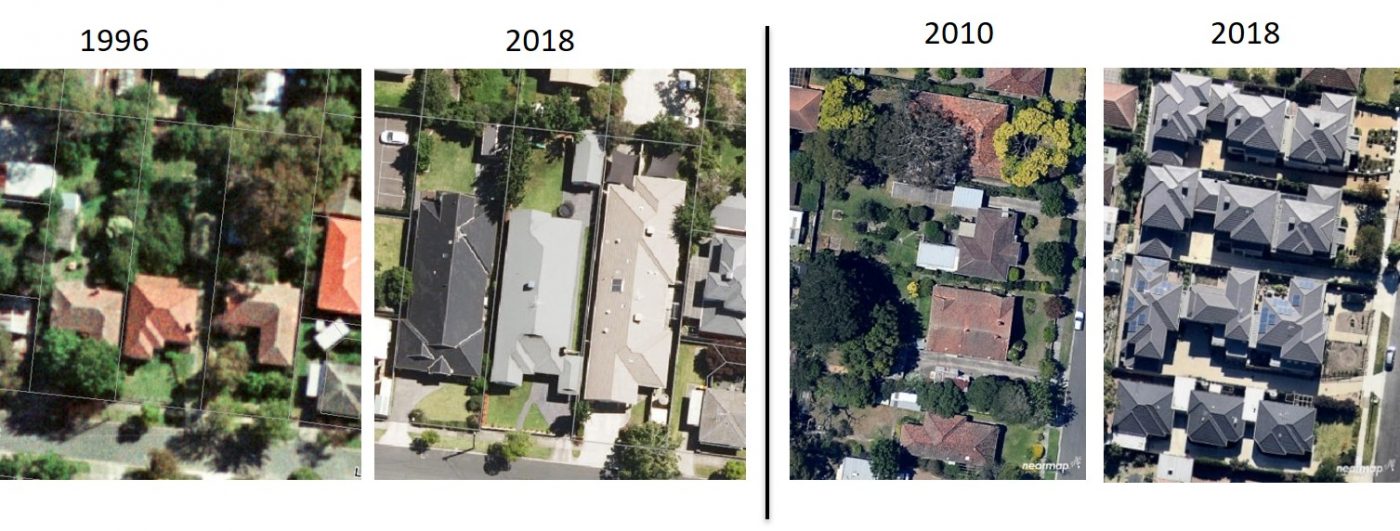

The retention and increase of trees and canopy cover in private areas constitutes an important problem for local governments. First, it makes it challenging for them to respond to and meet current sustainability and liveability requirements based on greening, since many tree decisions in private spaces are made by private homeowners or landowners, with little influence from local governments. Second, both the private ownership of trees and their unequal distribution in private spaces makes the services trees provide inaccessible to the public, contributing to justice and equity issues (see for example 1, 2, and 3). Third, because of increasing urban density, aimed at making city more liveable, many cities are losing lots of trees in private lands due to processes such as subdivision, expansion, and consolidation (Figure 1).

If we accept the notion that the services that urban trees provide are to be enjoyed collectively, then local governments have an important role to play in encouraging or regulation what happens to trees in private lands.

Stick and carrot approaches

Around the world, local governments are experimenting with a range of mechanisms to influence what happens to trees in private lands. The mechanisms can be categorized in two simple ways: penalties and regulations, or “sticks”, and incentives and promotions, or “carrots”.

Regulations, or the sticks, are specific rules and penalties that prevent the removal of existing trees or require the provision of new trees in private lands. While these regulations are usually focused on preventing the removal of public trees, many cities are now looking into implementing similar regulations for private lands (i.e., private tree protection bylaws, or ordinances, depending on context). However, the success of such instruments are largely untested.

Incentives, or the carrots, are specific activities that encourage the retention of existing trees or the planting of new trees in private lands. These include, among many others, providing rate rebates for planting or retaining trees, providing support for tree-care in private spaces, supporting citizen-led activities focused on planting or protecting private trees, awarding prizes for volunteer activities, and educating the public about the benefits of private trees. However, many cities cannot attach specific tree-related goals or targets to these activities.

The above approaches challenge all levels of government to think more creatively around jurisdictional paradigms. At the most fundamental level, they require governments to think about their urban forest as a continuous resource that needs to be managed collectively to maximise its benefits, regardless of ownership. They also require the establishment of strong community frameworks for urban forest governance that can better enable private stewardship.

However, the effectiveness of the stick or carrot approaches can be context specific, so collecting case studies from a range of cities with different characteristics (e.g., size, climate, government styles) requires building a more comprehensive understand of the pros and cons of each activity. Few studies, if any, have been able to document, synthesise, and generalize on the initiatives that cities pursue to influence what happens to trees in private lands, mostly because knowledge about these initiatives is restricted to the jurisdictional and governmental context of each city, region, or nation. This diminishes the ability of cities to learn from each other and facilitate innovation to address the challenge of retaining and planting trees in private lands.

Moving Forward

To fill this gap, we are leading a session at the Nature of Cities Summit in June 2019, where municipal officers, advocacy groups, practitioners, and researchers will meet to share experiences and collaboratively develop a suite of mechanisms to retain and increase urban trees and canopy cover in private lands. In our session entitled A stick or a carrot? – How can cities retain existing trees and plant more trees on private lands?, we aim to guide people in conversation about this topic, and share our own failures and successes. We look forward to hosting people from different cities/countries and disciplines (e.g., local government, industry, non-government, advocacy, researchers, etc.). So please, come join us at the Nature of Cities Summit in June!

Camilo Ordóñez, Judy Bush, Joe Hurley, Marco Amati and Stephen J Livesley

Melbourne

Acknowledgements: This project has been funded by Hort Innovation Australia, using the Nursery Industry research and development levy and contributions from the Australian Government. Hort Innovation is the grower-owned, not-for-profit research and development corporation for Australian horticulture. Special thanks to our colleagues Stephen Frank of TreeLogic, Meg Caffin of Urban Forest Consulting, the City of Moreland, and the City of Melbourne, Australia.

about the writer

Judy Bush

Judy is a Lecturer in Urban Planning at the University of Melbourne, Australia. Her research focuses on policies and governance of urban green spaces in the transition to nature-based cities.

about the writer

Joe Hurley

Joe is a researcher in the Centre for Urban Research, Deputy Director of the Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Research Hub, and lecturer in the Sustainability and Urban Planning program at RMIT University, Melbourne.

about the writer

Marco Amati

Marco is an Associate Professor in International Planning at RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia. Marco’s research involves urban trees, urban greenspaces, e-planning, urban agriculture, planning history, and Asian cities.

about the writer

Stephen Livesley

Stephen is an Associate Professor at the University of Melbourne, Australia. His research investigates soil-plant-atmosphere interactions in natural and managed ecosystems, and the role of urban vegetation in providing environmental and social benefits.

On July 27, 2019, Camilo wrote ‘We aim to produce a synthesis of the findings soon, and clarify the mechanisms that cities have at their disposal to retain, protect, or plant more trees in private lands’. Is this available? Thank you.

Hi Anthony,

Thank you for your comment.

Happy to see there’s interest in this topic, thank you so much for your contributions!

We’ve done a pretty comprehensive global academic literature review on this topic (please note that we focus specifically on what cities are doing or could do to protect/retain/plant trees in private lands, not public lands; public land is another issue), and there are few research papers about how private land tree retention is being tackled by cities.The only available information are reviews of the existing mechanisms, and which city is doing what, type-of-studies.

Also, there are no assessments of success. This is probably because measuring what constitutes success is difficult: hard to define what is success, and mechanisms and contexts are varied, so controlling for the effect of a specific policy or rule is difficult.

We will synthesize this information shortly, so please stay tuned for updates on this project. Thank you for your interest!

Camilo

Hi Graham,

Thank you for your support. Stay tuned for more updates about this project. We aim to produce a synthesis of the findings soon, and clarify the mechanisms that cities have at their disposal to retain, protect, or plant more trees in private lands. Feel free to write us via email.

Regards,

Camilo

Hi Cherlee!

Thank you for your comment about Free Tree. Partnership with community organizations is obviously one of the issues at hand here, so thank you!

Regards,

Camilo

Could you please give me the reference to a research paper which sid, unless the private land tree retention was tackled, any successful initiatives involving public lands will be doomed to fail? Tree/canopy cover will continue to decline.

The Australian Garden Council applauds these initiatives and wishes the organisers further success in the future.

Graham Ross VMM

Founder & Chair, AGC

Not for Profit national Charity.

I believe one of the best answers lies in the Free Tree Scheme run by Trees for Life in South Australia since 1982, where urban gardeners grow specific indigenous vegetation (canopy, understory and ground cover) fore land owners, whether privately owned land or municipalities. They have averaged about 1 million trees per annum. Get in touch with them, it’s a brilliant scheme. It also brings communities together; e.g. school and farmers.