about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

There is a feeling among many—and certainly among readers of TNOC—that in broad brush, at least, we know what we need to do to make cities better for people and nature. That is, there is a belief that if we strive to make cities more “green” though various types of green and blue infrastructure, then cities will become more resilient, sustainable, and livable. In addition, these benefits must be available to all, and so cities become more just and equitable in the provision of the benefits of green. Yet, cities often, even typically, lag in their efforts to be more resilient, sustainable, livable, and just through greening. This failure suggests we aren’t making cities better for both people and nature, even though we largely have the knowledge to do so. Why? If green is so good, what’s the impediment?

We asked a mix of scientists, practitioners, and former public officials. There are some common threads in their responses. First is that research and data, and perhaps even “knowledge” is, by itself, insufficient. We need to have vision and awareness. Now, of course, vision and awareness needs to have a foundation in grounded knowledge, but data and facts are not enough. The ideas of green cities need compelling visions of what our cities need to be, and we need to engage with everyone to create and promote these visions, even people who don’t agree with us. One element of such visions is that they need to better make the the case that “green” (in a broad sense) is part of the “must haves” of cities, alongside other vital city elements such as housing and transportation. In this case green isn’t just about, say, biodiversity, it’s about how green infrastructure, including biodiversity, are fundamental to cities that are resilient, sustainable, and livable.

Second is that while we mostly have enough research knowledge to act, it doesn’t necessarily apply everywhere. Specifically, research and knowledge derived from the North may, or may not be fully useful in the South. We shouldn’t assume that it is, and so need to develop a knowledge base that is more nuanced to regional differences and needs.

A third common thread is that in the generation and spread of useful knowledge for cities, we all have to become activists for change toward better cities. Scientists need to get engaged with practice. Practice needs to spread their ideas more actively, in the spirit that there are many “ways of knowing”. Governments need to listen more. People need to rise up for what they want.

Finally, we need transparency and engagement across sectors of the public realm: government, institutions, civil society, education, the media, and the people. Only with such transparency can ideas and their intellectual basis truly thrive. It is in the darkness of a lack of transparency and openly available knowledge that corruption (at worst) and poor decision making (at least) thrive.

about the writer

Paul Downton

Artist, writer, ‘ecocity pioneer’. A former architect with a PhD in environmental studies, Paul is distressed by how the powerful idea of ecological cities has been perverted, citing ’Neom’ as a prime example. Still inspired by his deceased life-partner Chérie Hoyle (1946-2024), Paul is continuing his graphic novel / epic poem / art project called ’The Quest for Wild Cities’ that he promised Chérie he’d finish along with his 80% complete ‘Fractal Handbook for Urban Evolutionaries’!

Paul Downton, Melbourne

In our complicated human world, with competing demands, shrinking resources and an increasing population, the promise of a technological, “smart” fix offers a kind of salvation. But reliance on algorithms can mean abdication of responsibility.

Many cities have a handle on the rhetoric and cities which have achieved actual progress enjoy well-deserved time in the limelight, but it is hard to argue that the world’s cities are becoming better places for people or nature. Many are getting worse.

There doesn’t seem to be a lack of knowledge (we’ve known about air pollution as a problem for over a century), but the overwhelming amount of data has been too much, perhaps, for decision-makers to deal with. One result is that the current go-to hi-tech answer to the challenge of taking this knowledge and applying it to improve cities is to be “smart”.

But smart city approaches are fraught with danger. They depend on ubiquitous data collection of varying levels of intrusiveness. These approaches are commercially generated and treat citizens as consumers. They offer tidiness and efficiency but rarely ask for agency on behalf of citizens, just consumption and production by customers. Some smart city apps are scary, promising to intercept unwanted activity before it happens. Thought crimes, anyone?

In our complicated human world, with competing demands, shrinking resources and an increasing population, the promise of a technological fix offers a kind of salvation. But reliance on algorithms can mean abdication of responsibility. We all know instances of people excluded or unfairly treated because the logic of a computer system failed to align with the real world of being human. Then there’s the curious, evolving insistence that we all must possess a smart phone…

Arguably, if we’re already dragging our feet on making better cities because it’s so difficult, abandoning the use of any promising technology is irresponsible. Realistically, what is the alternative?

Arguably, if we’re already dragging our feet on making better cities because it’s so difficult, abandoning the use of any promising technology is irresponsible. Realistically, what is the alternative?

Politics. Not the politics of marching to left/right whose-side-are-you-on power play, but community level politics focussed on involving people in their immediate neighbourhood, local politics that builds from the daily concerns of individuals determined to make their place better for people and nature.

The research knowledge generated by experts needs to be out in the broader community so that it can be digested and understood as part of daily life. Ideas and actions at the community level need to inform, and be informed by, that expertise. It can happen.

It’s a big ask when so much of city government is determined by the interests of land ownership and capital, but there may be no supportable alternative. If the wider population isn’t engaged and able to contribute in an informed and substantive way to decision-making, then city management ends up being reactive and, at worst, in opposition to its own citizens.

The research and knowledge base is good and getting better, but it isn’t disseminated for the same reason that ownership and control of urban areas is concentrated in the hands of a few. Knowledge is power and those who have it don’t generally give it away without a fight.

There is increasing excitement about the capacity of large corporations like IBM to provide complete, city-wide smart solutions that greatly reduce the role of elected officials or, in the case of Alphabet (“Give us a city and put us in charge”) to develop and own entire urban areas built around the use of AI and smart technology. That’s not an excitement I share, rather, I get a creeping sense of dread and a feeling that we’re slipping further into the kind of divided dystopian future that science fiction writers have long warned us against.

about the writer

Sumetee Gajjar

Sumetee Pahwa Gajjar, PhD, is a Cape-Town based climate change professional who has contributed to scientific knowledge on transformative adaptation, climate justice, urban EbA and nature-based solutions. I currently work at the science-policy-research interface of climate change, biodiversity and vulnerability reduction, in the Global South. My research interests continue to be focused on urban sustainability transitions, through collaborative governance, just innovations and climate technologies.

Sumetee Gajjar, Cape Town

While there is sufficient research and knowledge to produce cities which are good for people and nature, not all of it is applicable across the different urban contexts of both developed and developing countries.

Would it be fair to question whether the same solutions apply to cities and city-regions of the Global South? The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN adopts a wider, people-centred foundation for green cities. Such a definition gives rise to the five principles of food security, decent work and income, a clean environment and good governance for all citizens, especially the poor and the rural migrants, for developing and implementing UPH (urban and peri-urban horticulture) in multiple cities of Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. Traditional ways of greening, such as horticulture, may not be visible. However, through innovative methods of action-based research, they can be potentially accessed and enhanced using technology.

The above project is one example of solutions which better cities in the Global South could harness. Other examples include cleaning and revitalisation of urban rivers, as well as surrounding land, to achieve a clean environment, provide employment, and connect people with nature. A case in point is the UNA: Rivers Project, whereby ICLEI Africa partially funded the rehabilitation and restoration of a site in Addis Ababa (Ras Mekonnen) with UN-Habitat and City of Addis Ababa. The site was historically used as an informal waste dump site, with much of the waste ending up in the river and affecting people drinking the water further downstream. The Minecraft Tool was used to plan for effective rehabilitation of the ecological functionality of the site, whilst at the same time providing access to nature in Addis Ababa and bringing nature, and nature’s benefits, back into the city.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gl5hPfAUw1Y&feature=youtu.be

It will probably be more accurate to describe the above as practice projects, rather than policy or research, although the knowledge domains of both research and policy can learn from studying such projects. For example, the wider and longer term impacts of the FAO projects, already in implementation since 2010 would serve to inform future project designs, as well as identify which policies support their success, and which drivers undermine their effectiveness. Similarly, a longer term view of rivers restoration projects would require revisiting the sites at regular intervals, and monitoring their physical condition, the ongoing governance mechanisms, and broader aspects of well-being, including health and employment status of neighbouring communities. The range of nature-based solutions being applied in developing country contexts, whether autonomously, or through grant-funded work, can be studied and strengthened, to identify the methods (governance, technological, civic, and cultural) through which their continuity is ensured. Researching these solutions could generate knowledge that feeds into context-specific policies in the Global South.

A potential mode of knowledge generation is self-reporting by cities on their paths towards greening or sustainability, which can become the basis for further investigation, using statistical or empirical methods. This would involve as a first step, making cities aware of various approaches for integrating nature into urban and regional development and planning. One such new initiative is the CitiesWithNature platform, with a dedicated knowledge and research hub, that will showcase existing research and generate new ideas for further research on urban nature, nature-based solutions and biodiversity. It will draw on the work of a range of global grant-funded research and implementation programmes, organising and translating knowledge in a relatable manner for local governments and practitioners.

Therefore, in response to the question asked of the round table, while there is sufficient research and knowledge to produce cities which are good for people and nature, not all of it is applicable across the different urban contexts of both developed and developing countries; new research is always relevant as it helps donors, practitioners, and administrators reflect on successes and failures of previous programmes, research projects and implementation methods; and cities and city governments can benefit from mapping and measuring their trajectories and learning from the experiences of others, while trying to integrate nature into their plans and agendas.

about the writer

Russell Galt

Russell Galt works for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) where he serves as Head of the Urban Alliance – a broad coalition of IUCN Members concertedly striving to bring cities into balance with nature.

Russell Galt, Edinburgh

Conservation and development must be brought firmly into alignment. Mother Earth’s most effective foot soldiers may be those gunning for change outside of the environmental sector.

I believe that conservation and development must be brought firmly into alignment. In seeking to do so, the doctrine of New Urbanism offers a helping hand. Its promotion of integrated transit and active travel networks can be exploited to enhance ecological connectivity—for example, Edinburgh’s extensive cycle network provides a web of ecological corridors that criss-cross the city. Its promotion of locally adapted vernacular buildings can be exploited to promote the ecological tenet of naturalness—for example, many of Singapore’s iconic biophilic buildings harbour rich native biodiversity. Finally, its promotion of mixed use, diverse neighbourhoods catering to a range of income groups, ages and sectors, can be exploited to promote the ecological tenet of structural diversity—for example, London’s multifunctional greenspaces, comprising forests, shrubs, wildflower meadows, grassy lawns and wetlands, render an assortment of ecosystem services, whilst offering a diversity of niche spaces for different species to fill. (Further reading.)

Aligning conservation with development will necessitate: articulating a bold and compelling vision of a healthier and greener urban future; putting nature on the balance sheet; redefining progress; and doggedly defending our human right to a safe, clean and wildlife-rich environment. Business, government, academia and civil society all have critical roles to play. Indeed, Mother Earth’s most effective foot soldiers may be those gunning for change outside of the environmental sector.

about the writer

Naomi Tsur

Naomi Tsur is Founder and Chair of the Israel Urban Forum, Chair of the Jerusalem Green Fund, Founder and Head of Green Pilgrim Jerusalem, and served a term as Deputy Mayor of Jerusalem, responsible for planning and the environment.

Naomi Tsur, Jerusalem

One of the main problems is that the valuable, evidence-based research carried out by academic institutions around the world is rarely being translated into policy decisions for cities. I believe that a true partnership between academia and the not-for-profit sector, the latter acting not only as sponsors of research, but also as the defenders of its conclusions, is one way to impact public policy.

After spending many years opposing or modifying unsustainable development at the local, regional and national levels, I found myself in the unenviable position of Deputy Mayor of my city, Jerusalem, with the portfolios of strategic planning, historic conservation and environment. I naively assumed that in this senior political position I would be able to change the urban agenda into one based on the triple-bottom-line principle of sustainable social, environmental, and economic development. However, I soon realized that while my views were respected (although my activist past was always ridiculed), I was severely outnumbered in the city council, and unable to follow through on a considerable part of my green agenda for Jerusalem. Indeed, initiatives that I supported, such as the Jerusalem Railway Park and the Gazelle Valley Park, have been completed in spite of municipal policy and not because of it. Their completion was made possible thanks to external funding, and not through funding from the municipal budget. It is interesting to note that the current administration views both these projects as flagship municipal initiatives.

I find myself unwilling to wallow in the acute pessimism of climate change hard-liners, who warn us that immediate action is needed to prevent the continuing rise of temperatures, rise of sea levels and massive loss of biodiversity. I am also convinced that it is not helpful to find excuses in the conspiracy theory whereby national and global corporations have taken control of the economy, and unfortunately their main goal is not global sustainability, but the single-bottom-line economic profit of their companies.

On the bright side, young people today are much more aware of the centrality of these issues, and of the importance of quality of life as a prerequisite for urban living, in a world that will be ninety percent urbanized by the end of the 21st century. I noted an excellent slogan on one of the climate march banners, which read: “In a world in which leaders are not taking action, children will have to become leaders”.

The real question is: What can “we” do to tip the scales and set the course for more sustainable cities? Then there is a need to ask: “Who are “we”?” “We” are all reading the Nature of Cities, are academics, activists and NGO’s working around the world, and some of us even attended the TNOC Summit in Paris in June 2019. However, the big corporations and heavyweight decision-makers are not yet part of the discussion. So instead of bemoaning this, I would rather think what we can do without them…..

One of the main problems is that the valuable, evidence-based research carried out by academic institutions around the world is rarely being translated into policy decisions for cities. I believe that a true partnership between academia and the not-for-profit sector, the latter acting not only as sponsors of research, but also as the defenders of its conclusions, is one way to impact public policy. Traditionally, of course, academic institutions are funded by national government or by business corporations. The non-profit sector should not hesitate to enter the arena to invest in urban development research, and to be prepared to campaign in order to have their findings acted on.

From my role as chair of the Israel Urban forum, which was established in 2016, as a platform for inter-disciplinary and inter-sectoral collaboration, I see the first signs of positive impact from this kind of open platform. I wonder whether this kind of thinking could be encouraged at a global level. This year, at the third Akko Convention on Urbanism, to be held in the City of Akko in September 2019, we will be hosting a few delegations from additional national urban forums, and will work with them to bring a coherent contribution to the next World Urban Forum, in February 2020. Can we expand this discussion through TNOC?

about the writer

Adrian Benepe

Adrian Benepe has worked for more than 30 years protecting and enhancing parks, gardens and historic resources, most recently as the Commissioner of Parks & Recreation in New York City, and now on a national level as Senior Vice President for City Park Development for the Trust for Public Land.

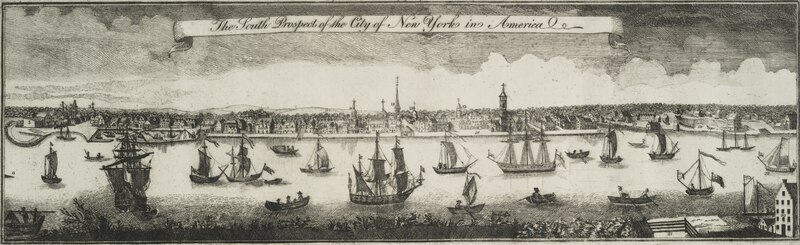

Adrian Benepe, New York

Money and politics. Many public officials and local governments, view parks and open space as simple amenities, a luxury to address after all the “vital” services have been addressed. But more civic leaders are coming to see parks and open space as crucial components of urban infrastructure, a desirable quality of life, and a civil and equitable society.

Virtually everything we do is in collaboration with others, from many levels of government and the public sector in the US, to different kinds of funding organizations which provide philanthropic gifts and grants from individuals, foundations, and corporations, to other non-profits, corporate entities, and people.

While about half of our work is dedicated to conserving land for public use in rural areas—often turned over to national and state parks, the other half of our work is in cities. In urban areas across the US, we help cities acquire land, improve existing parks, and create new parks, public spaces, and trails. In some cases, we design and build the new parks and execute the construction or renovation of parks.

There are numerous obstacles to our work, as beneficent as it may appear to most. The classic obstacles are money and politics: Simply put, many public officials and local governments, feeling overburdened by demands or public safety, mass transit, transportation, health, affordable housing, education, sanitation, and other municipal and societal needs, often view parks and open space as simple amenities, a luxury to address when revenues are flush and all the “vital” services have been addressed.

Increasingly, however, civic leaders have come to see parks and open space as crucial components of urban infrastructure, a desirable quality of life, and a civil and equitable society. They also understand that parks, open space, and trails are critical to physical and mental health, to environmental sustainability, and to climate change mitigation and adaptation. Finally, progressive city leaders understand that government can no longer do everything by itself—that collaboration with all levels of the public, private, and non-profit sectors, and particularly with citizens, is not only important to creating livable cities, but is now indispensable.

Breaking down barriers between governmental silos and between government and the many potential collaborators is the key to successful cities that are better for people and nature. From my own experience both in my daily job and in my volunteer activities, and in my prior work as Commissioner of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, here are a few examples of how cross-sector collaborations are crucial to better cities:

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): In four decades in government and the non-profit sector, I have seen the tremendous, liberating benefits of PPPs. From the birth of the Central Park Conservancy in 1981, to the present day where more than 200 such organizations are now helping to improve and manage parks. According to TPL’s research as part of ParkScore and City Park Facts, these organizations, many known as “conservancies,” currently raise in excess of $750 million a year in private charitable funds to assist in the management, maintenance, and renovation of public parks, and they are part of the recent increase in expenditures on parks that have helped to improve parks in cities across the country. Absolutely key to the success of these collaborations has been government being willing to cede some aspects of power and management to their non-profit partners, incentivizing them to devote volunteer labor and charitable gifts to services that were once the sole province of government authorities—with decidedly mixed results.

Another example of collaboration is how TPL works in cities to renovate existing parks and build new ones. In more than 20 American cities, TPL has helped to create or renovate thousands of parks and trails, including transforming more than 200 New York City asphalt schoolyards into green community playgrounds. In each case these projects involve cross-sector collaboration between TPL and NYC government agencies, using a combination of public funds and private gifts, and engaging school children and neighborhood residents in a “community engagement”-focused design process. The result are improved spaces that help improve the local environment for underserved areas, while creating beautiful new community spaces that are less likely to suffer vandalism and neglect because of the “ownership” by the residents who were full partners in the playgrounds’ conception.

- Public-Public Partnerships: Some of the best examples of new and innovative parks and public spaces have resulted from partnerships between various levels of government—in the US, that largely means city, county, state and federal. Two of NYC’s largest and most impactful new parks—Hudson River Park and Brooklyn Bridge Park—were the result of creative collaborations between the City of New York and New York State. In both cases, quasi-governmental development and management agencies were formed, with boards composed of members named by government leaders and including local elected officials. But they were liberated from some of the Gordian knots of bureaucracy, and were able to function more like the private sector in terms of issuing contracts and entering into partnership. Also, in each case the authorities set aside portions of the future parks as income-producing properties, to fund the enormous operating costs of these new waterfront parks. For example, in the case of Brooklyn Bridge Park, 10 percent of the former shipping piers and wharves area was set aside for the development of hotels and residential buildings at the edge of the future park. Those site now generate up to $16 million a year in ground rent, which is used to fund the operating expenses and capital upkeep of the park.

The above are just two of thousands of examples of the beneficial—indeed vital—need for collaboration in the interest of making cites that are better for people and nature.

about the writer

Huda Shaka

Huda’s experience and training combine urban planning, sustainable development and public health. She is a chartered town planner (MRTPI) and a chartered environmentalist (CEnv) with over 15 years’ experience focused on visionary master plans and city plans across the Arabian Gulf. She is passionate about influencing Arab cities towards sustainable development.

Huda Shaka, Dubai

To create better cities we—planners, designers, and policy-makers—need to find a way to work much closer with the residents and users of the city. Otherwise, even the best-intentioned plans may have poor outcomes. Data alone is insufficient. We require transparency and freedom of expression in all arenas.

There may be an extensive body of knowledge available on the theory and practice of city planning; however, there remains a knowledge gap in the Arab world. There is a scarcity of local data and locally-relevant research. Planning for human and natural wellbeing would benefit greatly from recent and rigorous studies on environmental quality, social habits and behaviours, and cultural preferences and norms. This is particularly true for the newer and more culturally and socially diverse cities of the Arabian Gulf.

Similarly, a more accurate database of natural resources and their value to communities and the planet is required from an environmental perspective. Information as simple as habitat mapping or historical sea levels is difficult and sometimes impossible to access. In addition, the information may be available at a national level, and not at a city or regional level. This adds a layer of difficulty and uncertainty when assessing and interpreting the data.

Creating this knowledge requires capable research-focused educational institutions, as well as the funding and policy support to undertake the research. Some cities are starting to respond to this need through the support of world-class research institutions and the facilitation of data sharing through policy.

The second aspect is raising public awareness of the value and importance of our natural assets and the impacts of unsustainable planning and design. This is an important part of creating the “demand” and grassroots pressure for a more people and nature friendly built environment.

Most people I talk to recognize the symptoms of bad planning—obesity, stress, anxiety, loneliness, high resource consumption. What they fail to see are the causes, many of which relate to the built environment: air quality and noise pollution from cars and construction, lack of access to spaces for physical activity and chance meetings, disconnection from the natural environment…etc. Once people realise these connections, they also begin to realise the changes that need to happen to the way we plan, design, develop and operate cities and neighbourhoods. They become more aware of the decisions they can make to promote their wellbeing and that of others around them.

Once again, this awareness will come from education, and from disseminating relevant data and information to the public. It will also come from an informed discourse on environmentally and socially responsible city planning, design, and operation in public forums. This requires a degree of transparency and freedom of expression in the media, in public forums, at schools, and in the workplace. Data alone is not sufficient.

Public awareness will have a limited impact unless meaningful public engagement becomes part of city planning. This is currently almost non-existent in Arab cities, particularly in Gulf cities. I would argue that even where it does exist in other parts of the world, it is not effective because engagement is often limited to information or consultation. To create better cities we—the planners, designers, and policy-makers—need to find a way to work much closer with the residents and users of the city, current and future. Failing to do this will mean that even the best-intentioned plans may have unintended consequences, and the remaining majority will go through even if they are not in the best interest of people or planet.

about the writer

Ana Faggi

Ana Faggi graduated in agricultural engineering, and has a Ph.D. in Forest Science, she is currently Dean of the Engineer Faculty (Flores University, Argentina). Her main research interests are in Urban Ecology and Ecological Restoration.

Ana Faggi, Buenos Aires

There is always large inertia for change. People, including politicians, institutions and the community have difficulties to move beyond short time thinking, and multiple agendas always slow progress.

The first one is a bottom up project at a neighborhood-scale; a square in Floresta, a typical neighborhood with few square meters of green space per inhabitant. Since the 1980s, a group of residents has struggled to transform a site dedicated to the management of urban solid waste to a green area for recreation. These people have been trying to convince municipal managers for more than 30 years of the importance of this transformation. The process was delayed not only by the political ineffectiveness, also through conflict of interests of different sectors of the civil society who were unable to join a collective project. Finally, the square was completed, although with a smaller area than was proposed at the beginning, since a school was built on the area. Today it is a space that offers multiple recreational activities for different age groups.

The other project that responds to a top down governmental initiative took 15 months to complete and refers to the pedestrianization of the famous Corrientes Avenue. Such a project is comparable to initiatives already implemented in the Gran Vía of Madrid and Times Square in New York and sought to relocate the Avenue Corrientes as one of the great cultural and entertainment attractions of Argentina and Latin America. The avenue combines the largest concentration of theaters, a large network of bookstores and restaurants. Years ago, because of its deteriorated state, Corrientes was not an inviting place to walk, the insecurity and the economic crisis had taken away it attraction. This revitalization seeks to attract more tourism, which generates a lot of work in the City, including hotels, restaurants and entertainment.

The project began in January 2018 and consists of a comprehensive intervention that includes two lanes with night pedestrianization and two exclusive lanes for buses and taxis and the incorporation of rest areas. After 15 months of work, during which the avenue was more like a workshop than a cultural pole, Corrientes operates with two lanes for public transport and another two for private vehicles, with a dividing central mason. Vehicles will be able to circulate until 19:00h in the afternoon. From that time and until 0200h in the morning, that last section will become pedestrian. Many people opposed this work due to the inconvenience it caused—such as the decrease in theater audiences due to the difficulty of going to the area—its high cost at a time when the economic situation is bad in the country—as well as the rejection of the owners of the parking lots and some doubts of urban planners .

These two examples show that in projects there is always large inertia for change. People, including politicians, institutions and the community have difficulties to move beyond short time thinking. To this we must add that each project is triggered by multiple forces that can put the stick in the wheel of initiatives that are known to be successful in other parts of the world or that respond to participatory processes who seek the common good.

However, it makes clear that the engine to generate changes can be faster if there is the political power to make them.

about the writer

Vivek Shandas

Professor Vivek Shandas specializes in integrating the science of sustainability to citizen engagement and decision making efforts. He evaluates the many critical functions provided by the biophysical ecosystems upon which we depend, including purifying water, producing food, cleaning toxins, offering recreation, and imbuing society with cultural values.

Vivek Shandas, Portland

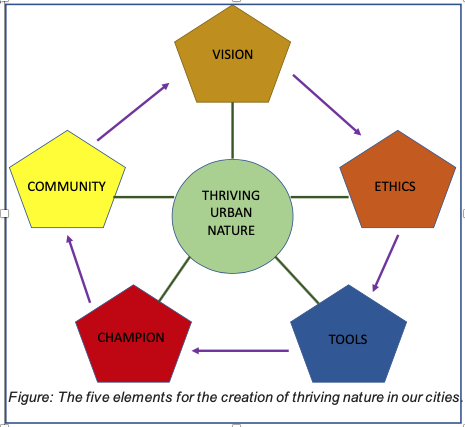

Vision, Ethics, Tools, Champions, and Community are the drivers of what cities are. Each are essential though free-standing and exclusive; they work in concert to align the multiplicity of human-made systems to create the landscape that advance urban nature.

Anybody who rides a bike knows that several factors have to come together to support stable and continuous pedaling. Physical strength, capacity, and conviction, adequate space, encouragement, and of course access to the bicycle itself. Each of these factors have to work in concert to enable an individual to balance themselves as they propel themselves through space. Not surprisingly, many of our everyday activities—cooking, sleeping, commuting, defecating—require a series of systems to align, and harness the necessary elements to enable everyday life. In places where these systems are misaligned or maladapted, we witness challenges in supporting everyday necessities.

If we know that exposure to nature everyday is important to our health and well-being, and urban ecosystem provide essential services for our survival, then why are we not seeing an abundance—indeed thriving nature—in all human settlements? What systems are not coming together to enable the provision of natures services to the places where the majority of humans now live? Indeed, why do some places have more urban nature than others?

Creating cities that are thriving ecosystems continues to face challenges due largely to rapid urbanization, landscape homogenization, and the systematic removal of legacy ecosystems. While extensive research points to urbanization, landscape homogenization, and systematic fragmenting and conversation of remnant ecosystems as reasons for the lack of nature in cities, these factors are often the byproduct of more fundamental processes occurring in our cities. As a way to unpack the complexity of narratives for supporting urban nature, I’ve endeavored to organize five elements that are both necessary and complementary. The five elements represent the basis upon which decisions about our landscapes are made. I argue that claims about “more funding” and “tempering development” are symptoms of the visions and ethics that underlie the physical manifestation of our cities. Below, I describe each of the elements, and describe their potential role in aligning systems that can support and enrich thriving urban nature.

An essential element for creating cities that are better for people and nature requires a Vision. The vision is as much a symbol as it is direction for a community. Second, Ethics in this context represent the norms, behaviors, and activities of a community as they recognize the importance that urban nature plays in our lives. In other words, what is considered “normal” in the context of a community. In many cases, educational systems—from preschool through college—are instrumental in establishing ethical norms. If the vision and ethics are in place, communities will likely support the building of Tools that help to characterize, understand, and maintain urban nature. These tools can come in a variety of forms, including programs by local organizations, online platforms, policies and plans, and protocols. The classic Dr.Suess story The Lorax is the quintessential Champion for nature. These are individual, organizations, and other entities that use their agency to advance the integration of nature into our cities. Finally, a Community provides a means for sharing the collective benefits, rituals, and recognition of urban natures.

An essential element for creating cities that are better for people and nature requires a Vision. The vision is as much a symbol as it is direction for a community. Second, Ethics in this context represent the norms, behaviors, and activities of a community as they recognize the importance that urban nature plays in our lives. In other words, what is considered “normal” in the context of a community. In many cases, educational systems—from preschool through college—are instrumental in establishing ethical norms. If the vision and ethics are in place, communities will likely support the building of Tools that help to characterize, understand, and maintain urban nature. These tools can come in a variety of forms, including programs by local organizations, online platforms, policies and plans, and protocols. The classic Dr.Suess story The Lorax is the quintessential Champion for nature. These are individual, organizations, and other entities that use their agency to advance the integration of nature into our cities. Finally, a Community provides a means for sharing the collective benefits, rituals, and recognition of urban natures.

The creation of laws in Ecuador, New Zealand, and several other nations that recognize that nature has rights is arguably the culmination of all five of these elements. Each are essential though free-standing and exclusive. Similar to riding a bike, they work in concert to align the multiplicity of human-made systems to create the landscape that advance urban nature. We all have a role to play—indeed can be champions—to enable those systems that can help to advance a vision, ethics, tools, and community for supporting nature in our cities.

about the writer

Philip Silva

Philip’s work focuses on informal adult learning and participatory action research in social-ecological systems. He is dedicated to exploring nature in all of its urban expressions.

Phil Silva, New York

Villainy, lag, inaccessible knowledge, lack of respect for different ways of knowing. These all play a role. We may have all the “research knowledge” we need in order to get to work, but we still need all the practical knowledge we can get. Practitioners, in turn, need help getting the knowledge the produce out in the open and available to their colleagues all around the world.

First, we always have to confront the presence of outright villainy in our efforts to apply scholarly research to the work of improving cities. Greed, apathy, ignorance, ineptitude, cowardice, prejudice, and laziness are all daunting barriers to getting anything done, no matter how much good research we have on hand to back up a progressive change in policy or practice.

Second, it’s reasonable to expect a lag between the production of scientific research and its translation and implementation into practice. “Science, if it can deliver truth, cannot deliver it at the speed of politics,” wrote the sociologists Harry Collins and Robert Evans. Scientific consensus takes time to form around even the most straightforward and linear of topics, never mind the multivariate, complex, and emergent issues we face in contemplating urban sustainability. So, in some cases, we may simply be witnessing a delay in the “uptake” of research caused by the very nature of science as a deliberative social process.

Third, we need to consider the different ways scholarly research remains inaccessible for most practitioners. Journal articles and academic monographs are locked up behind digital paywalls and inside research libraries that don’t offer open access to the general public. Scholarly research interests are, by their nature, too specialized and esoteric to resonate with the work of most generalist practitioners, making the mountains of literature on urban sustainability and resilience functionally irrelevant to many people tasked with making tangible change. And, as the organizational scholar Donald Schon pointed out, when faced with the choice between technical rigor and societal relevance, scientists will typically follow a line of inquiry that allows for greater control, generalizability, and stability (ensuring a higher degree of rigor) shying away from exploring messier “real world” problems.

Fourth, those of us straddling the domains of scholarship and practice know that science does not have a monopoly on the production of valid, rigorous, and reliable knowledge. And, by extension, scientists are not the only members of our society capable of producing the knowledge necessary for solving the problems of sustainable and resilient cities. “Citizen science” and other forms of “public participation in scientific research” have created opportunities for practitioners to “co-create” scholarly knowledge with researchers, but the products of their research collaborations are often subject to the same issues of accessibility I’ve outlined above.

What about all the knowledge produced every day in action—the humdrum knowledge forged, tested, and preserved in practice over time? The inherent pragmatism of this sort of knowledge makes it absurd for us to ask whether we’ve accumulated enough of it and whether we need to make any more of it before we can get to work. The very act of “getting to work” is the engine that drives the production of what Schon called knowledge-in-action, and practitioners couldn’t shut the engine off even if they wanted to—and why would they? Yet much of this knowledge wrought in practice is tacit and goes unspoken unless practitioners take extra steps to reflect on their work together and surface, to the extent possible, what they’ve come to know from doing. Becoming a “reflective practitioner” (another Schon-ism) takes serious effort, and most practitioners probably don’t even see themselves as being in the knowledge production business to begin with. After all, that’s what scientists are supposed to be busy doing.

We may have all the “research knowledge” we need in order to get to work, but we still need all the practical knowledge we can get. Practitioners, in turn, need help getting the knowledge the produce out in the open and available to their colleagues all around the world.

about the writer

Rob McDonald

Dr. Robert McDonald is Lead Scientist for the Global Cities program at The Nature Conservancy. He researches the impact and dependences of cities on the natural world, and help direct the science behind much of the Conservancy’s urban conservation work.

Rob McDonald, Washington

The way around the barriers to better cities is not more scientific knowledge and studies, as much as it pains me as a scientist to say it. What is needed is more inspiration, a passion to achieve a shared vision of what a thriving, green city could look like.

- Public concerns: Nature in cities is sometimes messy and problematic. Think about fallen limbs causing power outages, or trees and untended parks providing spaces for criminal activity. Until public concerns about these issues is addressed, the public will not whole-heartedly support our vision of a thriving, green city.

- Silos: The opportunity to return nature to cities touches virtually every part of the urban landscape—from city streets and parks to private residential and commercial property. Yet the formally designated responsibility for nature often falls on just one municipal agency, such as a city’s Department of Parks and Recreation. As a result, it can be difficult for cities to efficiently identify opportunities to restore or expand urban nature that might be presented by the on-the-ground work of different municipal agencies.

- Lack of financial resources: Trees and parks are often considered a “nice to have” item when compared to other critical municipal needs such as police and fire protection, education, roads, and other public services. This perspective, combined with the annual budget cycle of most cities (as opposed to longer-term planning considerations) leaves urban nature programs minimally funded, and often at risk of reductions.

The way around these three barriers is not more scientific knowledge and studies, as much as it pains me as a scientist to say it. What is needed is more inspiration, a passion to achieve a shared vision of what a thriving, green city could look like. The inspiration can come from the top-down, as mayors and other municipal leaders reimagine what their city can be. Or, as often, the inspiration can come from the bottom-up, from a set of activists in a neighborhood creating and advocating for their own shared vision of a thriving, green neighborhood. Inspiration can motivate public support, overcoming particular public concerns. Inspiration can bust through government silos, if there are enough people demanding that change. And inspiration can usually motivate municipal leaders to find funding for urban nature.

Humanity is in the period of fastest city building in its history. We are designing the cities of the future now, and those cities will only have nature in them if humanity passionately wants that greener future. We will choose the urban world we create, and we will get the urban world we deserve.

Leave a Reply