A hot topic within both global and metropolitan land conservation circles lately has been to articulate bold targets for land set asides. The highest profile of these recent efforts has been the Half-Earth Project, spearheaded by the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation. In 2016, Dr. Wilson, in an article in the New York Times, recommended that 50 percent of the Earth’s surface be conserved in a natural state to support and maintain biodiversity, which he felt was “the only way to save upward of 90 percent of the rest of life”. Since this declaration, the Half-Earth Project expanded in 2019 to include a Half-Earth Pledge and a Half-Earth Day on 7 October 2019.

While this has been the highest profile effort to date, the earliest article I could find researching the topic from a city perspective was on the Nature of Cities website by Lynn Wilson. In her 2014 article entitled “Nature Needs Half”, she documents the work of the WILD Foundation and its WILD Cities Project and references the Fund’s pioneering work establishing a conceptual green infrastructure framework and implementing green infrastructure at multiple scales to explain how the Capital Region District in British Columbia, Canada could consider and implement the Nature Needs Half concept, which advocates protection of 50 percent of the planet by 2030.

In April 2019, some of the same principals involved in the Nature Needs Half initiative reframed the aspiration in an article in ScienceMag by promoting a Global Deal for Nature, which targets 30 percent of the Earth to be formally protected and an additional 20 percent designated as “climate stabilization areas”, which, as defined by the article, are “habitats like mangroves, tundra, other peatlands, ancient grasslands, and boreal and tropical rainforest biomes that store vast reserves of carbon and other greenhouse gases”.

In the US in August 2019, a political advocacy group, the Center for American Progress (the Center), jumped on the bandwagon to try to convince policy makers they should adopt and implement a goal of protecting 30 percent of US lands and oceans by 2030. The Center is correct that the US “lacks a clear, common vision for how much nature it wishes to conserve, in what form, at what cost, and for whom” and therefore has vastly underutilized its capacity to conserve nature. I could not agree more on that point!

In our book The Science of Strategic Conservation: Protecting More with Less, Dr. Kent Messer and I point out that billions have been spent on land conservation but too little attention has been paid to how strategic and cost-effective these investments have been. To get to 30 percent or 50 percent protection of the globe or a specific geography, understanding priorities and the opportunity cost of investing in one form versus another is essential. And as the Center correctly points out in its Issue Paper: “A discussion of how much nature to protect—and how, where, and for whom—must honor and account for the perspectives of all people, including communities that are disproportionately affected by the degradation of natural systems; communities that do not have equal access to the outdoors; tribal nations whose sovereign rights over lands, waters, and wildlife should be finally and fully upheld; communities of color; and others.”

So how do we translate these global goals into actionable goals for nature in cities? Tim Beatley wrote about the Half-Earth project in his monthly column in Planning magazine in July 2018. He discussed the potential role of cities in implementing the concept with Paula Ehrlich, CEO of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation. Beatley correctly points out that “urban areas can and must be part of the Half-Earth vision and strategy for it to succeed”.

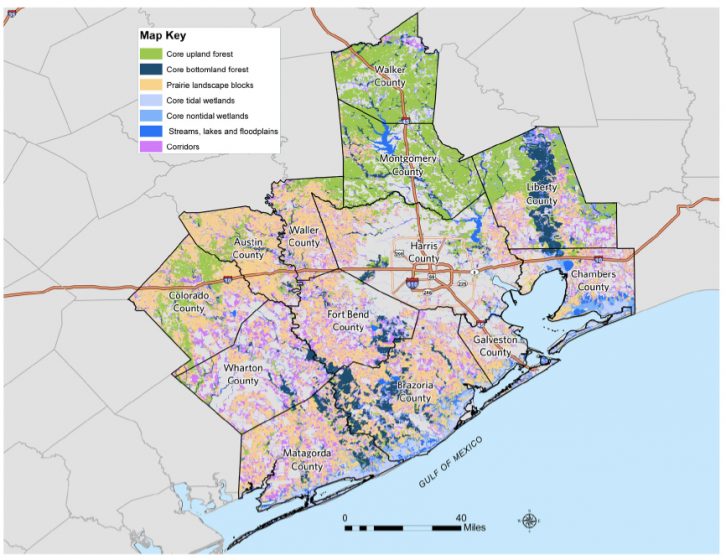

To realistically move towards any aggregate protection goal in the US, or the world, will require metropolitan areas to establish bottom-up goals based on the geographies of their region. One such effort is being spearheaded by Houston Wilderness. In a precursor project to the Regional Plan completed in 2013 focused on green infrastructure and ecosystem services, the Fund found out that in a 13-county area in Houston, 62 percent of the land provided 91 percent of the ecosystem service benefits (see the map below).

The 2019 Gulf-Houston Regional Conservation Plan covers eight counties in and around the City of Houston, the fourth largest US city by population, and has the following three goals: (1) Increase the current 9.7 percent in protected/preserved land in the eight-county region to 24 percent of land coverage by 2040; (2) Increase and support the region-wide land management efforts to install nature-based stabilization techniques, such as low-impact development, living shorelines, and bioswales, to 50 percent of land coverage by 2040; and (3) provide research and advocacy for an increase of 0.4 percent annually in air quality offsets through carbon absorption in native soils, plants, trees, and oyster reefs throughout the eight-county region. In implementing this 2019 plan, it will be important to understand a key lesson learned from the 2013 ecosystem service analysis that it is not just important to reach 50 percent but that it needs to be the right 50 percent.

Clearly, to come close to meeting percentage targets like this by a certain date are going to require significant investments at multiple scales. For instance, the US Federal Land and Water Conservation Fund will need to have appropriations much closer to its maximum annual accrual limit of US $900 million, and the magnitude of state and local bonds will need to increase (over US $3 billion in 2018).

Metropolitan areas in the US, such as Portland, Oregon, have developed Regional Conservation Strategies to help them protect strategically important areas and spend available money wisely, but they have not emphasized specific targeted percentages. The Intertwine Regional Conservation Strategy, in tandem with the Biodiversity Guide for the Greater Portland-Vancouver Region, defines the challenges that the region faces to protect local wildlife and ecosystems and offers a vision, framework, and tools for moving forward collaboratively to protect and restore natural systems.

In synthesizing all of these global and city initiatives, my concern goes back to some of the fundamental principles of green infrastructure that the Fund helped outline starting back in the early 2000s, culminating in the book: Green Infrastructure: Linking Landscapes and Communities. These percentage goals are not a substitute for a strategic analysis for identifying what is important to protect that keeps natural systems and human communities thriving. These goals are also not a substitute for building local constituencies to support achieving conservation goals, as the bi-partisan polling referenced at the beginning of the article suggests there is a disconnect between the general public and current political leadership on these topics. As I like to say: “Figure out where the green infrastructure should be and then build the gray infrastructure around that”. In city contexts, these percentage goals could have the unintended consequence of establishing protected lands that have little relative value for wildlife and people. In the case of both Portland and Houston, both are backed by rigorous analysis of the needs, and it is not that relevant that one has specific numerical goals and the other one does not. What’s most important are that there are intelligent, data-driven goals, and those goals will vary based on the metropolitan area.

Even if one has a conceptual problem with oversimplifying land conservation into percentages, Beatley articulates the value of these types of efforts. Embracing this type of vision “reflects the philosophy that all forms of life matter, that they have inherent worth, and that cities have an ethical duty to blanch biological hemorrhaging.” Beatley asks: “Is it possible a new kind of urban ethic could emerge, one that understands the imperative of cities to conserve and protect nature, local and distant? Can we enlist cities and urbanites in the global struggle to preserve species and ecosystems that are often removed from their daily sight or consideration?” Houston Wilderness and The Intertwine have made statements that they are serious about their role in global conservation. Who else will join them?

Will Allen

Chapel Hill

Add a Comment

Join our conversation