It is imperative that a transdisciplinary approach that acknowledges disciplinary assumptions and boundaries to transcend them is supported. For example between managers, planners, designers, developers, residents, policymakers and researchers.

An output of a TNOC Summit Seed Session, Paris, 4 June 2019. Click here for other outputs from the Summit.

The three frames: Wild, Stray, and Care

The three frames: Wild, Stray, and Care

“Wild, stray and care” seek to problematize boundaries, such as natural / artificial, human / non-human, and progressive / regressive. Acting as both verb and noun, “wild’ may be interpreted as “first nature” to presume authenticity, as “wild-in-nature” as represented by natural predators or indeed as uncontrollable human behaviour. “Rewilding” presents another interpretation, as in ecological restoration to reintroduce and to return animals “home”. Alternatively, “stray” could represent an outsider species living in liminal space, homeless, unwanted—as an exile, exotic, introduced or wild native species that has entered a foreign space. Often designated as “pests” or “weeds”, such intruders are often downplayed, de-valued and dismissed within urban environments. Finally, “care” offers possibilities for rethinking about human / nonhuman engagements with one possible outcome constructing a bridge of “entangled empathy” to de-centre human’s privilege over all other urban nonhumans (see Edwards et al. forthcoming).

The Nature of Cities Summit Seed Session

The seed session, “Wild, Stray, Care: Exploring multiple ways people co-exist with urban nature” got off to a roaring start at The Nature of Cities Summit in Paris. With artists, geographers, urban planners, anthropologists, policy makers, landscape architects, ecologists and NGOs in attendance representing cities across the world—South Africa, France, the United States, Australia, Belgium, India, Ireland, Russia, UK, Africa, China, Spain and Singapore—we sought to disrupt conventional frames of “nature” towards creating more harmonious multi-species cityscapes. During the seed session three questions were explored. The responses are briefly summarised below.

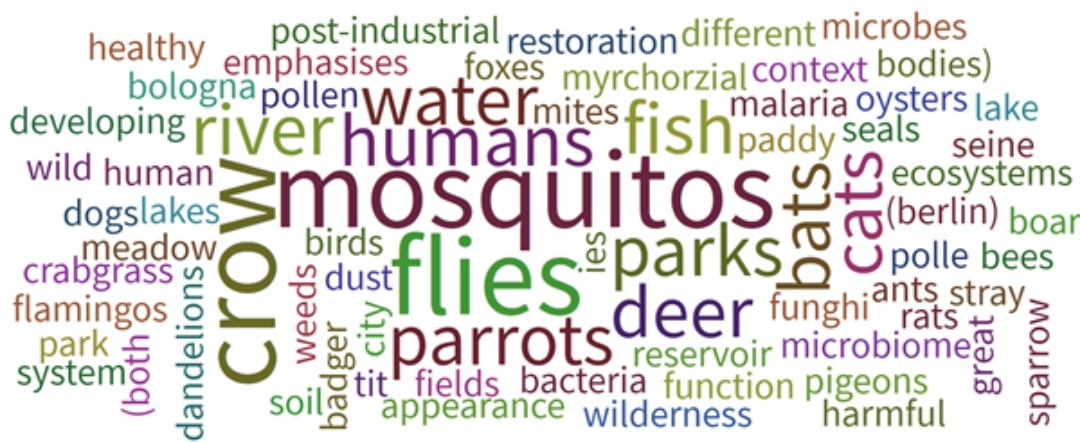

What is your favourite urban nonhuman?

The warm-up question immediately raised queries about disciplinary preconceptions of “nature”. Can nature be conceptualised as an individual species (such as nightingale, dogs, or birds), as a conglomerate ecosystem (such as “woods, real wild woods”), or as a singular species that leads one into a relational web of life (such as ants that introduce us to soil, other insects, plants and more)? Where does urban nature begin or end: on / in land (clover, dandelion), in waterways (otters, manatees or reeds) or air-blown (as solitary bees)? Are only pretty or distasteful species recognised (cats or cockroaches) and if so, what about all those species in between?

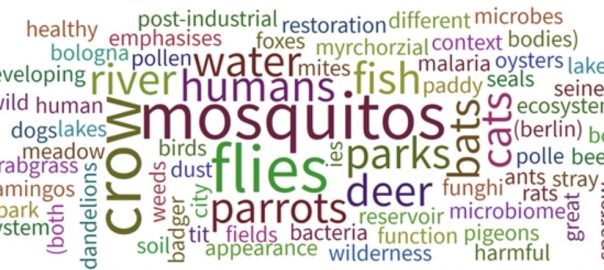

Attendees were then asked three key questions with their responses captured by a mix of butcher’s paper, sticky notes, mobile technologies, word clouds (captured by Poll Everywhere), note-takers and photographs.

What natures exist in your city?

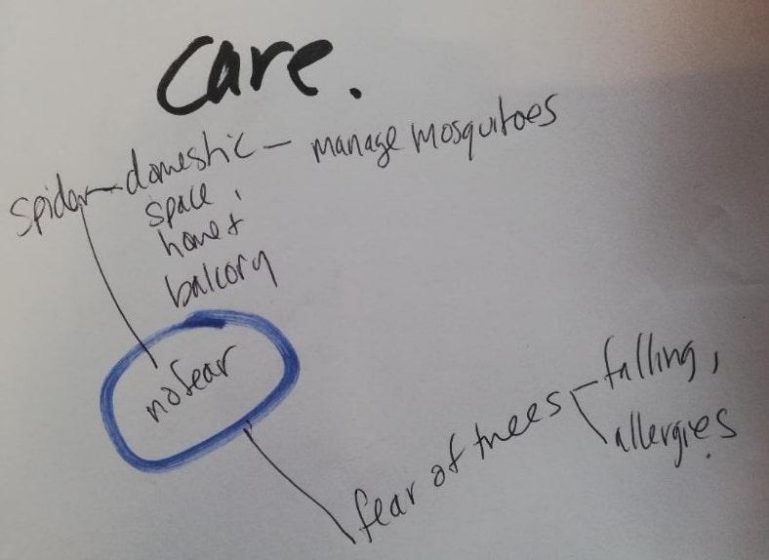

This next question delved deeper into how humans sense urban natures in a range of environments based with consideration of the three frames. Amplifying the categories mentioned above (loud, pretty or distasteful species, and singular and composite ecosystems), new recruitments included the very small (dust mites, mosquitos, flies, microbes, bacteria, mycorrhizal fungi and pollen), the meso (parks) and the macro (forest patches, island trails). Species that transgressed categorization where also acknowledged as they move from wild to stray to care and back again as they intersect with other species and situations.

For example, water hyacinth from Lake Victoria (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda) is a wild species that invades other water systems through lake chains and plane travel preventing navigation (stray). Its overproduction is a good source for furniture-making (care), while by preventing human navigation, water hyacinth creates conditions for the wild return of fish species.

Conversation topics included how care is often focused too much on appearance versus function, a question about human-framed perception on how do you know nature’s there, while parrots, deer, bats and cats were recognised as the most common shared species across all attending cities. One respondent’s responses illustrate a city’s specificity to the frames where, based in Singapore: “wild” is considered as primary tropical forests that fill one with awe, as complex systems that are heterogeneous, multi-layered forests, that are dynamic, mysterious and vibrant providing luxuriant food; while “stray” evokes: spontaneously growing plants, rambunctious transitory and temporary growth, a possible wicked problem, something that is incomplete, unintentional fauna, transforming—there are not many “strays”. Finally, care is seen to be manicured, intentional maintenance, protective, controlled, attentive, designed and manipulated space and animals, where the most distinctive nature that she senses are manicured open lawns with single-tiered vegetation and biotic homogenization. There is also an appreciation of the incredible biodiversity due to topicality.

Conversation topics included how care is often focused too much on appearance versus function, a question about human-framed perception on how do you know nature’s there, while parrots, deer, bats and cats were recognised as the most common shared species across all attending cities. One respondent’s responses illustrate a city’s specificity to the frames where, based in Singapore: “wild” is considered as primary tropical forests that fill one with awe, as complex systems that are heterogeneous, multi-layered forests, that are dynamic, mysterious and vibrant providing luxuriant food; while “stray” evokes: spontaneously growing plants, rambunctious transitory and temporary growth, a possible wicked problem, something that is incomplete, unintentional fauna, transforming—there are not many “strays”. Finally, care is seen to be manicured, intentional maintenance, protective, controlled, attentive, designed and manipulated space and animals, where the most distinctive nature that she senses are manicured open lawns with single-tiered vegetation and biotic homogenization. There is also an appreciation of the incredible biodiversity due to topicality.

How are those natures being managed?

Popular responses to the second question included a predisposition for hygienist and a human safety focus where reactive measures were taken against fear or anger to create places devoid of assertive forms of nature. Rather than softly mediated relationships with nature, heavy-handed regulation by government plays a large role. For example, in Australia killing is an intense strategy for managing stray species such as an overpopulation in kangaroos or stray dogs and cats. Alternatively, some species defy management efforts where the best management strategy is to not manage nature at all, allowing instead for “wild” nature to blossom and self-regulate in cities. Again, to illustrate the complexity within a Singaporean perspective, “wild” represented protected, highly managed “nature” as the leftover primary wild forests where these are precious; “stray” is infrequent due to land scarcity and clear ownership, while “care” is everywhere, as a one hundred percent urbanized city state, the government has done much taking care. Tidy forms of nature persist under the nation’s Garden City vision that emphasized providing visitors and investors a clean and favourable impression of the country. There is barely even a single patch of the land bare (either turf or paved).

What possibilities can you envision to more positively co-exist with urban natures?

What possibilities can you envision to more positively co-exist with urban natures?

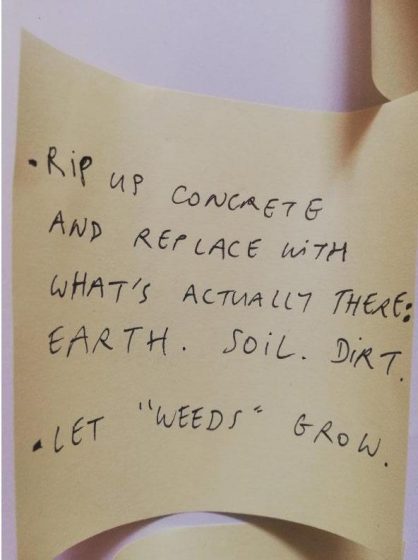

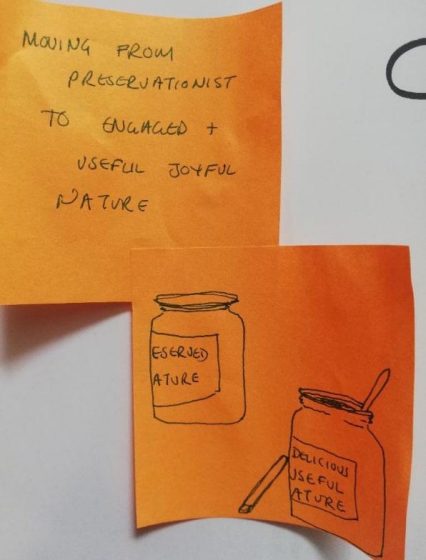

The final question encouraged both fantastical and pragmatic possibilities of future urban natures. Thinking big, conversations explored issues of spatial and temporal scales and their implications for cities in times of climate change (will cities be on or under water?), to think beyond humans as the dominant species, to go beyond government as the key regulating actor (to consider the influence of grassroots movements), to imagine “wild cities” as sources of multiple nature/s (to overcome both the human need to control things and to re-introduce wild urban natures such as eco-corridors and urban forests), to re-think humans fear of dirt (to “open the waste bins” as a treat for foxes and raccoons), and to re-value urban waterways as a source of nature. Rather than leave these fantastical possibilities as distant futures, the room also recognised that “we need to act in the next 12 years” to allow both humans and nonhumans to adapt to climate change. Strategies of action could include efforts to understand public perception, interdisciplinary collaborations, monitoring, and consideration of socio-cultural factors and their economic ramifications. Intended wildness such as explored by Hwang and Yue (2019) is one example where positive relationships could be created with urban nature.

As these frames are a recent contribution to conversations around the nature of cities, they are yet to be fully explored. However outstanding strings from the discussion included that:

- Cities must be considered holistically, including biologically, to satisfy aesthetic-sensory experiences, and for people to sense nature as part of ourselves.

- The frames of “wild, stray and care” are highly site-specific where geographic, climatic, socio-cultural conditions all have influence. Identifying the specificity of nature to that region (where even single weeds have a function) is crucial.

- Local expert knowledge in these regions should be acknowledged and integrated.

- Systemic and strategic integration is needed among wild, stray, care by each party. For example, designers could to focus on the housing of non-humans in the city to make them more favourable to humans while supporting flexibility and resourcefulness.

- To consider the nested scale and timescale of urban species and situations.

- It is imperative that a transdisciplinary approach that acknowledges disciplinary assumptions and boundaries to transcend them is supported. For example between managers, planners, designers, developers, residents, policymakers and researchers.

Indeed, such a transdisciplinary approach was tested in this seed session. From the rich conversation and stickies created, these frames provide some rich fodder in which to reassess natures place in the city and humans place within nature. The positive and energetic reception received is very encouraging for further conversations! We look forward to participating in a broader dialogue in the years to come.

Ferne Edwards, Amy Hahs, Yun Hye

Barcelona, Ballarat, Singapore

With thanks to all participants: Pippin Anderson, Méliné Baronian, Katherine Berthon, Nathalie Blanc, Lindsay Campbell, Elsa Caudron, Maud Chalmandrier, Marianne Cohen, Marguerite Culot, Samarth Das, Laurent Favia, Cathel de Lima Hutchinson, Chloé Duffaut, Grégoire Durand, Arthur Feinberg, Katie Holten, Juan Miguel Kanai, Aleksandr Kiyatkin, Nadezda Kiyatkin, Julia Lorenz, François Mancebo, Katherine Moseley, Seema Mundoli, Samuel Okello, Simon Pittman, Marisa Prefer, Hugo Rochard, Sylvie Salles, and Lu Yu.

Special thanks to our TNOC session scribe, Jenna Witzleben, and to co-convenor, Kevin Sloan, who was unable to make it on the day.

Reference:

Steele, W., Wiesel, I., and Maller, C. (2019) More-than-human cities: Where the wild things are, Geoforum, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.04.007.

about the writer

Amy Hahs

Dr Amy Hahs is an urban ecologist who is interested in understanding how urban landscapes impact local ecology, and how we can use this information to create better cities and towns for biodiversity and people. She is Director of Urban Ecology in Action, a newly established business working towards the development of green, healthy cities and towns, and the conservation of resilient ecological systems in areas where people live and work.

about the writer

Yun Hye HWANG

Yun Hye Hwang is an accredited landscape architect in Singapore, an Associate Professor in MLA and currently serves as the Programme Director for BLA. Her research speculates on emerging demands of landscapes in the Asian equatorial urban context by exploring sustainable landscape management, the multifunctional role of urban landscapes, and ecological design strategies for high-density Asian cities.

Leave a Reply