How can we speed things up? For scientists, if they are going to help make cities more sustainable, what research is critical to help city decision makers make decisions? I will go out on a limb and attempt to explain my views below. I will be pointed and do not mean to offend anyone, and know that I am speaking also about myself.

First, in terms of urban sustainability solutions, do we really need anymore “advancement of urban ecology theory or basic empirical research?” Do we not know enough NOW to create reasonable solutions to conserve urban biodiversity, water, energy, etc.? What more can we really learn? We continue to spend lots of resources (time and money) to perhaps further understand some ecological, social, or economic variable. For example, I am currently doing these basic ecology studies—for example, which migrant birds use urban forest patches as stopover sites.

But much of our research is reductionist science. In other words, studies are reduced to such simple parameters that we already know the broad outlines of answers before we start—of course migrant birds use urban forest patches! People may argue that we need multiple lines of evidence, especially if cities are going to spend time and money on a solution (for example, is conserving that 1 ha forest patch going to be used as a stopover site for birds?). Unfortunately, most science and scientific studies are geared towards reaching other scientists, not the general public or decision makers. We are speaking amongst ourselves. Thus, most research results stay in journals and have little impact on public policies or strategies.

I think we already know enough to craft reasonable design and management practices in urban areas. The unknown is how do we navigate the current political, cultural, economic, and public sectors and actually implement this knowledge in design. What we need is more research geared towards the “Science of Implementation”.

What does that mean and how can we forge a reasonable path forward?

First, scientists need to tailor their research so their outcomes are explicitly tied to what planners, policymakers, and other built environment professionals (e.g., civil engineers, landscape architects, etc.) actually need in order to create a design, a policy, or other initiative that actually moves the sustainability needle. Conventional development and design inertia is strong and it is not enough to make research data available to built environment professionals (usually published in a journal) and expect it to be implemented in the public arena.

This means that we need to determine where in the urban planning or design process is the best place for ecological and environmental data to be considered and discussed. And what data? Ecologists need to converse with local and regional built environment professionals to learn more about the design process and the critical steps (and constraints) that people make when creating a policy, planning strategy, or design. Further, if the outcomes from an ecological or social science study are going to be meaningful, they need to be in a format that is easily translated.

As an example from my work, in the course of working with planners and landscape architects on green development projects, several of them asked me, “Is there a biodiversity metric/tool that could be used to assess different development designs and their impact on biodiversity? If we had this, we could give feedback to developers and environmental consultants about how to improve their designs.”

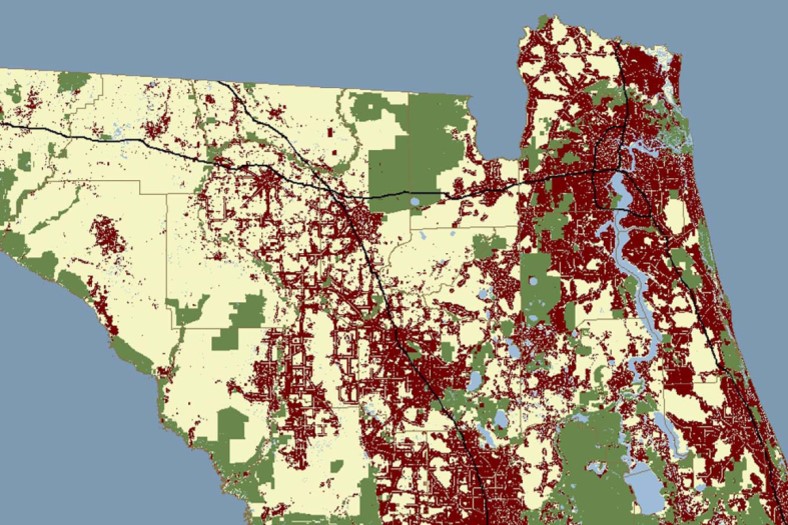

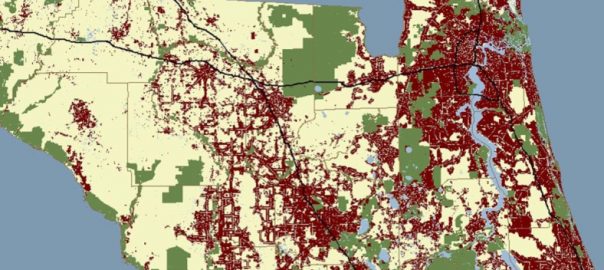

After listening to practitioners, I thought about their concerns for a while and decided that a synthesis of the literature was needed. I focused on birds. I knew there was lots of empirical research on birds, but it is buried in a number of different journals. What was needed was a synthesis of published research. So, we conducted a systematic review of known empirical research, and we determined which birds do and do not use urban landscapes. Using this synthesis as a backdrop, we developed an online tool where people could put in different landscape designs and get avian habitat scores. This research is published and the building for birds tool is available online. Land developers or city planners simply input the amount of trees and sizes of forest fragments conserved and the tool will output an avian habitat score for breeding and migrating birds. I worked with a number of planners and designers to make this tool transparent and as easy to use as possible.

The Building for Birds online tool has been out there for two years and is applicable to any city in North America. Is it being used? I did a speaking tour around the U.S. to market the tool and get feedback. Built environment professionals like it and so I was hoping people would use it to make planning and design decisions. Has it happened? Alas, very few cities and environmental consultants are using the online tool to make decisions.

So, what is going on? There are several possibilities. First, biodiversity conservation may be the lowest on the totem pole of urban sustainability issues. Energy, water, and even transportation seem to occupy higher considerations in city/county planning and have associated land development regulations (LDRs). However, there are very few regulations concerning optimum designs for conserving native plants and animals. Often, city planners primarily think of large patches and corridors as being important for biodiversity (particularly wildlife); save for generic conservation of open space across a city, often the small, unconnected forest fragments/natural areas and even large trees are not considered as important wildlife habitat. However, these small bits of habitat are important to a variety of birds, insects, and other animals.

Second, without policies that help guide and regulate biodiversity conservation, environmental consultants and developers are not keen to try something new (especially if they do not have to). Without policy directives, it takes a maverick team of built environment professionals to implement a unique design that accounts for biodiversity conservation. Unfortunately, these forward-looking individuals are few and far between. From my experience, the building for birds design tool is applicable to any situation but very few people are taking advantage of it across the U.S. This is a bit frustrating, as I thought if I made the tool simple enough and applicable to planning, folks would use it.

How do we improve implementation? Not an easy answer. We do need ecologists and other scientists collaborating more with planners, landscape architects, and other built environment professionals. Only by learning from each other can we tailor research that is useful in the planning and design process. My collaborations with these decision makers did produce a useful tool (albeit not as well used as I would have liked). I learned quite a bit about planning and what makes or break a development project. For example, for a developer (with a bank breathing down their neck) it is all about avoiding uncertainty. A developer will do a biodiversity design if it will help them get their development approved and can start construction right away. Research data will not be used in planning and/or design if it is not supported by policy. And to get a new policy passed, research data must be in a format that is transparent to policymakers so that they can easily craft a policy for land development regulation.

Thus, I am saying that as scientists we are conducting research in (sort of) a vacuum, more geared towards pleasing each other but with an outside hope that someday our data will be used in the “real world”. However, from my experiences, planning staff and regulators are loathe to require “x” (some sustainable policy or action) if there is not good data to back up the requirement. As I have stated before, data is typically buried in scattered journals and most practitioners do not have the time to scour the scientific literature to come up with a rationale for a policy. Perhaps one important step for scientists is to listen to what practitioners need and help conduct a systematic review of the literature (be it birds, other wildlife, water, energy, etc.). The output would be a scientific summary, (a one pager perhaps) for a planner to talk with elected officials in order to create a new policy. In turn, if done properly, this review could be published in an academic journal.

Even the most “transparent” data or tools can still be underutilized (such as the bird tool that I developed). In the academic world, political scientists, urban and regional planners, landscape architects, and social scientists need to become familiar with city/county decision making in order to understand the important “levers” in urban planning and design process. For example, low impact development features (e.g., rain gardens, permeable pavement, bioswales, etc.) are well known to help improve water quality in an urban development, but are underutilized. Why? It is difficult to say what are the reasons across the board because every city/county situation has local flavors and barriers to implementation. The challenges (and opportunities) are likely different from one area to the next. Probably, the most common barrier is just plain inertia. Environmental consultants, developers, and even city/county regulators are comfortable in doing a design/development in a certain way and any change is met with resistance.

To adopt a new way of doing things, social science researchers can conduct studies to determine what makes regulators, policymakers, environmental consultants, and even the public “tick”. If rain gardens are going to be prioritized, for example, what do regulators need in order to give, in this case, stormwater credit for a rain garden instead of conventional curb, gutter, and pond? Most likely they need synthesized data that states rain gardens work in their local area. Scientists know where to go to review this data and could provide that one-pager for decision makers.

In summary, natural resource scientists should collaborate more with practitioners and decision makers before they conduct research. The study and output data should be collected and presented in a way that is useful for practitioners and decision makers alike. To help decision makers overcome conventional inertia, social scientists need to measure how people operate and make decisions, determining the “leverage points” were ecological data could be inserted to sway decisions. Overall, we need to stop creating and writing scientific research for each other and make it more it explicitly available for city/county decision makers.

Mark Hostetler

Gainesville

Diane: Thanks for the article. It will take a bit to move the needle – but “on the ground” examples and practices will help to shift the norm.

Really enjoyed reading this article! Moving towards sustainable solution are really important and implementing in into urban life is something that needs to be talked about. I read another article similar to yours which was also educating on the topic, you might find it interesting: https://www.valuer.ai/blog/identifying-new-business-models-and-technologies-within-sdg-11

Hello Daniels: Thanks for your comment. A little reflection about theories, frameworks and terminology. For the most part, I think in the literature we spend way too much mental power on frameworks and theories, rehashing old ideas and packaging them in supposed “new ways.” One example – is “translational ecology” – a term that is just a new way of saying “Extension.” In other words, translating science into actionable practices and policies. It is my opinion that most of these frameworks and theories are baloney and still – researchers talking to researchers. While I think there may be a few decent models that help translate science to reach practitioners and the public, for the most part, they do not. I think each of us, based on available science, can come up with a top ten list of practices that could make a difference, – but how do we implement? Not another model for pete’s sake – but perhaps innovative collaborative science that “empirically” addresses the gaps, barriers, challenges, and solutions.

Great article Mark! I love the notion of a more rigorous science of implimentation. I’m wondering if there may be some relevant frameworks to embrace here such as Geels’ “Multilevel Perspective” on sustainability transitions or “Diffusion of Innovations” theory or Schon’s notion of “Reflective Practitioner”, or others? What I like about these is that they offer a way to understand how ideas either stagnate or succeed in relation to range of factors (governance, technical, communication/etc)