about the writer

Jessica Kavonic

Jess is part of ICLEI’s Cities Biodiversity Center as well as ICLEI Africa’s Resilience team. She has a background in atmospheric science with a more specialised knowledge of climate change and its relationship with a sustainable approach to development.

Introduction

I was standing in the street in the middle of Dar es Salaam. Every one of my senses was in overdrive as stimuli after stimuli overwhelmed me. Smells of plantain and corn being cooked on open fires. Traffic hooting and honking and people shouting and talking and laughing and running. I quickly move out the way as a donkey cart comes hurtling out of nowhere. A flash of colour as a woman wearing the most beautiful kanga almost bumps into me.

My colleague and city official grabs my arm and laughs. “You see how busy it is here. As more and more people come into the city this area gets busier and busier. But this area experiences flooding. How do we best deliver services to areas like this? How do we plan appropriately here when there is already so much going on?”

Searching for these answers keeps the ICLEI Africa team up at night. How does one support shifts in decision making and city planning to effectively allow future cities to deal with the rapid changes expected? How does one support cities to embrace and implement new ways of thinking and doing that can guide how society works? How can one help cities become solution- and action-orientated?

The Urban Natural Assets for Africa (UNA) programme is trying to answer some of these questions by implementing walking tours in multiple African cities. These walking tours are then combined with an urban tinkering approach in order to co-produce local participatory scenarios.

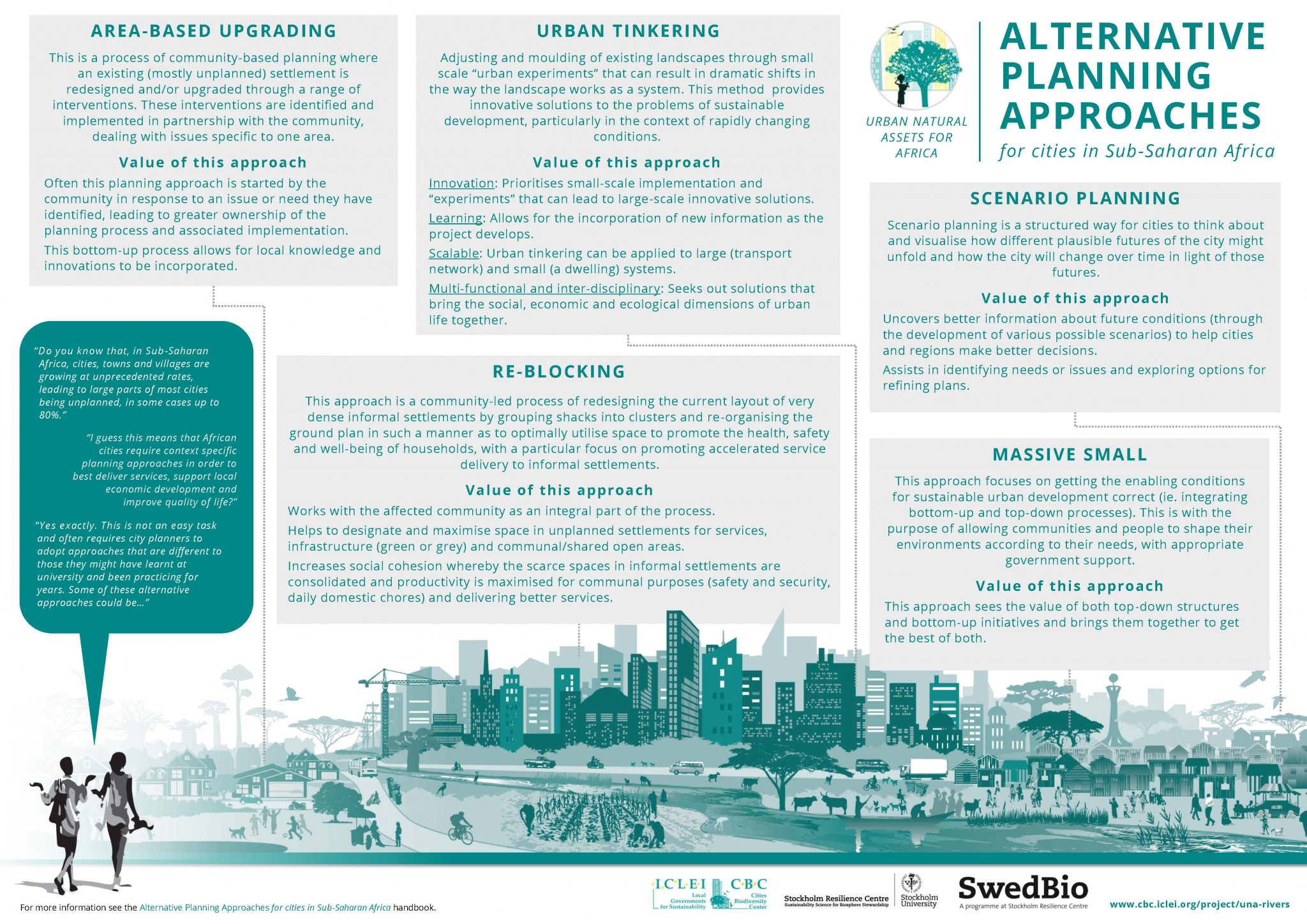

As expressed by the image above, urban tinkering is a socio-environmental theory that promotes small scale urbanism through adjusting and moulding the existing landscape through small-scale “experiments” that can result in dramatic shifts in the way the landscape works as a system. But does it hold the answer? Is it an appropriate method?

We asked a mix of scientists, practitioners and city officials who actively participated in the UNA walking tours to reflect on their own experience. Specifically, we asked: Why are we doing walking tours in African cities? What small actions made an impression on you? Why is urban tinkering an appropriate method?

There are many interesting and common threads in their responses. Those that stand out are:

- Small-scale interventions that are possible might add up to wider-scale impacts. The big systemic problems seem impossible to solve, especially when there are insufficient resources. We become paralyzed. Perhaps the big fix isn’t available (or even understood sufficiently to address the challenges), but a collection of small interventions can add up to a pervasive impact.

- Walking tours themselves are a beneficial collaboration mechanism, as they provide the space to effectively share knowledge, understand the local context, break down power dynamics and build relationships.

- Understanding the local context is imperative when designing future interventions and dealing with rapid change. Walking tours and an urban tinkering approach allow a group of diverse stakeholders to grapple with the real context in a hands-on and interactive fashion.

- There are already urban solutions being implemented at ground-level in many pockets of African cities. City officials should support and build on these opportunities.

- Urban tinkering provides the opportunity for decision makers and communities to collaborate in more effective ways.

- Decision makers are often overwhelmed by the thought of large-scale implementation. Especially coupled with limited budget and capacity for management and maintenance. Urban tinkering relieves city officials of this burden by providing an alternative planning and implementing approach that is better suited to their context and available resources.

- Despite being an approach that focuses on small scale urbanism, the opportunity for up and out-scaling is large. Urban tinkering allows for a “safe-to-fail” approach, which allows for the discovery of innovative approaches that if tested at scale might be too complex. If successful they can then be used to explore ways for larger transformative interventions.

From the responses it is very clear that all authors are suggesting that we need to do more of this in cities everywhere. We need to get people out of their offices and shift the focus away from the operational day-to-day grind. We need to really talk to each other. More importantly we need to get people talking to communities that USE the areas of the city. That changes the dynamic. It produces new ideas that wouldn’t have been possible. It gets the mind, heart, and blood flowing.

https://youtu.be/gZ7i-lplHsQ

Video by Viveca Mellegård.

about the writer

Odhiambo Ken K'oyooh

Odhiambo Ken K’oyooh is currently the Director in charge of Environment (Conservation and Stewardship) in County Government of Kisumu (which forms part of the Department of Water, Climate Change, Environment and Natural Resources).

Odhiambo Ken K’oyooh

The peer learning sessions—whereby all the different stakeholders shared success stories—made a great impact on me, changing the way I view urbanization challenges.

In the case of Kisumu City, a fast growing lakeside city in Kenya, we did a walking tour to identify the challenges along River Auji. The river is an important natural asset snaking through two important informal settlements of Manyatta (on the upper reaches) and Nyalenda (on the lower reaches). Siltation, and degenerated aesthetics characterized the stretch toured. The walking tour however also identified the opportunities to address the observed challenges.

What small actions made an impression on me?

The peer learning sessions—whereby all the different stakeholders shared success stories—made a great impact on me, changing the way I view urbanization challenges. Deep community participation approaches and learning appear to be the key element for the successful implementation of projects.

In addition, the practical action of walking, making stops and exploring opportunities at certain stop overs made the practical beat of our urban tinkering session a lot more sensible in coming up with appropriate solutions to challenges faced along River Auji.

Why is urban tinkering an appropriate method?

Theoretical aspects of urban tinkering well prepare the participants with what to expect. It lays the foundation on importance and the important aspects of developing solutions. While on the other hand, field tours bring out the practical aspects of this methodology. Practitioners, representatives’ from city authority and locals are able to freely share experiences and find practical solutions to observed challenges during urban tinkering approaches.

In the case of Kisumu City, the method enabled the team to identify appropriate measures to deal with the challenges faced by communities settled within the lower reaches of River Auji. Silt traps in certain locations, along the river course, appeared to be a preferred sustainable solution to control the river siltation on the lower reaches. Woodlots and greening complete with resting benches was preferred, as a way of improving aesthetics, within a government school bordering the river. A bridge to improve safety for school children was also proposed by community members. This is meant to help pupils’ crossing the river on their way to school, as a remedy to reduce the risk of drowning in the river during high flow periods. It is worth-noting that the aforementioned was only made possible through the participatory nature of the tinkering processes.

about the writer

Aiuba Oliveira

Aiuba is currently an advisor to the President of the Nacala Municipal Council (Mozambique) in the areas of Territorial Planning, Urbanization and Development Projects.

Aiuba Oliveira

The ideas we exchanged as we walked became increasingly interesting. Now we look at our city differently and as we walk we think about the small changes we can make, making our city better in small steps.

Then we were informed that the goal was to walk around the community and talk about how we could overcome the challenges we face in our city using the method called “Urban Tinkering”.

The idea aroused great interest in me because our city faces major challenges such as erosion that drags soil to our port, lack of drainage, poor access to clean water, decent housing, sanitation, and more. They are beyond local financial capacity and it is not easy to get money from the national government or other donors.

But while the challenges are great, we were asked that while we were walking we should think of small scale things that could help overcome the challenge and perhaps offer other opportunities, environmentally, socially, or economically.

The idea was interesting and made me start thinking differently about the need for big budgets to overcome the challenges we face in the city.

Before leaving, we examined alternative planning methods and how we can embrace informality and use what we already have in our city.

As we walked a little farther, we came to an area that was once a park, a place for children to play safely and where people from the community used to meet to talk. But now there were few trees and the play area was broken. While we were in the park under a tree, we talked about how if we started fixing the park, planting more trees and grass, fixing the swings and play area, then the kids would have a safe place to play again and we could stop the sand from being eroded into our port. Over time, when we received more money, we could improve the park more.

It was hard not to dream big, and instead to think about what we could do with smaller ideas to overcome the challenge. But we soon realized that we had enough to already solve part of the problem and provide other benefits.

We were told to talk and get involved with community members as we walked, to find out what they needed or how what ideas they had. We are not used to just talking to people about street work; we usually gather in a meeting lounge to discuss matters.

We walked a little further and found a building, which had a great view of the bay, with a large and beautiful free ground in front. But the building was in a very poor state. The ground floor was abandoned and full of rubbish. The residents pour dirty water from the balconies to the ground. The front had scruffy bushes. As we passed the building, under the blazing sun, we talked: what if we began to requalify the building, clear the ground floor, and put in some income-generating activities to ensure maintenance? We could clean the front yard and put in shade trees and seating benches for people to sit and watch the sunset in Nacala Bay.

These actions would not really require much money, but would make the place one of the most appreciable in the city because it has incredible views of the bay and this would have a good impact on city life.

The ideas we were exchanging became increasingly interesting. Now we look at our city differently and as we walk now we think about the small changes we can make.

about the writer

Viveca Mellegård

Viveca is a researcher and filmmaker. At the BBC she directed and produced long form science, history, and arts programmes. For the past five years she has integrated film and photography as methods in sustainability projects aiming to build better cities, to know more about human-nature interactions and to include marginalised or unheard voices.

Viveca Mellegård

We walk in African cities to put ourselves at the edge of knowledge and experience. It is a blurred boundary where ideas begin, where they reformulate and reshape, where they fill in at the point at which reality stops.

My pace slows down and gradually my ears attune to the layers of sound mixing and meandering in and out of each other. Our group stands next to a bridge over the Auji river and behind the voices discussing flooding, waste dumping and contaminated water, the stream gurgles over what looks like the remnants of a t-shirt caught by stones on the river bed. I begin to notice details that my eyes had overlooked. Tiny striations on leaves, an insect crawling deeper into the magenta belly of a flower.

Poet and forester, Gary Snyder, promotes this kind of perception with the body, the conversation between ourselves and our environments as “The way to see the world: in our own bodies”. Walking can make all of our senses come alive. A one-dimensional interaction becomes five dimensional. We stop for a moment and our ears attune to the layers of sound all around us. Our eyes pull focus between small details and the big picture. Our sense of smell picks up nuances and changes in scent. We touch and feel different textures, we might taste something.

Urban tinkering can be a way to bring about a whole person engagement with ourselves, others and a particular place because we enter into an activity that asks us to observe, listen, respond, inquire, be curious. In my view, when we walk together in African cities with a tinkering mindset, with the intention to understand more, several possibilities emerge for transformations within ourselves as individuals, between ourselves and others, and between ourselves and the urban landscape.

The first is connection. We connect with each other by communicating what we see and comparing our points of view and understandings of what we observe. There is also a connection to the places we walk through. We mingle with a place and it mingles with us.

The second is cooperation. With a shared purpose to tinker so that we can live in more climate resilient cities, our different experiences, skills and types of knowledge have the potential to become the material from which we shape a shared vision. In nature-based urban tinkering, nature is our partner in guiding and suggesting smart and simple solutions.

Thirdly there is creativity. We bounce ideas off each other, become inspired by what we see, hear, touch, taste, and smell. Walking and moving through space, memories become dislodged and a creative flow begins. Perhaps it is the kind of potent force that can loosen the grip of fear, paralysis even and the feelings of helplessness when confronted by the scale and complexity of problems. (See psychologist R.J Clifton on the human response to catastrophe, in Kimmerer, 2013).

Then there is caring. After spending time somewhere, we become entangled with it and even in our over-stimulated mental landscapes, we find that images have been carved into our memory, our thoughts, and in our bodies. People make an impression on us, we make an impression on them. We are changed by a place and a place can be changed by us. Reciprocal exchanges might sometimes be invisible to the eye but in our imagination, the possibilities for how a city could or might be, has the charge of a creative spark.

Walking and urban tinkering complement each other by creating the conditions for a creative and collaborative mindset—the kind of mindset from which solutions that can lead to more climate resilience and equitable cities might emerge.

We walk in African cities to put ourselves at the edge of knowledge and experience. It is a blurred boundary where ideas begin, where they reformulate and reshape, where they fill in at the point at which reality stops.

Reference

Kimmerer, R.W., 2013. Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Milkweed Editions.

about the writer

Ellika Hermansson Torok

Ellika Hermansson Török is a Senior Adviser for SwedBio at Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, and is responsible for SwedBio’s project portfolio of urban collaborative projects in developing countries.

Ellika Hermansson Török

Multi-actor action planning—informed and inspired by the urban landscape

Urban tinkering functions by promoting a diversity of small-scale urban experiments that, in aggregate, can lead to large-scale, often playful innovative solutions to the problems of sustainable development.

Over the years, I have enjoyed many field trips at conferences and workshops. These often showcase practical examples related to the conference themes, and can provide valuable insights and new knowledge. But unlike walking workshops, field trips are seldom designed to actively advance the discussions or workshop processes. After having experienced the walking workshop in Kisumu, Kenya, I think of some of these previous field trips as “lost opportunities”.

I am working for the SwedBio programme at Stockholm Resilience Centre, a programme that devotes a lot of time and resources into facilitating dialogue on different scales between different actors that represent different knowledge systems such as research, policy and practice, including traditional and indigenous knowledge. Walking workshops have been used by some colleagues in close collaboration with our partner organisations in developing countries, but the walking workshop in Kisumu was the first time for me.

Some quick impressions and reflections: why are we doing these tours, and why urban tinkering?

Understanding.Research has shown that walking stimulates creativity, and it is well-known that learning processes can be improved by using multiple senses. When walking in pairs along the Auji River in Kisumu, we got to use all our senses when observing, identifying, discussing and analyzing problems and possible tinkered solutions. I am pretty sure this “physical experience of observations” helped the diverse group of participants—with very different backgrounds, expertise and language—to both better understand the challenges and opportunities, individually and mutually, and to generate more informed and creative ideas for solutions than in a more formal workshop setting.

Sharing.Insights from previous walking workshops also suggest that discussions that take place in the landscape encourages practitioners and community members to actively share their experience-based knowledge. It creates synergies and innovations based on connections across knowledge systems, rooted in equity and reciprocity. Meeting outside the conference venue, in a local landscape guided by local community members or other local actors, helps to level the power within a group.

Engagement.Like everyone else at the workshop, I was aware of the widespread and severe problems of flooding. But watching local school kids play outside their school building, visibly stained by previous flooding events, made it clear to me and other participants the impact flooding has on the community. This observation effectively brought the reality of local communities into the discussions and injected energy into finding possible solutions. In my mind, engagement is necessary for creating long-term commitment and behavior change.

Prioritisation. The participants were instructed to take photographs of both problems and ideas for solutions identified during the walk. They did so using a method called Photovoice, which is often used for community-based participatory research to document and reflect reality. The photos taken by the participants, with explanatory captions, were helped with the prioritisation discussion. They helped us remember what we had observed and discussed during the walk, and they made the prioritisation process more informed and concrete.

Nothing is useless. By using the urban tinkering approach (Elmqvist et al. 2018), characterized by, for example, “build on what you have on the ground”, “integrate built systems with living systems”, and “see informality as an opportunity for innovation”, participants came up with a plethora of nature-based solutions for decreasing future flooding of the above-mentioned school.

As suggested by Elmqvist and colleagues, urban tinkering is most useful and easily applied in rapidly urbanizing regions of developing countries, harnessing social and human capital for innovation. It functions by promoting a diversity of small-scale urban experiments that, in aggregate, can lead to large-scale, often playful innovative solutions to the problems of sustainable development.

The results from the application of the concept through the walking workshop in Kisumu are promising, and with financial support by SwedBio some of the ideas will be implemented. There is a lot that can be done with very limited resources, as long as there is creativity.

Reference:

Thomas Elmqvist; Jose Siri; Erik Andersson; Pippin Anderson; Xuemei Bai; P.K. Das; Tatu Gatere; Andrew Gonzales; Julie Goodness; Steven N. Handel; Ellika Hermansson Török; Jessica Kavonic; Jakub Kronenberg; Elisabet Lindgren; David Maddox; Raymond Maher; Cheik Mbow; Timon McPhearson; Joe Mulligan; Guy Nordenson; Meggan Spires; Ulrika Stenkula; Kazuhiko Takeuchi; Coleen Vogel. 2018. “Urban Tinkering”. Sustainability Science. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11625-018-0611-0

about the writer

Pippin Anderson

Pippin Anderson, a lecturer at the University of Cape Town, is an African urban ecologist who enjoys the untidiness of cities where society and nature must thrive together. FULL BIO

Pippin Anderson

To take a diverse bunch of people from different backgrounds, work place, and life experiences and put them in a shared space is a very unifying thing to do. At once we are all on the same page, faced with the same scenery, evidence and circumstance.

And what better way to tackle a problem than to walk through it? I had the pleasure of joining one of ICLEI Africa’s walking workshops in Kisumu in Kenya recently and was struck by the tremendous value of walking to problem solving. Here I got to be part of an urban tinkering workshop which sought solutions towards improving the state of a local river. The workshop spanned three days and involved city officials, people from state government, local academics, and academics from elsewhere. In addition to the individual benefits of improved thinking capacity and rhythms that allow our own thoughts and voices to bubble up, the collective walking proved to be very useful too. To take a diverse bunch of people from different backgrounds, work place, and life experiences and put them in a shared space is a very unifying thing to do. At once we are all “on the same page”, faced with the same scenery, evidence and circumstance. We are all feeling the heat of the day, stepping over the same discarded banana peels and plastic bags, and all smelling and hearing the river in front of us. This immediately brings everyone together through shared understandings and experiences. Locals could provide insights to questions from new comers, and ideas and solutions, their likely successes and short-comings could be discussed in situ.

In his article on the benefits of walking (New Yorker, 2014), Jabr gives us a quote from writer Virginia Woolf, who describing her great pleasure in walking around London, talks of the joy of being, “right in the centre and swim of things”. This is very true. A walk through any city will put you at the heart of its people, their energy, their joys, and their sadness. You will see what they eat, what they wear, and how they spend their time. You will be at the very “swim of things”. This proved very true of our walking workshop. The energy and collective understanding on returning to our workshop space to start designing solutions was palpable.

And why tinker? Tinkering—seeking out those small opportunities for change and influence—is a very appropriate approach in an urban, fiscally-constrained environment. The spaces around rivers in cities in Africa tend to be heavily occupied and well used spaces. In this particular circumstance a light touch with clever, initially small, wins is the order of the day. Tinkering, which tends to towards the considered, out-of-the-box thinking, novel interventions and solutions, builds on past transactions, and seeks where possible to running with current energies, is just the right approach to these collaborative urban environmental engagements.

about the writer

Celestine Collins

Celestine Collins is the Director of Education, City of Kisumu (Kenya). She holds a Master of Education Degree. She is currently acting as the Assistant City Manager as an additional responsibility and the Focal Point for Disaster Risk Reduction with the United Nations for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR).

Celestine Collins

Through engagement, we realized that small actions could actually make a big difference.

Cities are currently experiencing adverse environmental challenges due to climate change, and the degree to which they need to cope with and adapt to such challenges continues to increase. Kisumu, as is the case with other cities, has been experiencing rapid urbanization, accompanied by an increase in environmental challenges that accelerate vulnerabilities. Realizing the need for deliberate action, the office of the City Manager (City of Kisumu) is committed to strengthening the capacity of the City (as an institution) towards resilience. It is for this reason that we as a city have identified our challenges and seek to address them for a more sustainable and resilient city. As a result, we have joined the UNA programme, which has been designed to support local governments in Africa successfully integrate nature-based solutions into land use planning and decision making processes. We embrace and plan to work together for a better course and embrace the Urban Tinkering approach, with the help of ICLEI Africa and are committed to achieving our desired goals.

The challenge we face as an institution is lack of capacity to effectively address issues that adversely affect the people and the institution as a whole, such as majorly floods and solid waste. It is for this reason that I feel that small scale urbanism should be given the attention it deserves. There is a need for institutional capacity building to support local governments with this approach. Local governments are the closest level to the citizens and communities and therefore have a responsibility to take a lead in responding to crises and emergencies and to ensure essential services to citizens (water, health, education, transport, etc.) are resilient to disasters.

Due to rapid urbanisation, population growth, increasing demands for effective service delivery, and infrastructure development and improvement on the City Management of Kisumu, there is immense pressure to deliver. This puts the City in the forefront of the agenda. In the week of 19-23 August 2019, Kisumu hosted the first ever Walking Workshop in their history. It gave the participants a direct view of the challenges we face as a City. This was so exciting as it moved away from the normal dialogue approach that most of the time does not actually give the true picture of the situation at hand.

Through engagement, we realized that small actions could actually make a big difference. A small action that made an impression on me was the fact that the community can be actively engaged in taking responsibilityfor the good of their environment. With a little empowerment, capacity building and monitoring, the City can reclaim its glory and move forward towards resilience. It is important to note that to achieve the best results we need multi-stakeholder engagement, instilling in people a sense of belonging and ownership.

about the writer

Julie Goodness

Julie Goodness has a PhD in Sustainability Science from the Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University; her research is focused on urban social-ecological systems, functional traits and ecosystem services, environmental education, design-thinking and design-based learning, social action and community development.

Julie Goodness

The walking workshop format seems to help to level power issues and allows more voices to be heard. During the walk, I observed people talking that had been largely silent when we were previously in an inside meeting room.

I observed that the walking workshop allowed us to have a special kind of grounded discussion, because we weren’t in a closed, inside meeting space; instead we were actually out there in the environment in which we wanted to create positive change. The abstract suddenly became concrete, and we could take in and share experiences with all of our senses. This created a particular kind of understanding, empathy, and common knowledge among participants. It allowed us to reach a shared consensus on river issues, so that we could move towards thinking about potential solutions.

One thing that made a particular impression on me was how the walking workshop format seems to help to level power issues and allows more voices to be heard. When we were out in the field, doing the river walk, I observed people talking that had been largely silent when we were previously in an inside meeting room space. The people who were now talking more and speaking up were often the residents of that community (which is a crucial group to include and integrate insights from in any urban planning project). It seemed that suddenly being in their home environment enabled them to share their knowledge (i.e., they became the experts), and we could all talk about what we were seeing in the landscape together.

Another thing that made an impression on me was the experience of using a photovoice method during the walking workshop as an additional way to identify challenges and facilitate discussion. Photovoice is a method that invites participants in a project to take photographs as a way of telling their own stories through images that represent their perspective at a particular moment in time. Participants paired up during the walking workshop to take photos together. After the workshop, paired participants selected their most important photos and gave them captions that described the challenges the images depicted. Participants then used the captioned photos as objects for discussion, and this process eventually allowed participants to reach agreement about the most important issues to prioritize for action along the river. I think the photovoice was a useful activity to guide participants through this prioritization process.

From the winnowing of ideas, participants decided work on a section of the Auji River alongside a school, which frequently floods and prevents the students from being able to attend their classes. The participants would like to create a nature-based engineering solution that uses vegetation to help reduce flooding impacts. They would also like to involve the schoolchildren in the vegetation planting process and maintenance, and include environmental education as part of the project. This is an urban tinkering initiative that the workshop stakeholders will strive to implement in conjunction with ICLEI during the next year.

Overall, I think urban tinkering is an appropriate method because it allows the implementation of positive action at any scale. While in many cases large amounts of human or monetary capital may not be available to create widespread changes across an urban area (particularly in under-resourced cities), urban tinkering can provide a way to utilize means available, test interventions, and provide learnings and seeds for future change that can be scaled up or out across new locations.

about the writer

Benard Ojwang

Benard Ojwang is the current Ag. Director for Environment at the City of Kisumu (Kenya). Benard holds a MSc in Urban Environmental planning and management, a BSc in Environmental Health and a Diploma in Environmental Resource Management.

Benard Ojwang

If we embrace the tinkering concept it will focus on local manifestation of such approaches wherein actors from across society create joint experiments to achieve common goals.

In the context of cities, green and blue infrastructure is to be understood as natural and semi-natural elements, like hedgerows, parks, ponds, or water courses. Together they form a green-blue infrastructure which is an important component of the urban tinkering approach. Experimenting with different combinations of these natural elements and the human-engineered “grey” infrastructure to provide social, economic, and environmental values to a city and its surroundings is an important part of the solution.

Urban tinkering can function by promoting a diversity of small-scale urban experiments that, in aggregate, lead to large-scale often playful innovative solutions to the problems of sustainable development.

Small interventions—”tinkering”—can serve to make urban features more accessible and potentially more equitable (i.e., just). Indeed, such acts can expand the sense of ownership among the community members, and belonging and allow for the kind of civic partnerships that can be useful in managing cities, particularly those that face fiscal constraints.

An urban tinkering walking workshop that has recently occurred in Kisumu (as part of the UNA programme) was radical in that while it sought to grow local conservators to lead and manage conservation spaces, it was always with a view to improving local social engagement in conservation practice and spaces.

The walking workshop adopted a variety of reflective and reflexive practices, including listening to communities, hearing their stories, including their views and visions for green space in their communities in our discussions and involving them in planning and management strategies. Conservators were also encouraged to form their own communities of practice where they could share and reflect on failures and successes.

The concept of urban tinkering was first introduced in Kisumu by ICLEI Africa to help the city manage its urban natural resources and promote biodiversity conservation. This has helped the city to plan effectively for the protection of our resources so that we can build better resilience (through managing the natural buffer zones).

As City of Kisumu, we plan for biodiversity, rivers, and lakes within Kisumu city through:

- Afforestation programmes, both national and local (tree planting in forests, catchment areas, schools, (wood lots) public institutions and open spaces.

- Desilting of river channels to mitigate flooding.

- Involvement of community in planning, management, conservation and protection of biodiversity and rivers.

- Improving of research to inform planning, policies and programmes.

- Continuous awareness and sensitization programmes.

- Setting aside adequate resources for planning and mainstreaming for biodiversity and rivers.

- Lobbying city and county leadership and County Assembly to consistently provide adequate resources for biodiversity and rivers.

Rivers are vital elements in the water cycle‚ acting as drainage channels for surface water. Most areas in Kisumu County are confronted with blocked drainages and bushy rivers leading to high rates of flooding and waterborne diseases.

Auji River was built by the World Bank in the early 1980s, but lack of maintenance has led to its current state: bushy shrubs‚ raw affluent discharge and soil chunks on its bed. It flows through Migosi ward‚ Manyatta B ward‚ Nyalenda A, and Nyalenda B wards.

Through the “tinkering walk”, we observed the following:

- Sewer pipe constructed across the river at fly-over hindering the flow of water.

- Continuous bursting of the old sewer pipe.

- Emptying of sewer by exhausters in the river therefore causing contamination.

- Farming activities along the river.

- Solid wastes like bottles and syringes deposited along the river thus interfering with the flow.

Therefore, if we embrace the tinkering concept it will focus on local manifestation of such approaches wherein actors from across society create joint experiments to achieve common goals.

Reference:

Thomas Elmqvist; Jose Siri; Erik Andersson; Pippin Anderson; Xuemei Bai; P.K. Das; Tatu Gatere; Andrew Gonzales; Julie Goodness; Steven N. Handel; Ellika Hermansson Török; Jessica Kavonic; Jakub Kronenberg; Elisabet Lindgren; David Maddox; Raymond Maher; Cheik Mbow; Timon McPhearson; Joe Mulligan; Guy Nordenson; Meggan Spires; Ulrika Stenkula; Kazuhiko Takeuchi; Coleen Vogel. 2018. “Urban Tinkering”. Sustainability Science. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11625-018-0611-0

about the writer

Thandeka Tshabalala

Thandeka Tshabalala is a professional officer in the Climate Change, Energy and Resilience work stream at ICLEI Africa. At ICLEI she is involved in implementing the Urban-LEDS II, Urban Natural Assets: Rivers for Life (UNA Rivers) and Reflecting Cities projects.

Thandeka Tshabalala

The exchange of knowledge between stakeholders can improve governance, ultimately leading to long-term and sustainable interventions.

The exchange of diverse views during walking tours builds relations amongst stakeholders. This allows for shifts of power dynamic that can potentially remove barriers to effective public participation and interdepartmental collaboration. Given the complexity of urban challenges in African cities, sustainable interventions that rely on local knowledge are vital for creating targeted and responsive interventions that improve people’s day to day needs. The walking tours implemented by the UNA programme saw decision-makers and “experts” being taken on a tour by community representatives and users of the open public spaces. This provided the opportunity for local residents to explain their context (problems and opportunities) firstand, allowing attendees an opportunity to see things through the community representatives’ eyes. The “experts” learned.

What experiences made an impression?

During a second walking workshop (implemented in Kisumu, Kenya), I was particularly impressed by a community member who took the lead of the tour with pride. He showed off some improvements he was doing, such as planting a nursery along the river banks, which not only has potential for future income for his family but also protects the river banks from erosion. As part of the feedback after the Kisumu walking tour one of the municipal officials said she found the tour useful because “it forced her to be out of her office and to walk a site that she has never walked before”. As a result, the walking tour gave her a different perspective on how she could use her expertise and knowledge to enhance some of the activities that the community members valued, and were already doing. The session also offered an opportunity for city officials from various departments to understand how vital interdepartmental and intersectoral collaboration is in tackling certain issues. This showed me how the exchange of knowledge between stakeholders can improve governance, ultimately leading to long-term and sustainable interventions.

Is urban tinkering an appropriate method?

Urban tinkering allows decision-makers and communities to look at challenges and collaborate in innovative ways. It improves the understanding of the local context by providng the opportunity to observe how people use an actual site and analyse how existing opportunities can be harnessed. This includes understanding what kind of economic or social benefits are derived from the site. The methodology focuses on small scale solutions and local knowledge that can later be upscaled to respond to everyday challenges.

about the writer

Semakula Samson

Semakula Samson is an agricultural officer and environmental inspector for the Entebbe Municipal Council (Wakiso District), Uganda. Sam is the focal point for the Urban Natural Assets for Africa programme.

Semakula Samson

Urban tinkering is definitely worth trying out in our developing cities as it gives opportunity for small scale innovations which, when aggregated together, can result into large scale worldwide environmental solutions.

Walking tours make it possible for us city managers to clearly come in touch with the issue at hand at the ground level, and as such enable us to come out with workable and sustainable environmental solutions.

During walking tours in the city you go on an excursion of you own city, like a tourist in a forest. Things that have become the ordinary for the local inhabitants begin to strike you and catch your sight. For example, you see the dirty stagnant water, mosquito larvae, think of the diseases that come with them. So, it is basically re-discovering the city.

It is correct to say that all cities are urbanizing, but they are all urbanizing slightly differently, owing to their localized opportunities and challenges. The spaces are urbanizing differently at the end of the day. Such small-scale difference are made apparent by city walking tours. After touring the city by walking you can then draw a conclusive picture of the city.

What small actions made an impression on me? Why is urban tinkering an appropriate method?

During the walk I was impressed by how well we all (city officials and members of the community) shared our vision of the problem in an area that has been hostile to other enforcement agencies. We are trying to develop a buffer between the wetland body and developments.

Urban Tinkering (UT), if well conducted, has the potential and energy to substantially aid conventional planning and development. UT allows for greater levels of flexibility and this complements finding multifunctional designs that can promote diversity, hence making it more likely to approach the unique challenges of urbanization in our cities. This results in greater levels of adaptability in planning. This is especially the case in our African setting, where development usually overtakes planning processes.

It contributes to the realization of Sustainable Development Goal number 11 (SDG 11) and the New Urban Agenda. It brings about a different mode of operation that brings together planning and management processes onto a similar platform and transforms the use of existing urban systems by helping design innovative simple and practical ways that expand their capabilities and functions. This enhances environmental adaptability to better meet the demands of the city.

UT is definitely worth trying out in our developing cities as it gives opportunity for small scale innovations which, when aggregated together, can result into large scale worldwide environmental solutions. UT also has close relation with improved systems approaches as it is a highly appreciated method which is critical to sustainable development.

It is hence worthwhile to undertaking UT as it creates a platform for interaction between the various environmentalists, planners, engineers, public health teams, and others city stakeholders. UT also works just as well in the peri-urban centre of our cities and this is where environmental challenges are best manifested.

Leave a Reply